Rules of Engagement: Performance and Identity in the War on Terror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generation Kill and the New Screen Combat Magdalena Yüksel and Colleen Kennedy-Karpat

15 Generation Kill and the New Screen Combat Magdalena Yüksel and Colleen Kennedy-Karpat No one could accuse the American cultural industries of giving the Iraq War the silent treatment. Between the 24-hour news cycle and fictionalized enter- tainment, war narratives have played a significant and evolving role in the media landscape since the declaration of war in 2003. Iraq War films, on the whole, have failed to impress audiences and critics, with notable exceptions like Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2008), which won the Oscar for Best Picture, and her follow-up Zero Dark Thirty (2012), which tripled its budget in worldwide box office intake.1 Television, however, has fared better as a vehicle for profitable, war-inspired entertainment, which is perhaps best exemplified by the nine seasons of Fox’s 24 (2001–2010). Situated squarely between these two formats lies the television miniseries, combining seriality with the closed narrative of feature filmmaking to bring to the small screen— and, probably more significantly, to the DVD market—a time-limited story that cultivates a broader and deeper narrative development than a single film, yet maintains a coherent thematic and creative agenda. As a pioneer in both the miniseries format and the more nebulous category of quality television, HBO has taken fresh approaches to representing combat as it unfolds in the twenty-first century.2 These innovations build on yet also depart from the precedent set by Band of Brothers (2001), Steven Spielberg’s WWII project that established HBO’s interest in war-themed miniseries, and the subsequent companion project, The Pacific (2010).3 Stylistically, both Band of Brothers and The Pacific depict WWII combat in ways that recall Spielberg’s blockbuster Saving Private Ryan (1998). -

Why Every Show Needs to Be More Like the Wire (“Not Just the Facts, Ma’Am”)

DIALOGUE WHY EVERY SHOW NEEDS TO BE MORE LIKE THE WIRE (“NOT JUST THE FACTS, MA’AM”) NEIL LANDAU University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) The Wire (HBO, 2002-2008) upends the traditional po- ed the cop-drama universe. It was a pioneering season-long lice procedural by moving past basic plot points and “twists” procedural. Here are my top 10 reasons why Every Show in the case, diving deep into the lives of both the cops and Needs to Be More Like The Wire. the criminals they pursue. It comments on today’s America, employing characters who defy stereotype. In the words of — creator David Simon: 1. “THIS AMERICA, MAN” The grand theme here is nothing less than a nation- al existentialism: It is a police story set amid the As David Simon explains: dysfunction and indifference of an urban depart- ment—one that has failed to come to terms with In the first story arc, the episodes begin what the permanent nature of urban drug culture, one would seem to be the straightforward, albeit pro- in which thinking cops, and thinking street players, tracted, pursuit of a violent drug crew that controls must make their way independent of simple expla- a high-rise housing project. But within a brief span nations (Simon 2000: 2). of time, the officers who undertake the pursuit are forced to acknowledge truths about their de- Given the current political climate in the US and interna- partment, their role, the drug war and the city as tionally, it is timely to revisit the The Wire and how it expand- a whole. -

The Wire the Complete Guide

The Wire The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 29 Jan 2013 02:03:03 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 The Wire 1 David Simon 24 Writers and directors 36 Awards and nominations 38 Seasons and episodes 42 List of The Wire episodes 42 Season 1 46 Season 2 54 Season 3 61 Season 4 70 Season 5 79 Characters 86 List of The Wire characters 86 Police 95 Police of The Wire 95 Jimmy McNulty 118 Kima Greggs 124 Bunk Moreland 128 Lester Freamon 131 Herc Hauk 135 Roland Pryzbylewski 138 Ellis Carver 141 Leander Sydnor 145 Beadie Russell 147 Cedric Daniels 150 William Rawls 156 Ervin Burrell 160 Stanislaus Valchek 165 Jay Landsman 168 Law enforcement 172 Law enforcement characters of The Wire 172 Rhonda Pearlman 178 Maurice Levy 181 Street-level characters 184 Street-level characters of The Wire 184 Omar Little 190 Bubbles 196 Dennis "Cutty" Wise 199 Stringer Bell 202 Avon Barksdale 206 Marlo Stanfield 212 Proposition Joe 218 Spiros Vondas 222 The Greek 224 Chris Partlow 226 Snoop (The Wire) 230 Wee-Bey Brice 232 Bodie Broadus 235 Poot Carr 239 D'Angelo Barksdale 242 Cheese Wagstaff 245 Wallace 247 Docks 249 Characters from the docks of The Wire 249 Frank Sobotka 254 Nick Sobotka 256 Ziggy Sobotka 258 Sergei Malatov 261 Politicians 263 Politicians of The Wire 263 Tommy Carcetti 271 Clarence Royce 275 Clay Davis 279 Norman Wilson 282 School 284 School system of The Wire 284 Howard "Bunny" Colvin 290 Michael Lee 293 Duquan "Dukie" Weems 296 Namond Brice 298 Randy Wagstaff 301 Journalists 304 Journalists of The Wire 304 Augustus Haynes 309 Scott Templeton 312 Alma Gutierrez 315 Miscellany 317 And All the Pieces Matter — Five Years of Music from The Wire 317 References Article Sources and Contributors 320 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 324 Article Licenses License 325 1 Overview The Wire The Wire Second season intertitle Genre Crime drama Format Serial drama Created by David Simon Starring Dominic West John Doman Idris Elba Frankie Faison Larry Gilliard, Jr. -

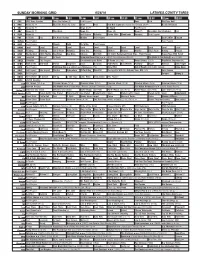

Sunday Morning Grid 6/26/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/26/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid Red Bull Signature Series From Detroit. (N) Å Beach Volleyball 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Incredible Dog Challenge Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Earth 2050 FabLab 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Happy Yoga With Sarah 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. (PG-13) The World Is Not Enough ›› (1999) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Un recuerdo para Rubé Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Firehouse Dog ›› (2007) Josh Hutcherson. -

The Son of No One

ANCHOR BAY FILMS AND MILLENNIUM FILMS PRESENTS A NU IMAGE PRODUCTION A FILM BY DITO MONTEL The Son of No One STARRING: CHANNING TATUM TRACY MORGAN KATIE HOLMES RAY LIOTTA WITH JULIETTE BINOCHE AND AL PACINO PRESS NOTES Running time is 93 minutes. Rated R for violence, pervasive language and brief disturbing sexual content. Press Contacts: LOS ANGELES FIELD ONLINE NEW YORK Chris Libby /Chris Regan Sumyi Khong Patrick Craig Annie McDonough 6255 Sunset Blvd., Ste. 917 9242 Beverly Blvd., Ste. 201 11 West 19th Street 850 Seventh Ave., Ste. 1005 Los Angeles, CA 90028 Beverly Hills, CA 90210 New York, NY 10011 New York, NY 10019 P: 323.645.6800 P: 424.204.4164 P: 212.386.7685 P: 212-445-7100 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] The Son of No One Synopsis In this searing police thriller, Jonathan (Channing Tatum) is a second-generation cop who gets in over his head when he’s assigned to re-open a double homicide cold case in his Queens neighborhood. An anonymous source feeding new information on the long-unsolved murders to a local reporter (Juliette Binoche) leads to evidence suggesting a possible cover-up by the former lead detective (Al Pacino), who was on the investigation. As Jonathan digs deeper into the assignment, a dark secret about the case emerges, which threatens to destroy his life and his family. Written and directed by Dito Montiel, The Son of No One also stars Tracy Morgan, Katie Holmes, Ray Liotta and Jake Cherry. -

Why Every Show Needs to Be More Like the WIRE

Why Every Show Needs to Be More Like THE WIRE (“Not Just the Facts, Ma’am.”) The Wire upends the traditional police procedural by moving past basic plot points and “twists” in the case, diving deep into the lives of both the cops and the criminals they pursue. We see this immediately in the teaser of the pilot. Detective Jimmy McNulty (Dominic West) is at the scene of a shooting, questioning a Witness (Kamal Bostic-Smith) on the murder of a boy from “round the way nicknamed “Snot Boogie.” McNulty and the Witness go back and forth on the origin of “Snot Boogie’s” nickname at first. Until the Witness explains what happened: MCNULTY So who shot Snot? WITNESS I ain’t going to no court. Motherfucker ain’t have to put no cap in him though. MCNULTY Definitely not. WITNESS He could’ve just whipped his ass, like we always whip his ass. MCNULTY I agree with you. !1 WITNESS He gonna kill Snot. Snot been doing the same shit since I don’t know how long. Kill a man over some bullshit. I’m saying, every Friday night in the alley behind the cut-rate, we rolling bones, you know? All the boys from around the way, we roll till late. MCNULTY Alley crap game, right? WITNESS And like every time, Snot, he’d fade a few shooters. Play it out till the pot’s deep. Then he’d snatch and run. MCNULTY --Every time? WITNESS —Couldn’t help hisself. MCNULTY Let me understand you. Every Friday night, you and your boys would shoot crap, right? And every Friday night, your pal Snotboogie he’d wait till there was cash on the ground, then grab the money and run away?--You let him do that? WITNESS --We catch him and beat his ass. -

Generation Kill Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GENERATION KILL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Evan Wright | 480 pages | 19 Mar 2009 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9780552158930 | English | London, United Kingdom Generation Kill PDF Book So the confidence of the Afghan people was sliding; there were more and more Afghans with a greater sense of frustration and pessimism for the future. Luckily, because of the sheer amount of water heading toward them, they heard it before it hit them and were moved out of the way before anyone was hurt. As a result, the Navy has cut the LCS program down to 40 vessels and is now looking for a new generation of frigates. But it certainly didn't solve the problems. View more newsletters on our Subscriptions page. And that was what created the need for the additional forces. It was designed to target individual missile silos, to retarget in-flight, and to survive a first strike. Michael Stinetorf 7 episodes, Channel 4 to air True Blood and Generation Kill. Combat Jack. It's cooperating with civilian agencies, it's cooperating with conventional forces, it's tying the pieces together. Sharp Objects. I've never been in a position where I had a detainee or prisoner who knew where a nuclear weapon in New York was and if I was able to get the information out of him in three hours I could save millions of people. Skins US. Where Men Win Glory. Moral courage and restraint; it was on the backs of [sergeants] and below that our military succeeded. Get the latest on pay updates, benefit changes and award-winning military content. -

Generation Kill: a Trice Told Tale the Representation of Reality in a Non-Fiction Adaptation

Generation Kill: A Trice Told Tale The representation of reality in a non-fiction adaptation Lisa van Kessel s4105974 English Language and Culture Radboud University Nijmegen June 15 2014 Dr Chris Louttit van Kessel 4105974 / 2 Abstract: In this age of mass media, it is important to be able to find the truth in between the sensationalising and embellishments, especially when it concerns controversial topics. This thesis analyses Generation Kill, the narrative of Evan Wright who is an embedded reporter that joined a platoon of First Recon Marines during the first weeks of the invasion of Iraq, on the representation of reality. Not only Evan Wright's Generation Kill (2004) - a work of literary journalism that wraps the facts in a literary jacket - will be discussed, but also the HBO adaptation Generation Kill (2008) - a fictional adaptation of a non-fiction work. The thesis will answer how Generation Kill by Evan Wright and the HBO series of the same name blur the boundary between fact and fiction and how an adaptation of a non-fiction work can provide a different perspective to the fidelity debate. Keywords: Literary journalism; adaptation studies; fidelity; non-fiction adaptation; Generation Kill. van Kessel 4105974 / 3 Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction p. 4 Chapter Two: Literary Journalism p. 9 Chapter Three: Adaptation Studies and the Fidelity Debate p. 13 Chapter Four: Analysing Generation Kill (2004) p. 17 Chapter Five: Analysing Generation Kill (2008) p. 25 Chapter Six: Conclusion p. 34 Bibliography p. 38 Essay Cover Sheet p. 41 van Kessel 4105974 / 4 Chapter 1: Introduction "True stories are never quite true, and adaptations of true stories are even less so" (Dwyer, 49). -

Glbtq Revivals and Classics

5 W. North Ave. Baltimore, MD 21201 Phone: 443-438-6144 FRIDAY JUNE 16 – THURSDAY JUNE 22 CELEBRATING PRIDE ALL WEEK! Check mdfilmfest.com for showtimes! Tickets $10/$8 members EMERGING FILMS One of our primary missions at the Parkway is to give a year-round home to the kinds of work we champion during the annual Maryland Film Festival: visionary independent films from emerging voices, as well as the latest works from international mavericks and masters! KIKI Sara Jordenö, USA, 2017, 94 minutes A dynamic coming-of-age story about resilience and the transformative art form that is voguing. Kiki offers riveting and complex insight into the daily lives of a group of LGBTQ youth-of-color who comprise the “Kiki” scene, a vibrant, safe space for per- formance created and governed by these activists. “Explodes with energy”–Variety… “a group of brave and beautiful souls”–The New York Times… “exuberant and alive, and never despairing.”–Los Angeles Times Screening all week! Check www.mdfilmfest.com for showtimes! THE ORNITHOLOGIST João Pedro Rodrigues, Brazil/Portugal, 2016, 117 minutes As he treks through the north of Portugal in search of rare birds, Fernando is swept away by the river rapids. Rescued by a couple of Chinese pilgrims, he tries to find his way back home through the eerie, dark forests, where uncanny encounters put him to the test. He soon becomes a different man, inspired, perhaps even enlightened. “You can depend on a João Pedro Rodrigues movie to give you a real eyeful. The Portuguese filmmaker’s erotic phantasmagorias offer -

112813 Largo Leader

Unemployment continues to fall Pinellas County’s rate dropped to 6.2 percent in October ... Page 7A. Disney’s animated film ‘Frozen’ hits theaters this week Also, the Chinese Golden Acrobats come to Largo Cultural Center Dec. 1 ... Page 1B. Volume XXXVI, No. 19 www.TBNweekly.com November 28, 2013 LARGO Hearing for PSTA referendum set County hashes out ballot language to change transporation funding By SUZETTE PORTER tional money would be used to improve the county’s surtax to fund Greenlight Pinellas Plan for public tran- transportation system, including the addition of rail sit.” CLEARWATER – What should come first – the levy of service. The words as well as the order of words between the the tax or the purpose for the levy? County Attorney Jim Bennett prefers ballot language two versions differs more in the summary, which also Pinellas County Commissioners spent a portion of based on what has been used in the past for Penny for must adhere to a state-set 36-word count. their Nov. 19 meeting working on the ballot language Pinellas referendums. PSTA prefers language closer to The county’s preferred wording is “Shall Pinellas Largo dance group for a Nov. 4, 2014 referendum. The county’s legal team what has been used in Hillsborough County. County levy a countywide one-percent sales tax from and attorney for Pinellas County Transit Authority have The ballot title, which is restricted by state statute to Jan. 1, 2016, until repealed or reduced by county ordi- takes top score been negotiating for weeks on how best to ask voters to 16 words, is close in both versions. -

Production Notes

SINISTER 2 Production Notes Directed by CIARÁN FOY Written by SCOTT DERRICKSON & C. ROBERT CARGILL Produced by JASON BLUM, p.g.a., SCOTT DERRICKSON, p.g.a. SINISTER 2 Synopsis Sinister 2 is the chilling sequel to the 2012 sleeper hit horror movie. In the aftermath of the shocking events in Sinister , the evil spirit of Bughuul continues to spread with frightening intensity. The new story is a scary, suspenseful race against time to save a family from falling prey to the madness, movies, and murder conjured by Bughuul and his foot soldiers, the ghost kids. 9-year-old twins Dylan and Zach Collins (portrayed by real-life brothers Robert and Dartanian Sloan) have been spirited away by their mother Courtney (Shannyn Sossamon of Wayward Pines ) to a rural house in Illinois. The home and property are just isolated enough to evade Courtney’s estranged husband Clint (Lea Coco), who has abused her and Dylan. This protective mother is unaware that the house itself is marked for death… …but Ex-Deputy So & So (James Ransone, reprising his Sinister role), now a private investigator, has deduced that the family’s hideout is the next manifestation spot for Bughuul. Determined to avenge the tragedy he was privy to while on the police force, So & So journeys to the rural residence, intending to burn it to the ground and thereby end Bughuul’s chain of death. Finding Courtney and the twins there, he realizes that they are in danger from Clint and that he must step in to help them before he can implement a plan of attack against Bughuul. -

“Little Mermaid” and “It Chapter Two” Stars Coming to Motor City Comic

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE “LITTLE MERMAID” AND “IT CHAPTER TWO” STARS COMING TO MOTOR CITY COMIC CON Disney Legend Jodi Benson will make a special appearance May 15-17, 2020 James Ransone will make a special appearance May 15-17, 2020 NOVI, MI. (January 16, 2020) – Motor City Comic Con, Michigan’s largest and longest running comic book and pop culture convention since 1989 is thrilled to announce the Disney Princess Ariel, Jodi Benson and the IT CHAPTER TWO star James Ransone will be attending this year’s con. Both Benson and Ransone will attend on Friday, May 15 – Sunday, May 17th 2020 and will host a panel Q&A, be available for autographs (Benson: $50.00; Ransone: $40.00) and photo ops (Benson: $60.00; Ransone: $40.00). To purchase tickets and for more information about autographs and photo ops, please go to – https://www.motorcitycomiccon.com/tickets/ Jodi Benson is an American actress, voice actress and singer. She is best known for providing both the speaking and the singing voice of Disney’s Princess Ariel in The Little Mermaid and its sequel, prequel, and television series spinoff. Benson voice the character Barbie in the 1999 Golden Globe winning movie Toy Story 2 and its 2010 Academy Award winning sequel Toy Story 3. She also voiced Barbie in the Toy Story cartoon Hawaiian Vacation. For her contributions to the Disney company, Benson was named a Disney Legend in 2011. Benson was the original voice of Ariel in the Academy Award winning Walt Disney Pictures animated feature film The Little Mermaid and continues to perform Ariel and the bubbly voice of “Barbie” in Disney/Pixar’s Best Picture Golden Globe Winner Toy Story 2 and Academy Award winner Toy Story 3.