Generation Kill: a Trice Told Tale the Representation of Reality in a Non-Fiction Adaptation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generation Kill and the New Screen Combat Magdalena Yüksel and Colleen Kennedy-Karpat

15 Generation Kill and the New Screen Combat Magdalena Yüksel and Colleen Kennedy-Karpat No one could accuse the American cultural industries of giving the Iraq War the silent treatment. Between the 24-hour news cycle and fictionalized enter- tainment, war narratives have played a significant and evolving role in the media landscape since the declaration of war in 2003. Iraq War films, on the whole, have failed to impress audiences and critics, with notable exceptions like Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2008), which won the Oscar for Best Picture, and her follow-up Zero Dark Thirty (2012), which tripled its budget in worldwide box office intake.1 Television, however, has fared better as a vehicle for profitable, war-inspired entertainment, which is perhaps best exemplified by the nine seasons of Fox’s 24 (2001–2010). Situated squarely between these two formats lies the television miniseries, combining seriality with the closed narrative of feature filmmaking to bring to the small screen— and, probably more significantly, to the DVD market—a time-limited story that cultivates a broader and deeper narrative development than a single film, yet maintains a coherent thematic and creative agenda. As a pioneer in both the miniseries format and the more nebulous category of quality television, HBO has taken fresh approaches to representing combat as it unfolds in the twenty-first century.2 These innovations build on yet also depart from the precedent set by Band of Brothers (2001), Steven Spielberg’s WWII project that established HBO’s interest in war-themed miniseries, and the subsequent companion project, The Pacific (2010).3 Stylistically, both Band of Brothers and The Pacific depict WWII combat in ways that recall Spielberg’s blockbuster Saving Private Ryan (1998). -

Rules of Engagement: Performance and Identity in the War on Terror

RULES OF ENGAGEMENT: PERFORMANCE AND IDENTITY IN THE WAR ON TERROR A Thesis by EMILY JO PIEPENBRINK Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies Rules of Engagement: Performance and Identity in the War on Terror Copyright 2012 Emily Jo Piepenbrink RULES OF ENGAGEMENT: PERFORMANCE AND IDENTITY IN THE WAR ON TERROR A Thesis by EMILY JO PIEPENBRINK Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, Judith Hamera Joseph G. Dawson Head of Department, Judith Hamera May 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies iii ABSTRACT Rules of Engagement: Performance and Identity in the War on Terror. (May 2012) Emily Jo Piepenbrink, B.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Kirsten Pullen War and war-fighters have become immortalized through performance; generations of service-men and women are defined by actions on the battlefield artfully altered on stage and screen. This reciprocal relationship, whether war-fighters intentionally participate or not, has imbued the entertainment industry with the power to characterize war-fighters in lasting ways. Performance enters the military in other ways as well: war-fighters reenact moments from war films; combat training takes on theatrical tactics and rhetoric; war-fighters of the War on Terror record and stage their own war performances. We accept that current war performances will inevitably affect the perception and reputation of war-fighters, not only for the duration of the war but for decades afterward, but do we fully understand the cost of the relationship between today’s war-fighters and performance’s role in the military? In this MA thesis, based on ethnographic fieldwork with veterans of the War on Terror, I explore the intersection between war-fighters, war, and performance. -

Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J

Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J. Keith Saliba, Ted Geltner Journal of Magazine Media, Volume 13, Number 2, Summer 2012, (Article) Published by University of Nebraska Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jmm.2012.0002 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/773721/summary [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 07:15 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Literary War Journalism Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J. Keith Saliba, Jacksonville University [email protected] Ted Geltner, Valdosta State University [email protected] Abstract Relatively few studies have systematically analyzed the ways literary journalists construct meaning within their narratives. This article employed rhetorical framing analysis to discover embedded meaning within the text of John Sack’s Gulf War Esquire articles. Analysis revealed several dominant frames that in turn helped construct an overarching master narrative—the “takeaway,” to use a journalistic term. The study concludes that Sack’s literary approach to war reportage helped create meaning for readers and acted as a valuable supplement to conventional coverage of the war. Keywords: Desert Storm, Esquire, framing, John Sack, literary journalism, war reporting Introduction Everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult. The difficulties accumulate and end by producing a kind of friction that is inconceivable unless one has experienced war. —Carl von Clausewitz Long before such present-day literary journalists as Rolling Stone’s Evan Wright penned Generation Kill (2004) and Chris Ayres of the London Times gave us 2005’s War Reporting for Cowards—their poignant, gritty, and sometimes hilarious tales of embedded life with U.S. -

Why Every Show Needs to Be More Like the Wire (“Not Just the Facts, Ma’Am”)

DIALOGUE WHY EVERY SHOW NEEDS TO BE MORE LIKE THE WIRE (“NOT JUST THE FACTS, MA’AM”) NEIL LANDAU University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) The Wire (HBO, 2002-2008) upends the traditional po- ed the cop-drama universe. It was a pioneering season-long lice procedural by moving past basic plot points and “twists” procedural. Here are my top 10 reasons why Every Show in the case, diving deep into the lives of both the cops and Needs to Be More Like The Wire. the criminals they pursue. It comments on today’s America, employing characters who defy stereotype. In the words of — creator David Simon: 1. “THIS AMERICA, MAN” The grand theme here is nothing less than a nation- al existentialism: It is a police story set amid the As David Simon explains: dysfunction and indifference of an urban depart- ment—one that has failed to come to terms with In the first story arc, the episodes begin what the permanent nature of urban drug culture, one would seem to be the straightforward, albeit pro- in which thinking cops, and thinking street players, tracted, pursuit of a violent drug crew that controls must make their way independent of simple expla- a high-rise housing project. But within a brief span nations (Simon 2000: 2). of time, the officers who undertake the pursuit are forced to acknowledge truths about their de- Given the current political climate in the US and interna- partment, their role, the drug war and the city as tionally, it is timely to revisit the The Wire and how it expand- a whole. -

Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq

'The Best Covered War in History': Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq by Andrew J. McLaughlin A thesis presented to the University Of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Andrew J. McLaughlin 2017 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Marco Rimanelli Professor, St. Leo University Supervisor(s) Andrew Hunt Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Jasmin Habib Associate Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Roger Sarty Professor, Wilfrid Laurier University Internal-external Member Brian Orend Professor, University of Waterloo ii Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract This study examines combat operations from the 2003 invasion of Iraq War from the “ground up.” It utilizes unique first-person accounts that offer insights into the realities of modern warfare which include effects on soldiers, the local population, and journalists who were tasked with reporting on the action. It affirms the value of media embedding to the historian, as hundreds of journalists witnessed major combat operations firsthand. This line of argument stands in stark contrast to other academic assessments of the embedding program, which have criticized it by claiming media bias and military censorship. Here, an examination of the cultural and social dynamics of an army at war provides agency to soldiers, combat reporters, and innocent civilians caught in the crossfire. -

The Wire the Complete Guide

The Wire The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 29 Jan 2013 02:03:03 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 The Wire 1 David Simon 24 Writers and directors 36 Awards and nominations 38 Seasons and episodes 42 List of The Wire episodes 42 Season 1 46 Season 2 54 Season 3 61 Season 4 70 Season 5 79 Characters 86 List of The Wire characters 86 Police 95 Police of The Wire 95 Jimmy McNulty 118 Kima Greggs 124 Bunk Moreland 128 Lester Freamon 131 Herc Hauk 135 Roland Pryzbylewski 138 Ellis Carver 141 Leander Sydnor 145 Beadie Russell 147 Cedric Daniels 150 William Rawls 156 Ervin Burrell 160 Stanislaus Valchek 165 Jay Landsman 168 Law enforcement 172 Law enforcement characters of The Wire 172 Rhonda Pearlman 178 Maurice Levy 181 Street-level characters 184 Street-level characters of The Wire 184 Omar Little 190 Bubbles 196 Dennis "Cutty" Wise 199 Stringer Bell 202 Avon Barksdale 206 Marlo Stanfield 212 Proposition Joe 218 Spiros Vondas 222 The Greek 224 Chris Partlow 226 Snoop (The Wire) 230 Wee-Bey Brice 232 Bodie Broadus 235 Poot Carr 239 D'Angelo Barksdale 242 Cheese Wagstaff 245 Wallace 247 Docks 249 Characters from the docks of The Wire 249 Frank Sobotka 254 Nick Sobotka 256 Ziggy Sobotka 258 Sergei Malatov 261 Politicians 263 Politicians of The Wire 263 Tommy Carcetti 271 Clarence Royce 275 Clay Davis 279 Norman Wilson 282 School 284 School system of The Wire 284 Howard "Bunny" Colvin 290 Michael Lee 293 Duquan "Dukie" Weems 296 Namond Brice 298 Randy Wagstaff 301 Journalists 304 Journalists of The Wire 304 Augustus Haynes 309 Scott Templeton 312 Alma Gutierrez 315 Miscellany 317 And All the Pieces Matter — Five Years of Music from The Wire 317 References Article Sources and Contributors 320 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 324 Article Licenses License 325 1 Overview The Wire The Wire Second season intertitle Genre Crime drama Format Serial drama Created by David Simon Starring Dominic West John Doman Idris Elba Frankie Faison Larry Gilliard, Jr. -

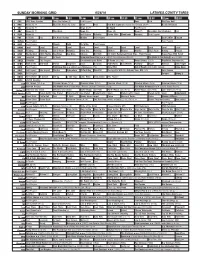

Sunday Morning Grid 6/26/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/26/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid Red Bull Signature Series From Detroit. (N) Å Beach Volleyball 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Incredible Dog Challenge Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Earth 2050 FabLab 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Happy Yoga With Sarah 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. (PG-13) The World Is Not Enough ›› (1999) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Un recuerdo para Rubé Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Firehouse Dog ›› (2007) Josh Hutcherson. -

Generation Kill (The Novel and the HBO Series) and One Bullet Away

Three Perspectives of the Iraq War: Generation Kill (the novel and the HBO Series) and One Bullet Away Feješ, Marko Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2015 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:994742 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-02 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij: Engleski jezik i književnost - pedagogija Three Perspectives on the Iraq War: Generation Kill (the Novel and the HBO Series) and One Bullet Away Završni rad Marko Feješ Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Sanja Runtić Sumentor: dr. sc. Jasna Poljak Rehlicki Lipanj, 2015. Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………… ....... 1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………….. ....... 2 1. An Overview of War Journalism……………………………………………………… 5 2. An Officer’s Position and Perspective……………………………………………….... 8 3. Enlisted Men’s Position and Perspective………………………………………….. ...... 9 4. Battle of Nasiriyah……………………………………………………………….. ..... .10 4.1. A Journalist’s Perspective………………………………………………… .. 10 4.2. An Officer’s Perspective……………………………………………………. 11 4.3. Enlisted Men’s Perspective……………………………………………... ..... 12 5. Battle of Al Muwaffaqiyah………………………………………………………. -

The Son of No One

ANCHOR BAY FILMS AND MILLENNIUM FILMS PRESENTS A NU IMAGE PRODUCTION A FILM BY DITO MONTEL The Son of No One STARRING: CHANNING TATUM TRACY MORGAN KATIE HOLMES RAY LIOTTA WITH JULIETTE BINOCHE AND AL PACINO PRESS NOTES Running time is 93 minutes. Rated R for violence, pervasive language and brief disturbing sexual content. Press Contacts: LOS ANGELES FIELD ONLINE NEW YORK Chris Libby /Chris Regan Sumyi Khong Patrick Craig Annie McDonough 6255 Sunset Blvd., Ste. 917 9242 Beverly Blvd., Ste. 201 11 West 19th Street 850 Seventh Ave., Ste. 1005 Los Angeles, CA 90028 Beverly Hills, CA 90210 New York, NY 10011 New York, NY 10019 P: 323.645.6800 P: 424.204.4164 P: 212.386.7685 P: 212-445-7100 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] The Son of No One Synopsis In this searing police thriller, Jonathan (Channing Tatum) is a second-generation cop who gets in over his head when he’s assigned to re-open a double homicide cold case in his Queens neighborhood. An anonymous source feeding new information on the long-unsolved murders to a local reporter (Juliette Binoche) leads to evidence suggesting a possible cover-up by the former lead detective (Al Pacino), who was on the investigation. As Jonathan digs deeper into the assignment, a dark secret about the case emerges, which threatens to destroy his life and his family. Written and directed by Dito Montiel, The Son of No One also stars Tracy Morgan, Katie Holmes, Ray Liotta and Jake Cherry. -

Guide to MS677 Vietnam War-Related Publications

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Finding Aids Special Collections Department 1-31-2020 Guide to MS677 Vietnam War-related publications Carolina Mercado Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/finding_aid This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections Department at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guide to MS 677 Vietnam War-related publications 1962 – 2010s Span Dates, 1966 – 1980s Bulk Dates 3 feet (linear) Inventory by Carolina Mercado July 30, 2019; January 31, 2020 Donated by Howard McCord and Dennis Bixler-Marquez. Citation: Vietnam War-related publications, MS677, C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department. The University of Texas at El Paso Library. C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department University of Texas at El Paso Historical Sketch The Vietnam War (1954 – 1975) was a military conflict between the communist North Vietnamese (Viet Cong) and its allies and the government of South Vietnam and its allies (mainly the United States). The North Vietnamese sought to unify Vietnam under a communist regime, while South Vietnam wanted to retain its government, which was aligned with the West. The war was also a result of the ongoing Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. On July 2, 1976 the North Vietnamese united the country after the South Vietnamese government surrendered on April 30. Millions of soldiers and civilians were killed during the Vietnam War. [Source: Encyclopedia Britannica, “The Vietnam War,” accessed on January 31, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War] Series Description or Arrangement This collection was left in the order found by the archivist. -

LJS Cortland, New York 13045-0900 U.S.A

LiteraryStudies Journalism Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring 2009 Return address: Literary Journalism Studies State University of New York at Cortland Department of Communication Studies P.O. Box 2000 LJS Cortland, New York 13045-0900 U.S.A. Literary Journalism Studies Inaugural Issue The Problem and the Promise of Literary Journalism Studies by Norman Sims An exclusive excerpt from the soon-to-be-released narrative nonfiction account, published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux Tears in the Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and Its Aftermath by Michael and Elizabeth Norman Writing Narrative Portraiture by Michael Norman South: Where Travel Meets Literary Journalism by Isabel Soares Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring 2009 2009 Spring 1, No. 1, Vol. “My Story Is Always Escaping into Oher People” by Robert Alexander Differently Drawn Boundaries of the Permissible by Beate Josephi and Christine Müller Recovering the Peculiar Life and Times of Tom Hedley and of Canadian New Journalism by Bill Reynolds Published at the Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University 1845 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208, U.S.A. The Journal of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies On the Cover he ghost image in the background of our cover is based on this iconic photo Tof American prisoners-of-war, hands bound behind their backs, who took part in the 1942 Bataan Death March. The Death March is the subject of Michael and Elizabeth M. Norman’s forthcoming Tears in the Darkness, pub- lished by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Excerpts begin on page 33, followed by an essay by Michael Norman on the challenges of writing the book, which required ten years of research, travel, and interviewing American and Filipino surivivors of the march, as well as Japanese participants. -

The Inventory of the John Sack Collection #1121

The Inventory of the John Sack Collection #1121 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center BOSTON UNIVERSITY Sack, John #1121 2/19/76; 2/27/76; 3/12/76; 4/6/76; 9/24/80; 1/7/81; 6/29/83; 3/14/89 Preliminary Listing I. Professional Materials. A. Office Files; may include manuscripts; correspondence; printed materials; research materials; financial materials; legal materials; photographs; notebooks; manuscripts by others. Box 1 1. ”ADS Afloat,” n.d. [F. 1] 2. “Africa,” n.d. 3. “After Army,” n.d. 4. “After Mylai,” n.d. 5. “Afterwards: Medlo’s Foot,” n.d. 6. “Afterwards: Night,” n.d. 7. “Afterwards: Nurse,” n.d. 8. “Afterwards: Return,” n.d. 9. “Airplanes (Shoot Down),” 1964. 10. “Album,” 1963-1964. 11. “All are VC,” n.d. 12. “All are VC: Duties,” n.d. 13. “All are VC (Higher HQ),” n.d. 14. “All are VC: Kill Them,” n.d. 15. “All are VC: Kill them (Higher HQ),” n.d. [F. 2] 16. “All are VC: No,” n.d. 17. “America and Vietnam,” n.d. 18. “America and Vietnam: What to Do,” n.d. 19. “Ancient Scripts,” 1962. 20. “Animals,” n.d. 21. “Apartments in East Europe,” n.d. 22. “Army Philosophy,” n.d. 23. “Arrival in Vietnam,” n.d. 24. “Artillery,” n.d. 25. “Attitude on Arrival in Vietnam,” n.d. 26. “Auto Junkyards,” 1956-1965. 27. “Baby Count Stories,” n.d. [F. 3] 28. “Baldness Cure,” n.d. 29. “Big Ear,” 1964-1965. 30. “Biographs,” n.d. 31. “Bobby,” 1964. 32. “Book Count,” n.d. 33. “Bottles and Boats,” 1964.