1 Capturing Iraq: Optical Focalization in Contemporary War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generation Kill and the New Screen Combat Magdalena Yüksel and Colleen Kennedy-Karpat

15 Generation Kill and the New Screen Combat Magdalena Yüksel and Colleen Kennedy-Karpat No one could accuse the American cultural industries of giving the Iraq War the silent treatment. Between the 24-hour news cycle and fictionalized enter- tainment, war narratives have played a significant and evolving role in the media landscape since the declaration of war in 2003. Iraq War films, on the whole, have failed to impress audiences and critics, with notable exceptions like Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2008), which won the Oscar for Best Picture, and her follow-up Zero Dark Thirty (2012), which tripled its budget in worldwide box office intake.1 Television, however, has fared better as a vehicle for profitable, war-inspired entertainment, which is perhaps best exemplified by the nine seasons of Fox’s 24 (2001–2010). Situated squarely between these two formats lies the television miniseries, combining seriality with the closed narrative of feature filmmaking to bring to the small screen— and, probably more significantly, to the DVD market—a time-limited story that cultivates a broader and deeper narrative development than a single film, yet maintains a coherent thematic and creative agenda. As a pioneer in both the miniseries format and the more nebulous category of quality television, HBO has taken fresh approaches to representing combat as it unfolds in the twenty-first century.2 These innovations build on yet also depart from the precedent set by Band of Brothers (2001), Steven Spielberg’s WWII project that established HBO’s interest in war-themed miniseries, and the subsequent companion project, The Pacific (2010).3 Stylistically, both Band of Brothers and The Pacific depict WWII combat in ways that recall Spielberg’s blockbuster Saving Private Ryan (1998). -

Rules of Engagement: Performance and Identity in the War on Terror

RULES OF ENGAGEMENT: PERFORMANCE AND IDENTITY IN THE WAR ON TERROR A Thesis by EMILY JO PIEPENBRINK Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies Rules of Engagement: Performance and Identity in the War on Terror Copyright 2012 Emily Jo Piepenbrink RULES OF ENGAGEMENT: PERFORMANCE AND IDENTITY IN THE WAR ON TERROR A Thesis by EMILY JO PIEPENBRINK Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, Judith Hamera Joseph G. Dawson Head of Department, Judith Hamera May 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies iii ABSTRACT Rules of Engagement: Performance and Identity in the War on Terror. (May 2012) Emily Jo Piepenbrink, B.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Kirsten Pullen War and war-fighters have become immortalized through performance; generations of service-men and women are defined by actions on the battlefield artfully altered on stage and screen. This reciprocal relationship, whether war-fighters intentionally participate or not, has imbued the entertainment industry with the power to characterize war-fighters in lasting ways. Performance enters the military in other ways as well: war-fighters reenact moments from war films; combat training takes on theatrical tactics and rhetoric; war-fighters of the War on Terror record and stage their own war performances. We accept that current war performances will inevitably affect the perception and reputation of war-fighters, not only for the duration of the war but for decades afterward, but do we fully understand the cost of the relationship between today’s war-fighters and performance’s role in the military? In this MA thesis, based on ethnographic fieldwork with veterans of the War on Terror, I explore the intersection between war-fighters, war, and performance. -

Bigelow Masculinity

Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2011) Article TOUGH GUY IN DRAG? HOW THE EXTERNAL, CRITICAL DISCOURSES SURROUNDING KATHRYN BIGELOW DEMONSTRATE THE WIDER PROBLEMS OF THE GENDER QUESTION. RONA MURRAY, De Montford University ABSTRACT This article argues that the various approaches adopted towards Kathryn Bigelow’s work, and their tendency to focus on a gendered discourse, obscures the wider political discourses these texts contain. In particular, by analysing the representation of masculinity across the films, it is possible to see how the work of this director and her collaborators is equally representative of its cultural context and how it uses the trope of the male body as a site for a dialectical study of the uses and status of male strength within an imperialistically-minded western society. KEYWORDS Counter-cultural, feminism, feminist, gender, masculinity, western. ISSN 1755-9944 1 Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2011) Whether the director Kathryn Bigelow likes it or not, gender has been made to lie at the heart of her work, not simply as it figures in her texts but also as it is used to initiate discussion about her own function/place as an auteur? Her career illustrates how the personal becomes the political not via individual agency but in the way she has come to stand as a particular cultural symbol – as a woman directing men in male-orientated action genres. As this persona has become increasingly loaded with various significances, it has begun to alter the interpretations of her films. -

Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The Hurt Locker"

Cinesthesia Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 12-1-2012 Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The urH t Locker" Kelly Meyer Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Kelly (2012) "Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The urH t Locker"," Cinesthesia: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol1/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cinesthesia by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Meyer: Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The Hurt Locker" Cinematic Realism in Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker No one has ever seen Baghdad. At least not like explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) squad leader William James has, through a lens of intense adrenaline and deathly focus. In the 2008 film The Hurt Locker, director Katherine Bigelow creates a striking realist portrait of an EOD team on their tour of Baghdad. Bigelow’s use of deep focus and wide- angle shots in The Hurt Locker exemplify the realist concerns of French film theorist André Bazin. Early film theory has its basis in one major goal: to define film as art in its own right. In What is Film Theory, authors Richard Rushton and Gary Bettinson state that “…each theoretical inquiry converges on a common objective: to defend film as a distinctive and authentic mode of art” (8). Many theorists argue relevant and important points regarding film, some from a formative point of view and others from a realist view. -

Film & Literature

Name_____________________ Date__________________ Film & Literature Mr. Corbo Film & Literature “Underneath their surfaces, all movies, even the most blatantly commercial ones, contain layers of complexity and meaning that can be studied, analyzed and appreciated.” --Richard Barsam, Looking at Movies Curriculum Outline Form and Function: To equip students, by raising their awareness of the development and complexities of the cinema, to read and write about films as trained and informed viewers. From this base, students can progress to a deeper understanding of film and the proper in-depth study of cinema. By the end of this course, you will have a deeper sense of the major components of film form and function and also an understanding of the “language” of film. You will write essays which will discuss and analyze several of the films we will study using accurate vocabulary and language relating to cinematic methods and techniques. Just as an author uses literary devices to convey ideas in a story or novel, filmmakers use specific techniques to present their ideas on screen in the world of the film. Tentative Film List: The Godfather (dir: Francis Ford Coppola); Rushmore (dir: Wes Anderson); Do the Right Thing (dir: Spike Lee); The Dark Knight (dir: Christopher Nolan); Psycho (dir: Alfred Hitchcock); The Graduate (dir: Mike Nichols); Office Space (dir: Mike Judge); Donnie Darko (dir: Richard Kelly); The Hurt Locker (dir: Kathryn Bigelow); The Ice Storm (dir: Ang Lee); Bicycle Thives (dir: Vittorio di Sica); On the Waterfront (dir: Elia Kazan); Traffic (dir: Steven Soderbergh); Batman (dir: Tim Burton); GoodFellas (dir: Martin Scorsese); Mean Girls (dir: Mark Waters); Pulp Fiction (dir: Quentin Tarantino); The Silence of the Lambs (dir: Jonathan Demme); The Third Man (dir: Carol Reed); The Lord of the Rings trilogy (dir: Peter Jackson); The Wizard of Oz (dir: Victor Fleming); Edward Scissorhands (dir: Tim Burton); Raiders of the Lost Ark (dir: Steven Spielberg); Star Wars trilogy (dirs: George Lucas, et. -

Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty Or a Visionary?

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2016 Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? Courtney Richardson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Richardson, Courtney, "Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary?" (2016). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 107. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/107 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? By Courtney Richardson An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Shaun Huston, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2016 2 Acknowledgements First I would like to say a big thank you to my advisor Dr. Shaun Huston. He agreed to step in when my original advisor backed out suddenly and without telling me and really saved the day. Honestly, that was the most stressful part of the entire process and knowing that he was available if I needed his help was a great relief. Second, a thank you to my Honors advisor Dr. -

April 14 2019

APRIL 5 - APRIL 14 SPONSORSHIP 2019 323 Central Ave | Sarasota, FL 34236 | www.sarasotafilmfestival.com | 941.364.9514 A 501(C)(3) Non Profit Organization The Sarasota Film Festival is a ten-day celebration of the art of filmmaking and the contribution that film makes to our culture. Celebrating 21 years and beyond, SFF has an esteemed reputation as a destination festival while providing a platform for filmmakers in all stages of their careers locally, nationally, and globally. 2018 Sarasota Film Festival 14 56 43 124 World Documentary Narrative Shorts Premieres Features Features 2 MEET OUR ATTENDEES 3 About our Attendees SFF patrons are well educated, brand savvy, sponsor friendly and have high disposable income. With a satisfaction rating over 90%, our audiences are loyal and engaged throughout the Festival. • Physical Attendance 50,000 + patrons • 80% live in Sarasota year-round • 20% make over $200,000/year • 47% own two or more homes • 55% make $100k/year with average income of • 72% earn more than double the median $122,000 income of other Florida residents • 91% have bachelor’s degree or above • 55% regular retail shoppers • 26% Male • 40% drive a luxury vehicle • 73% Female 4 Social, Digital, and Traditional Media Impressions • Social Media delivers 3+ million impressions annually • IMDb partnership delivers 3+ million impressions • Television advertising delivers 2+ million impressions • Film guide reaches 250k+ viewers • Website delivers 1+ million impressions • Email list of 10k+ patrons • On-screen theatrical branding reaches 50k+ patrons • Press outlets include Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, IndieWire, and IMDb 5 FILM REPRESENTATION 6 Sarasota Film Festival programmers find the best in indie cinema to present a diverse array of domestic, foreign, and studio films that receive critical acclaim, national and international awards consideration. -

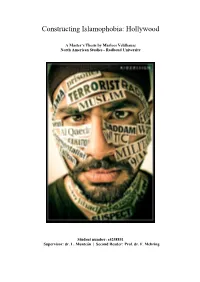

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood A Master’s Thesis by Marloes Veldhausz North American Studies - Radboud University Student number: s4258851 Supervisor: dr. L. Munteán | Second Reader: Prof. dr. F. Mehring Veldhausz 4258851/2 Abstract Islam has become highly politicized post-9/11, the Islamophobia that has followed has been spread throughout the news media and Hollywood in particular. By using theories based on stereotypes, Othering, and Orientalism and a methodology based on film studies, in particular mise-en-scène, the way in which Islamophobia has been constructed in three case studies has been examined. These case studies are the following three Hollywood movies: The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, and American Sniper. Derogatory rhetoric and mise-en-scène aspects proved to be shaping Islamophobia. The movies focus on events that happened post- 9/11 and the ideological markers that trigger Islamophobia in these movies are thus related to the opinions on Islam that have become widespread throughout Hollywood and the media since; examples being that Muslims are non-compatible with Western societies, savages, evil, and terrorists. Keywords: Islam, Muslim, Arab, Islamophobia, Religion, Mass Media, Movies, Hollywood, The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, American Sniper, Mise-en-scène, Film Studies, American Studies. 2 Veldhausz 4258851/3 To my grandparents, I can never thank you enough for introducing me to Harry Potter and thus bringing magic into my life. 3 Veldhausz 4258851/4 Acknowledgements Thank you, first and foremost, to dr. László Munteán, for guiding me throughout the process of writing the largest piece of research I have ever written. I would not have been able to complete this daunting task without your help, ideas, patience, and guidance. -

American Myth-Busting

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship & Creative Works 2012 American Myth-Busting Joe Wilkins Linfield College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/englfac_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Nonfiction Commons DigitalCommons@Linfield Citation Wilkins, Joe, "American Myth-Busting" (2012). Faculty Publications. Published Version. Submission 17. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/englfac_pubs/17 This Published Version is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Published Version must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. MEDIA THE ARTS much sway in our contemporary cul- American Myth-Busting tural psyche, consider instead Rambo, or A the latest iteration of Die Hard, or even new breed ofwesterns tells it like it is The Hurt Locker- really any big-screen BY JOE WILKINS affair featuring an honorable, lonely, de- cidedly masculine hero staring down the bad guys. Truly, many of the shoot' em-up GROWING UP ON THE PLAINS of eastern history ofcivilization , the event which in blockbusters we see each summer are di- Montana, I saw my fair share of westerns. spite of stupendous difficulties was con- rect mythological descendants of those We didn't have a VCR when I was a boy, and summated more swiftly, more completely, dime-novel westerns, which posited that, my mother didn't allow us to watch much more satisfactorily than any like event with right intention, violence will lead to TV, but westerns were part ofthe general at- since the westward migration began-I stability and community; that the present mosphere. -

America and the Movies What the Academy Award Nominees for Best Picture Tell Us About Ourselves

AMERICA AND THE MOVIES WHAT THE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINEES FOR BEST PICTURE TELL US ABOUT OURSELVES I am glad to be here, and honored. For twenty-two years, I was the Executive Director of the Center for Christian Study in Charlottesville, VA, adjacent to the University of Virginia, and now I am in the same position with the fledgling Consortium of Christian Study Centers, a nation-wide group of Study Centers with the mission of working to present a Christian voice at the secular universities of our land. There are some thirty to thirty-five such Study Centers in all different shapes and sizes. Not surprisingly, I suppose, I believe the work they are doing is some of the most important work being done at universities in America today, and that makes me glad and filled with anticipation to be here with Missy and the rest of you at the beginning of another study center. I have had the privilege of being part of this from the beginning though also from afar, and it is nice finally to see what is happening here. I look forward to seeing what the Lord does in the coming years. Thank you for inviting me to address you. Now to the task at hand. This is the tenth year in a row I have, in one form or another, looked at the Academy Award nominees for best picture and opined on what they tell us about life in American society. However, this is the first of those ten years in which I have lectured on this topic before the nominees were even announced. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

The Gulf War Aesthetic? Certain Tendencies in Image, Sound and the Construction of Space in Green Zone and the Hurt Locker

The Gulf War Aesthetic? Certain Tendencies in Image, Sound and the Construction of Space in Green Zone and The Hurt Locker Kingsley Marshall Submitted to the University of East Anglia as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film. University of East Anglia School of Art, Media & American Studies January 2018 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Word Count: 84983 Abstract This thesis argues that the perception of realism and ‘truth’ within narrative feature films set within the Gulf War (1990-1991) and Iraq War (2003-2011) is bound up in other transmedia representations of these conflicts. I identify and define what I describe as the Gulf War Aesthetic, and argue that an understanding of the ‘real life’ of the war film genre through its telling in news reportage, documentary and combatant-originated footage serves as a gateway through which the genre of fictional feature films representing the conflicts and their aftermath is constructed. I argue that the complexity of the Iraq War, coupled with technological shifts in the acquisition and distribution of video and audio through online video-sharing platforms including YouTube, further advanced the Gulf War Aesthetic. I identify The Hurt Locker (Bigelow, 2009) and Green Zone (Greengrass, 2010) as helpful case studies to evidence these changes, and subject both to detailed analysis.