Purchase by an English Company of Its Own Shares Irving J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

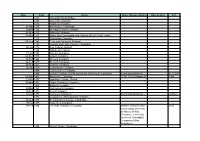

Date Year Name Name Changes/Notes Date Sealed Ref

Date Year Name Name Changes/Notes Date Sealed Ref. 1231 University of Cambridge 1248 University of Oxford 1272 Saddlers Company 28-May 1284 Peterhouse, Cambridge 10-Mar 1326 Merchant Taylors Company 01-Mar 1327 Skinners Company 06-Mar 1327 Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London 1327 Goldsmiths Company 06-Aug 1348 Dean and Canons of Windsor 1348 Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge 30-Jun 1379 New College, Oxford 1382 Winchester College 13-Jan 1393 Mercers Company 04-Dec 1416 Cutlers Company 16-Feb 1428 Grocers Company 22-Feb 1437 Brewers Company 23-Aug 1437 Vintners Company 26-Apr 1439 Cordwainers Company 1444 Leathersellers Company 1448 Queen's College of St Margaret and St Bernard, Cambridge Commonly known as 513 C993 08-May 1453 Armourers Company 17.06.1708 Company of C996 13-Oct 1457 Magdalen College, Oxford 08-Mar 1462 Tallow Chandlers Company 1462 Barbers Company 20-Mar 1463 Ironmongers Company 16-Feb 1471 Dyers Company 20-Jan 1473 Pewterers Company Commonly known as C495(2) 1474 Corporation of Blacksmith's of Dublin 16-Aug 1475 St. Catharine's College, Cambridge 07-Jul 1477 Carpenters Company 16-Feb 1484 The Wax Chandlers Company "Master, Wardens and C651 Commonalty of the Art or Mistery of Wax Chandlers" commonly known as "Worshipful Company of Wax Chandlers" 1496 Jesus College, Cambridge Date Year Name Name Changes/Notes Date Sealed Ref. 10-Mar 1501 Plaisterers Company 29-Apr 1501 Coopers Company 23-Feb 1504 Poulters Company 22-Jul 1509 Bakers Company 15-Jan 1512 Brasenose College, Oxford 1517 Corpus Christi -

The Prince's Trust - Wikipedia

1/27/2021 The Prince's Trust - Wikipedia The Prince's Trust The Prince's Trust is a charity in the United Kingdom founded in 1976 by Charles, Prince of Wales, to help vulnerable young people get their lives The Prince's Trust on track. It supports 11 to 30-year-olds who are unemployed and those struggling at school and at risk of exclusion. Many of the young people helped by The Trust are in or leaving care, facing issues such as homelessness or mental health problems, or have been in trouble with the law. It runs a range of training programmes, providing practical and financial support to build young people's confidence and motivation. Each year they work with about 60,000 young people; with three in four moving on to employment, education, volunteering or training. Formation 1976 In 1999, the numerous Trust charities were brought together as The Founder Charles, Prince of Prince's Trust and was acknowledged by The Queen at a ceremony in Wales Buckingham Palace where she granted it a Royal Charter. The following Type Charity year it devolved in Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and other English regions but overall control remained in London. The Prince's Trust Purpose The development fundraising and campaign events are often hosted and feature entertainers and improvement of from around the world. In April 2011 the youth charity Fairbridge became young people [3] part of the Trust. In 2015, Prince's Trust International was launched to Location London, SE1 collaborate with other charities and organisations in other countries United Kingdom -

Record of Charters Granted

Date Year Name Name Changes/Notes Date Sealed 1231 University of Cambridge 1248 University of Oxford 1272 Saddlers Company 28-May 1284 Peterhouse, Cambridge 10-Mar 1326 Merchant Taylors Company 1-Mar 1327 Skinners Company 6-Mar 1327 Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London 1327 Goldsmiths Company 6-Aug 1348 Dean and Canons of Windsor 1348 Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge 30-Jun 1379 New College, Oxford 1382 Winchester College 13-Jan 1393 Mercers Company 4-Dec 1416 Cutlers Company 16-Feb 1428 Grocers Company 22-Feb 1437 Brewers Company 23-Aug 1437 Vintners Company 26-Apr 1439 Cordwainers Company 1444 Leathersellers Company The Wardens and Society of the Mistery or Art of the Leathersellers of the City of London (Charter 1604) Date Year Name Name Changes/Notes Date Sealed 1448 Queen's College of St Margaret and St Bernard, Cambridge Commonly known as "Queens' College, Cambridge" 8-May 1453 Armourers Company 17.06.1708 Company of Armourers and Brasiers in the City of London 13-Oct 1457 Magdalen College, Oxford 8-Mar 1462 Tallow Chandlers Company 1462 Barbers Company 20-Mar 1463 Ironmongers Company 16-Feb 1471 Dyers Company 20-Jan 1473 Pewterers Company Commonly known as "Worshipful Company of Pewterers" 1474 Corporation of Blacksmith's of Dublin 16-Aug 1475 St. Catharine's College, Cambridge 7-Jul 1477 Carpenters Company 16-Feb 1484 The Wax Chandlers Company "Master, Wardens and Commonalty of the Art or Mistery of Wax Chandlers" commonly known as "Worshipful Company of Wax Chandlers" 1496 Jesus College, Cambridge 10-Mar -

Aip ^R Vtoautt - a POLITICAL and IITERARY REVIEW

¦ ¦ ¦ ¦ s 1 ¦ * ¦' """ ' ' '¦ ¦ '¦ ' ' ¦ " ¦ ¦ ' ' ¦ ¦ ¦ ¦ ¦ " ¦ " ' ¦ ¦ ¦ " ¦ ¦ ¦¦— - - - ¦ ¦ i - ¦ : •"'¦V-r-r .rTf-y '- ¦-- ¦ - ¦ -¦ ' ¦ . ¦ - ¦ " " --¦•- - • ¦ ¦ ¦ ' ¦ " - ; - ' ¦ ¦ ' "* . ' \ : - . ., >^ . *•« £* ; ; . - , . - ~~~-y9-- - . Jf -j -fl • . s . - . - . ^ -1 j *:¦ ¦:, ' aM ^ ^^ W ^IA^ ; W^ ^aH -d aip ^r vtoAutt - A POLITICAL AND IITERARY REVIEW. : " The one Ide a •which. History exhibits as evermore develop ing itself /into greater distinctness is ttte Idea of Humanity —the nbb 'o endeavour to throw down all the barxiacs erected between men. by prej udice and one-sided views ; and , by setting ^sxde the distinctions of Behgion , Country , and Colour , to treat the whole Human ra. ee as one brotherhood , having one great object—the free development of our spiritual nature. " —JKumboldt' s Cosmos. ¦ ¦ ' ' • ' ' ¦ ' ' ' ' ¦" " ' ' ¦ ' ' : ¦ - ¦ ¦ . : ¦ ¦ - : " - " ¦: "/ ¦ /'¦; ; , . —= —-— : :— .—;— : . -\ . ?;Tt .c v-;t . - ' ¦ ¦ ¦ ' ' ' ¦ ¦ ' ¦ ¦ ' - ' ¦ ¦ • ¦ ¦ ' ¦ ¦ • ¦ • ' ¦ ' ' ; - ¦ ' : : . - . , ¦ . ;¦ ¦¦ . • - . .. ©ontent s :. _ . , . /REVIEW OF THE 'WEEK— page Oar Civilization 919 Tho Hope of tho Work hcuse ......... 025 Napoleon in Russia 929 ¦ Vh»«i,™5»L>mT™w7,tv an915 Accidents and Sudden 3>eaths ...... 920 Tbo New Commerce of Liverpool... 920 . Tlie New Translation of the Bible . 930 /¦ ¦¦ 1 ¦'*¦ Hiawatba ¦ ajfflfSSSTSffipi*=a"iSi . ^S^^S^^^.=:±f^ """'""7""""' •" * "'"'""'""• • "' ¦ ^ oSSSS . ¦ t^Ss-T - ¦ a^fi SS^S-S r;=::::::::::::::::::::: ¦ -:::::::::::: g' ^5onda, Evening concert,..... 9a2 Rress.... 918 -

Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2015 Q1

Quarterly Bulletin 2015 Q1 | Volume 55 No. 1 Quarterly Bulletin 2015 Q1 | Volume 55 No. 1 Contents Topical articles Investment banking: linkages to the real economy and the financial system 4 Box Regulatory changes and investment banks 16 Desperate adventurers and men of straw: the failure of City of Glasgow Bank and its enduring impact on the UK banking system 23 Box Amalgamation in the British banking system 32 Capital in the 21st century 36 Box Putting capital in the 21st century in context — Thomas Piketty 39 Box Where has modern equality come from? Lucky and smart paths in economic history — Peter Lindert 40 Box Human capital and inequality in the United Kingdom — Orazio Attanasio and Richard Blundell 41 Box The metamorphosis of wealth in the 21st century — Jaume Ventura 42 Box State capacities and inequality — Timothy Besley 43 The Agencies and ‘One Bank’ 47 Box Recent changes to the Bank of England and the creation of ‘One Bank’ 48 Box Agents’ national scores 51 Self-employment: what can we learn from recent developments? 56 Flora and fauna at the Bank of England 67 Recent economic and financial developments Markets and operations 76 Box Recent moves in the price of oil 78 Report Big data and central banks 86 Summaries of working papers Summaries of recent Bank of England working papers 96 – Evaluating the robustness of UK term structure decompositions using linear regression methods 96 – Long-term unemployment and convexity in the Phillips curve 97 – A forecast evaluation of expected equity return measures 98 – Do contractionary -

The Case of Bank Regulation in Britain and the United States

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 1999 Convergence and Competition: The Case of Bank Regulation in Britain and the United States Heidi Mandanis Schooner The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Michael Taylor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Heidi Mandanis Schooner & Michael Taylor, Convergence and Competition: The Case of Bank Regulation in Britain and the United States, 20 MICH. J. INT’L L. 595 (1999). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONVERGENCE AND COMPETITION: THE CASE OF BANK REGULATION IN BRITAIN AND THE UNITED STATES Heidi Mandanis Schooner* and Michael Taylor** INTRODU CTION .................................................................................. 596 I. CONVERGENCE BY COMPETITION ............................................... 599 II. HISTORY OF UNITED STATES AND UNITED KINGDOM PRUDENTIAL REGULATION ........................................................ 605 A . Early Regulation............................................................... 606 1. U.K.'s -

The Case of Bank Regulation in Britain and the United States

Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 20 Issue 4 1999 Convergence and Competition: The Case of Bank Regulation in Britain and the United States Heidi Mandanis Schooner Columbus School of Law, Catholic University of America Michael Taylor International Monetary Fund Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Heidi M. Schooner & Michael Taylor, Convergence and Competition: The Case of Bank Regulation in Britain and the United States, 20 MICH. J. INT'L L. 595 (1999). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol20/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONVERGENCE AND COMPETITION: THE CASE OF BANK REGULATION IN BRITAIN AND THE UNITED STATES Heidi Mandanis Schooner* and Michael Taylor** INTRODU CTION .................................................................................. 596 I. CONVERGENCE BY COMPETITION ............................................... 599 II. HISTORY OF UNITED STATES AND UNITED KINGDOM PRUDENTIAL REGULATION ........................................................ 605 A . Early Regulation.............................................................. -

1 Law and Finance in Emerging Economies: Germany And

LAW AND FINANCE IN EMERGING ECONOMIES: GERMANY AND BRITAIN 1800-1913 Carsten Gerner-Beuerle* ABSTRACT By most standards, Britain in the 19th century was the leading financial nation in the world, possessing more developed capital markets than any other country. An influential view in the law and finance literature argues that holding macroeconomic factors constant, this difference in financial development can be attributed to more stringent disclosure regulation in Britain. This article compares Britain with another European country that was at the centre of the industrial transformation in the 19th century: Germany. It presents a more granular analysis of regulatory reform than is available elsewhere in the literature and presents findings that are, in several respects, at variance with the orthodox view in law and finance. The level of disclosure regulation was largely comparable in both countries during the period under investigation. Furthermore, reform of disclosure regulation was not an exogenous stimulus of financial development, but evolved incrementally and in response to changing market conditions. This was different with respect to the legal regime governing the formation of stock corporations. Here, the two countries developed in diametrically opposed directions as a result of concerted efforts by the policy maker to effect changes in market conditions. The article argues that these rules stand out as the most striking difference between Germany and the UK, a difference that was relevant to organisational choice and types of finance available to the entrepreneur. Keywords: Law and finance; financial development; disclosure regulation; private enforcement; liability for incorrect disclosures * Law Department, London School of Economics and Political Science.