Battle on Many Fronts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alameda, a Geographical History, by Imelda Merlin

Alameda A Geographical History by Imelda Merlin Friends of the Alameda Free Library Alameda Museum Alameda, California 1 Copyright, 1977 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 77-73071 Cover picture: Fernside Oaks, Cohen Estate, ca. 1900. 2 FOREWORD My initial purpose in writing this book was to satisfy a partial requirement for a Master’s Degree in Geography from the University of California in Berkeley. But, fortunate is the student who enjoys the subject of his research. This slim volume is essentially the original manuscript, except for minor changes in the interest of greater accuracy, which was approved in 1964 by Drs. James Parsons, Gunther Barth and the late Carl Sauer. That it is being published now, perhaps as a response to a new awareness of and interest in our past, is due to the efforts of the “Friends of the Alameda Free Library” who have made a project of getting my thesis into print. I wish to thank the members of this organization and all others, whose continued interest and perseverance have made this publication possible. Imelda Merlin April, 1977 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to acknowledge her indebtedness to the many individuals and institutions who gave substantial assistance in assembling much of the material treated in this thesis. Particular thanks are due to Dr. Clarence J. Glacken for suggesting the topic. The writer also greatly appreciates the interest and support rendered by the staff of the Alameda Free Library, especially Mrs. Hendrine Kleinjan, reference librarian, and Mrs. Myrtle Richards, curator of the Alameda Historical Society. The Engineers’ and other departments at the Alameda City Hall supplied valuable maps an information on the historical development of the city. -

Section 3.4 Biological Resources 3.4- Biological Resources

SECTION 3.4 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.4- BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.4 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES This section discusses the existing sensitive biological resources of the San Francisco Bay Estuary (the Estuary) that could be affected by project-related construction and locally increased levels of boating use, identifies potential impacts to those resources, and recommends mitigation strategies to reduce or eliminate those impacts. The Initial Study for this project identified potentially significant impacts on shorebirds and rafting waterbirds, marine mammals (harbor seals), and wetlands habitats and species. The potential for spread of invasive species also was identified as a possible impact. 3.4.1 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES SETTING HABITATS WITHIN AND AROUND SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY The vegetation and wildlife of bayland environments varies among geographic subregions in the bay (Figure 3.4-1), and also with the predominant land uses: urban (commercial, residential, industrial/port), urban/wildland interface, rural, and agricultural. For the purposes of discussion of biological resources, the Estuary is divided into Suisun Bay, San Pablo Bay, Central San Francisco Bay, and South San Francisco Bay (See Figure 3.4-2). The general landscape structure of the Estuary’s vegetation and habitats within the geographic scope of the WT is described below. URBAN SHORELINES Urban shorelines in the San Francisco Estuary are generally formed by artificial fill and structures armored with revetments, seawalls, rip-rap, pilings, and other structures. Waterways and embayments adjacent to urban shores are often dredged. With some important exceptions, tidal wetland vegetation and habitats adjacent to urban shores are often formed on steep slopes, and are relatively recently formed (historic infilled sediment) in narrow strips. -

Executive Director's Recommendation Regarding Proposed Cease And

May 16, 2019 TO: Enforcement Committee Members FROM: Larry Goldzband, Executive Director, (415/352-3653; [email protected]) Marc Zeppetello, Chief Counsel, (415/352-3655; [email protected]) Karen Donovan, Attorney III, (415/352-3628; [email protected]) SUBJECT: Executive Director’s Recommendation Regarding Proposed Cease and Desist and Civil Penalty Order No. CDO 2019.001.00 Salt River Construction Corporation and Richard Moseley (For Committee consideration on May 16, 2019) Executive Director’s Recommendation The Executive Director recommends that the Enforcement Committee adopt this Recommended Enforcement Decision including the proposed Cease and Desist and Civil Penalty Order No. CCD2019.001.00 (“Order”) to Salt River Construction Corporation and Richard Moseley (“SRCC”), for the reasons stated below. This matter arises out of an enforcement action commenced by BCDC staff in June of 2018 after BCDC received information from witnesses regarding the unauthorized activities. The matter was previously presented to the Enforcement Committee on February 21, 2019. After the Committee voted to recommend the adoption of the proposed Cease and Desist and Civil Penalty Order, the Commission remanded the matter to the Committee on April 18, 2019, in order to allow Mr. Moseley to appear and present his position. Staff Report I. SUMMARY OF THE BACKGROUND ON THE ALLEGED VIOLATIONS A. Background Facts The Complaint alleges three separate violations. The first alleged violation occurred on property near Schoonmaker Point Marina, located in Richardson’s Bay in Marin County. On November 25, 2017, a San Francisco Baykeeper patrol boat operator witnessed a barge near Schoonmaker Marina being propelled by an excavator bucket. -

San Francisco Bay Plan

San Francisco Bay Plan San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission In memory of Senator J. Eugene McAteer, a leader in efforts to plan for the conservation of San Francisco Bay and the development of its shoreline. Photo Credits: Michael Bry: Inside front cover, facing Part I, facing Part II Richard Persoff: Facing Part III Rondal Partridge: Facing Part V, Inside back cover Mike Schweizer: Page 34 Port of Oakland: Page 11 Port of San Francisco: Page 68 Commission Staff: Facing Part IV, Page 59 Map Source: Tidal features, salt ponds, and other diked areas, derived from the EcoAtlas Version 1.0bc, 1996, San Francisco Estuary Institute. STATE OF CALIFORNIA GRAY DAVIS, Governor SAN FRANCISCO BAY CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION 50 CALIFORNIA STREET, SUITE 2600 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94111 PHONE: (415) 352-3600 January 2008 To the Citizens of the San Francisco Bay Region and Friends of San Francisco Bay Everywhere: The San Francisco Bay Plan was completed and adopted by the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission in 1968 and submitted to the California Legislature and Governor in January 1969. The Bay Plan was prepared by the Commission over a three-year period pursuant to the McAteer-Petris Act of 1965 which established the Commission as a temporary agency to prepare an enforceable plan to guide the future protection and use of San Francisco Bay and its shoreline. In 1969, the Legislature acted upon the Commission’s recommendations in the Bay Plan and revised the McAteer-Petris Act by designating the Commission as the agency responsible for maintaining and carrying out the provisions of the Act and the Bay Plan for the protection of the Bay and its great natural resources and the development of the Bay and shore- line to their highest potential with a minimum of Bay fill. -

(Oncorhynchus Mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Methods p. 7 Determining Historical Distribution and Current Status; Information Presented in the Report; Table Headings and Terms Defined; Mapping Methods Contra Costa County p. 13 Marsh Creek Watershed; Mt. Diablo Creek Watershed; Walnut Creek Watershed; Rodeo Creek Watershed; Refugio Creek Watershed; Pinole Creek Watershed; Garrity Creek Watershed; San Pablo Creek Watershed; Wildcat Creek Watershed; Cerrito Creek Watershed Contra Costa County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 39 Alameda County p. 45 Codornices Creek Watershed; Strawberry Creek Watershed; Temescal Creek Watershed; Glen Echo Creek Watershed; Sausal Creek Watershed; Peralta Creek Watershed; Lion Creek Watershed; Arroyo Viejo Watershed; San Leandro Creek Watershed; San Lorenzo Creek Watershed; Alameda Creek Watershed; Laguna Creek (Arroyo de la Laguna) Watershed Alameda County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 91 Santa Clara County p. 97 Coyote Creek Watershed; Guadalupe River Watershed; San Tomas Aquino Creek/Saratoga Creek Watershed; Calabazas Creek Watershed; Stevens Creek Watershed; Permanente Creek Watershed; Adobe Creek Watershed; Matadero Creek/Barron Creek Watershed Santa Clara County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. -

Abundance and Distribution of Shorebirds in the San Francisco Bay Area

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 33, Number 2, 2002 ABUNDANCE AND DISTRIBUTION OF SHOREBIRDS IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA LYNNE E. STENZEL, CATHERINE M. HICKEY, JANET E. KJELMYR, and GARY W. PAGE, Point ReyesBird Observatory,4990 ShorelineHighway, Stinson Beach, California 94970 ABSTRACT: On 13 comprehensivecensuses of the San Francisco-SanPablo Bay estuaryand associatedwetlands we counted325,000-396,000 shorebirds (Charadrii)from mid-Augustto mid-September(fall) and in November(early winter), 225,000 from late Januaryto February(late winter); and 589,000-932,000 in late April (spring).Twenty-three of the 38 speciesoccurred on all fall, earlywinter, and springcounts. Median counts in one or moreseasons exceeded 10,000 for 10 of the 23 species,were 1,000-10,000 for 4 of the species,and were less than 1,000 for 9 of the species.On risingtides, while tidal fiats were exposed,those fiats held the majorityof individualsof 12 speciesgroups (encompassing 19 species);salt ponds usuallyheld the majorityof 5 speciesgroups (encompassing 7 species); 1 specieswas primarilyon tidal fiatsand in other wetlandtypes. Most speciesgroups tended to concentratein greaterproportion, relative to the extent of tidal fiat, either in the geographiccenter of the estuaryor in the southernregions of the bay. Shorebirds' densitiesvaried among 14 divisionsof the unvegetatedtidal fiats. Most species groups occurredconsistently in higherdensities in someareas than in others;however, most tidalfiats held relativelyhigh densitiesfor at leastone speciesgroup in at leastone season.Areas supportingthe highesttotal shorebirddensities were also the ones supportinghighest total shorebird biomass, another measure of overallshorebird use. Tidalfiats distinguished most frequenfiy by highdensities or biomasswere on the east sideof centralSan FranciscoBay andadjacent to the activesalt ponds on the eastand southshores of southSan FranciscoBay and alongthe Napa River,which flowsinto San Pablo Bay. -

San Francisco Bay Mercury TMDL Report Mercury TMDL and Evaluate New Card Is in Preparation by the Water and Relevant Information from Board

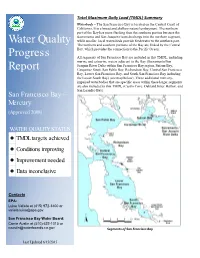

Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Summary Waterbody – The San Francisco Bay is located on the Central Coast of California. It is a broad and shallow natural embayment. The northern part of the Bay has more flushing than the southern portion because the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers discharge into the northern segment, while smaller, local watersheds provide freshwater to the southern part. Water Quality The northern and southern portions of the Bay are linked by the Central Bay, which provides the connection to the Pacific Ocean. Progress All segments of San Francisco Bay are included in this TMDL, including marine and estuarine waters adjacent to the Bay (Sacramento/San Joaquin River Delta within San Francisco Bay region, Suisun Bay, Report Carquinez Strait, San Pablo Bay, Richardson Bay, Central San Francisco Bay, Lower San Francisco Bay, and South San Francisco Bay including the Lower South Bay) (see map below). Three additional mercury- impaired waterbodies that are specific areas within these larger segments are also included in this TMDL (Castro Cove, Oakland Inner Harbor, and San Leandro Bay). San Francisco Bay – Mercury (Approved 2008) WATER QUALITY STATUS ○ TMDL targets achieved ○ Conditions improving ● Improvement needed ○ Data inconclusive Contacts EPA: Luisa Valiela at (415) 972-3400 or [email protected] San Francisco Bay Water Board: Carrie Austin at (510) 622-1015 or [email protected] Segments of San Francisco Bay Last Updated 6/15/2015 Progress Report: Mercury in the San Francisco Bay Water Quality Goals Mercury water quality objectives were identified to protect both people who consume Bay fish and aquatic organisms and wildlife: To protect human health: Not to exceed 0.2 mg mercury per kg (mg/kg) (average wet weight of the edible portion) in trophic level1 (TL) 3 and 4 fish. -

Invasive Spartina Project (Cordgrass)

SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY INVASIVE SPARTINA PROJECT 2612-A 8th Street ● Berkeley ● California 94710 ● (510) 548-2461 Preserving native wetlands PEGGY OLOFSON PROJECT DIRECTOR [email protected] Date: July 1, 2011 INGRID HOGLE MONITORING PROGRAM To: Jennifer Krebs, SFEP MANAGER [email protected] From: Peggy Olofson ERIK GRIJALVA FIELD OPERATIONS MANAGER Subject: Report of Work Completed Under Estuary 2100 Grant #X7-00T04701 [email protected] DREW KERR The State Coastal Conservancy received an Estuary 2100 Grant for $172,325 to use FIELD OPERATIONS ASSISTANT MANAGER for control of non-native invasive Spartina. Conservancy distributed the funds [email protected] through sub-grants to four Invasive Spartina Project (ISP) partners, including Cali- JEN MCBROOM fornia Wildlife Foundation, San Mateo Mosquito Abatement District, Friends of CLAPPER RAIL MONITOR‐ ING MANAGER Corte Madera Creek Watershed, and State Parks and Recreation. These four ISP part- [email protected] ners collectively treated approximately 90 net acres of invasive Spartina for two con- MARILYN LATTA secutive years, furthering the baywide eradication of invasive Spartina restoring and PROJECT MANAGER 510.286.4157 protecting many hundreds of acres of tidal marsh (Figure 1, Table 1). In addition to [email protected] treatment work, the grant funds also provided laboratory analysis of water samples Major Project Funders: collected from treatment sites where herbicide was applied, to confirm that water State Coastal Conser‐ quality was not degraded by the treatments. vancy American Recovery & ISP Partners and contractors conducted treatment work in accordance with Site Spe- Reinvestment Act cific Plans prepared by ISP (Grijalva et al. 2008; National Oceanic & www.spartina.org/project_documents/2008-2010_site_plans_doc_list.htm), and re- Atmospheric Admini‐ stration ported in the 2008-2009 Treatment Report (Grijalva & Kerr, 2011; U.S. -

Oyster Bay Regional Shoreline

7. Birds of Prey End of the Trail Oyster Bay Watch overhead for large, soaring birds. Red-tailed As you close the loop back to the beginning Regional Shoreline hawks, osprey, and northern harriers feed on other of your walk, consider nature’s cycles and your birds, fish, and animals found here. The hunting part in them. From your household and daily grounds of the park are also the nursery area where routines to the natural world, everything is tied SAN LEANDRO these raptors hatch and raise their young. Birds together in this cycle of life. Consider ways you can of prey help keep nature in balance by controlling live more lightly by reducing, reusing, recycling, and East Bay Regional Park District the number of rabbits, squirrels, and other rodents. composting your waste materials. Visit Oyster Bay 2950 Peralta Oaks Court, Oakland, CA 94605 Red-tailed hawk Use binoculars to help identify the species. and the other East Bay Regional Parks often, and 1-888-EBPARKS or 1-888-327-2757 ( TR S 711) Photo: Lenny Carl observe how nature is constantly renewing itself ebparks.org and changing with the seasons. 8. Community Recycling Plant materials from curbside green and food waste The programs in Alameda and Contra Costa counties Not to Scale Undergoing are transferred here. This is where your green SF Bay Trail/ Bill Lockyer Construction waste bin materials are transformed into Bridge Davis St. Doolittle Dr. Doolittle an energy source or useful soil product! Recreational Oyster Bay improvement Slow and relentless, nature decomposes and Regional 880 plans for Shoreline restores nutrients to the earth. -

PUBLIC REVIEW DRAFT Union Pacific Railroad Oakland

PUBLIC REVIEW DRAFT Union Pacifi c Railroad Oakland Subdivision Corridor Improvement Study Executive Summary For the: Alameda County Public Works Agency Prepared by: Alta Planning + Design In Partnership with: HDR Engineering, Inc. and LSA Associates November 2009 Funded by: Alameda County Public Works Agency Alameda County Transportation Improvement Authority City of San Leandro The Union Pacific Railroad Oakland Subdivision Corridor Improvement Study A Feasibility Study Analyzing the Potential for a Multi-Use Pathway Following the Oakland Subdivision Including On-Street, Rail-With-Trail and Rail-To-Trail Alternatives Alameda County Public Works Agency Prepared by: Alta Planning + Design, Inc. In Partnership with: HDR Engineering, Inc. LSA Associates November 2009 Acknowledgements Alameda County Board of Supervisors Scott Haggerty, District 1 Gail Steele, District 2 Alice Lai-Bitker, President, District 3 Nate Miley, Vice-President, District 4 Keith Carson, District 5 Director of Alameda County Public Works Agency Daniel Woldesenbet, Ph.D., P.E. Technical Advisory Committee Paul Keener, Alameda County Public Works Agency Rochelle Wheeler, Alameda County Transportation Improvement Authority Keith Cooke, City of San Leandro Reh-Lin Chen, City of San Leandro Mark Evanoff, City of Union City Joan Malloy, City of Union City Don Frascinella, City of Hayward Jason Patton, City of Oakland David Ralston, City of Oakland Jay Musante, City of Oakland Tim Chan, BART Planning Sue Shaffer, BART Real Estate Thomas Tumola, BART Planning Jim Allison, Capital Corridor Joint Powers Authority Katherine Melcher, Urban Ecology Diane Stark, Alameda County Congestion Management Agency Supporting Agencies Alameda County Transportation Improvement Authority Alameda County Congestion Management Agency East Bay Regional Park District Metropolitan Transportation Commission Alameda County Staff Paul J. -

Multi-Year Synthesis with a Focus on Pcbs and Hg

CLEAN WATER / RMP NUMBER 773 DECEMBER 2015 Sources, Pathways and Loadings: Multi-Year Synthesis with a Focus on PCBs and Hg Prepared by Lester J. McKee, Alicia N. Gilbreath, Jennifer A. Hunt, Jing Wu, and Don Yee San Francisco Estuary Institute, Richmond, California On December 15, 2015 For Regional Monitoring Program for Water Quality in San Francisco Bay (RMP) Sources Pathways and Loadings Workgroup (SPLWG) Small Tributaries Loading Strategy (STLS) SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY INSTITUTE | AQUATIC SCIENCE CENTER 4911 Central Avenue, Richmond, CA 94804 • p: 510-746-7334 (SFEI) • f: 510-746-7300 • www.sfei.org THIS REPORT SHOULD BE CITED AS: McKee, L.J. Gilbreath, N., Hunt, J.A., Wu, J., and Yee, D., 2015. Sources, Pathways and Loadings: Multi-Year Synthesis with a Focus on PCBs and Hg. A technical report prepared for the Regional Monitoring Program for Water Quality in San Francisco Bay (RMP), Sources, Pathways and Loadings Workgroup (SPLWG), Small Tributaries Loading Strategy (STLS). SFEI Contribution No. 773. San Francisco Estuary Institute, Richmond, CA. Final Report Executive Summary This report provides a synthesis of information gathered since 2000 on sources, pathways, and loadings of pollutants of concern in the San Francisco Bay Area with a focus on polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and total mercury (Hg). Concentration and load estimates for other pollutants of concern (POC) are provided in the Appendix tables but not supported by any synthesis or discussion in the main body of the report. The PCB and Hg TMDLs for San Francisco Bay call for implementation of control measures to reduce stormwater PCB loads from 20 kg to 2 kg by 2030 and to reduce stormwater Hg loads from 160 kg to 80 kg by 2028 with an interim milestone of 120 kg by 2018. -

Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (Pfass) in San Francisco Bay: Synthesis and Strategy

CONTRIBUTION NO. 867 JUNE 2018 Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in San Francisco Bay: Synthesis and Strategy Prepared by Meg Sedlak, Rebecca Sutton, Adam Wong, and Diana Lin San Francisco Estuary Institute SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY INSTITUTE • CLEAN WATER PROGRAM/RMP • 4911 CENTRAL AVE., RICHMOND, CA • WWW.SFEI.ORG Suggested citation: Sedlak, M., Sutton R., Wong A., Lin, Diana. 2018. Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in San Francisco Bay: Synthesis and Strategy. RMP Contribution No. 867. San Francisco Estuary Institute, Richmond CA. 130 pages. FINAL JUNE 2018 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 Introduction and Overview of PFAS Chemistry, Uses, Concerns and Management ........................ 4 1.1 Objectives of this Report............................................................................................................... 4 1.2 PFASs: Structure and Uses ............................................................................................................ 4 1.2.1 Perfluoroalkyl Substances ..................................................................................................... 5 1.2.2 Polyfluoroalkyl Substances ................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Uses of PFASs ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.4