Artnerships for the Sustainable Development of Cities in the APEC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reformation of Mass Transportation System in Seoul Metropolitan Area

Reformation of Mass Transportation System in Seoul Metropolitan Area 2013. 11. Presenter : Dr. Sang Keon Lee Co-author: Dr. Sang Min Lee(KOTI) General Information Seoul (Area=605㎢, 10mill. 23.5%) - Population of South Korea : 51.8 Million (‘13) Capital Region (Area=11,730㎢, 25mill. 49.4%)- Size of South Korea : 99,990.5 ㎢ - South Korean Capital : Seoul 2 Ⅰ. Major changes of recent decades in Korea Korea’s Pathways at a glance 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s Economic Economic Heavy-Chem. Stabilization-Growth- Economic Crisis & Post-war recovery Development takeoff Industry drive Balancing-Deregulation Restructuring Development of Balanced Territorial Post-war Growth pole Regional growth Promotion Industrialization regional Development reconstruction development Limit on urban growth base development Post-war Construction of Highways & National strategic networks Environ. friendly Transport reconstruction industrial railways Urban subway / New technology 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Population 20,189 24,989 31,435 37,407 43,390 45,985 48,580 (1,000 pop.) GDP - 1,154 1,994 3,358 6,895 11,347 16,372 ($) No. Cars - - 127 528 3,395 12,059 17,941 (1,000 cars) Length of 25,683 27,169 40,244 46,950 56,715 88,775 105,565 Road(km) 3 Population and Size - Seoul-Metropoliotan Area · Regions : Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi · Radius : Seoul City 11~16 km Metro Seoul 4872 km Population Size Density (million) (㎢) (per ㎢) Seoul 10.36 605.3 17,115 Incheon 2.66 1,002.1 2,654 Gyeonggi 11.11 10,183.3 1,091 Total 24.13 11,790.7 2,047 4 III. -

Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-Do & Seoul Metropolitan Area

Gyeongchun line Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-do & Seoul Metropolitan Area Hoeryong Uijeongbu Ganeung Nogyang Yangju Deokgye Deokjeong Jihaeng DongducheonBosan Jungang DongducheonSoyosan Chuncheon Mangwolsa 1 Starting Point Destination Dobongsan 7 Namchuncheon Jangam Dobong Suraksan Gimyujeong Musan Paju Wollong GeumchonGeumneungUnjeong TanhyeonIlsan Banghak Madeul Sanggye Danngogae Gyeongui line Pungsan Gireum Nowon 4 Gangchon 6 Sungshin Baengma Mia Women’s Univ. Suyu Nokcheon Junggye Changdong Baekgyang-ri Dokbawi Ssangmun Goksan Miasamgeori Wolgye Hagye Daehwa Juyeop Jeongbalsan Madu Baekseok Hwajeong Wondang Samsong Jichuk Gupabal Yeonsinnae Bulgwang Nokbeon Hongje Muakjae Hansung Univ. Kwangwoon Gulbongsan Univ. Gongneung 3 Dongnimmun Hwarangdae Bonghwasan Sinnae (not open) Daegok Anam Korea Univ. Wolgok Sangwolgok Dolgoji Taereung Bomun 6 Hangang River Gusan Yeokchon Gyeongbokgung Seokgye Gapyeong Neunggok Hyehwa Sinmun Meokgol Airport line Eungam Anguk Changsin Jongno Hankuk Univ. Junghwa 9 5 of Foreign Studies Haengsin Gwanghwamun 3(sam)-ga Jongno 5(o)-gu Sinseol-dong Jegi-dong Cheongnyangni Incheon Saejeol Int’l Airport Galmae Byeollae Sareung Maseok Dongdaemun Dongmyo Sangbong Toegyewon Geumgok Pyeongnae Sangcheon Banghwa Hoegi Mangu Hopyeong Daeseong-ri Hwajeon Jonggak Yongdu Cheong Pyeong Incheon Int’l Airport Jeungsan Myeonmok Seodaemun Cargo Terminal Gaehwa Gaehwasan Susaek Digital Media City Sindap Gajwa Sagajeong Dongdaemun Guri Sinchon Dosim Unseo Ahyeon Euljiro Euljiro Euljiro History&Culture Park Donong Deokso Paldang Ungilsan Yangsu Chungjeongno City Hall 3(sa)-ga 3(sa)-ga Yangwon Yangjeong World Cup 4(sa)-ga Sindang Yongmasan Gyeyang Gimpo Int’l Airport Stadium Sinwon Airprot Market Sinbanghwa Ewha Womans Geomam Univ. Sangwangsimni Magoknaru Junggok Hangang River Mapo-gu Sinchon Aeogae Dapsimni Songjeong Office Chungmuro Gunja Guksu Seoul Station Cheonggu 5 Yangcheon Hongik Univ. -

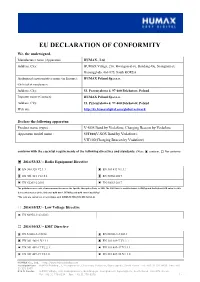

EC Declaration of Conformity

EU DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY We, the undersigned, Manufacturer name (Apparatus) HUMAX., Ltd Address, City: HUMAX Village, 216, Hwangsaeul-ro, Bundang-Gu, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, 463-875, South KOREA Authorized representative name (in Europe): HUMAX Poland Sp.z.o.o. (On behalf of manufacturer) Address, City: Ul. Przemyslowa 4, 97-400 Belchatow, Poland Importer name (Contact): HUMAX Poland Sp.z.o.o. Address, City: Ul. Przemyslowa 4, 97-400 Belchatow, Poland Web site http://kr.humaxdigital.com/global-network Declare the following apparatus: Product name (type) : V-SOS Band by Vodafone, Charging Beacon by Vodafone Apparatus model name : VIT100(V-SOS Band by Vodafone), VIT100(Charging Beacon by Vodafone) conform with the essential requirements of the following directives and standards: (Note: ▣ conform, □ Not conform) ▣ 2014/53/EU - Radio Equipment Directive ▣ EN 300 328 V2.1.1 ▣ EN 303 413 V1.1.1 ▣ EN 301 511 V12.5.1 ▣ EN 50566:2017 ▣ EN 62209-2:2010 ▣ EN 50663:2017 The guidelines use a unit of measurement known as the Specific Absorption Rate, or SAR. The SAR limit for mobile devices is 4W/kg and the highest SAR value for this device when tested at the limb was GSM 900 1.567W/kg and GSM 1800 1.922W/kg*. *The tests are carried out in accordance with [CENELEC EN50566] [IEC 62209-2]. □ 2014/35/EU - Low Voltage Directive ▣ EN 60950-1/A2:2013 □ 2014/30/EU - EMC Directive ▣ EN 61000-3-2:2014 ▣ EN 61000-3-3:2013 ▣ EN 301 489-1 V2.1.1 ▣ EN 301 489-7 V1.3.1 ▣ EN 301 489-17 V2.2.1 ▣ EN 301 489-17 V3.1.1 ▣ EN 301 489-19 V2.1.0 ▣ EN 301 489-52 V1.1.0 HUMAX Co., Ltd. -

Seoul Cities

Cities 29 (2012) 142–154 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cities journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cities City profile Seoul ⇑ Hyung Min Kim, Sun Sheng Han Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC 3010, Australia article info abstract Article history: Seoul is a major global city with a history of over 600 years. Its development trajectory, current status in Received 13 August 2010 the world economy, and challenges faced in socio-spatial dynamics present an excellent case in the study Received in revised form 25 November 2010 of cities, especially of the Asia–Pacific region. This profile outlines Seoul’s historical development, recent Accepted 12 February 2011 changes and contemporary conditions (in terms of its territory, economy, land and housing market, Available online 13 July 2011 urbanisation policy, infrastructure development, social impact and culture), metropolitan planning, and future development. Keywords: Ó 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Urban history Economic development Housing Planning policies Metropolitan governance Historical development structure of cities, were adopted as fundamental to the Chosun Dynasty (Kim, 2009). Thus, in line with feng shui and Confucian A significant year in Seoul’s history is 1394 during which Seoul, by principles, the Kyongbok Palace was located in the middle of the the name of Han Yang, was chosen as the new capital of the Chosun (or city2; the ancestor shrine Chongmyo in the east of the Palace, and Joseon) Dynasty (Kim, 2009: p. 194). The first 10 years of Seoul as a the Dynasty Sajic in the west3 (Ko, 2005). The city wall was built capital city were characterised by uncertainty about its status as along the four inner mountains (Fig. -

How IT Preparedness Helped to Create a Digital Field Hospital to Care For

www.nature.com/npjdigitalmed PERSPECTIVE OPEN How IT preparedness helped to create a digital field hospital to care for COVID-19 patients in S. Korea ✉ Se Young Jung1,2, Ho-Young Lee 1,3 , Hee Hwang1,4, Keehyuck Lee1,2 and Rong-min Baek5 npj Digital Medicine (2020) 3:157 ; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-00366-4 CORONAVIRUS DISEASE 2019 (COVID-19) OUTBREAK IT preparedness of SNUBH helped create a digital field hospital to IN S. KOREA manage COVID-19 South Korea has overseen one of the worst COVID-19 outbreaks When developing an unprecedented medical system, it is essential outside China with over 8162 confirmed cases reported by 15 to design the system with the fewest resources, with as little March 2020. The government succeeded in curbing the spread of damage to the current medical system as possible. SNUBH’sIT the disease until mid-February. However, the number of confirmed preparedness made it possible to create a fully functional “digital cases exponentially increased since mid-February, when the field hospital” in a short time without wasting medical resources. number of cases increased because of a secretive religious When designing a CTC as a digital hospital with only a few medical organization in Daegu, changing the strategy from containment staff on-site, we took three important considerations into account. to mitigation of COVID-19, as the government failed to prevent First, we minimized direct contact with the patient. Second, all information was recorded electronically and incorporated into mass infection via intensive quarantine and extensive epidemio- 1234567890():,; electronic health records (EHRs). -

Games Schedule 7Th Asia Pacific Deaf Games Seoul, Korea

Games Schedule 7th Asia Pacific Deaf Games Seoul, Korea May June Sport Venue 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 Seoul Olympic Main T G G G Stadium 1 ATHLETICS Seoul Olympic T G G Secondary Stadium Tancheon Secondary T 2 BASEBALL G G Stadium G Namyangju 3 BADMINTON T G G G G Gymnasium 4 BASKETBALL Dongseoul College T G G G G Tancheon Bowling 5 BOWLING T G G G G G Alley T 6 CYCLING Olympic Park G G G G Namyangju Sports T G R G R G G G R G Complex 7 FOOTBALL Seoul Olympic G G Secondary Stadium 8 FUTSAL SK Handball Stadium T G G Korea Armed Forces 9 JUDO Athletic Corps T G G Gymnasium Korea National Sport T T University 10 SWIMMING Seoul Physical High G G G G School 11 TABLE TENNIS Jamsil Gymnasium T G G G G 12 TAEKWONDO Dongseoul College T G 13 TENNIS Olympic Park T G G Samsung Training 14 VOLLEYBALL T G G G Center T: Training G: Games R: Rest Page 1 of 1 Venues 7th Asia Pacific Deaf Games Seoul, Korea Sport Venue Address Seoul Olympic Main 10, Jamsil-dong, Songpa-gu, Seoul, Korea Stadium 1 ATHLETICS Seoul Olympic 10, Jamsil-dong, Songpa-gu, Seoul, Korea Secondary Stadium Tancheon Secondary 486, Yatap-dong, Bundang-gu, 2 BASEBALL Stadium Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea Namyangju 3 BADMINTON San 95, Ipae-dong, Namyangju-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea Gymnasium 76, Bokjeong-ro, Sujeong-gu, Seongnam-si, 4 BASKETBALL Dongseoul College Gyeonggi-do, Korea Tancheon Bowling 486, Yatap-dong, Bundang-gu, 5 BOWLING Alley Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea 6 CYCLING Olympic Park 88, Bangi-dong, Songpa-gu, Seoul, Korea Namyangju Sports San 95, Ipae-dong, Namyangju-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea Complex 7 FOOTBALL Seoul Olympic 10, Jamsil-dong, Songpa-gu, Seoul, Korea Secondary Stadium 8 FUTSAL SK Handball Stadium 88-2, Bangi-dong, Songpa-gu, Seoul, Korea Korea Armed Forces 122-16, Changgok-dong, Sujeong-gu, Seongnam-si, 9 JUDO Athletic Corps Gyeonggi-do, Korea Gymnasium Korea National Sport Korean National Univ. -

English Program in Korea (EPIK) National Institute for International Education (NIIED) Ministry of Education (MOE)

English Program In Korea (EPIK) National Institute for International Education (NIIED) Ministry of Education (MOE) #191, Jeongjail-ro, Bundang-gu, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, 13557, Republic of Korea. Website: www.epik.go.kr April 2016 EPIK Orientation Information 1. Overview PURPOSE l To enhance the understanding of teaching English as a foreign language in Korea, including various teaching methodologies as well as Korean culture and history. l To enhance understanding of the teaching environment in Korean public schools and life in Korea which will help facilitate adaptation to life in Korea and in the Korean school system. l To provide participants an opportunity to share their ideas and insights about teaching English and living in Korea. TRAINING INFORMATION l Date: From Thursday, April 21st to Tuesday, April 26th, 2016 (5 Nights 6 Days) *Registration : April 21 (Thu) 12:00~15:00 l Venue: The National Institute for International Education (NIIED) - Main Building & Dormitory -Address: 국립국제교육원(NIIED) #191, Jeongjail-ro, Bundang-gu, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, 13557, -주소: (우)13557 경기도 성남시 분당구 정자일로 191 l Participants: 90 Guest English Teachers (GETs) 2. Orientation Venue (NIIED, Gyeonggi) REGISTRATION st l Registration will be held at the NIIED on Thursday, April 21 between 12:00pm to 3:00pm in the lobby(1F) TRANSIT OPTION #1 – AIRPORT BUS #5400 l Limousine bus departing From Incheon Airport to Dankook University l Bus Boarding Area: 8A (1st Floor) l Fare: Approximately 12,000 KRW l Departure Intervals: Every 20-30 Minutes l Estimated Transit Time: Approximately 1 Hour 30 Minutes l Bus Stop to Disembarkment: Jeongja Station(정자역) l Walk to the NIIED (Approx. -

Supplementary Information For

Supplementary Information for Article PI3K p110α Blockade Enhances Anti-Tumor Efficacy of Abemaciclib in Human Colorectal Cancer Cells Hyun Jung Lee 1,2,†, Kui-Jin Kim 3,4,†, Ji Hea Sung 3, Milang Nam 3, Koung Jin Suh 3, Ji-Won Kim 3, Se Hyun Kim 3, Jin Won Kim 3, Yu Jung Kim 3, Keun-Wook Lee 1,3, Jong Seok Lee 1,3 and Jee Hyun Kim 1,3,* 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, 03080, Republic of Korea; [email protected] (H.J.L.); [email protected] (K.W.L.); [email protected] (J.S.L.); [email protected] (J.H.K) 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, 10326, Republic of Korea 3 Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seongnam, 13620, Republic of Korea; [email protected] (K.J.K.); [email protected] (J.H.S.); [email protected] (M.L.N); [email protected] (S.H.K.); [email protected] (K.J.S.); [email protected] (J.W.K.); [email protected] (J.W.K.); [email protected] (Y.J.K.); [email protected] (K.W.L.); [email protected] (J.S.L.); [email protected] (J.H.K) 4 Biomedical Research Institute, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, 13620, Republic of Korea; [email protected] (K.J.K) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel: +82-31-787-7022 Fax: +82-31-787-4052 † These authors have contributed equally to this work. -

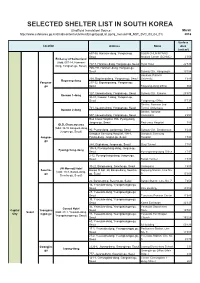

Selected Shelter List in South Korea

SELECTED SHELTER LIST IN SOUTH KOREA (Unofficial translation/ Source : March http://www.safekorea.go.kr/dmtd/contents/civil/est/EmgnEqupList.jsp?q_menuid=M_NST_SVC_03_04_01) 2016 Surface Location Address Name Area SOON CHUN HYANG Medical Center, (unit:m²) 657-58, Hannam-dong, Yongsan-gu, SOON CHUN HYANG Seoul Medical Center (SCHMC) 2'056 Embassy of Switzerland (Add: 657-14, Hannam- 747-7, Hannam-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Hyatt Hotel 22'539 dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul) 726-494, Hannam-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Subway Stn. Hangangjin 10'794 Hankook Politech 238, Bogwang-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul University 1'643 Bogwang-dong Yongsan- 217-32, Bigwang-dong, Yongsan-gu, gu Seoul Bogwang-dong Office 660 127, Itaewon-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Subway Stn. Itaewon 25'572 Itaewon 1-dong 34-87, Itaewon 1-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Yongsan-gu Office 17'737 Shelter, Namsan 2nd 721, Itaewon-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Tunnel Underpass 439 Itaewon 2-dong Shelter, Itaewon 507, Itaewon-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul Underpass 2'294 Red Cross Hospital, 956, Pyung-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul Red cross Hospital 789 OLD_Chancery area (Add: 32-10 Songwol-dong, 90, Pyung-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul Subway Stn. Seodaemun 9'244 Jongno-gu, Seoul) Gangbuk Samsung Hospital, 108-1, Gangbuk Samsung Jongno- Pyung-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul Hospital 1'598 gu 244, Gugi-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul Gugi Tunnel 1'781 186-9, Pyeongchang-dong, Jongno-gu, Pyeongchang-dong Seoul Pyeongchang-dong Office 1'797 2-12, Pyeongchang-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul Bukak Tunnel 1'838 30-22, Banpo-dong, Seocho-gu, Seoul Underpass 1'400 JW Marriott Hotel Seocho- Banpo Xi Apt, 20, Banpo-dong, Seocho- Sapyung Station, Line No. -

Venue Information Venue: TTA (Telecommunications Technology Association)

GENERAL INFORMATION Venue Information Venue: TTA (Telecommunications Technology Association) Address: 47, Bundang-ro, Bundang-gu, Seongmam-si, Gyeonggi-do, 463-824, Korea. Home page: http://www.tta.or.kr/English/ Transfers from Airport #1 (Using Airport Bus) TTA is located in the downtown area and the center of Seongnam-City, approximately one hour from Airport. Please refer following website for airport transportation information. Incheon Airport (http://www.airport.kr/airport/traffic/bus/busList.iia?flag=E&fake=1306823313914) In order to ensure smooth access from Incheon International Airport to TTA, we are pleased to provide some practical information. 1. Arrival at Incheon International Airport When you’re arrived at the airport, please pick up some useful information, e.g., City Maps, Tourist Information booklet at Information Center located inside of the airport building, please see the right picture. 2. At near to Exit Number #8, you can buy the Ticket for Airport Limousine Bus from the Airport to Bundang (or Seohyeon Station), the fare is 12,000 Won. Please also see the right picture. ※ Please Note that TAXI (from the Airport to TTA or downtown) is not recommended due to high cost. (over 70,000Won for Normal Taxi /120,000Won for Deluxe Taxi) 3. If you are sure to get the Ticket, then you can move to Airport Limousine BUS STOP #8A with getting out the Airport building through the Exit Number #7. 4. As soon as you’re getting out from the Airport Building, you can find the bus to Bundang (bus number is 5400) at the Bus Stop #8A. -

S E O U L National University Bundang Hospital Clinical

SEOUL NATIONAL UNIVERSITY BUNDANG HOSPITAL CLINICAL TRIALS CENTER Contact Us Seoul National University Bundang Hospital Clinical Trials Center 82, Gumi-ro 173 Beon-gil, Bundang-gu, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do 463-707, South Korea Tel : 82-31-787-3941~2 E-mail : [email protected] We appreciate your interest in our center. About Us Seoul National University Bundang Hospital Clinical TRIALS CENTER CLINICAL UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL BUNDANG SEOUL NATIONAL Trials Center is an state-of-the-art academic clinical re- search center of excellence with full-service operational capabilities. We aims to provide the best research en- vironment for investigators, sponsors and participants under the first digital general hospital in Korea. Mission and Vision Advancing medical research and treatment for patients through providing a state-of-the-art center for ethical, scientific, and efficient clinical trials SEOUL NATIONAL Vision UNIVERSITY · Best quality and reliability for clinical trials BUNDANG HOSPITAL · Best model for industry-academia-research network · Best technology for conducting advanced CLINICAL TRIALS CENTER researches · Global leading center for geriatric clinical trials About Us SEOUL NATIONAL UNIVERSITY BUNDANG HOSPITAL CLINICAL TRIALS CENTER CLINICAL UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL BUNDANG SEOUL NATIONAL SNUBH Overview Organization Clinical Trial Center Clinical Trial Center Center for l Open in March, 2003 Pharmaceutical Research Center for l First full digital general hospital in Korea Biomedical Research Institute Center for Pharmaceutical Research l First -

PANGYO OFFICE MARKET AFTER COVID-19 Korea's Silicon Valley Pangyo Office Market Expands Despite Covid-19 COLLIERS RADAR OFFICE | RESEARCH | SEOUL | 13 AUGUST 2020

COLLIERS RADAR OFFICE | RESEARCH | SEOUL | 13 AUGUST 2020 Judy Jang Associate Director | Research | Korea +822 6325 1918 [email protected] Robert Wilkinson Managing Director | Korea +82 2 6325 1901 [email protected] PANGYO OFFICE MARKET AFTER COVID-19 Korea's Silicon Valley Pangyo Office Market expands despite Covid-19 COLLIERS RADAR OFFICE | RESEARCH | SEOUL | 13 AUGUST 2020 Summary & Recommendations Pangyo, located 10km South east from Gangnam area in Seoul, is one of the new cities developed by the Korean government. It is known as a convenient location as it is at the crossing of the Gyeongbu The Pangyo market has gained attention Expressway and Seoul Ring Expressway. The government developed the area to foster advanced from building owners, investors, and industries. Pangyo 1st Techno Valley is a 66-hectare development at Bundang-gu in Seongnam-si, and tenants as Pangyo 1st Techno Valley and Pangyo 2nd and 3rd Techno Valleys are under construction following the success of Pangyo 1st Techno Pangyo Alpha Dome City have seen their Valley. The market in the Pangyo area is scheduled to expand as Pangyo 2nd and 3rd Techno Valleys occupancy stabilize and the resale market are under development. has been deregulated in 2020. When Unlike Seoul’s three existing major office submarkets, where leasing activities have slowed down due Pangyo 2nd is completed in 2022 and 3rd to the Covid-19, the Pangyo Office market saw the lease Covid-19 impact as IT tenants continued Techno Valley is established in 2025, we active leasing. expect Pangyo will emerge as a major When Pangyo1st Techno Valley was under construction, many companies moved from the Gangnam office submarket to rival Seoul’s existing area to Pangyo due to tax benefits and financial support.