Lawrence (Larry) “Harbottle” Kamakawiwoole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaiian Historical Society

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY PAPERS OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY NUMBER 17 PAPERS READ BEFORE THE SOCIETY SEPTEMBER 30, 1930 PAPERS OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY NUMBER 17 PAPERS READ BEFORE THE SOCIETY , SEPTEMBER 30, 1930 Printed by The Printshop Co., Ltd. 1930 CONTENTS Page Proceedings of the Hawaiian Historical Society Meeting, September 30, 1930 _.. 5 Historical Notes- 7 By Albert Pierce Taylor, Secretary Reminiscences of the Court of Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma 17 By Col. Curtis Piehu Iaukea former Chamberlain to King Kalakaua The Adoption of the Hawaiian Alphabet 28 By Col. Thomas Marshall Spaulding, U.S.A. The Burial Caves- of Pahukaina 34 By Emma Ahuena Davis on Taylor Annexation Scheme of 1854 That Failed: Chapter Eighteen —Life of Admiral Theodoras Bailey, U.S.N ,.. 39 By Francis R. Stoddard «f (Read by Albert Pierce Taylor) - • . • Kauai Archeology 53 By Wendell C. Bennett Read before Kauai Historical Society, May 20, 1929 Burial of King Keawe '.. 63 By John P. G. Stokes PROCEEDINGS OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY MEETING SEPTEMBER 30, 1930 Meeting of the Society was called for this date, at 7:30 P. M., in the Library of Hawaii, to hear several Papers which were prepared by members on varied historical phases relating to the Hawaiian Islands. Bishop H. B. Restarick, president, in the chair; A. P. Taylor, secretary and several of the trustees, more members than usual in attendance, and many visitors present, the assembly room being filled to capacity. Bishop Restarick announced that the names of Harold W. Bradley, of Pomona, Calif., engaged in historical research in Honolulu until recently, and Bishop S. -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H. -

Center for Hawaiian Sovereignty Studies 46-255 Kahuhipa St. Suite 1205 Kane'ohe, HI 96744 (808) 247-7942 Kenneth R

Center for Hawaiian Sovereignty Studies 46-255 Kahuhipa St. Suite 1205 Kane'ohe, HI 96744 (808) 247-7942 Kenneth R. Conklin, Ph.D. Executive Director e-mail [email protected] Unity, Equality, Aloha for all To: HOUSE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION For hearing Thursday, March 18, 2021 Re: HCR179, HR148 URGING THE SUPERINTENDENT OF EDUCATION TO REQUEST THE BOARD OF EDUCATION TO CHANGE THE NAME OF PRESIDENT WILLIAM MCKINLEY HIGH SCHOOL BACK TO THE SCHOOL'S PREVIOUS NAME OF HONOLULU HIGH SCHOOL AND TO REMOVE THE STATUE OF PRESIDENT MCKINLEY FROM THE SCHOOL PREMISES TESTIMONY IN OPPOSITION There is only one reason why some activists want to abolish "McKinley" from the name of the school and remove his statue from the campus. The reason is, they want to rip the 50th star off the American flag and return Hawaii to its former status as an independent nation. And through this resolution they want to enlist you legislators as collaborators in their treasonous propaganda campaign. The strongest evidence that this is their motive is easy to see in the "whereas" clauses of this resolution and in documents provided by the NEA and the HSTA which are filled with historical falsehoods trashing the alleged U.S. "invasion" and "occupation" of Hawaii; alleged HCR179, HR148 Page !1 of !10 Conklin HSE EDN 031821 suppression of Hawaiian language and culture; and civics curriculum in the early Territorial period. Portraying Native Hawaiians as victims of colonial oppression and/or belligerent military occupation is designed to bolster demands to "give Hawaii back to the Hawaiians", thereby producing a race-supremacist government and turning the other 80% of Hawaii's people into second-class citizens. -

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project by Gary T. Kubota Copyright © 2018, Stories of Change – Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project The Kokua Hawaii Oral History interviews are the property of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project, and are published with the permission of the interviewees for scholarly and educational purposes as determined by Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. This material shall not be used for commercial purposes without the express written consent of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. With brief quotations and proper attribution, and other uses as permitted under U.S. copyright law are allowed. Otherwise, all rights are reserved. For permission to reproduce any content, please contact Gary T. Kubota at [email protected] or Lawrence Kamakawiwoole at [email protected]. Cover photo: The cover photograph was taken by Ed Greevy at the Hawaii State Capitol in 1971. ISBN 978-0-9799467-2-1 Table of Contents Foreword by Larry Kamakawiwoole ................................... 3 George Cooper. 5 Gov. John Waihee. 9 Edwina Moanikeala Akaka ......................................... 18 Raymond Catania ................................................ 29 Lori Treschuk. 46 Mary Whang Choy ............................................... 52 Clyde Maurice Kalani Ohelo ........................................ 67 Wallace Fukunaga .............................................. -

Hawaiian Mission Children Named After Ali'ì

Hawaiian Mission Children Named After Ali‘ì “I was born in the ‘Old Mission House’ in Honolulu on the 5th day of July, 1831. When I was but a few hours old, ‘Kīna’u,’ the Premier, came into the bedroom with her crowd of ‘kahus,’ took me into her arms and said that she wanted to adopt me, as she had no girl of her own.” “My mother, in her weak state, was terribly agitated, knowing that the missionaries were unpopular and entirely dependent on the good-will of the natives, so feared the consequences of a denial. They sent for my father in haste, who took in the state of affairs at a glance.” “’We don’t give away our children,’ he said to Kīna’u. ‘But you are poor, I am rich, I give you much money,’ replied the Chiefess. ‘No, you can’t have her,’ my father answered firmly. Kīna’u tossed me angrily down on the bed and walked away, leaving my poor mother in a very anxious frame of mind.” (Wilder; Wight) “She accordingly went away in an angry and sullen mood, and was not heard from until the infant was being christened a few weeks later, when she again appeared, elbowed the father to one side, and exclaimed in the haughtiest of tones, ‘Call the little baby Kīna’u.’” “Fearing that a second refusal would result disastrously, the parents agreed, and the child was accordingly christened Elizabeth Kīna’u Judd.” (The Friend, May 1912) Kīna’u “seemed somewhat appeased after the (christening) ceremony, and, as I was the first white girl she had ever seen, deigned from that time on to show a great interest in me, either visiting me or having me visit her every day.” (Wright, Wight) Kīna’u, daughter of Kamehameha I, became a Christian in 1830. -

City and County of Honolulu

CITY AND COUNTY OF HONOLULU Elderly Affairs Division Department of Community Services FOUR-YEAR AREA PLAN ON AGING October 1, 2007- September 30, 2011 for the As the Planning Service Area in the State of Hawaii (revised 09/15/09) 715 South King Street, Suite 200 Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Phone: (808) 768-7705 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Verification of Intent 4 Executive Summary 5 Introduction A. Orientation to AAA Plan 7 B. An Overview of the Aging Network 8 C. AAA Planning Process 17 Part I. Overview of the Older Adult Population, Existing Programs and Services, and Unmet Needs A. Overview of the Older Adult Population 1. Honolulu’s Population Profile 21 2. Issues and Areas of Concern 50 B. Description of Existing Programs and Services 1. Existing Programs and Services 59 2. Maps of Community Focal Points, 123 Multi-Purpose Senior Centers and Nutrition Sites 3. Community Focal Points and Multi-Purpose 124 Senior Centers 4. Congregate Nutrition Sites and Home 127 Delivered Distribution Centers 5. Acute, Long-Term Care Institutional and Facility Care 142 C. Unmet Needs 155 Part II: Recommendations A. Framework 160 B. Prioritization of Needs and Issues 162 C. Strategies to Meet Issues 163 Part III: Action Plans A. Summary of Goals 167 B. Summary of Objectives 168 C. Objectives and Action Plans 172 2 D. Targeting Services 1. The Next Four Years 207 2. The Previous Year: FY 2006 211 E. Waivers 1. Waiver to Provide Direct Service(s) 219 2. Waiver of Priority Categories of Services 220 Part IV: Funding Plans A. -

History of Ko`Olaupoko

Appendix D: Historical Data related to Ko`olaupoko HISTORY OF KO`OLAUPOKO The first Polynesians arrived in Hawai`i sometime around the 5th century A.D., sailing thousands of miles across the vast Pacific Ocean, from the southwestern regions where Tahiti, New Zealand, and the Society Islands reside. They were seasoned, experienced sailors with a wealth of knowledge of the winds, the ocean currents and the heavens. With no form of written language, all of their experiences were remembered and passed on to the following generations orally, sometimes through songs (mele), dances (hula), or chants (oli). It is uncertain as to when these first peoples eventually settled on the windward side of O`ahu (east O`ahu), but archaeological evidence confirms their existence in the 13th century A.D. The windward side of O`ahu is made up of two districts: Ko`olauloa (long Ko`olau) to the north, and Ko`olaupoko (short Ko`olau) to the south. These districts are bordered on the west by the entire ridge of the Ko`olau Mountain range. Within each district are several land divisions called ahupua`a, which extend from the mountain ridges to beyond the reefs offshore. The land was divided this way so that families could have access to the provisions of both the land (`aina) and the sea (kai). Ko`olaupoko, that region which encompasses Kane`ohe Bay, is divided into nine ahupua`a, with Kualoa being the northernmost (and smallest), and Kane`ohe being the southernmost (and largest). From north to south the nine ahupua`a are Kualoa, Hakipu`u, Waikane, Waiahole, Ka`alaea, Waihe`e, Kahalu`u, He`eia, and Kane`ohe. -

MAP: Hawaii Public Schools

KAUAI HAWAII U A H I I N KAUAI W PUBLIC SCHOOLS L A I T R N C E N D DISTRICT L W E E A W R A D R D H O N O L U L U OAHU MOLOKAI L A N A I U I M A MAUI DISTRICT HAWAII HAWAII DISTRICT RS 21-0193, August 2020 (Rev. of RS 16-0576) HAWAII PUBLIC SCHOOLS Honolulu District H l Elementary School O N O pl Elementary & Intermediate School L U L U p OAHU Intermediate/Middle School np Intermediate & High School n High School Kalihi E pl Kaewai E n Elementary/Intermediate & High School l Kalihi Uka E * Special School ll Dole M H p Linapuni E Nuuanu E l Maemae E O lll Kapalama E l n Lanakila E N l p l Kauluwela E l ll Kawananakoa M O l Manoa E L Fern E lp l Pauoa E l l Lincoln E U Puuhale E pl n Roosevelt H L Kalihi Waena E p Anuenue E & H U l pl Hahaione E Kalihi Kai E lStevenson M n Palolo E n Noelani E l Kalakaua M p p Jarrett M Niu Valley M l l Farrington H l l Hokulani E Kaiulani E l Aliiolani E l n l p n Kamiloiki E Likelike E l l Central M l n Aina Haina E Royal E l l l Kaiser H McKinley H l* p Kalani H Kaahumanu E Wilson E Koko Head E Washington M Kahala E Lunalilo E Kaimuki M Ala Wai E Kuhio E Liholiho E Kaimuki H Hawaii School for the Deaf & the Blind Jeerson E Waikiki E RS 21-0193, August 2020 (Rev. -

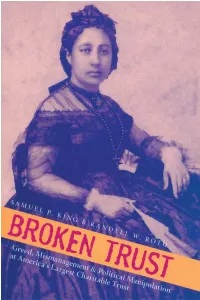

Broken Trust

Introduction to the Open Access Edition of Broken Trust Judge Samuel P. King and I wrote Broken Trust to help protect the legacy of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop. We assigned all royal- ties to local charities, donated thousands of copies to libraries and high schools, and posted source documents to BrokenTrustBook.com. Below, the Kamehameha Schools trustees explain their decision to support the open access edition, which makes it readily available to the public. That they chose to do so would have delighted Judge King immensely, as it does me. Mahalo nui loa to them and to University of Hawai‘i Press for its cooperation and assistance. Randall W. Roth, September 2017 “This year, Kamehameha Schools celebrates 130 years of educating our students as we strive to achieve the thriving lāhui envisioned by our founder, Ke Ali‘i Bernice Pauahi Bishop. We decided to participate in bringing Broken Trust to an open access platform both to recognize and honor the dedication and courage of the people involved in our lāhui during that period of time and to acknowledge this significant period in our history. We also felt it was important to make this resource openly available to students, today and in the future, so that the lessons learned might continue to make us healthier as an organization and as a com- munity. Indeed, Kamehameha Schools is stronger today in governance and structure fully knowing that our organization is accountable to the people we serve.” —The Trustees of Kamehameha Schools, September 2017 “In Hawai‘i, we tend not to speak up, even when we know that some- thing is wrong. -

KALAMA LAA, 42, of Wai'anae, Died Nov. 2, 2000. Born In

L ROBERT "BOB" KALAMA LAA, 42, of Wai‘anae, died Nov. 2, 2000. Born in Kahuku. Raised in Wai‘anae. Employed as a iron worker. Survived by wife, Patricia; daughters, Rory Lynn, Riana-Lynn and Renise; parents, Roland and Valentina Laa; brothers, Stacy and Eddie Laa; sisters, Shirley Titialii, Rita Laa, Rose Laa and Valentina Delima. Visitation 6 to 9 p.m. Wednesday at Mililani Memorial Park makai chapel, service 7 p.m. Visitation also 9 a.m. Thursday at the chapel, service 11:15 a.m.; burial 1 p.m. at Nanakuli Homestead Cemetery. Casual or aloha attire. TIMOTHY KALANI LAA SR., 40, of Wai‘anae, died Aug. 18, 2000. Born in Honolulu. Survived by wife, Nanette; sons, Timothy Jr. and Allen; daughters, Melissa and Marcy; father, Joseph Laa Sr.; brothers, Joseph Jr. and Claude; sisters, Leona Prudhomme, Eunice Simpson, Leatrice Johnson, Selene Kaipo and Lois Nichols. Visitation 6 p.m. Sunday at Mililani Memorial Park and Mortuary mauka chapel; service 7 p.m. LEONARD LEO LABANG died Jan. 5, 2000. Born in Honolulu. Survived by daughters, Darashan; son, Ramalah; father, Leon; mother, Laurita Parsons; brothers, Randy and Ted; sisters, Cynthia Anderson, Brenda Clary and Leona Komine. Visitation 10:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Thursday at Nuuanu Mortuary, service 12:30 p.m.; burial at Valley of the Temples Memorial Park. RAYSON LI PATRICK LABAYA, 22, of Honolulu, died Aug. 27, 2000. Born in Honolulu. Survived by parents, Richard and Patricia; sisters, Renee Mae Wynn, Lucy Evans, Marietta Rillera, Vanessa Lewi, Beverly, and Nadine Viray; brother, Richard Jr.; grandmothers, Sally Labaya and Beatrice Alvarico. -

FINAL PUBLIC Archaeological Preservation Plan Pahua Heiau

__________________________________________________________ Haʻa Nā ʻUala o Pahua i Ke Kula o Kamauwai The Potatoes of Pahua Danced in the Plains of Kamauwai FINAL PUBLIC Archaeological Preservation Plan Pahua Heiau Waimānalo Ahupuaʻa, Ko‘olaupoko Moku, O‘ahu Mokupuni TMK 3-9-056: 038 ____________________________________________________________ Prepared for: Prepared by: Pūlama Lima, M.A., Kelley Uyeoka, M.A., Momi Wheeler, B.A., Liʻi Bitler, B.A., Deandra Castro, B.A. Kekuewa Kikiloi, Ph.D. June 2018 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Management Summary Pahua Heiau, Waimānalo Ahupuaʻa, Koʻolaupoko Moku, Island of Oʻahu, Project Location TMK: 3-9-056: 038 Land Owner The Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) Project Area Size 1.15 acres Prepared in consultation with OHA and the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) - State Historic Preservation Division (SHPD), this preservation plan is designed to fulfill State requirements for preservation plans per Chapter 13-277 of the Hawaiʻi Administrative Rules (HAR). This Historic document was prepared to support the proposed project’s historic Preservation preservation review under Hawai‘i Revised Statutes (HRS) Chapter 6E-8 and Compliance HAR Chapter 13-275 and is intended for review and approval by the SHPD. As recommended by OHA, this preservation plan should also be viewed as a “living document” that can be revised, adapted, and changed subject to the approval of SHPD. OHA is carrying out this Preservation Plan for Pahua Heiau complex to: 1) Ensure the preservation of this cultural site. 2) Collect existing background site information. 3) Gather ethnohistorical and other community input. Justification of 4) Guide appropriate use and management of the site by OHA, its Work stewards, and visitors. -

Abraham Kaleimahoe Fernandez: a Hawaiian Saint and Royalist, 1857-1915 by Isaiah Walker

Abraham Kaleimahoe Fernandez: A Hawaiian Saint and Royalist, 1857-1915 by Isaiah Walker As the sun neared the horizon after a beautiful summer day in 1906, two Hawaiians entered the Hamohamo river in Waikiki. Elder Abraham Kaleimahoe Fernandez baptized and then confirmed Queen Lydia Kamakaeha Liliuokalani a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Although technically she was no longer the queen of Hawai’i in 1906, Elder Fernandez recorded and reported to President Samuel E. Woolley that he had baptized Her Majesty Queen Liliuokalani.1 Abraham Fernandez was both a friend and former employee of the Queen. From 1891 to 1893 he served the Kingdom of Hawaii as a member of the Queen’s Privy Council.2 According to oral family tradition, prior to becoming a member of the LDS church himself, the Queen assigned him to monitor Mormons in the islands and report on their activities and aspirations.3 Although he was first exposed to the church while spying on it, Abraham was eventually baptized a Mormon on October 22, 1895, after Peter Kealaka’ihonua, a Hawaiian elder and Fernandez family friend healed Abraham’s dying- 19-year-old-daughter, Adelaide. Shortly after his conversion, Abraham began filling important church leadership callings in the islands. He served as a full-time missionary in Hawaii, became a member of the Hawaiian mission presidency under Samuel E. Woolley, and adopted or hanai’d missionaries, prophets, and apostles who regularly visited the islands (including and most notably President Joseph F. Smith). In this presentation I will recount the history of Abraham Fernandez, his family, and his service in the church here.