Projecting MUSIC Across the Silk Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED January 13, 2015 January 7, 2015 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] ALAN GILBERT AND THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC Alan Gilbert To Conduct SILK ROAD ENSEMBLE with YO-YO MA Alongside the New York Philharmonic in Concerts Celebrating the Silk Road Ensemble’s 15TH ANNIVERSARY Program To Include The Silk Road Suite and Works by DMITRI YANOV-YANOVSKY, R. STRAUSS, AND OSVALDO GOLIJOV February 19–21, 2015 FREE INSIGHTS AT THE ATRIUM EVENT “Traversing Time and Trade: Fifteen Years of the Silkroad” February 18, 2015 The Silk Road Ensemble with Yo-Yo Ma will perform alongside the New York Philharmonic, led by Alan Gilbert, for a celebration of the innovative world-music ensemble’s 15th anniversary, Thursday, February 19, 2015, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, February 20 at 8:00 p.m.; and Saturday, February 21 at 8:00 p.m. Titled Sacred and Transcendent, the program will feature the Philharmonic and the Silk Road Ensemble performing both separately and together. The concert will feature Fanfare for Gaita, Suona, and Brass; The Silk Road Suite, a compilation of works commissioned and premiered by the Ensemble; Dmitri Yanov-Yanovsky’s Sacred Signs Suite; R. Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration; and Osvaldo Golijov’s Rose of the Winds. The program marks the Silk Road Ensemble’s Philharmonic debut. “The Silk Road Ensemble demonstrates different approaches of exploring world traditions in a way that — through collaboration, flexible thinking, and disciplined imagination — allows each to flourish and evolve within its own frame,” Yo-Yo Ma said. -

Čarobnost Zvoka in Zavesti

EDUN EDUN SLOVANSKO-PITAGOREJSKA ANSAMBEL ZA STARO MEDITATIVNO KATEDRA ZA RAZVOJ ZAVESTI GLASBO IN OŽIVLJANJE SPIRITUALNIH IN HARMONIZIRANJE Z ZVOKOM ZDRAVILNIH ZVOKOV KULTUR SVETA ČAROBNOST ZVOKA IN ZAVESTI na predavanjih, tečajih in v knjigah dr. Mire Omerzel - Mirit in koncertno-zvočnih terapijah ansambla Vedun 1 I. NAŠA RESNIČNOST JE ZVOK Snovni in nesnovni svet sestavlja frekvenčno valovanje – slišno in neslišno. Toda naša danost, tudi zvenska, je mnogo, mnogo več. Zvok je alkimija frekvenc in njihovih energij, orodje za urejanje in zdravljenje subtilnih teles duha in fizičnega telesa ter orodje za širjenje zavesti in izostrovanje čutil in nadčutil. Z zvokom (resonanco) se lahko sestavimo v harmonično celoto in uglasimo z naravnimi ritmi, zaradi razglašenosti (disonance) pa lahko zbolimo. Modrosti svetovnih glasbenih tradicij povezujejo človekovo zavest z nezavednim in nadzavednim ter z zvočnimi vzorci brezmejnega, brezčasnega in večnega. Zvok nas povezuje z Velikim Snovnim Slušnim Logosom Univerzuma in Kozmično Inteligenco življenja oziroma Zavestjo Narave, ki jo vse bolj odkrivata tudi subatomska fizika in medicina. Zvok je ključ tistih vrat »duše in srca«, ki odpirajo subtilne svetove »onkraj« običajne zavesti, v mnogodimenzionalne svetove resničnosti in zavesti ter v transcendentalne svetove. Knjige dr. Mire Omerzel - Mirit, še zlasti knjižna serija Kozmična telepatija, njene delavnice in tečaji, pa tudi koncerti in zgoščenke njenega ansambla Vedun (glasbenikov – zvočnih terapevtov – medijev, ki muzicirajo v transcendentalnem stanju zavesti), vodijo bralce in poslušalce na najgloblje ravni duše, v zvočno prvobitnost, k Viru življenja, v središče in pravljične svetove človekovega duha. Zvoku Mirit in glasbeni sodelavci z besedo, glasbo in zvočno »kirurgijo« vračajo urejajočo in zdravilno moč, nekdanjo svečeniško noto in svetost. -

Music for a New Day Artist Bio

Music for a New Day Artist bio Fariba Davody: Fariba Davody is a musician, vocalist, and teacher who first captured public eye performing classical Persian songs in Iran, and donating her proceeds from her show. She performed a lot of concerts and festivals such as the concert in Agha khan museum in 2016 in Toronto , concerts with Kiya Tabassian in Halifax and Montreal, and Tirgan festival in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2021 in Toronto. Fariba opened a Canadian branch of Avaye Mehr music and art school where she continues to teach. Raphael Weinroth-Browne: Canadian cellist and composer Raphael Weinroth- Browne has forged a uniQue career and international reputation as a result of his musical creativity and versatility. Not confined to a single genre or project, his musical activities encompass a multitude of styles and combine influences from contemporary classical, Middle Eastern, and progressive metal music. His groundbreaking duo, The Visit, has played major festivals such as Wave Gotik Treffen (Germany), 21C (Canada), and the Cello Biennale Amsterdam (Netherlands). As one half of East-meets-West ensemble Kamancello, he composed “Convergence Suite,” a double concerto which the duo performed with the Windsor Symphony Orchestra to a sold out audience. Raphael's cello is featured prominently on the latest two albums from Norwegian progressive metal band Leprous; he has played over 150 shows with them in Europe, North America, and the Middle East. Raphael has played on over 100 studio albums including the Juno Award-winning Woods 5: Grey Skies & Electric Light (Woods of Ypres) and Juno-nominated UpfRONt (Ron Davis’ SymphRONica) - both of which feature his own compositions/arrangements - as well as the Juno-nominated Ayre Live (Miriam Khalil & Against The Grain Ensemble). -

WOODWIND INSTRUMENT 2,151,337 a 3/1939 Selmer 2,501,388 a * 3/1950 Holland

United States Patent This PDF file contains a digital copy of a United States patent that relates to the Native American Flute. It is part of a collection of Native American Flute resources available at the web site http://www.Flutopedia.com/. As part of the Flutopedia effort, extensive metadata information has been encoded into this file (see File/Properties for title, author, citation, right management, etc.). You can use text search on this document, based on the OCR facility in Adobe Acrobat 9 Pro. Also, all fonts have been embedded, so this file should display identically on various systems. Based on our best efforts, we believe that providing this material from Flutopedia.com to users in the United States does not violate any legal rights. However, please do not assume that it is legal to use this material outside the United States or for any use other than for your own personal use for research and self-enrichment. Also, we cannot offer guidance as to whether any specific use of any particular material is allowed. If you have any questions about this document or issues with its distribution, please visit http://www.Flutopedia.com/, which has information on how to contact us. Contributing Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office - http://www.uspto.gov/ Digitizing Sponsor: Patent Fetcher - http://www.PatentFetcher.com/ Digitized by: Stroke of Color, Inc. Document downloaded: December 5, 2009 Updated: May 31, 2010 by Clint Goss [[email protected]] 111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007563970B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,563,970 B2 Laukat et al. -

MUS 115 a Survey of Music History

School of Arts & Science DEPT: Music MUS 115 A Survey of Music History COURSE OUTLINE The Approved Course Description is available on the web @ TBA_______________ Ω Please note: This outline will not be kept indefinitely. It is recommended students keep this outline for your records. 1. Instructor Information (a) Instructor: Dr. Mary C. J. Byrne (b) Office hours: by appointment only ( [email protected] ) – Tuesday prior to class at Camosun Lansdowne; Wednesday/Thursday at Victoria Conservatory of Music (c) Location: Fischer 346C or Victoria Conservatory of Music 320 (d) Phone: (250) 386-5311, ext 257 -- please follow forwarding instructions, 8:30 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. weekdays, 10:00 to 2:00 weekends, and at no time on holidays (e) E-mail: [email protected] (f) Website: www.vcm.bc.ca 2. Intended Learning Outcomes (If any changes are made to this part, then the Approved Course Description must also be changed and sent through the approval process.) Upon successful completion of this course, students will be able to: • Knowledgeably discuss a performance practice issue related to students’ major • Discuss select aspects of technical developments in musical instruments, including voice and orchestra. • Discuss a major musical work composed between 1830 and 1950, defending the choice as a seminal work with significant influence on later composers. • Prepare research papers and give presentations related to topics in music history. 1 MUS 115, Course Outline, Fall 2009 Mary C. J. Byrne, Ph. D. Camosun College/Victoria Conservatory of Music 3. Required -

Music, Image, and Identity: Rebetiko and Greek National Identity

Universiteit van Amsterdam Graduate School for Humanities Music, Image, and Identity: Rebetiko and Greek National Identity Alexia Kallergi Panopoulou Student number: 11655631 MA Thesis in European Studies, Identity and Integration track Name of supervisor: Dr. Krisztina Lajosi-Moore Name of second reader: Prof. dr. Joep Leerssen September 2018 2 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1 .............................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Theory and Methodology ........................................................................................................ 6 Chapter 2. ........................................................................................................................... 11 2.1 The history of Rebetiko ......................................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 Kleftiko songs: Klephts and Armatoloi ............................................................................... 11 2.1.2 The Period of the Klephts Song .......................................................................................... 15 2.2 Rebetiko Songs...................................................................................................................... 18 2.3 Rebetiko periods .................................................................................................................. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/25/2021 04:09:39AM Via Free Access 96 Yagou

Please provide footnote text CHAPTER 4 A Dialogue of Sources: Greek Bourgeois Women and Material Culture in the Long 18th Century Artemis Yagou The Context In the Ottoman-dominated Europe of the Early Modern period (17th to 19th centuries), certain non-Muslim populations, especially the Christian elites, defined their social status and identity at the intersection of East and West. The westernization of southeastern Europe proceeded not just through the spread of Enlightenment ideas and the influence of the French Revolution, but also through changes in visual culture brought about by western influence on notions of luxury and fashion. This approach allows a closer appreciation of the interactions between traditional culture, political thought, and social change in the context of the modernization or “Europeanization” of this part of Europe.1 The role of the “conquering Balkan Orthodox merchant” in these processes has been duly emphasized.2 The Balkan Orthodox merchant represented the main vehicle of interaction and interpenetration between the Ottoman realm and the West, bringing the Balkans closer to Europe than ever before.3 The gradual expansion of Greek merchants beyond local trade and their penetra- tion into export markets is the most characteristic event of the 18th century in Ottoman-dominated Greece.4 This was triggered by political developments, more specifically the treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774, the opening of the Black 1 LuxFaSS Research Project, http://luxfass.nec.ro, [accessed 30 May 2017]. 2 Troian Stoianovich. “The Conquering Balkan Orthodox Merchant,” The Journal of Economic History 20 (1960): 234–313. 3 Fatma Müge Göçek, East Encounters West: France and the Ottoman Empire in the Eighteenth Century (New York, 1987); Vladislav Lilić, “The Conquering Balkan Orthodox Merchant, by Traian Stoianovich. -

Amunowruz-Magazine-No1-Sep2018

AMU NOWRUZ E-MAGAZINE | NO. 1 | SEPTEMBER 2018 27SEP. HAPPY WORLD TOURISM DAY Taste Persia! One of the world's most ancient and important culinary schools belongs to Iran People of the world; Iran! Includes 22 historical sites and a natural one. They 're just one small portion from Iran's historical and natural resources Autumn, one name and a thousand significations About Persia • History [1] Contents AMU NOWRUZ E-MAGAZINE | NO. 1 | SEPTEMBER 2018 27SEP. HAPPY WORLD TOURISM DAY Taste Persia! One of the world's most ancient and important culinary schools belongs to Iran Editorial 06 People of the world; Iran! Includes 22 historical sites and a natural one. They 're just one small portion from Iran's historical and natural resources Autumn, one name and a thousand significations Tourism and the Digital Transformation 08 AMU NOWRUZ E-MAGAZINE NO.1 SEPTEMBER 2018 10 About Persia History 10 A History that Builds Civilization Editorial Department Farshid Karimi, Ramin Nouri, Samira Mohebali UNESCO Heritages Editor In Chief Samira Mohebali 14 People of the world; Iran! Authors Kimia Ajayebi, Katherin Azami, Elnaz Darvishi, Fereshteh Derakhshesh, Elham Fazeli, Parto Hasanizadeh, Maryam Hesaraki, Saba Karkheiran, Art & Culture Arvin Moazenzadeh, Homeira Mohebali, Bashir Momeni, Shirin Najvan 22 Tourism with Ethnic Groups in Iran Editor Shekufe Ranjbar 26 Religions in Iran 28 Farsi; a Language Rooted in History Translation Group Shekufe Ranjbar, Somayeh Shirizadeh 30 Taste Persia! Photographers Hessam Mirrahimi, Saeid Zohari, Reza Nouri, Payam Moein, -

TITLE Pages 160518

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/64500 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Young, R.C. Title: La Cetra Cornuta : the horned lyre of the Christian World Issue Date: 2018-06-13 La Cetra Cornuta : the Horned Lyre of the Christian World Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op 13 juni 2018 klokke 15.00 uur door Robert Crawford Young Born in New York (USA) in 1952 Promotores Prof. dr. h.c. Ton Koopman Universiteit Leiden Prof. Frans de Ruiter Universiteit Leiden Prof. dr. Dinko Fabris Universita Basilicata, Potenza; Conservatorio di Musica ‘San Pietro a Majella’ di Napoli Promotiecommissie Prof.dr. Henk Borgdorff Universiteit Leiden Dr. Camilla Cavicchi Centre d’études supérieures de la Renaissance Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Université de Tours Prof.dr. Victor Coelho School of Music, Boston University Dr. Paul van Heck Universiteit Leiden Prof.dr. Martin Kirnbauer Universität Basel en Schola Cantorum Basiliensis Dr. Jed Wentz Universiteit Leiden Disclaimer: The author has made every effort to trace the copyright and owners of the illustrations reproduced in this dissertation. Please contact the author if anyone has rights which have not been acknowledged. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Foreword ix Glossary xi Introduction xix (DE INVENTIONE / Heritage, Idea and Form) 1 1. Inventing a Christian Cithara 2 1.1 Defining -

Kayhan Kalhor/Erdal Erzincan the Wind

ECM Kayhan Kalhor/Erdal Erzincan The Wind Kayhan Kalhor: kamancheh; Erdal Erzincan: baglama; Ulaş Özdemir: divan baglama ECM 1981 CD 6024 985 6354 (0) Release: September 26, 2006 After “The Rain”, his Grammy-nominated album with the group Ghazal, comes “The Wind”, a documentation of Kayhan Kalhor’s first encounter with Erdal Erzincan. It presents gripping music, airborne music indeed, pervasive, penetrating, propelled into new spaces by the relentless, searching energies of its protagonists. Yet it is also music firmly anchored in the folk and classical traditions of Persia and Turkey. Iranian kamancheh virtuoso Kalhor does not undertake his transcultural projects lightly. Ghazal, the Persian-Indian ‘synthesis’ group which he initiated with sitarist Shujaat Husain Khan followed some fifteen years of dialogue with North Indian musicians, in search of the right partner. “Because I come from a musical background which is widely based on improvisation, I really like to explore this element with players from different yet related traditions, to see what we can discover together. I’m testing the water – putting one foot to the left, so to speak, in Turkey. And one foot to the right, in India. I’m between them. Geographically, physically, musically. And I’m trying to understand our differences. What is the difference between Shujaat and Erdal? Which is the bigger gap? And where will this lead?” Kayhan began his association with Turkish baglama master Erdal Erzincan by making several research trips, in consecutive years, to Istanbul, collecting material, looking for pieces that he and Erdal might play together. He was accompanied on his journeys by musicologist/player Ulaş Özdemir who also served as translator and eventually took a supporting role in the Kalhor/Erzincan collaboration. -

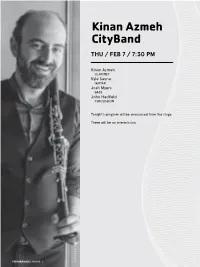

Kinan Azmeh Cityband THU / FEB 7 / 7:30 PM

Kinan Azmeh CityBand THU / FEB 7 / 7:30 PM Kinan Azmeh CLARINET Kyle Sanna GUITAR Josh Myers BASS John Hadfield PERCUSSION Tonight’s program will be announced from the stage. There will be no intermission. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 6 Tsang Connie by Photo ABOUT THE ARTIST KINAN AZMEH (CLARINET) Hailed as a “virtuoso” and “intensely soulful” by The New York Times and “spellbinding” by The New Yorker, Kinan’s utterly distinctive sound, crossing different musical genres, has gained him international recognition as a clarinetist and composer. Kinan was recently composer-in-residence with Classical Movements for the 2017/18 season. Kinan has toured the world as a soloist, composer and improviser. Notable appearances include Opera Bastille, Paris; Tchaikovsky Grand Hall, Moscow; Carnegie Hall and the UN's general assembly, New York; the Royal Albert Hall, London; Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires; der Philharmonie, Berlin; the Library of Congress and The Kennedy Center, Washington, D.C.; the Mozarteum, Salzburg, Austria; Elbphilharmonie, Hamburg; and the Damascus Opera His discography includes three albums Kinan is a graduate of New York's House for its opening concert in his with his ensemble, Hewar, several Juilliard School as a student of native Syria. soundtracks for film and dance, a duo Charles Neidich, both of the album with pianist Dinuk Wijeratne and Damascus High Institutes of Music He has appeared as soloist with the an album with his New York Arabic/Jazz where he studied with Shukry Sahwki, New York Philharmonic, the Seattle quartet, the Kinan Azmeh CityBand. Nicolay Viovanof and Anatoly Moratof, Symphony, the Bavarian Radio He serves as artistic director of the and of Damascus University’s School Orchestra, the West-Eastern Divan Damascus Festival Chamber Players, of Electrical Engineering in his native Orchestra, the Qatar Philharmonic and a pan-Arab ensemble dedicated to Syria. -

The Rose Art Museum Presents Syrian-Armenian Artist Kevork

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Nina J. Berger, [email protected] 617.543.1595 THE ROSE ART MUSEUM PRESENTS SYRIAN-ARMENIAN ARTIST KEVORK MOURAD’S IMMORTAL CITY “Culture Cannot Wait” program brings experts in preserving cultural heritage to Brandeis campus (Waltham, Mass.) – The Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University presents Immortal City, an exhibition of new paintings by acclaimed Syrian-Armenian artist Kevork Mourad created in response to the war in Syria and the destruction of the artist’s beloved city of Aleppo, September 8, 2017 – January 21, 2018. A public opening reception to celebrate the museum’s fall exhibition season will be held 6–9 pm on Saturday, October 14. Kevork Mourad (b. Syria 1970) is known for paintings made spontaneously in collaboration with composers, dancers, and musicians. Of Armenian descent, Mourad performs in his art both a vital act of remembering and a poetic gesture of creativity in the face of tragedy, as he mediates the experience of trauma through finely wrought, abstracted imagery that celebrates his rich cultural heritage even as he mourns its loss. Mourad’s paintings ask viewers to stop and bear witness, to see the fragments of a culture destroyed – textiles, ancient walls, Arabic calligraphy, and bodies crushed by war. Using a unique method that incorporates monoprinting and his own technique of applying paint with one finger in a sweeping gesture, Mourad produces paintings that are fantastical, theatrical, and lyrical, the line reflecting the music that is such an integral part of his practice. An 18th-century etching from the Rose’s permanent collection by Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranisi will accompany Mourad’s work and locate Mourad's practice within a centuries-old artistic interest and fascination with the city in ruins.