A SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPROACH to TV EDITING by Ellen Thomas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Producer's Handbook

DEVELOPMENT AND OTHER CHALLENGES A PRODUCER’S HANDBOOK by Kathy Avrich-Johnson Edited by Daphne Park Rehdner Summer 2002 Introduction and Disclaimer This handbook addresses business issues and considerations related to certain aspects of the production process, namely development and the acquisition of rights, producer relationships and low budget production. There is no neat title that encompasses these topics but what ties them together is that they are all areas that present particular challenges to emerging producers. In the course of researching this book, the issues that came up repeatedly are those that arise at the earlier stages of the production process or at the earlier stages of the producer’s career. If not properly addressed these will be certain to bite you in the end. There is more discussion of various considerations than in Canadian Production Finance: A Producer’s Handbook due to the nature of the topics. I have sought not to replicate any of the material covered in that book. What I have sought to provide is practical guidance through some tricky territory. There are often as many different agreements and approaches to many of the topics discussed as there are producers and no two productions are the same. The content of this handbook is designed for informational purposes only. It is by no means a comprehensive statement of available options, information, resources or alternatives related to Canadian development and production. The content does not purport to provide legal or accounting advice and must not be construed as doing so. The information contained in this handbook is not intended to substitute for informed, specific professional advice. -

Freeze Frame by Lydia Rypcinski 8 Victoria Tahmizian Bowling and Other [email protected] Fun at 45 Below Zero

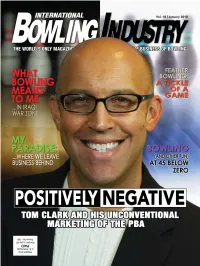

THE WORLD'S ONLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED EXCLUSIVELY TO THE BUSINESS OF BOWLING CONTENTS VOL 18.1 PUBLISHER & EDITOR Scott Frager [email protected] Skype: scottfrager 6 20 MANAGING EDITOR THE ISSUE AT HAND COVER STORY Fred Groh More than business Positively negative [email protected] Take a close look. You want out-of-the-box OFFICE MANAGER This is a brand new IBI. marketing? You want Tom Patty Heath By Scott Frager Clark. How his tactics at [email protected] PBA are changing the CONTRIBUTORS way the media, the public 8 Gregory Keer and the players look Lydia Rypcinski COMPASS POINTS at bowling. ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Freeze frame By Lydia Rypcinski 8 Victoria Tahmizian Bowling and other [email protected] fun at 45 below zero. By Gregory Keer 28 ART DIRECTION & PRODUCTION THE LIGHTER SIDE Designworks www.dzynwrx.com A feather in your 13 (818) 735-9424 cap–er, lane PORTFOLIO Feather bowling’s the FOUNDER Allen Crown (1933-2002) What was your first game where the balls job, Cathy DeSocio? aren’t really balls, there are no bowling shoes, 13245 Riverside Dr., Suite 501 Sherman Oaks, CA 91423 and the lanes aren’t even 13 (818) 789-2695(BOWL) flat. But people come What was your first Fax (818) 789-2812 from miles around, pay $40 job, John LaSpina? [email protected] an hour, and book weeks in advance. www.BowlingIndustry.com 14 HOTLINE: 888-424-2695 What Bowling 32 Means to Me THE GRAPEVINE SUBSCRIPTION RATES: One copy of Two bowling International Bowling Industry is sent free to A tattoo league? every bowling center, independently owned buddies who built a lane 20 Go ahead and laugh but pro shop and collegiate bowling center in of their own when their the U.S., and every military bowling center it’s a nice chunk of and pro shop worldwide. -

MARGARET KAMINSKI 2354 Ewing Street, Los Angeles, CA 90039 646.207.8652 • [email protected]

MARGARET KAMINSKI 2354 Ewing Street, Los Angeles, CA 90039 646.207.8652 • [email protected] EXPERIENCE Nickelodeon, Los Angeles, CA 2016 – Present Writer, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe Awards (2019) Writer, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe Sports Awards (2018) Writer, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe Awards (2018) Writers’ Assistant, Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards (2017) Writers’ Assistant, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe SPorts Awards (2017) Writers’ Assistant, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe SPorts Awards (2016) Above Average Productions, Los Angeles, CA January 2018 – Present Freelance Writer Live From WZRD, Warner Media/VRV, Los Angeles, CA November 2018 – MarCh 2019 Staff Writer Scholastic’s Choices Magazine, New York, New York Video Producer, Story Editor MarCh 2018 – Present Freelance Writer February 2015 – Present Assistant Editor, Managing Editor of Teaching Resources May 2012 – February 2015 SKOOGLE Pilot (All That Reboot), PoCket.WatCh, Los Angeles, CA April 2018 – August 2018 Contributing Writer (punch-up) E! Live from the Red Carpet, Los Angeles, CA August 2017 – November 2018 August 2017 – Present Writer The 2018 PeoPle’s ChoiCe Awards The 2018 Primetime Emmy Awards The 2017 Primetime Emmy Awards The 2017 AmeriCan MusiC Awards The 2018 Golden Globes The 2018 SCreen ACtors Guild Awards The 2018 Grammy Awards MTV Movie + TV Awards Pre-Show, Los Angeles, CA May 2018 – June 2018 Writer PotterCon/Wizard U., National/Touring July 2012 – January 2018 Executive Producer Fallen For You: Pilot, Los Angeles, CA DeCember 2016 Writers’ Assistant Collier.Simon, Los Angeles, CA February 2016 – Present Freelance Writer Masthead Media, New York, NY SePtember 2015 – February 2016 Freelance Writer PMK•BNC (Vowel), New York, NY MarCh 2015 – SePtember 2015 Freelance Writer EDUCATION Barnard College, Columbia University, B.A. -

Rec Center Gets a Makeover Dordt Instructor Challenges Steve King for Congress Concert Choir Tour: Ain't No Sickness Can Hold

Dordt NISO Dordt Changes media concert theatre to DCC truck Piano in ACTF Dreamer page 3 page 3 page 4 page 8 January 31, 2019 Issue 1 Follow us online Concert Choir tour: ain’t no sickness can hold them down Haemi Kim -- Staff Writer could incorporate this beautiful language into our piece. I loved the excitement on people’s During winter break, Dordt College Concert faces in the audience—or fear among the high Choir and its conductor Ryan Smit went on a schoolers—when we did this song and I had tour, sharing their talents to many different people at almost every stop come up to me audiences. It was a week-long tour going afterwards and thank me for it.” around Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana. Even though the choir tour was a blast to Many of the choir students enjoyed being on many of the choir members, this year, the tour because it was an opportunity to meet other stomach flu spread within the choir, affecting choir members and build relationships with around 14 students, and even the conductor other choir members. during their last concert before coming back. “It’s a unique opportunity to get to know the Because of this, TeBrake and Seaman stepped other choir members outside of the choir room,” up to conduct the last concert, each taking half said senior soprano Kourtney TeBrake. of the performance. “Before tour, you recognize people in the As music education majors, it wasn’t their first choir, maybe know their names, but when you time conducting for a choir. -

THE WRITE CHOICE by Spencer Rupert a Thesis Presented to The

THE WRITE CHOICE By Spencer Rupert A thesis presented to the Independent Studies Program of the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirements for the degree Bachelor of Independent Studies (BIS) Waterloo, Canada 2009 1 Table of Contents 1 Abstract...................................................................................................................................................7 2 Summary.................................................................................................................................................8 3 Introduction.............................................................................................................................................9 4 Writing the Story...................................................................................................................................11 4.1 Movies...........................................................................................................................................11 4.1.1 Writing...................................................................................................................................11 4.1.1.1 In the Beginning.............................................................................................................11 4.1.1.2 Structuring the Story......................................................................................................12 4.1.1.3 The Board.......................................................................................................................15 -

Canadian Canada $7 Spring 2020 Vol.22, No.2 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SPRING 2020 VOL.22, NO.2 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA The Law & Order Issue The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style Peter Mitchell on Murdoch’s 200th ep Floyd Kane Delves into class, race & gender in legal PM40011669 drama Diggstown Help Producers Find and Hire You Update your Member Directory profile. It’s easy. Login at www.wgc.ca to get started. Questions? Contact Terry Mark ([email protected]) Member Directory Ad.indd 1 3/6/19 11:25 AM CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 22 No. 2 Spring 2020 Contents ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Cover Publisher Maureen Parker Diggstown Raises Kane To New Heights 6 Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Creator and showrunner Floyd Kane tackles the intersection of class, race, gender and the Canadian legal system as the Director of Communications groundbreaking CBC drama heads into its second season Lana Castleman By Li Robbins Editorial Advisory Board Michael Amo Michael MacLennan Features Susin Nielsen The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style 12 Simon Racioppa Rachel Langer With a solid background investigating and writing about true President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) crime, showrunner Petro Duszara and his team tell us why this Councillors series is resonating with viewers and lawmakers alike. Michael Amo (Atlantic) By Matthew Hays Marsha Greene (Central) Alex Levine (Central) Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) Murdoch Mysteries’ Major Milestone 16 Lienne Sawatsky (Central) Andrew Wreggitt (Western) Showrunner Peter Mitchell reflects on the successful marriage Design Studio Ours of writing and crew that has made Murdoch Mysteries an international hit, fuelling 200+ eps. -

Download Original 12.98 MB

FRONT COVER SPRING | IN THE WRITERS’ ROOM | THE HEART OF PARIS | DAWN CHORUS DIMINUENDO cover_final.indd 1 4/23/20 2:50 PM Cover illustration by Anuj Shrestha Finches such as this siskin are among the bird families whose numbers have declined precipitously in the last years. Read more in “Dawn Chorus Diminuendo” on page . LILLIAN KING/GETTY IMAGES ifc-pg1_toc_final.indd 2 4/23/20 2:57 PM magazine.wellesley.edu Spring 2020 @Wellesleymag FEATURES DEPARTMENTS In the Writers’ Room From the Editor WCAA By Lisa Scanlon Mogolov ’ Letters to the Editor Class Notes The Heart of Paris From the President In Memoriam By Paula Butturini ’ Window on Wellesley Endnote Dawn Chorus Diminuendo By Catherine O’Neill Grace Shelf Life This magazine is published by the Wellesley College Alumnae Association, which has a mission “to support the institutional priorities of Wellesley College by connecting alumnae to the College and to each other.” ifc-pg1_toc_final.indd 3 4/23/20 2:57 PM From the Editor VOLUME , ISSUE NO. am certain that when the class of ’20 returns for its 50th reunion in 2070, the memory of their fi nal week on campus will be as vivid to them then as it is today. I write this on March Editor Alice M. Hummer 16. The last fi ve days on campus have been simultaneously completely heartwrenching and utterly heartwarming. Senior Associate Editors Lisa Scanlon Mogolov ’99 The College announced its decision to suspend classes and go to remote teaching last Catherine O’Neill Grace IThursday. Somehow, the seniors managed to paint the campus red overnight—festooning Design departments in the traditional decorations in their class color—and wore their robes for “the Hecht/Horton Partners, Arlington, Mass. -

AGREEMENT (“Agreement”)

INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT (“Agreement”) covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS TELEVISION PROGRAMS and OTHER PRODUCTION between The WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA (the “Guild” or the “WGC”) and The CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION (the “Association” or the “CMPA”) July 1, 2019 to June 30, 2022 © 2019 WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA and CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCERS ASSOCIATION. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A: General – All Productions p. 1 Article A1 Recognition, Application and Term p. 1 Article A2 Definitions p. 4 Article A3 General Provisions p. 14 Article A4 No Strike and Unfair Declaration p. 15 Article A5 Grievance Procedures and Resolution p. 16 Article A6 Speculative Writing, Sample Pages and Unsolicited Scripts p. 21 Article A7 Copyright and Contracts; Warranties, Indemnities and Rights p. 23 Article A8 Story Editors and Story Consultants p. 28 Article A9 Credits p. 29 Article A10 Security for Payment p. 41 Article A11 Payments p. 43 Article A12 Administration Fee p. 50 Article A13 Insurance and Retirement Plan, Deductions from Writer’s Fees p. 51 Article A14 Contributions and Deductions from Writer’s Fees in the case of Waivers p. 52 Section B: Conditions Governing Engagement p. 54 Article B1 Conditions Governing Engagement for all Program Types p. 54 Article B2 Optional Bibles, Script/Program Development p. 60 Article B3 Options p. 61 Section C: Additional Conditions and Minimum Compensation by Program Type p. 63 Article C1 Feature Film p. 63 Article C2 Optional Incentive Plan for Feature Films p. 66 Article C3 Television Production (Television Movies) p. 71 Article C4 Television Production (Other than Television Movies) p. -

ANN Macnaughton

WIFVV INTERVIEW WIFVVANN INTERVIEW MacNAUGHTON WIFVV INTERVIEW WIFVV Ann MacNaughton shared her extensive experience as a MD: In all of that are actors’ schedules, up to speed with the characters and what beats writer and story editor with a Vancouver audience at the contractual obligations…. have to be hit to build the rest of the season. If you recent Trade Forum. Her credits include story editor on AM: Absolutely. The stars always get the A plots; have to bring in writers, you try to select episodes E.N.G., My Life as a Dog, and Danger Bay; writer on but who gets more A plots, or do you balance them that don’t have many series arcs in them, or you episodic TV including Riverdale, Street Legal, and all equally? There is a rhythm to the season just as simply ask for well-crafted stories set in the series Road to Avonlea; and co-producer on Traders. Writer much as to an episode. And you may have fifteen arena and add the arcs yourself. Michelle Demers hooked up with Ann after the Forum 7-day shoots, but have to build in seven 6-day Other series, like Wind at My Back, where the for an informative look into the world of story shoots; you may have one actor guaranteed four stories are more stand-alone—a set of characters are departments. days per episode, another only two days. You may defined but it’s not about their progress through be allowed no more than fifty extras per episode, the season, and the world is distinctive but not Michelle Demers: Tell us about the road here. -

Technical/Design?

Career & Employment Services (CES) www.uleth.ca/ross/ces What can I do with a Major in Technical/Design? The Technical/Design Program at the University of Lethbridge The Bachelor of Fine Arts (Dramatic Arts) is a four- year degree that provides vibrant and varied practical opportunities for students to immerse themselves in the world of theatre and drama. Students complete a core program of courses in theatre theory and history, performance, and technical theatre/design. Technical Design students are introduced to all areas For more information on the of production and design including scenery, Technical/Design Major at the U of L: properties, costumes, makeup, lighting, sound and http://www.uleth.ca/finearts/drama stage management through a combination of academic and production assignments. Students develop practical hands-on skills in a minimum of Faculty of Fine Arts two technical areas through production assignments. W660 University Centre for the Arts Qualifying senior-level students may have the Phone: 403-380-1864 opportunity for major technical or design Email: See Contact Website assignments on the Department Mainstage Academic Advising: productions. http://www.uleth.ca/finearts/departments/dram a/student-advising Students may also consider pursuing a combined Bachelor of Fine Arts (Dramatic Arts)/Bachelor of Education (Drama Education). Skills Developed • Active Listening & • Critical & Creative • Presentation Questioning Thinking • Problem-Solving • Adaptability • Demonstrate Creativity & • Reporting & Editing • Appreciation -

PRODUCTION TEAM Dan Habib, Producer

INTELLIGENT LIVES- PRODUCTION TEAM Dan Habib, Producer/Director/Cinematographer Dan Habib is the creator of the award-winning documentary films Including Samuel, Who Cares About Kelsey?, Mr. Connolly Has ALS (an IDA nominee for Best Short), INTELLIGENT LIVES and many other films on disability issues. Habib's films have been featured in dozens of film festivals, broadcast internationally, nominated for Emmy awards and translated into 17 languages for worldwide distribution. Habib is a filmmaker at the University of New Hampshire’s Institute on Disability and gave a widely viewed TEDx talk, “Disabling Segregation.” He received the Champion of Human and Civil Rights Award from the National Education Association, and the Justice for All Grassroots Award from the American Association of People with Disabilities. In 2014, Habib was appointed by President Barack Obama to the President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities. Habib and his wife, Betsy, live in Concord, NH, with their sons Isaiah, 21, and Samuel, 18. Samuel has cerebral palsy and was the subject of Habib’s first film Including Samuel. Chris Cooper, Narrator/Executive Producer Chris Cooper won the 2003 Best Supporting Actor Academy Award for his role in Adaptation. He has been an actor on stage, screen, and television for three decades, with notable roles in Lone Star, American Beauty, Seabiscuit, The Bourne Identity, October Sky, August Osage County, Lonesome Dove, and dozens of other films. In 1987, Cooper and his wife Marianne Leone had their son Jesse, who had cerebral palsy and epilepsy. They became advocates for inclusive education, and Jesse became a high school honor student. -

WRITING for EPISODIC TV from Freelance to Showrunner

WRITING FOR EPISODIC TV From Freelance to Showrunner Written by: Al Jean Brad Kern Jeff Melvoin Pamela Pettler Dawn Prestwich Pam Veasey John Wirth Nicole Yorkin Additional Contributions by: Henry Bromell, Mitch Burgess, Carlton Cuse, Robin Green, Barbara Hall, Al Jean, Amy Lippman, Dan O’Shannon, Phil Rosenthal, Joel Surnow, John Wells, Lydia Woodward Edited by: John Wirth Jeff Melvoin i Introduction: Writing for Episodic Television – A User’s Guide In the not so distant past, episodic television writers worked their way up through the ranks, slowly in most cases, learning the ropes from their more-experienced colleagues. Those days are gone, and while their passing has ushered in a new age of unprecedented mobility and power for television writers, the transition has also spelled the end of both a traditional means of education and a certain culture in which that education was transmitted. The purpose of this booklet is twofold: first, to convey some of the culture of working on staff by providing informal job descrip- tions, a sense of general expectations, and practical working tips; second, to render relevant WGA rules into reader-friendly lan- guage for staff writers and executive producers. The material is organized into four chapters by job level: FREE- LANCER, STAFF WRITER/STORY EDITOR, WRITER-PRODUCER, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER. For our purposes, executive producer and showrunner are used interchangeably, although this is not always the case. Various appendices follow, including pertinent sections of the WGA Minimum Basic Agreement (MBA). As this is a booklet, not a book, it does not make many distinc- tions among the different genres found in episodic television (half- hour, animation, primetime, cable, first-run syndication, and so forth).