The WGC Showrunner Code Found Its Origin in the Largest Gathering Ever of Canada’S Top Showrunners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This List Is Meant for Reference Only – All Credits Below Should Be

LIST OF ACCEPTABLE CREDITS --- TELEVISION & DIGITAL MEDIA CATEGORIES This list is meant for reference only – all credits below should be considered eligible, unless otherwise specified in the 2018 Canadian Screen Awards TV and Digital Media Rules & Regulations booklet Appeals will be considered by the Awards Director for any credits not listed here. The production company may submit a letter stating why they feel the entrant should be included, as well as an explanation of their role in the production; this letter should be addressed to Louis Calabro, Director, Awards & Special Events. Please Note: Not all categories are listed in this document. Program Categories (not including DDDigitalDigital MMMedia,Media, NNNewsNews and SSSports)Sports) Executive Producer Executive Producer For (broadcaster) Co-Executive Producer Producer or Produced by Supervising Producer Series Producer Senior Producer (for informational / doc / talk shows / sports / “analytical” programming) Commissioning Editor (for informational / doc / talk shows / sports / “analytical” programming) Senior Executive Producer (for in house documentaries and broadcaster produced shows only) Episode Producer Content Producer For Best Factual Program or Series (1026) – Director or Producer eligible Note: For all Doc PROGRAM categories (Not Series) – “Director” is eligible Digital Media, News, Sports and Research Categories Any credit may enter, unless otherwise stated in Rules & Regulations booklet Directing (2001 ––– 2013) Only 2 entrants for this category. Any additional names -

How to Find Your Readers As a Fiction Writer

How to find Your readers as a fiction writer a 4-step workbook to walk4 you through finding your readership online Many fiction writers believe that they don’t need a platform. And while it’s true that literary agents and editors don’t expect aspiring novelists to have platforms, it’s just as true that writers must know how to find their readers if they want long-term success. Unfortunately, a lack of familiarity with the online landscape and a discomfort with putting creative work out there can cripple even the most promising book launch. This workbook will show you how to start putting your work in front of potential readers now, so that you can earn the trust and goodwill of the readership your work deserves. Building an author platform will allow you to: Sell more copies of existing books with less effort Launch a new book (or other content) successfully Get to know your readers so you can serve them better Avoid burnout so that book marketing is sustainable and rewarding Make a living as a full-time writer step 1: you Writing anything--whether it’s a novel or a tweet--starts with you. A platform will be meaningless drudgery if it doesn’t revolve around topics you love to talk about and read about. So here’s a chance to visualize yourself just as clearly as you would your next main character. This charac- ter sketch will help you pull up all the words that define you and lay them out visually, so you can inspect them as a whole. -

A Producer's Handbook

DEVELOPMENT AND OTHER CHALLENGES A PRODUCER’S HANDBOOK by Kathy Avrich-Johnson Edited by Daphne Park Rehdner Summer 2002 Introduction and Disclaimer This handbook addresses business issues and considerations related to certain aspects of the production process, namely development and the acquisition of rights, producer relationships and low budget production. There is no neat title that encompasses these topics but what ties them together is that they are all areas that present particular challenges to emerging producers. In the course of researching this book, the issues that came up repeatedly are those that arise at the earlier stages of the production process or at the earlier stages of the producer’s career. If not properly addressed these will be certain to bite you in the end. There is more discussion of various considerations than in Canadian Production Finance: A Producer’s Handbook due to the nature of the topics. I have sought not to replicate any of the material covered in that book. What I have sought to provide is practical guidance through some tricky territory. There are often as many different agreements and approaches to many of the topics discussed as there are producers and no two productions are the same. The content of this handbook is designed for informational purposes only. It is by no means a comprehensive statement of available options, information, resources or alternatives related to Canadian development and production. The content does not purport to provide legal or accounting advice and must not be construed as doing so. The information contained in this handbook is not intended to substitute for informed, specific professional advice. -

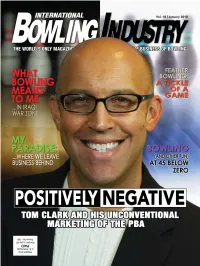

Freeze Frame by Lydia Rypcinski 8 Victoria Tahmizian Bowling and Other [email protected] Fun at 45 Below Zero

THE WORLD'S ONLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED EXCLUSIVELY TO THE BUSINESS OF BOWLING CONTENTS VOL 18.1 PUBLISHER & EDITOR Scott Frager [email protected] Skype: scottfrager 6 20 MANAGING EDITOR THE ISSUE AT HAND COVER STORY Fred Groh More than business Positively negative [email protected] Take a close look. You want out-of-the-box OFFICE MANAGER This is a brand new IBI. marketing? You want Tom Patty Heath By Scott Frager Clark. How his tactics at [email protected] PBA are changing the CONTRIBUTORS way the media, the public 8 Gregory Keer and the players look Lydia Rypcinski COMPASS POINTS at bowling. ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Freeze frame By Lydia Rypcinski 8 Victoria Tahmizian Bowling and other [email protected] fun at 45 below zero. By Gregory Keer 28 ART DIRECTION & PRODUCTION THE LIGHTER SIDE Designworks www.dzynwrx.com A feather in your 13 (818) 735-9424 cap–er, lane PORTFOLIO Feather bowling’s the FOUNDER Allen Crown (1933-2002) What was your first game where the balls job, Cathy DeSocio? aren’t really balls, there are no bowling shoes, 13245 Riverside Dr., Suite 501 Sherman Oaks, CA 91423 and the lanes aren’t even 13 (818) 789-2695(BOWL) flat. But people come What was your first Fax (818) 789-2812 from miles around, pay $40 job, John LaSpina? [email protected] an hour, and book weeks in advance. www.BowlingIndustry.com 14 HOTLINE: 888-424-2695 What Bowling 32 Means to Me THE GRAPEVINE SUBSCRIPTION RATES: One copy of Two bowling International Bowling Industry is sent free to A tattoo league? every bowling center, independently owned buddies who built a lane 20 Go ahead and laugh but pro shop and collegiate bowling center in of their own when their the U.S., and every military bowling center it’s a nice chunk of and pro shop worldwide. -

STEPHEN MOYER in for ITV, UK

Issue #7 April 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming LIVING WITH SECRETS STEPHEN MOYER IN for ITV, UK MIPTV Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com Scripted OFC Apr17.indd 2 13/03/2017 16:39 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. Brand new second season. based on the acclaimed dilemmas, this five-part series Winner – TVFI Prix Export Fiction Award 2017. author Åsa Larsson’s tells the amazing true story of CANAL+ CREATION ORIGINALE best-selling crime novels. a notorious criminal barrister. Sinister events engulf a group of friends Ellen follows a difficult teenage girl trying A husband searches for the truth when A country pub singer has a chance meeting when they visit the abandoned Black to take control of her life in a world that his wife is the victim of a head-on with a wealthy city hotelier which triggers Lake ski resort, the scene of a horrific would rather ignore her. Winner – Best car collision. Was it an accident or a series of events that will change her life crime. Single Drama Broadcast Awards 2017. something far more sinister? forever. New second series in production. MIPTV Stand C20.A banijayrights.com Banijay_TBI_DRAMA_DPS_AW.inddScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay Apr17.indd 2 1 15/03/2017 12:57 15/03/2017 12:07 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. -

{FREE} Showrunners : How to Run a Hit TV Show Ebook, Epub

SHOWRUNNERS : HOW TO RUN A HIT TV SHOW PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tara Bennett | 240 pages | 02 Sep 2014 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781783293575 | English | London, United Kingdom Showrunners : How to Run a Hit TV Show PDF Book Good insight, but essentially just a transcript of the documentary of the same name. Open Preview See a Problem? The doorbell dings. TV ratings are a real measure of a showrunner's success. The film intends to show audiences the huge amount of work that goes into making sure their favorite TV series airs on time as well as the many challenges that showrunners have to overcome to make sure a new series makes it onto the schedules at all! In the past few years, the recognition of the showrunner has grown exponentially. Other Septembers, Many Americas. Find books coming soon in But taking the culmination of a half-dozen answers of a few lines each to a question, still gives Showrunners by Tara Bennett is a companion books to the documentary "Showrunners: The Art of Running a TV Show. If you are at all interested in becoming a writer for TV or for film, this book is for you. It's a great read and adaptation of of the documentary. Blood Brothers. Plus you can tell they both really CARE. Very interesting insight of showrunning and the tv show industry. I Told You So. Find lots more television-related content on the next page. I'm excited to watch the doc that goes along with it. These people are responsible for creating, writing and overseeing every element of production on one of the United State's biggest exports - television drama and comedy series. -

MARGARET KAMINSKI 2354 Ewing Street, Los Angeles, CA 90039 646.207.8652 • [email protected]

MARGARET KAMINSKI 2354 Ewing Street, Los Angeles, CA 90039 646.207.8652 • [email protected] EXPERIENCE Nickelodeon, Los Angeles, CA 2016 – Present Writer, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe Awards (2019) Writer, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe Sports Awards (2018) Writer, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe Awards (2018) Writers’ Assistant, Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards (2017) Writers’ Assistant, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe SPorts Awards (2017) Writers’ Assistant, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe SPorts Awards (2016) Above Average Productions, Los Angeles, CA January 2018 – Present Freelance Writer Live From WZRD, Warner Media/VRV, Los Angeles, CA November 2018 – MarCh 2019 Staff Writer Scholastic’s Choices Magazine, New York, New York Video Producer, Story Editor MarCh 2018 – Present Freelance Writer February 2015 – Present Assistant Editor, Managing Editor of Teaching Resources May 2012 – February 2015 SKOOGLE Pilot (All That Reboot), PoCket.WatCh, Los Angeles, CA April 2018 – August 2018 Contributing Writer (punch-up) E! Live from the Red Carpet, Los Angeles, CA August 2017 – November 2018 August 2017 – Present Writer The 2018 PeoPle’s ChoiCe Awards The 2018 Primetime Emmy Awards The 2017 Primetime Emmy Awards The 2017 AmeriCan MusiC Awards The 2018 Golden Globes The 2018 SCreen ACtors Guild Awards The 2018 Grammy Awards MTV Movie + TV Awards Pre-Show, Los Angeles, CA May 2018 – June 2018 Writer PotterCon/Wizard U., National/Touring July 2012 – January 2018 Executive Producer Fallen For You: Pilot, Los Angeles, CA DeCember 2016 Writers’ Assistant Collier.Simon, Los Angeles, CA February 2016 – Present Freelance Writer Masthead Media, New York, NY SePtember 2015 – February 2016 Freelance Writer PMK•BNC (Vowel), New York, NY MarCh 2015 – SePtember 2015 Freelance Writer EDUCATION Barnard College, Columbia University, B.A. -

Rec Center Gets a Makeover Dordt Instructor Challenges Steve King for Congress Concert Choir Tour: Ain't No Sickness Can Hold

Dordt NISO Dordt Changes media concert theatre to DCC truck Piano in ACTF Dreamer page 3 page 3 page 4 page 8 January 31, 2019 Issue 1 Follow us online Concert Choir tour: ain’t no sickness can hold them down Haemi Kim -- Staff Writer could incorporate this beautiful language into our piece. I loved the excitement on people’s During winter break, Dordt College Concert faces in the audience—or fear among the high Choir and its conductor Ryan Smit went on a schoolers—when we did this song and I had tour, sharing their talents to many different people at almost every stop come up to me audiences. It was a week-long tour going afterwards and thank me for it.” around Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana. Even though the choir tour was a blast to Many of the choir students enjoyed being on many of the choir members, this year, the tour because it was an opportunity to meet other stomach flu spread within the choir, affecting choir members and build relationships with around 14 students, and even the conductor other choir members. during their last concert before coming back. “It’s a unique opportunity to get to know the Because of this, TeBrake and Seaman stepped other choir members outside of the choir room,” up to conduct the last concert, each taking half said senior soprano Kourtney TeBrake. of the performance. “Before tour, you recognize people in the As music education majors, it wasn’t their first choir, maybe know their names, but when you time conducting for a choir. -

Program Overview Screenwriting Research Network

Program Overview Screenwriting Research Network 7. International Conference 17—19 October 2014 Screenwriting and Directing Audiovisual Media Keynotes by Milcho Manchevski, Jutta Brückner & Brian Winston Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, Potsdam, Germany FILMUNIVERSITÄT BABELSBERG KONRAD WOLF Conference website: www.filmuniversitaet.de/de/forschung/tagungen-symposien/tagungen/tma/detail/6706.html Thursday, 16 October 3 —5 pm Sightseeing: Potsdam Park Sanssouci www.potsdam-park-sanssouci.de/sitemap-eng.html We organized a guided tour of Sanssouci (castle and park) Thursday afternoon, October 16th, 3-5 pm. The tour is in English language with access for a group of max. 40 entrants. The fee must be shared: depending on the number of participants it could be 9,50 Euro each (40p.) up to 19 Euro (20p.) Please sign in: http://doodle.com/qyyrf69hu7yis9m8 6—9 pm Opening Reception & Get Together @ Wissenschaftsetage Potsdam (rsvp) Bildungsforum Potsdam, Am Kanal 47, 14467 Potsdam (4th floor) > www.wis-potsdam.de/en Friday, 17 October 9 am Registration (entrance hall, first floor) 10 am Welcome by PROFESSOR DR. SUSANNE STÜRMER, PRESIDENT OF FILM UNIVERSITY BABELSBERG KONRAD WOLF, PROFESSOR DR. KERSTIN STUTTERHEIM, CONFERENCE HOST AND KIRSI RINNE, CHAIR SRN 10:30 am Keynote by MILCHO MANCHEVSKI: WHY I LIKE WRITING AND HATE DIRECTING: NOTES OF A RECOVERING WRITER-DIRECTOR (Writer/Director, Scholar, Macedonia/USA) 11:30 am Coffee Break 11:45 am—1:15 pm Panel 1: WRITER–DIRECTOR’S SCREENPLAYS Ian W. Macdonald (University of Leeds, UK) SCREENWRITING AND SUBJECTIVITY Carmen Sofia Brenes (University of Los Andes, Chile) THE POETIC DENSITY OF THE STORY AS KEY ISSUE IN THE FILM NEGOTIATION BETWEEN WRITER, DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER Temenuga Trifonova (York University, Canada) THE WRITER’S SCREENPLAY AND THE WRITER/DIRECTOR’S SCREENPLAY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS Jarmo Lampela (Aalto University Helsinki, Finland) ENSEMBLE AS A SCRENWRITER – THEATRE GOES MOVIES Panel 2: AUTEUR–FILM Gabriel M. -

Translating the Exiled Self: Reflections on Translation and Censorship*

Intercultural Communication Studies XIV: 4 2005 Samar Attar TRANSLATING THE EXILED SELF: REFLECTIONS ON TRANSLATION AND CENSORSHIP* Samar Attar Independent Researcher Self-Translating and censorship Translators tend to select foreign literary texts for translation into their mother-tongue for different reasons. Sometimes, their selection is based on the fame of a certain writer among his or her own people, or for the awarding of a prestigious international prize to a writer, or on the recommendation of an authoritative figure: a scholar, a critic, or a publisher. At other times, however, the opposite can be true. A writer who is not known among his or her own people is translated into another language, because his or her writing subverts the values of the national tradition, or destroys certain clichés about other nations, or simply because his or her work appeals to the translator.1 But we should not entertain the illusion that literary translators are always free agents. Although their literary taste and ideology may play an important role in their selection of foreign texts they often have to consider the literary, political and economic climate of their time. They simply do not translate texts because they like them. They are very much aware of the fact that translation cannot be brought to a fruitful end unless other authoritative bodies support them, and unless a publisher is found at the end of the ordeal. In short, personal, literary, social, political and economic factors always play an important role in the selection and translation of a foreign text. Normally the literary translator, who selects or is helped in selecting a foreign text, is expected to be a master of at least two languages including his or her own native tongue. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Canadian Canada $7 Spring 2020 Vol.22, No.2 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SPRING 2020 VOL.22, NO.2 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA The Law & Order Issue The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style Peter Mitchell on Murdoch’s 200th ep Floyd Kane Delves into class, race & gender in legal PM40011669 drama Diggstown Help Producers Find and Hire You Update your Member Directory profile. It’s easy. Login at www.wgc.ca to get started. Questions? Contact Terry Mark ([email protected]) Member Directory Ad.indd 1 3/6/19 11:25 AM CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 22 No. 2 Spring 2020 Contents ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Cover Publisher Maureen Parker Diggstown Raises Kane To New Heights 6 Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Creator and showrunner Floyd Kane tackles the intersection of class, race, gender and the Canadian legal system as the Director of Communications groundbreaking CBC drama heads into its second season Lana Castleman By Li Robbins Editorial Advisory Board Michael Amo Michael MacLennan Features Susin Nielsen The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style 12 Simon Racioppa Rachel Langer With a solid background investigating and writing about true President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) crime, showrunner Petro Duszara and his team tell us why this Councillors series is resonating with viewers and lawmakers alike. Michael Amo (Atlantic) By Matthew Hays Marsha Greene (Central) Alex Levine (Central) Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) Murdoch Mysteries’ Major Milestone 16 Lienne Sawatsky (Central) Andrew Wreggitt (Western) Showrunner Peter Mitchell reflects on the successful marriage Design Studio Ours of writing and crew that has made Murdoch Mysteries an international hit, fuelling 200+ eps.