From the Workshop of JJ Abrams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Press Release

Elisabeth Moss as Peggy Olson Outstanding Lead Actor In A Drama Series Nashville • ABC • ABC Studios Connie Britton as Rayna James Breaking Bad • AMC • Sony Pictures Television Scandal • ABC • ABC Studios Bryan Cranston as Walter White Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope Downton Abbey • PBS • A Carnival / Masterpiece Co-Production Hugh Bonneville as Robert, Earl of Grantham Outstanding Lead Actor In A Homeland • Showtime • Showtime Presents, Miniseries Or A Movie Teakwood Lane Productions, Cherry Pie Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Keshet, Fox 21 Weintraub Productions in association with Damian Lewis as Nicholas Brody HBO Films House Of Cards • Netflix • Michael Douglas as Liberace Donen/Fincher/Roth and Trigger Street Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Inc. in association with Media Weintraub Productions in association with Rights Capital for Netflix HBO Films Kevin Spacey as Francis Underwood Matt Damon as Scott Thorson Mad Men • AMC • Lionsgate Television The Girl • HBO • Warner Bros. Jon Hamm as Don Draper Entertainment, GmbH/Moonlighting and BBC in association with HBO Films and Wall to The Newsroom • HBO • HBO Entertainment Wall Media Jeff Daniels as Will McAvoy Toby Jones as Alfred Hitchcock Parade's End • HBO • A Mammoth Screen Production, Trademark Films, BBC Outstanding Lead Actress In A Worldwide and Lookout Point in association Drama Series with HBO Miniseries and the BBC Benedict Cumberbatch as Christopher Tietjens Bates Motel • A&E • Universal Television, Carlton Cuse Productions and Kerry Ehrin -

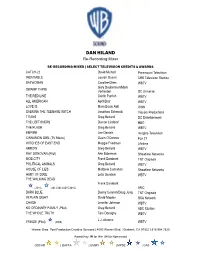

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS CATCH-22 David Michod Paramount Television INSATIABLE Lauren Gussis CBS Television Studios BATWOMAN Caroline Dries WBTV Gary Dauberman/Mark SWAMP THING Verheiden DC Universe THE RED LINE Cairlin Parrish WBTV ALL AMERICAN April Blair WBTV LOVE IS Mara Brock Akil OWN SABRINA THE TEENAGE WITCH Jonathan Schmock Viacom Productions TITANS Greg Berlanti DC Entertainment THE LEFTOVERS Damon Lindelof HBO THE FLASH Greg Berlanti WBTV EMPIRE Lee Daniels Imagine Television CINNAMON GIRL (TV Movie) Gavin O'Connor Fox 21 WITCHES OF EAST END Maggie Friedman Lifetime ARROW Greg Berlanti WBTV RAY DONOVAN (Pilot) Ann Biderman Showtime Networks MOB CITY Frank Darabont TNT Originals POLITICAL ANIMALS Greg Berlanti WBTV HOUSE OF LIES Matthew Carnahan Showtime Networks HART OF DIXIE Leila Gerstein WBTV THE WALKING DEAD Frank Darabont (2010) (2012/2014/2015/2016) AMC DARK BLUE Danny Cannon/Doug Jung TNT Originals IN PLAIN SIGHT David Maples USA Network CHASE Jennifer Johnson WBTV NO ORDINARY FAMILY (Pilot) Greg Berlanti ABC Studios THE WHOLE TRUTH Tom Donaghy WBTV J.J. Abrams FRINGE (Pilot) (2009) WBTV Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.7825 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS LIMELIGHT (Pilot) David Semel, WBTV HUMAN TARGET Jonathan E. Steinberg WBTV EASTWICK Maggie Friedman WBTV V (Pilot) Kenneth Johnson WBTV TERMINATOR: THE SARAH CONNER Josh Friedman CHRONICLES WBTV CAPTAIN -

SAG/AFTRA FILM (Partial List) Scare Package Supporting/ “Officer Ragen” Paper Street Pictures/ Aaron B. Koontz Dir. Human Pl

SAG/AFTRA FILM (Partial List) Scare Package Supporting/ “Officer Ragen” Paper Street Pictures/ Aaron B. Koontz Dir. Human Play Lead/ “James” Paper Street Pictures/ Mathieu Ricordi Dir. Little Woods Supporting/ "Man" Buffalo Picture House/ Nia DaCosta Dir. Elephone Man Lead/ "Bobby" Global Films/ Magarditch Halvadjian Dir. The Cable Men Starring/ "Barney" McShane Films/ Robin Conly Dir. Bitch (Short) Supporting/ "Will" Edgen Films/ Robin Conly Dir. Small Packages (Short) Starring/ "Porter" Grade A Films/ Anthony Faust Dir. An American In Texas Lead/ "Earl Doonan" Film Exchange/ Anthony Pedone Dir. Overcast (Short) Lead/ "Paulie" Atomic Productions/ Ben Adams Dir. Bomb City Supporting/ "Officer Chuck" 3rd Identity Films/ Jamie Brooks Dir. As Far As The Eye Can See Supporting/ "Bob Tanner" AFATECS LLC/ David Franklin Dir. Entity Starring/ "Eugene" Screengage LLC/ Michael Yurinko Dir. Human Play Lead/ "James" Paper Street Pictures/ Mathieu Ricordi Dir. Hard Reset 3-D Lead/ "Det. Wright" Buk Films/ Deepak Chetty Dir. The Doo Dah Man Supporting/ "Frank" Flatiron Pictures/ Claude Green Dir. Adventures of Pepper and Paula Lead/ "Ricky" The Nations/ Kevin & Robin Nations Dir. Sin City 2 Supporting/ "Tourist" Troublemaker/ Robert Rodriguez Dir. TELEVISION The Pact (Mini Series) Lead/ ”Drummer” Katara Studios/ Michael Phillips EP. Three Knee Deep (Mini Series) Lead/ "Jack" Luna/Luca Bercovichi Dir. The Leftovers Recurring/ "Sam" HBO/ Damon Lindelof EP. Queen of the South Co-Star/ "Donald Henry" USA/ Matthew Penn EP. From Dusk Til Dawn Co-Star/ "Chester" El Rey/ Eduardo Sanchez Dir. In An Instant Starring/ "Pete Soulis" ABC/ Todd Cobery Dir. American Crime Co-Star/ "Patrol Officer" ABC/ John Ridley Dir. -

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Title Director Screening Section Premiere Status

Title Director Screening Section Premiere Status An Evening With Sacred Bones Records Jacqueline Castel Special Events World Premiere Bernie Richard Linklater Special Events Best of Vimeo Shorts: Vimeo Loves Various Special Events Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me Drew DeNicola Special Events Casa de mi Padre Matt Piedmont Special Events Coffin Joe's "This Night I Will Possess Jose Mojica Marins Special Events Your Corpse" Girl Walk // All Day Jacob Krupnick Special Events Re: Generation Music Project Amir Bar Lev Special Events Adam Russell, Renga Special Events North American Premiere John Sear SXSW & The Alamo Drafthouse present: Special Events World Premiere Epic Meal Time The Oyster Princess (1919) Ernst Lubitsch Special Events with live score by Bee vs. Moth when you find me presented by Canon Bryce Dallas Howard Special Events U.S. Premiere George Dunning, Yellow Submarine (1968) Newly Restored (UK) Robert Balser, Special Events Jack Stokes Title Director Screening Section Premiere Status Phil Lord, 21 Jump Street Headliners World Premiere Christopher Miller BIG EASY EXPRESS Emmett Malloy Headliners World Premiere Decoding Deepak Gotham Chopra Headliners World Premiere Girls Lena Dunham Headliners World Premiere Killer Joe William Friedkin Headliners U.S. Premiere MARLEY Kevin Macdonald Headliners North American Premiere The Cabin in the Woods Drew Goddard Headliners World Premiere The Hunter Daniel Nettheim Headliners U.S. Premiere Blue Like Jazz Steve Taylor Narrative Spotlight World Premiere Crazy Eyes Adam Sherman Narrative Spotlight World Premiere Fat Kid Rules The World Matthew Lillard Narrative Spotlight World Premiere frankie go boom Jordan Roberts Narrative Spotlight World Premiere Hunky Dory Marc Evans Narrative Spotlight North American Premiere In Our Nature Brian Savelson Narrative Spotlight World Premiere Keyhole Guy Maddin Narrative Spotlight U.S. -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009 Annotations and citations (Law) -- Arizona. SHEPARD'S ARIZONA CITATIONS : EVERY STATE & FEDERAL CITATION. 5th ed. Colorado Springs, Colo. : LexisNexis, 2008. CORE. LOCATION = LAW CORE. KFA2459 .S53 2008 Online. LOCATION = LAW ONLINE ACCESS. Antitrust law -- European Union countries -- Congresses. EUROPEAN COMPETITION LAW ANNUAL 2007 : A REFORMED APPROACH TO ARTICLE 82 EC / EDITED BY CLAUS-DIETER EHLERMANN AND MEL MARQUIS. Oxford : Hart, 2008. KJE6456 .E88 2007. LOCATION = LAW FOREIGN & INTERNAT. Consolidation and merger of corporations -- Law and legislation -- United States. ACQUISITIONS UNDER THE HART-SCOTT-RODINO ANTITRUST IMPROVEMENTS ACT / STEPHEN M. AXINN ... [ET AL.]. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y. : Law Journal Press, c2008- KF1655 .A74 2008. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Consumer credit -- Law and legislation -- United States -- Popular works. THE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION GUIDE TO CREDIT & BANKRUPTCY. 1st ed. New York : Random House Reference, c2006. KF1524.6 .A46 2006. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Construction industry -- Law and legislation -- Arizona. ARIZONA CONSTRUCTION LAW ANNOTATED : ARIZONA CONSTITUTION, STATUTES, AND REGULATIONS WITH ANNOTATIONS AND COMMENTARY. [Eagan, Minn.] : Thomson/West, c2008- KFA2469 .A75. LOCATION = LAW RESERVE. 1 Court administration -- United States. THE USE OF COURTROOMS IN U.S. DISTRICT COURTS : A REPORT TO THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE ON COURT ADMINISTRATION & CASE MANAGEMENT. Washington, DC : Federal Judicial Center, [2008] JU 13.2:C 83/9. LOCATION = LAW GOV DOCS STACKS. Discrimination in employment -- Law and legislation -- United States. EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION : LAW AND PRACTICE / CHARLES A. SULLIVAN, LAUREN M. WALTER. 4th ed. Austin : Wolters Kluwer Law & Business ; Frederick, MD : Aspen Pub., c2009. KF3464 .S84 2009. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. -

The Storyworld Dynamics of Supernatural

PRODUCTIONS / MARKETS / STRATEGIES ANGELS, DEMONS AND WHATEVER COMES NEXT: THE STORYWORLD DYNAMICS OF SUPERNATURAL FLORENT FAVARD Name Florent Favard the series with an analysis of its writing, production and Academic centre IECA, Université de Lorraine reception contexts, and divides the long-running series into E-mail address [email protected] four eras, each defined by a specific showrunner. It starts by exploring the context of the series’ creation, before KEYWORDS cataloguing the shifting dynamics of the storyworld during Storyworld; narratology; writing; ethos; showrunner. the four eras: the ‘stealth teleological’ approach of series creator Eric Kripke; the complex reconfigurations of the Sera Gamble era; the ‘mythology reboot’ of the Jeremy ABSTRACT Carver era; and the ever-increasing stakes and expansionist This paper explores the narrative dynamics of the fantasy dynamics of the Andrew Dabb era. The aim of this paper television series Supernatural (2005-) in order to better is to show how ‘periodising’ a long-running series by using understand how this particular program has become a close-reading and studying the dynamics of a storyworld backbone of The CW network. Combining formal and can expand and complete analysis focused on audiences contextual narratologies, it blends a close-reading of and the genesis of the text. 19 SERIES VOLUME IV, Nº 2, WINTER 2018: 19-26 DOI https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2421-454X/8164 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TV SERIAL NARRATIVES ISSN 2421-454X INVESTIGATING THE CW PRODUCTIONS / MARKETS / STRATEGIES > FLORENT FAVARD ANGELS, DEMONS AND WHATEVER COMES NEXT: THE STORYWORLD DYNAMICS OF SUPERNATURAL The Apocalypse has just been averted. -

MICHAEL BONVILLAIN, ASC Director of Photography

MICHAEL BONVILLAIN, ASC Director of Photography official website FEATURES (partial list) OUTSIDE THE WIRE Netflix Dir: Mikael Håfström AMERICAN ULTRA Lionsgate Dir: Nima Nourizadeh Trailer MARVEL ONE-SHOT: ALL HAIL THE KING Marvel Entertainment Dir: Drew Pearce ONE NIGHT SURPRISE Cathay Audiovisual Global Dir: Eva Jin HANSEL & GRETEL: WITCH HUNTERS Paramount Pictures Dir: Tommy Wirkola Trailer WANDERLUST Universal Pictures Dir: David Wain ZOMBIELAND Columbia Pictures Dir: Ruben Fleischer Trailer CLOVERFIELD Paramount Pictures Dir: Matt Reeves A TEXAS FUNERAL New City Releasing Dir: W. Blake Herron THE LAST MARSHAL Filmtown Entertainment Dir: Mike Kirton FROM DUSK TILL DAWN 3 Dimension Films Dir: P.J. Pesce AMONGST FRIENDS Fine Line Features Dir: Rob Weiss TELEVISION (partial list) PEACEMAKER (Season 1) HBO Max DIR: James Gunn WAYS & MEANS (Season 1) CBS EP: Mike Murphy, Ed Redlich HAP AND LEONARD (Season 3) Sundance TV, Netflix EP: Jim Mickle, Nick Damici, Jeremy Platt Trailer WESTWORLD (Utah; Season 1, 4 Episodes.) Bad Robot, HBO EP: Lisa Joy, Jonathan Nolan CHANCE (Pilot) Fox 21, Hulu EP: Michael London, Kem Nunn, Brian Grazer Trailer THE SHANNARA CHRONICLES MTV EP: Al Gough, Miles Millar, Jon Favreau (Pilot & Episode 102) FROM DUSK TIL DAWN (Season 1) Entertainment One EP: Juan Carlos Coto, Robert Rodriguez COMPANY TOWN (Pilot) CBS EP: Taylor Hackford, Bill Haber, Sera Gamble DIR: Taylor Hackford REVOLUTION (Pilot) NBC EP: Jon Favreau, Eric Kripke, Bryan Burk, J.J. Abrams DIR: Jon Favreau UNDERCOVERS (Pilot) NBC EP: J.J. Abrams, Bryan Burk, Josh Reims DIR: J.J. Abrams OUTLAW (Pilot) NBC EP: Richard Schwartz, Amanda Green, Lukas Reiter DIR: Terry George *FRINGE (Pilot) Fox Dir: J.J. -

Read Doc > Revolution TV Series

7HGHXQ8UH98T / Kindle < Revolution TV Series - Unabridged Guide Revolution TV Series - Unabridged Guide Filesize: 3.39 MB Reviews This is actually the best book i actually have go through right up until now. It generally will not price an excessive amount of. I discovered this book from my dad and i suggested this book to understand. (Norma Carroll) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 3WH6M1VPVEKQ Doc # Revolution TV Series - Unabridged Guide REVOLUTION TV SERIES - UNABRIDGED GUIDE Tebbo. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Paperback. 40 pages. Dimensions: 8.7in. x 5.8in. x 0.2in.Complete, Unabridged Guide to Revolution (TV series). Get the information you need--fast! This comprehensive guide oers a thorough view of key knowledge and detailed insight. Its all you need. Heres part of the content - you would like to know it all Delve into this book today! . : The series focuses on the Matheson family, who possess a special flash drive that is the key to not only finding out what happened fieen years ago, but also a possible way to reverse its eects. It was such a great premise for a series that it was just that feeling of the misery that youd feel if you had a chance to be part of that and didnt take advantage of it. In the summer of 2012, NBC had a voting campaign on Revolutions Facebook page where visitors could vote for which American city should have an advance screening of the series pilot in early September. Verne Gay of the Newsday however gave the premiere a neutral review saying Theres an almost overwhelming been-there-seen-that feel to the pilot, which doesnt really oer any suggestion of well, you havent seen this. -

ALLISA SWANSON Costume Designer

ALLISA SWANSON Costume Designer https://www.allisaswanson.com/ Selected Television: FIREFLY LANE (Pilot, S1&2) – Netflix / Brightlight Pictures – Maggie Friedman, creator TURNER & HOOCH (Pilot, S1) – 20th Century Fox / Disney+ – Matt Nix, writer – McG, pilot dir. ALIVE (Pilot) – CBS Studios – Uta Briesewitz, director ANOTHER LIFE (Pilot, S1) – Netflix / Halfire Entertainment – Aaron Martin, creator ONCE UPON A TIME (S7 eps. 716-722) – Disney/ABC TV – Edward Kitsis & Adam Horowitz, creators *NOMINATED, Excellence in Costume Design in TV – Sci-Fi/Fantasy - CAFTCAD Awards THE 100 (S3 + S4) – Alloy Entertainment / Warner Bros. / The CW – Jason Rothenberg, creator DEAD OF SUMMER (Pilot, S1) Disney / ABC / Freeform – Ian Goldberg, Adam Horowitz & Eddy Kitsis, creators MORTAL KOMBAT: LEGACY (Mini Series) – Warner Bros. – Kevin Tancharoen, director BEYOND SHERWOOD (TV Movie) – SyFy / Starz – Peter DeLuise, director KNIGHTS OF BLOODSTEEL (Mini-Series) – SyFy / Reunion Pictures – Phillip Spink, director SEA BEAST (TV Movie) – SyFy / NBC Universal TV – Paul Ziller, director EDGEMONT (S1 - S5) – CBC / Water Street Pictures / Fox Family Channel – Ian Weir, creator Selected Features: COFFEE & KAREEM – Netflix / Pacific Electric Picture Company – Michael Dowse, director GOOD BOYS (Addt’l Photo. )– Universal / Good Universe / Point Grey Pictures – Gene Stupnitsky, dir. DARC – Netflix / JRN Productions – Nick Powell, director THE UNSPOKEN – Lighthouse Pictures / Paladin – Sheldon Wilson, director THE MARINE: HOMEFRONT – WWE Studios – Scott Wiper, director ICARUS/THE KILLING MACHINE – Cinetel Films – Dolph Lundgren, director SPACE BUDDIES – Walt Disney Home Entertainment – Robert Vince, director DANCING TREES – NGN Productions – Anne Wheeler, director THE BETRAYED – MGM – Amanda Gusack, director SNOW BUDDIES – Walt Disney Home Entertainment – Robert Vince, director BLONDE & BLONDER – Rigel Entertainment – Bob Clark, director CHESTNUT: HERO OF CENTRAL PARK – Miramax / Keystone Entertainment – Robert Vince, dir.