O Tannenbaum Presents Arranged by Wynton Marsalis Full Score

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrating Diversity

Celebrating Diversity - Overcoming Adversity part 2: Marcus Roberts by Valerie Etienne- Leveille Marcus Roberts, 1963 – present: Musician, composer, arranger Marcus Roberts was born on August 7th, 1963 in Jacksonville, Florida. He grew up listening to his mother’s gospel singing and the music of the local church. These exposures to music had a lasting impact on his musical style. Marcus began teaching himself to play the piano at the age of five after losing his sight due to glaucoma (1)(2). At the age of ten in 1973, Marcus entered the Florida School for the Deaf and Blind (FSDB). Marcus did not receive formal piano lessons until he was 12 but he progressed very quickly through hard work and good teachers (2). In the 10th grade, he was mainstreamed in the local St. Augustine high school in the morning, and he went to FSDB in the afternoon for music (3). After graduating from FSDB, Marcus went on to study classical piano at the Florida State University (FSU) with Leonidas Lipovetsky (2). Marcus has won many awards and competitions over the years, but the one that is most personally meaningful to him is the Helen Keller Award for Personal Achievement. Marcus Roberts is known for his ability to blend the jazz and classical idioms, which focus on specific technical features, to create something new. He is also well-known for his development of an entirely new approach to jazz trio performance (2). His recordings reflect his artistic versatility and include pieces such as solo piano, duets, trio arrangements of jazz standards, large ensembles, and symphony orchestra (3). -

Kimmel Center Announces 2019/20 Jazz Season

Tweet it! JUST ANNOUNCED! @KimmelCenter 19/20 #Jazz Season features a fusion of #tradition and #innovation with genre-bending artists, #Grammy Award-winning musicians, iconic artists, and trailblazing new acts! More info @ kimmelcenter.org Press Contact: Lauren Woodard Jessica Christopher 215-790-5835 267-765-3738 [email protected] [email protected] KIMMEL CENTER ANNOUNCES 2019/20 JAZZ SEASON STAR-STUDDED LINEUP INCLUDES MULTI-GRAMMY® AWARD-WINNING CHICK COREA TRILOGY, GENRE-BENDING ARTISTS BLACK VIOLIN AND BÉLA FLECK & THE FLECKTONES, GROUNDBREAKING SOLOISTS, JAZZ GREATS, RISING STARS & MORE! MORE THAN 100,000 HAVE EXPERIENCED JAZZ @ THE KIMMEL ECLECTIC. IMMERSIVE. UNEXPECTED. PACKAGES ON SALE TODAY! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, April 30, 2019) –– The Kimmel Center Cultural Campus announces its eclectic 2019/20 Jazz Season, featuring powerhouse collaborations, critically-acclaimed musicians, and culturally diverse masters of the craft. Offerings include a fusion of classical compositions with innovative hip-hop sounds, Grammy® Award-winning performers, plus versatile arrangements rooted in tradition. Throughout the season, the varied programming showcases the evolution of jazz – from the genre’s legendary history in Philadelphia to the groundbreaking new artists who continue to pioneer music for future generations. The 2019/20 season will kick off on October 11 with pianist/composer hailed as “the genius of the modern piano,” Marcus Roberts & the Modern Jazz Generation, followed on October 27 -

Disco Reed Détaillée

20-21 décembre 2000, New York graphie disco HAPPINESS Plenty Swing, Plenty Soul Eric Reed (p) Marcus Printup (tp) Wycliffe Gordon (tb) Eric REDD Guy Reynard et Yves Sportis Wes Anderson (as) Walter Blanding (cl) OUS FAISONS ici état des enregistrements d’Eric Reed en leader et coleader. L’index en Rodney Green (dm) sideman permet de rendre compte de la grande curiosité d’Eric Reed. Il est un 1. Overture Renato Thomas (perc) Nsolide leader mais également un grand accompagnateur prisé par ses pairs. Eric 2. Maria Reed possède un univers très large dans le jazz, dans son sens culturel, la musique 3.Hello, Young Lovers d’inspiration religieuse et le blues étant également omniprésent dans son expression. 4. Pure Imagination Rappelons qu’une discographie présente l’état des publications sur disque. Chaque 5. 42nd Street session est classée chronologiquement, présente la date et le lieu d’enregistrement, le(s) 6.Send in the Clowns titre(s) des albums où elle se trouve gravée, énumère les musiciens, les titres des morceaux, 7. My Man's Gone Now/Gone, enfin la référence des albums en LP ou CD. Nous avons retenu en priorité les éditions Gone, Gone cohérentes. Les livrets/couvertures en illustration constituent de bons repères. Rappelons que 8. Nice Work If You Can Get It 9. You'll Never Walk Alone l’index n’est pas une totalisation de toutes les éditions, mais le fil continu, en CD ou à défaut 10. I Got Rhythm en LP. 1. Happiness 11. Finale (Last Trip) 2. Three Dances: Island Grind- Pour cette discographie (méthode Jazz Hot), nous avons consulté d’excellentes sources ❚■● Impulse! 12592 discographiques, comme la Jazz Discography de Walter Bruyninckx, sur internet Latin Bump-Boogie www.jazzdisco.org/eric-reed/discography et bien sûr les disques eux-mêmes. -

Kimmel Center Cultural Campus Kicks Off 2019/20 Jazz Season with Award-Winning Pianist & Composer Marcus Roberts and the M

Tweet It! The @KimmelCenter 2019/20 jazz season kicks off with the ‘genius of the modern piano’ Marcus Roberts and The Modern Jazz Generation on 10/11. More info @ kimmelcenter.org Press Contact: Lauren Woodard Jessica Christopher 215-790-5835 267-765-3738 [email protected] [email protected] KIMMEL CENTER CULTURAL CAMPUS KICKS OFF 2019/20 JAZZ SEASON WITH AWARD-WINNING PIANIST & COMPOSER MARCUS ROBERTS AND THE MODERN JAZZ GENERATION OCTOBER 11, 2019 In conjunction with 2019 Living Legacy Jazz Award Presented by PECO & Jazz Philadelphia Summit “His combination of talent, ambition, discipline, stylistic openness and resourcefulness suggest that he is a remarkable musician—perhaps even a Phenomenon…” – JAZZ TIMES “He's a virtuoso, a monster musician.” –WYNTON MARSALIS, FOR 60 MINUTES “Pianist Marcus Roberts is known for many things: a genius skill… an immense love of the blues, technological innovations in regard to composing for the blind, and a soulful sense of tradition and invention."- A.D. AMOROSI, THE PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, September 9, 2019) – Hailed as ‘the genius of the modern piano,’ the Kimmel Center Cultural Campus kicks off the 2019/20 Jazz Season with Marcus Roberts and the Modern Jazz Generation Band on Friday, October 11, 2019 at 8:00 p.m. at the Perelman Theater. “Marcus Roberts is truly a revelation in the modern jazz era, and we are delighted to have him serve as the inauguration of this year’s stellar jazz season,” said Ed Cambron, Chief Operating Officer and Executive Vice President of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. -

It's All Good

SEPTEMBER 2014—ISSUE 149 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM JASON MORAN IT’S ALL GOOD... CHARLIE IN MEMORIAMHADEN 1937-2014 JOE • SYLVIE • BOBBY • MATT • EVENT TEMPERLEY COURVOISIER NAUGHTON DENNIS CALENDAR SEPTEMBER 2014 BILLY COBHAM SPECTRUM 40 ODEAN POPE, PHAROAH SANDERS, YOUN SUN NAH TALIB KWELI LIVE W/ BAND SEPT 2 - 7 JAMES CARTER, GERI ALLEN, REGGIE & ULF WAKENIUS DUO SEPT 18 - 19 WORKMAN, JEFF “TAIN” WATTS - LIVE ALBUM RECORDING SEPT 15 - 16 SEPT 9 - 14 ROY HARGROVE QUINTET THE COOKERS: DONALD HARRISON, KENNY WERNER: COALITION w/ CHICK COREA & THE VIGIL SEPT 20 - 21 BILLY HARPER, EDDIE HENDERSON, DAVID SÁNCHEZ, MIGUEL ZENÓN & SEPT 30 - OCT 5 DAVID WEISS, GEORGE CABLES, MORE - ALBUM RELEASE CECIL MCBEE, BILLY HART ALBUM RELEASE SEPT 23 - 24 SEPT 26 - 28 TY STEPHENS (8PM) / REBEL TUMBAO (10:30PM) SEPT 1 • MARK GUILIANA’S BEAT MUSIC - LABEL LAUNCH/RECORD RELEASE SHOW SEPT 8 GATO BARBIERI SEPT 17 • JANE BUNNETT & MAQUEQUE SEPT 22 • LOU DONALDSON QUARTET SEPT 25 LIL JOHN ROBERTS CD RELEASE SHOW (8PM) / THE REVELATIONS SALUTE BOBBY WOMACK (10:30PM) SEPT 29 SUNDAY BRUNCH MORDY FERBER TRIO SEPT 7 • THE DIZZY GILLESPIE™ ALL STARS SEPT 14 LATE NIGHT GROOVE SERIES THE FLOWDOWN SEPT 5 • EAST GIPSY BAND w/ TIM RIES SEPT 6 • LEE HOGANS SEPT 12 • JOSH DAVID & JUDAH TRIBE SEPT 13 RABBI DARKSIDE SEPT 19 • LEX SADLER SEPT 20 • SUGABUSH SEPT 26 • BROWN RICE FAMILY SEPT 27 Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps with Hutch or different things like that. like things different or Hutch with sometimes. -

Download the Blood on the Fields Playbill And

Thursday–Saturday Evening, February 21 –23, 2013, at 8:00 Wynton Marsalis, Managing & Artistic Director Greg Scholl, Executive Director Bloomberg is the Lead Corporate Sponsor of this performance. BLOOD ON THE FIELDS JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER ORCHESTRA WYNTON MARSALIS, Music Director, Trumpet RYAN KISOR, Trumpet KENNY RAMPTON, Trumpet MARCUS PRINTUP, Trumpet VINCENT GARDNER, Trombone, Tuba CHRIS CRENSHAW, Trombone ELLIOT MASON, Trombone SHERMAN IRBY, Alto & Soprano Saxophones TED NASH, Alto & Soprano Saxophones VICTOR GOINES, Tenor & Soprano Saxophones, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet WALTER BLANDING, Tenor & Soprano Saxophones CARL MARAGHI, Baritone Saxophone, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet ELI BISHOP, Guest Soloist, Violin ERIC REED, Piano CARLOS HENRIQUEZ, Bass ALI JACKSON, Drums Featuring GREGORY PORTER, Vocals KENNY WASHINGTON, Vocals PAULA WEST, Vocals There will be a 15-minute intermission for this performance. Please turn off your cell phones and other electronic devices. Jazz at Lincoln Center thanks its season sponsors: Bloomberg, Brooks Brothers, The Coca-Cola Company, Con Edison, Entergy, HSBC Bank, Qatar Airways, The Shops at Columbus Circle at Time Warner Center, and SiriusXM. MasterCard® is the Preferred Card of Jazz at Lincoln Center. Qatar Airways is a Premier Sponsor and Official Airline Partner of Jazz at Lincoln Center. This concert is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. ROSE THEATER JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER’S FREDERICK P. ROSE HALL jalc.org PROGRAM JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER 25TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON HONORS Since Jazz at Lincoln Center’s inception on August 3, 1987, when Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts initiated a three-performance summertime series called “Classical Jazz,” the organization has been steadfast in its commitment to broadening and deepening the public’s awareness of and participation in jazz. -

Wycliffe Gordon at GRU

World-renownedtrombonist Practiceby Jim Garvey makes Wycliffehas reached Gordon the pinnacle ofand music now success he is Perfect with the sharing his expertise music department at GRU. HOW DO YOU GET TO GRU’S MAXWELL THEATRE? PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE. At least that’s how Wycliffe Gordon, the best jazz trombonist in the world, got there. After years of teaching at Juilliard and the Manhattan School of Music, touring the world with Wynton Marsalis and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, performing with symphony orchestras, recording, com- posing, arranging, giving workshops, lectures and master classes, Gordon was finally offered the job he’s been preparing for all these years: artist-in-residence in GRU’s Department of Music. “I’ve come full circle, teaching at a university in my own town after teaching all over the world,” Gordon says. “I’m from here. My high school, Butler High School, is here. My mom lives here. Coming to GRU is Jazz trombonist and composer Wycliffe Gordon performs on stage at like icing on the cake.” u Davidson Fine Arts School in 2008. 32 • Augusta April 2015 April 2015 Augusta • 33 “...a full, powerful tone, slurring then slippingsliding and growling BUT TRADING IN NEW YORK CITY FOR HEPHZIBAH? His fame is never on display. With his round, boyish face and twinkling eyes, “I had a place in New York for 15 “During his solo, Gordon locked in Currier, an opera singer who has sung he’s more playful imp than musical phenom. Still phenom is what he is. years. I’ve had enough pretty much. -

Gettysburg Symphony Orchestra

he Serving Baltimore/Washington/Annapolis . J January/February 2003 Circulation: 27,000 Johns Hopkins News Russian pianist The- Baltimore Alexander Shtarkman solp with the Shostakovich's in Hail Peabody Lady Macbeth of Dedication Mtsensk >age 3 Orchestra guest conducted by Leon Fleisher -jf V V**5. Yuri Temirkanov programs Russian composer with the Baltimon Symphon S B U R G A city-wide celebration Lori Hultgrei* with Peabody Symphony Orchestra Page 7 Peabodv Chamber Opera presents Berlin/Munich double bill Page 8 Young Dance classes at Preparatory Page 16 2 Peabody News January/February 2003 [ERNO N CULTURAL DISTRICT * MOUNT VERNON CULTURAL DISTRICT • MOUNT VERNON CULTURAL DISTRICT * MOUNi #19 FIND YOUR KNIGHT IN SHINING ARMOR jf *" For 99 other fun things to do, visit www.mvcd.org i MOUNT VERNON CULTURAL DISTRICT NEIGHBORHOOD Baltimore School for the Arts * Basilica of the Assumption * Center Stage * Contemporary Museum * Garrett Jacobs Mansion 100 * Enoch Pratt Free Library * Eubie Blake National Jazz Institute and Cultural Center * The George Peabody Library * Maryland •THINGS TO DO! I Historical Society * The Peabody Institute * The Walters Art Museum January/February 2003 Peabody News 3 1 John. Js * Hopkins : Peabody News lifts I The Award Winning wamm Newspaper of the Baltimore/ Washington Cultural Corridor Published by the Peabody Richard Goode awarded Conservatory of Music, George Peabody Medal Baltimore. First he played a magical recital. Then at the end of his October 29 program, Richard Goode was presented with the Circulation: -

2021 Program

This organization is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Arts and the SC Arts Commission. Thirteen Years of Joye in Aiken In this year of change, when it has sometimes seemed as if nothing might ever be normal again, one thing that has not changed is the importance of the arts in our lives. Especially where sources of hope and inspiration are few, the arts retain their power to energize and refresh us. And so it is with even greater pleasure than usual that we welcome you (digitally, to be sure) to the 13th Annual Joye in Aiken Festival and Outreach Program. Though COVID-19 has forced us to rethink timeframes, formats and venues in the interest of ensuring the safety of our community and our artists, we have embraced those challenges as opportunities. If a single Festival week presented dangers, could we spread the events out to allow for responses to changing conditions? If it wasn’t possible to hold an event indoors, could we hold it outdoors? With those questions and a thousand others answered, we are proud to present to you a Festival that is necessarily different in many respects, but that is no less exciting. And because it’s so central to our mission, we’re especially proud to introduce to you an important new dimension of our Outreach Program. With COVID making it impossible for us to present our usual Kidz Bop and Young People’s Concerts, we turned to our nationally-known artists for help. And their solution was perfect: two engaging series of instructional videos designed specifically for the children of Aiken County by these world-class musicians. -

Jazz Faculty and Friends: an Evening of Great Music

Kennesaw State University Upcoming Music Events Tuesday, November 18 Kennesaw State University Jazz Combos 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall School of Music Wednesday, November 19 Kennesaw State University Wind Ensemble and Concert Band presents 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Thursday, November 20 Kennesaw State University Gospel Choir 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Kennesaw State University Saturday, November 22 Kennesaw State University Jazz Faculty and Friends Opera Gala 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Monday, November 24 Kennesaw State University Percussion Ensemble 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Tuesday, December 2 Kennesaw State University Choral Ensembles Holiday Concert 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Monday, November 17, 2008 8:00 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center Concert Hall For the most current information, please visit http://www.kennesaw.edu/arts/events/ Twenty-third Concert of the 2008-2009 season Kennesaw State University Justin Varnes drums School of Music Born in Jacksonville, Florida, Justin Varnes studied music at the Monday, November 17, 2008 University of North Florida. After a brief stint with the Noel Freidline 8:00 pm Quintet, Mr. Varnes relocated to New York City to pursue a master's Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center degree in jazz studies at the New School. In New York, Justin toured for six years with vocalist Phoebe Snow, with whom he performed on the Performance Hall Roseanne Barr Show, as well as National Public Radio's "World Cafe" (he would later perform on "World Cafe" with pop group "Five for Fighting"). -

Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra

CAL PERFORMANCE PRESENTS ABOUT THE ARTISTS Tuesday, September 22, 2009, 8pm The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra (JLCO), Freddie Hubbard, Charles McPherson, Marcus Zellerbach Hall composed of 15 of today’s finest jazz soloists and en- Roberts, Geri Allen, Eric Reed, Wallace Roney semble players, has been the Jazz at Lincoln Center and Christian McBride, as well as from current and resident orchestra for over 13 years. Featured in all former JLCO members Wynton Marsalis, Wycliffe Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra aspects of Jazz at Lincoln Center’s programming, Gordon, Ted Nash and Ron Westray. Over the last the remarkably versatile JLCO performs and leads few years, the JLCO has performed collaborations with educational events in New York, across the United with many of the world’s leading symphony or- States and around the world; in concert halls, chestras, including the New York Philharmonic, Wynton Marsalis dance venues, jazz clubs, public parks, river boats the Russian National Orchestra, the Berlin and churches; and with symphony orchestras, bal- Philharmonic, the Boston, Chicago, and London let troupes, local students and an ever-expanding symphonies, and the Orchestra Esperimentale in roster of guest artists. Education is a major part São Paolo, Brazil. In 2006, the JLCO collaborated Wynton Marsalis music director, trumpet of Jazz at Lincoln Center’s mission, and its educa- with Ghanaian drum collective Odadaa!, led by James Zollar trumpet tional activities are coordinated with concert and Yacub Addy, to perform Congo Square, a compo- Ryan Kisor trumpet JLCO tour programming. sition Mr. Marsalis and Mr. Addy co-wrote and Marcus Printup trumpet These programs, many of which feature JLCO dedicated to Mr. -

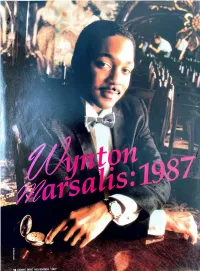

1987 DOWN BEAT 17 Melodic, Blues-Based Invention of Ornette Coleman, Or the Doing, They Weren't Interested in His Enthusiasm

By Stanley Crouch Editor's note: We last interviewed Wynton Marsalis in 1984. Since tha.t time his popularity and notoriety have, if anything, grown and, as can be seen in the following interview, he views his position with the utmost responsibility and seriousness. It is interesting to note that despite-or perhaps because of-his popularity, the trumpeter has become the focal point in a critical controversy waged over questions of innovation vs. imitation. In addressing these questions, and those concerning his success, the importance of knowledge and technical preparation for a career in music, and the role of jazz education, he brings the same carefully considered articulation which identifies his musical creativity. • • • STANLEY CROUCH: Do you hove anything to soy before we humility to one day add to the already noble tradition that first begin, on opening statement? took wing in the Crescent City. It still befuddles me that all the drums Jeff Watts is playing has been overlooked. He's isolating WYNTON MARSALIS: Yes. I want to make clear some things I aspects of time in fluctuating but cohesive parts, each of which think have been misunderstood. Were I playing the level of horn I swings, and his skill at thematic development through his aspire to, I don't think I would be giving interviews; I would be instrument within the form is nasty. But then he is The Tainish making all my statements from the bandstand. But at this point, One. Marcus Roberts is so superior in true country soul to any words allow me more precision and clarity.