The Scudamore Stirrups, and the Family's Use of Personal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geoffrey De Mandeville a Study of the Anarchy

GEOFFREY DE MANDEVILLE A STUDY OF THE ANARCHY By John Horace Round CHAPTER I. THE ACCESSION OF STEPHEN. BEFORE approaching that struggle between King Stephen and his rival, the Empress Maud, with which this work is mainly concerned, it is desirable to examine the peculiar conditions of Stephen's accession to the crown, determining, as they did, his position as king, and supplying, we shall find, the master-key to the anomalous character of his reign. The actual facts of the case are happily beyond question. From the moment of his uncle's death, as Dr. Stubbs truly observes, "the succession was treated as an open question." * Stephen, quick to see his chance, made a bold stroke for the crown. The wind was in his favour, and, with a handful of comrades, he landed on the shores of Kent. 2 His first reception was not encouraging : Dover refused him admission, and Canterbury closed her gates. 8 On this Dr. Stubbs thus comments : " At Dover and at Canterbury he was received with sullen silence. The men of Kent had no love for the stranger who came, as his predecessor Eustace had done, to trouble the land." * But "the men of Kent" were faithful to Stephen, when all others forsook him, and, remembering this, one would hardly expect to find in them his chief opponents. Nor, indeed, were they. Our great historian, when he wrote thus, must, I venture to think, have overlooked the passage in Ordericus (v. 110), from which we learn, incidentally, that Canterbury and Dover were among those fortresses which the Earl of Gloucester held by his father's gift. -

Revisiting the Monument Fifty Years Since Panofsky’S Tomb Sculpture

REVISITING THE MONUMENT FIFTY YEARS SINCE PANOFSKY’S TOMB SCULPTURE EDITED BY ANN ADAMS JESSICA BARKER Revisiting The Monument: Fifty Years since Panofsky’s Tomb Sculpture Edited by Ann Adams and Jessica Barker With contributions by: Ann Adams Jessica Barker James Alexander Cameron Martha Dunkelman Shirin Fozi Sanne Frequin Robert Marcoux Susie Nash Geoffrey Nuttall Luca Palozzi Matthew Reeves Kim Woods Series Editor: Alixe Bovey Courtauld Books Online is published by the Research Forum of The Courtauld Institute of Art Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 0RN © 2016, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. ISBN: 978-1-907485-06-0 Courtauld Books Online Advisory Board: Paul Binski (University of Cambridge) Thomas Crow (Institute of Fine Arts) Michael Ann Holly (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute) Courtauld Books Online is a series of scholarly books published by The Courtauld Institute of Art. The series includes research publications that emerge from Courtauld Research Forum events and Courtauld projects involving an array of outstanding scholars from art history and conservation across the world. It is an open-access series, freely available to readers to read online and to download without charge. The series has been developed in the context of research priorities of The Courtauld which emphasise the extension of knowledge in the fields of art history and conservation, and the development of new patterns of explanation. For more information contact [email protected] All chapters of this book are available for download at courtauld.ac.uk/research/courtauld-books-online Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of images reproduced in this publication. -

Drawing After the Antique at the British Museum

Drawing after the Antique at the British Museum Supplementary Materials: Biographies of Students Admitted to Draw in the Townley Gallery, British Museum, with Facsimiles of the Gallery Register Pages (1809 – 1817) Essay by Martin Myrone Contents Facsimile, Transcription and Biographies • Page 1 • Page 2 • Page 3 • Page 4 • Page 5 • Page 6 • Page 7 Sources and Abbreviations • Manuscript Sources • Abbreviations for Online Resources • Further Online Resources • Abbreviations for Printed Sources • Further Printed Sources 1 of 120 Jan. 14 Mr Ralph Irvine, no.8 Gt. Howland St. [recommended by] Mr Planta/ 6 months This is probably intended for the Scottish landscape painter Hugh Irvine (1782– 1829), who exhibited from 8 Howland Street in 1809. “This young gentleman, at an early period of life, manifested a strong inclination for the study of art, and for several years his application has been unremitting. For some time he was a pupil of Mr Reinagle of London, whose merit as an artist is well known; and he has long been a close student in landscape afer Nature” (Thom, History of Aberdeen, 1: 198). He was the third son of Alexander Irvine, 18th laird of Drum, Aberdeenshire (1754–1844), and his wife Jean (Forbes; d.1786). His uncle was the artist and art dealer James Irvine (1757–1831). Alexander Irvine had four sons and a daughter; Alexander (b.1777), Charles (b.1780), Hugh, Francis, and daughter Christian. There is no record of a Ralph Irvine among the Irvines of Drum (Wimberley, Short Account), nor was there a Royal Academy student or exhibiting or listed artist of this name, so this was surely a clerical error or misunderstanding. -

The Scropfs of Bolton and of Masham

THE SCROPFS OF BOLTON AND OF MASHAM, C. 1300 - C. 1450: A STUDY OF A kORTHERN NOBLE FAMILY WITH A CALENDAR OF THE SCROPE OF BOLTON CARTULARY 'IWO VOLUMES VOLUME II BRIGh h VALE D. PHIL. THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY MAY 1987 VOLUME 'IWO GUIDE '10 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CALENDAR OF THE SCROPE OF BOLTON CARTULARY 1 GUIDE '10 Call'ENTS page 1. West Bolton 1 2. Little Bolton or Low Bolton 7, 263 3. East Bolton or Castle Bolton 11, 264 4. Preston Under Scar 16, 266 5. Redmire 20, 265, 271 6. Wensley 24, 272 7. Leyburn 38, 273 8. Harmby 43, 274, 276 9. Bellerby 48, 275, 277 10. Stainton 57, 157 11. Downholme 58, 160 12. Marske 68, 159 13. Richmond 70, 120, 161 14. Newton Morrell 79, 173 15. rolby 80, 175 16. Croft on Tees 81, 174 17. Walmire 85 18. Uckerby 86, 176 19. Bolton on Swale 89, 177 20. Ellerton on Swale 92, 178, 228, 230 21. Thrintoft 102, 229 22. Yafforth 103, 231 23. Ainderby Steeple 106, 232 24. Caldwell 108, 140, 169 25. Stanwick St. John 111, 167 26. Cliff on Tees 112 27. Eppleby 113, 170 28. Aldbrough 114, 165 29. Manfield 115, 166 30. Brettanby and Barton 116, 172 31. Advowson of St. Agatha's, Easby 122, 162 32. Skeeby 127, 155, 164 33. Brampton on Swale 129, 154 34. Brignall 131, 187 35. Mbrtham 137, 186 36. Wycliffe 139, 168 37. Sutton Howgrave 146, 245 38. Thornton Steward 150, 207 39. Newbiggin 179, 227 40. -

Collections for a History of Staffordshire, 1883

COLLECTIONS StaffordshireFOE A HISTORY 0F , 0 STAFFORDSHIRE % I SampleEDITEDCounty BY Studies VOL. IV. 1883. LONDON: HARRISON AND SONS. ST. MARTIN’S LA NR. Staffordshire GENERAL MEETING,. 1 5 th OCTOBER, 1883. At the General Meeting of the above Society held at the William Salt Library, Stafford, on the 15th October, 1883, the Lord Lieutenant of the County in the chair, the following report of the Editorial Committee was read to the Meeting by the Honorary Secretary, and wasSample ordered to be printed, together with the Balance Sheet for 1882, in the AppendixCounty to the next volume. The Editorial Committee have to report that the third volume of Collections for a History of Staffordshire was issued to the subscribers in the early part of this year. The printing of Volume IV . is about half completed, and it is expected the volume will be in the hands of the subscribers early in the ensuing year. Its contents consist of tlio Plea Hells temp. Henry III., the Pinal Concords for the Studiessame reign, the "Warwickshire Pinal Concords affecting Staffordshire tenants from the earliest period up to the end of the reign of Henry 1I I .; and an abstract of the contents of the Ranfcon Chartu- lary. These comprise Part I. of the volume, which has been edited by the Honorary Secretary. Part II. of the volume will contain the History of Church Eaton and its members, by the Hon. and Rev. Canon Bridgeman. In pursuance of a resolution passed at the last General Meeting, the President of the Society wrote to the Marquis of Anglesey, forwarding a copy of the resolution in question, and requesting his Lordship’s favourable consideration of tbo proposal contained in it, to the effect that the Burton Chari ulary might he lodged for a stated period in the William Salt Library , for the purpose of making an abstract IV of its contents, to be printed subsequently by the Society. -

Proc. BSBI 1, 418-460

J!ER~UNALIA AND NOTICES TO MEMBEW; 417 'l'RE SOOIETY FOB VISI1'ING SOIENTISTS 'rhe Society for Visiting Scientists, Ltd., 5 Old Burlington Street, London, W.1, established in the spring of 1944 when Britain had the honour Qof welcQoming many scientists from Allied countries, seeks to be a focus for all scientists visiting the United Kingdom, and to put them in touch with British scientists and with one another. The Society aims to provide and encourage an active exchange of scientific thought and discussion between scientists of the United Kingdom and scientists from overseas. The House of the Society pro,vides a meeting place, a refectory, a ba.r and some residential acco=odation. In addition an information service is provided which is o'pen to. all visiting scientists, so that any scientist arriving in this country can, if he wishes, proceed at once to the House and be given such advice and information as is available. Among the Society's activities is the holding of receptions in honour of groups 00£ scientists visiting Britain, who thus have an o,pportunity of meeting at the House their British and oversea colleagues. Informal discussion meetings of general interest to scientists are Q.rganised. The Society provides a forum for topics which are outside the sOQope of specialised scientific societies but which are of importance to scientists as a whole. The Society's Officers are Professor A. V. Hill, C.H., O.B.E., F.R.S. (President and Chairman); Professor F. J. M. Stratton, D.8.0., O.B.E., F .R.S., and Mr. -

Public Record Office, London Lists and Indexes, Ijo. Ieiiiii. Iiiiieik of In

PU BLIC RECORD OFFICE, LON DON AN D I N D E X E L I S T S S , IJO . IEII I I I . I II I i E IK OF IN U I S I T I ON S PRES ERVED IN T HE P U BL IC RECORD OF F ICE . VT HA L E RY V III . T O P H I L IP M ARY H N . BY ARRAN GEM EN T W IT H H ER M AJES T Y’S S T AT ON ER Y I OF F ICE, L ON D ON ’ JEEW IQMRK } K R AU S R E P R I N T C O R P O R AT I O N 1 9 6 3 Calligraphic Amendments incorp orated from the master copy l n the S earch Room of the P ublic Record Office T h is s e ries was fi rs t pub lis he d o n b e h a lf o f t h e P u blic ’ R e c o rd O ffi c e b y H e r B rit a nn ic M a j es t y s S t a tio ne ry O ffic e a s fo ll o ws : Vo l s 1—3 8 b etwee n 18 92 a n d 19 12 ; — V o l 39 : 19 13 ; Vo ls 40 43 : 19 14 ; V o l 44 : 19 15 ; V o l 45 : 19 17 ; Vo ls 46— 48 : 1922 ; V o l 49 : 1923 ; V o l 50 : 192 7 ; Vo ls 5 1—52 : 1929 ; V o l 53 : 193 1 ; V o l 54 : 1933 ; V o l 55 1 6 R e int e b e rm is s io n a n d wit th e a th o rit 93 . -

Descendants of Hughes I De Cavalcamp Seigneur De Conches

Descendants of Hughes I de Cavalcamp Seigneur de Conches Generation 1 1 1. HUGHES IDE CAVALCAMP SEIGNEUR DE CONCHES was born about 890 AD. He died about 980 AD in pr. Conches, Eure, Evreux, Normandy, France. Notes for Hughes I de Cavalcamp Seigneur de Conches: The best source for descendants of "Hughes de Cavalcamp" in Normandy and England, with detailed charts and copious notes is, "Famille & seigneurs de Tosny" by Etienne Pattou (2012) found at: http://racineshistoire.free.fr/LGN/PDF/Tosny.pdf In speaking of Hugh of Calvacamp, Guillaume of Jumièges names [his great-grandson] “Rogerius Toenites de stirpe Malahulcii qui Rollonis ducis patruus fuera. Oderic Vitalis, writing in 1113, says the same thing (see entry for Malahule), and appears correct in that Rollo is the son of Ragnavald Eysteinsson the reported brother of Malahulc Eysteinsson. If this source is correct, then Hugh de Calvacamp would be the first cousin of Rollo. Wiki provides a perspective which downplays Orderic Vitalis: "The house Tosny (in England also Töny, Tonei, Toni and Tony) was a family of the Norman nobility, without actually coming from Normandy. They played on 10 to 12 Century the duchy a prominent role, without ever being honored with a Count or Viscount title. The Normandy in the second half of the 11th Century with the most important strongholds of Tosny The Tosny come with security from the Ile-de-France, although the top 12 of Orderic Vitalis Century reported that the family came from Malahulce. Progenitor is Hugo de Calvacamp. 942 his son Hugo, a monk at the Abbey of Saint-Denis, to the Archbishop of Reims was appointed, probably in his wake, the family had then settled in Normandy. -

List of Past Mayors

Mayors 1605 Michael Ireland 1606 Edmund Gravenor 1607 Clement Manesty 1608 John Finch 1609 Edward Carde 1610 John Sherley 1611 Michael Ireland 1612 John Vincent 1613 Robert Dawson 1614 John Finch 1615 Robert Goodman 1616 John Roberts 1617 Edmund Gravenor 1618 Edward Carde 1619 Edward Carde 1620 David Bromhal 1621 Thomas Thorogood 1622 Robert Dawson 1623 Christopher Browne 1624 Edward Lawrence 1625 Thomas Wright 1626 John Finch 1627 John Roberts 1628 Robert Dawson 1629 Edward Lawrence 1630 John Roberts 1631 John Dyer 1632 Christopher Browne 1633 George Hoppy 1634 Robert Dawson 1635 Gabriel Barbor 1636 Joseph Dalton 1637 Edward Lawrence 1638 John Dyer 1639 John Roberts 1640 George Hoppy 1641 Andrew Palmer 1642 Joseph Dalton 1643 Joseph Dalton 1644 Joseph Dalton 1645 Edward Lawrence 1646 William Turnour 1647 Isaac Puller 1648 William Gardiner 1649 John Clarke 1650 George Pettyt 1651 Joseph Bunker 1652 George Hoppy 1653 William Turnour 1654 John Roberts 1655 Joseph Dalton 1656 William Gardiner Edward Lawrence at death of William Gardiner 1657 Edward Lawrence 1658 William Turnour 1659 John Clarke 1660 Joseph Browne 1661 George Pettyt 1662 William Minors 1663 John Prichard 1664 George Seeley 1665 William Edmunds 1666 Edward Lawrence 1667 Benjamin Jones 1668 Samuel Goodman 1669 Thomas Pratt 1670 John Clarke 1671 John Prichard 1672 Edmund Bache 1673 William Edmunds 1674 Edward Lawrence 1675 John Dimsdale 1676 John Trott 1677 Benjamin Jones 1678 Israel Keynton 1679 William Stanes Edward Lawrence on death of William Stanes 1680 Edward Lawrence -

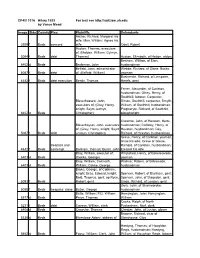

Sorted by County, Then Plaintiff

CP40/ 1076 Hilary 1533 For text see http://aalt.law.uh.edu by Vance Mead Image Side County Plea Plaintiffs Defendants Archer, Richard; Margaret his wife; Man, William; Agnes his 3929 f Beds concord wife Odell, Robert Aucton, Thomas, executors of; (Malden, William; Gylmyn, 5094 f Beds debt Thomas) Aucton, Elizabeth, of Hotton, widow Becham, William, of Eton, 6402 d Beds Barleman, John husbandman Belfeld, Joan, administrator Webbe, Richard, of Stone, Bucks, 5087 f Beds debt of; (Belfeld, William) yeoman Baskervile, Richard, of Lempster, 4482 f Beds debt execution Bently, Thomas Herefs, gent Ferrer, Alexander, of Carleton, husbandman; Olney, Henry, of Southhill, laborer; Carpenter, Bleverhassett, John, Simon, Southhill, carpenter; Smyth, executors of; (Grey, Henry, William, of Southhill, husbandman; knight; Seynt Jermyn, Ploghwryte, Richard, of Southhill, 6402 d Beds Christopher) ploughwright Crowche, John, of Hexston, Herts, Bleverhayset, John, executors husbandman; Coffeley, Henry, of of; (Grey, Henry, knight; Seynt Hexston, husbandman; Dey, 5087 f Beds debt Jermyn, Christopher) Richard, of Hexston, husbandman Greve, Henry, of Carleton, yeoman; Anne his wife; Greve or Grene, trespass and Richard, of Carleton, husbandman; 4632 f Beds contempt Bonham, thomas; Burell, John Eleanor his wife Bray, William, executor of; Whytehed, Henry, of Bekeleswade, 6403 d Beds (Cokke, George) yeoman Bray, William; Colmorth, Wolmar, Robert, of Beleswade, 6403 d Beds William; Cokke, George husbandman Broke, George, of Cobham, knight; Bray, Edward, knight; Spencer, -

Protections 395

PART II: PROTECTIONS 395 1295 1296 2092 December 13 2103 March 2 Contd. Robert de Brus, earl of Carrick [no. 1120], and Bello Campo, both with the king. [Both 24 June.] William de Rothyng, William de Brus, William de [ibid]. Badewe, Thomas de Reved, Nicholas de Barrington, Edmund de Badewe, Archibald le Bretun, Mr Andrew 2104 March 3 de Sancto Albano, Walter Crisp, all with him; John de Segrave with the king, and Richard de Theobald de Neyvill, Philip de Geyton, Easter. [C 67/11, m. 6]. Cornubia, Reginald de Hampden, Robert de Denemed and 1296 Richard le Venur de Laverton, all with John. 2093 January 10 [C 67/11, m. 6]. Walter de Agmondesham with the John de Monteforti, William Fauvel, Thomas de king; Robert de Mar. (C 67/11, m. 3]. Thomas de Shesnecote, Henry Dulee, John Dod, Richard de Lathum, Robert de Lathum [no. 1144], Adam de de Arcy, Whitacre. [All Easter.] [ibid]. Everyngeham, Philip de Arcy, Hugh John Brun, William de Berney, John Avenel, all with the 2094 January 17 bishop of Durham; Gregory de Broune, Hugh Wake Oliver la Zuche; 24 June. [ibid]. of Deping, both with John Wake; Giles de Brewose [no. 1124], Robert de Percy, William de Houk, 2095 January 18 Thomas de Stanlow, John Fayrfax, Roger de Roger le Bygod, earl of Norfolk and marshal of Goldstow, Godfrey de Melsa, all with the bishop England, John Lovel of Tychemersh. [Both 24 of Durham; John Pecche with William de Bello June.] [ibid]. Campo; Reginald de Cobeham with the earl of the 2096 January 19 Norfolk; John de Warenna, earl of Surrey, with Robert de Scales, Edward Charles. -

Kent Hundred Rolls Local Government and Corruption in The

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society THE KENT HUNDRED ROLLS: LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND CORRUPTION IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY JENNIFER WARD The Kent Hundred Rolls of 1274-5, preserved in the National Archives, provide a mine of information for local historians. Many were printed by the Record Commission in the early Mneteenth century, but the two bulky volumes are only to be found in major libraries and the rolls are printed in abbreviated Latin.1 The new edition by the Kent Archaeological Society [published on its website, www.kentarchaeology.ac] comprises the com- plete rolls for Kent, in the original Latin and in an English translation (by Dr Bridgett Jones), and makes the source much more widely accessible. The Kent Rolls are remarkably complete, although there are a few omissions. The major liberties are only mentioned incidentally, namely the lowy of Tonbridge and the hundred of Wachlingstone. in the hands of Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester and Hertford; Wye, in the hands of the abbot of Battle abbey, Sussex; and the Cinque Ports which had their own privileges. In addition, there is no return for Sheppey or Ospringe. The Hundred Rolls have been discussed by a number of legal and administrative Mstorians, notably by Helen Cam, whose The Hundred and the Hundred Rolls, published in 1930, is still of value today.2 Edward I returned from crusade in 1274 to a kingdom where the Crown had been weakened by civil war during the baroMal reform period of 1258-65, and where there was extensive local government corruption.