Climate Change Adaptation: Management Mangrove Forests, Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Township Map - Rakhine State 92° E 93° E 94° E Tilin 95° E Township Myaing Yesagyo Pauk Township Township Bhutan Bangladesh Kyaukhtu !( Matupi Mindat Mindat Township India China Township Pakokku Paletwa Bangladesh Pakokku Taungtha Samee Ü Township Township !( Pauk Township Vietnam Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Nyaung-U !( Paletwa Saw Township Saw Township Ngathayouk !( Bagan Laos Maungdaw !( Buthidaung Seikphyu Township CHIN Township Township Nyaung-U Township Kanpetlet 21° N 21° Township MANDALAYThailand N 21° Kyauktaw Seikphyu Chauk Township Buthidaung Kyauktaw KyaukpadaungCambodia Maungdaw Chauk Township Kyaukpadaung Salin Township Mrauk-U Township Township Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Ponnagyun Township Township Minbya Rathedaung Sidoktaya Township Township Yenangyaung Yenangyaung Sidoktaya Township Minbya Pwintbyu Pwintbyu Ponnagyun Township Pauktaw MAGWAY Township Saku Sittwe !( Pauktaw Township Minbu Sittwe Magway Magway .! .! Township Ngape Myebon Myebon Township Minbu Township 20° N 20° Minhla N 20° Ngape Township Ann Township Ann Minhla RAKHINE Township Sinbaungwe Township Kyaukpyu Mindon Township Thayet Township Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Mindon Township !( Bay of Bengal Ramree Kamma Township Kamma Ramree Toungup Township Township 19° N 19° N 19° Munaung Toungup Munaung Township BAGO Padaung Township Thandwe Thandwe Township Kyangin Township Myanaung Township Kyeintali !( 18° N 18° N 18° Legend ^(!_ Capital Ingapu .! State Capital Township Main Town Map ID : MIMU1264v02 Gwa !( Other Town Completion Date : 2 November 2016.A1 Township Projection/Datum : Geographic/WGS84 Major Road Data Sources :MIMU Base Map : MIMU Lemyethna Secondary Road Gwa Township Boundaries : MIMU/WFP Railroad Place Name : Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) translated by MIMU AYEYARWADY Coast Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Township Boundary www.themimu.info Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Yegyi Ngathaingchaung !( State/Region Boundary 2016. -

Download Report

Emergency Market Mapping and Analysis (EMMA) Understanding the Fish Market System in Kyauk Phyu Township Rakhine State. Annex to the Final report to DfID Post Giri livelihoods recovery, Kyaukphyu Township, Rakhine State February 14 th 2011 – November 13 th 2011 August 2011 1 Background: Rakhine has a total population of 2,947,859, with an average household size of 6 people, (5.2 national average). The total number of households is 502,481 and the total number of dwelling units is 468,000. 1 On 22 October 2010, Cyclone Giri made landfall on the western coast of Rakhine State, Myanmar. The category four cyclonic storm caused severe damage to houses, infrastructure, standing crops and fisheries. The majority of the 260,000 people affected were left with few means to secure an income. Even prior to the cyclone, Rakhine State (RS) had some of the worst poverty and social indicators in the country. Children's survival and well-being ranked amongst the worst of all State and Divisions in terms of malnutrition, with prevalence rates of chronic malnutrition of 39 per cent and Global Acute Malnutrition of 9 per cent, according to 2003 MICS. 2 The State remains one of the least developed parts of Myanmar, suffering from a number of chronic challenges including high population density, malnutrition, low income poverty and weak infrastructure. The national poverty index ranks Rakhine 13 out of 17 states, with an overall food poverty headcount of 12%. The overall poverty headcount is 38%, in comparison the national average of poverty headcount of 32% and food poverty headcount of 10%. -

Rakhine State Census Report Volume 3 – K

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State Census Report Volume 3 – K Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State Report Census Report Volume 3 – K For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014, and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is now my hope that the main results, both Union and each of the State and Region reports, will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national and sub-national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and officers at the State/Region, District and Township Levels, and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. The technical support and our strong desire to follow international standards affirmed our commitment to strict adherence to the guidelines and recommendations, which form part of international best practices for census taking. -

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations. Morten Bergsmo; Wolfgang Kaleck; Kyaw Yin Hlaing. Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, 40, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, pp.177-227, 2020, Publication Series, 978-82-8348-134-1. hal- 02997366 HAL Id: hal-02997366 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02997366 Submitted on 10 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors) E-Offprint: Jacques P. Leider, “The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations”, in Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors), Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPub- lisher, Brussels, 2020 (ISBNs: 978-82-8348-133-4 (print) and 978-82-8348-134-1 (e- book)). This publication was first published on 9 November 2020. TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site https://www.toaep.org which uses Persistent URLs (PURLs) for all publications it makes available. -

Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma

To: Hon. Mr. Ban Ki-moon Secretary-General United Nations From: Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma CC: Mr. B. Lynn Pascoe, Under-Secretary-General, United Nations Mr. Ibrahim Gambari, Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser to the Secretary- General on Myanmar/Burma Permanent Representatives to the United Nations of the five Permanent Members (China, Russia, France, United Kingdom and the United states) of the UN Security Council U Aung Shwe, Chairman, National League for Democracy Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, General Secretary, National League for Democracy U Aye Thar Aung, Secretary, Committee Representing the Peoples' Parliament (CRPP) Veteran Politicians The 88 Generation Students Date: 1 August 2007 Re: National Reconciliation and Democratization in Myanmar/Burma Dear Excellency, We note that you have issued a statement on 18 July 2007, in which you urged the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) (the ruling military government of Myanmar/Burma) to "seize this opportunity to ensure that this and subsequent steps in Myanmar's political roadmap are as inclusive, participatory and transparent as possible, with a view to allowing all the relevant parties to Myanmar's national reconciliation process to fully contribute to defining their country's future."1 We thank you for your strong and personal involvement in Myanmar/Burma and we expect that your good offices mandate to facilitating national reconciliation in Myanmar/Burma would be successful. We, Members of Parliament elected by the people of Myanmar/Burma in the 1990 general elections, also would like to assure you that we will fully cooperate with your good offices and the United Nations in our effort to solve problems in Myanmar/Burma peacefully through a meaningful, inclusive and transparent dialogue. -

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State”

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State” Table of Contents KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 5 1.1. POLITICAL PARTY LANDSCAPE IN RAKHINE STATE............................................................................ 7 1.2. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON FREE AND FAIR ELECTIONS .............................................................. 8 1.3. ELECTORAL SYSTEM IN MYANMAR ................................................................................................. 10 2. OBJECTIVE AND SCOPE OF THE STUDY ..................................................................................... 11 1. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 11 1.1. SAMPLING ...................................................................................................................................... 11 1.2. RESEARCH PROCESS ........................................................................................................................ 12 1.3. LIMITATION OF STUDY .................................................................................................................... 12 2. FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................ -

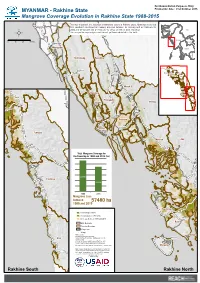

Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015

For Humanitarian Purposes Only MYANMAR - Rakhine State Production date : 21st October 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015 This map illustrates the evolution of mangrove extent in Rakhine State, Myanmar as derived Bhutan from Landsat-5 multispectral imagery acquired between 13 January and 23 February for Nepal Mindat 1988 and 30 January and 24 February for 2015 at 30m of pixel resolution. India China Town Bangladesh Bangladesh This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Paletwa Town Viet Nam Myanmar 0 10 20 30 Kms Laos Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Town Town Maungdaw Thailand Buthidaung Kyauktaw Cambodia Taungpyoletwea Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Town Buthidaung Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Mrauk-U Town Maungdaw Rathedaung Mrauk-U Ponnagyun Town Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Pauktaw Minbya Sittwe Pauktaw Myebon Sittwe Myebon Ann Ann Mrauk-U Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Rathedaung Mrauk-U Munaung Munaung Toungup Town Ann Thandwe Ponnagyun Thandwe Rathedaung Minbya Kyeintali Mindon Ma-Ei Town Town Town Gwa Gwa Ramree Minbya Town Ponnagyun Town Pauktaw Sittwe Pauktaw Town Sittwe Toungup Town Myebon Town Myebon Ann Toungup Town Total Mangrove Coverage for the Township in 1988 and 2015 (ha) Ann Town Thandwe Town 280986 Thandwe 223506 Kyaukpyu 1988 2015 Town Mangrove Loss between 57480 ha 1988 and 2015 Kyaukpyu New Mangrove area Kyeintali Town Remaining area 1988-2015 Ramree Decrease between 1988 and 2015 Town Ramree State Boundary Township Boundary Village-Tract Village Data sources: Toungup Landcover Analysis: UNOSAT Administrative Boundaries, Settlements: OCHA Munaung Gwa Town Roads: OSM Coordinate System: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N Contact: [email protected] File: REACH_MMR_Map_Rakhine_HVA_Mangrove_21OCT2015_A1 Munaung Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Gwa Town on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, associated, donors mentioned on this map. -

Zootaxa, Danio Aesculapii, a New Species of Danio

Zootaxa 2164: 41–48 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Danio aesculapii, a new species of danio from south-western Myanmar (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) SVEN O. KULLANDER & FANG FANG Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Danio aesculapii, new species, is described from small rivers on the western slope of the Rakhine Yoma in south-western Myanmar. It is superficially similar to D. choprae from northern Myanmar in having a series of vertical bars anteriorly on the side, but differs from it and other species of Danio in having six instead of seven or more branched dorsal-fin rays, and from all other species of Danio except D. erythromicron and D. kerri in having 12 instead of 10 or 14 circumpeduncular scale rows. Key words: Rakhine Yoma, Thandwe, Danio choprae, endemism Introduction The cyprinid fish genus Danio Hamilton includes 14 small species in South and Southeast Asia (Kullander et al. 2009), as a rule diagnosable by distinct species-specific colour patterns. About half of the species of Danio have a pigment pattern that consists of one or more dark or light horizontal stripes (Fang, 1998). Among the others, Danio kyathit Fang differs in having the stripes broken up into rows of small brown spots, D. margaritatus (Roberts) has a pattern of small light spots on the sides, D. dangila (Hamilton) has rows of dark rings with light centres, and D. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State

ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 1/2 RH PT Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State (Source: Myanmar Information Management Unit) http://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/State_Map_D istrict_Rakhine_MIMU764v04_23Oct2017_A4.pdf ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 2/2 RH PT Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Rakhine State 92° EBANGLADESH 93° E 94° E 95° E Pauk !( Kyaukhtu INDIA Mindat Pakokku Paletwa CHINA Maungdaw !( Samee Ü Taungpyoletwea Nyaung-U !( Kanpetlet Ngathayouk CHIN STATE Saw Bagan !( Buthidaung !( Maungdaw District 21° N THAILAND 21° N SeikphyuChauk Buthidaung Kyauktaw Kyauktaw Kyaukpadaung Maungdaw Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Mrauk-U Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Mrauk-U District Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Minbya Pwintbyu Sittwe DistrictPonnagyun Pauktaw Sittwe Saku !( Minbu Pauktaw .! Ngape .! Sittwe Myebon Ann Magway Myebon 20° N RAKHINE STATE Minhla 20° N Ann MAGWAY REGION Sinbaungwe Kyaukpyu District Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu !( Mindon Ramree Toungup Ramree Kamma 19° N 19° N Bay of Bengal Munaung Toungup Munaung Padaung Thandwe District BAGO REGION Thandwe Thandwe Kyangin Legend .! State/Region Capital Main Town !( Other Town Kyeintali !( 18° N Coast Line 18° N Map ID: MIMU764v04 Township Boundary Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 State/Region Boundary Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 International Boundary Data Sources: MIMU Gwa Base Map: MIMU Road Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Kyaukpyu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) Gwa translated by MIMU Maungdaw Mrauk-U Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Sittwe Ngathaingchaung Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Kilometers !( Thandwe 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 15 30 60 Yegyi 92° E 93° E 94° E 95° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Where There Is Police, There Is Persecution Government Security

Physicians for Where There is Police, Human Rights There is Persecution Government Security Forces and October 2016 Human Rights Abuses in Myanmar’s Northern Rakhine State An immigration officer inspects Rohingyas’ paperwork at a checkpoint in Rakhine State. About Physicians for Human Rights For 30 years, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has used science and medicine to document and call attention to mass atrocities and severe human rights violations. PHR is a global organization founded on the idea that health professionals, with their specialized skills, ethical duties, and credible voices, are uniquely positioned to stop human rights violations. PHR’s investigations and expertise are used to advocate for persecuted health workers and medical facilities under attack, prevent torture, document mass atrocities, and hold those who violate human rights accountable. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Introduction This report was written by Claudia Rader edited and Widney Brown, Physicians for prepared the report for 4 Methodology Human Rights (PHR) program publication. director, and is based on field 6 Background research conducted from November PHR would like to acknowledge 2015 to May 2016 in Myanmar the Bangladesh-based research 8 Findings (Rakhine State and Yangon) and team who contributed to the Bangladesh. study, design, and data collection 20 Discussion and also reviewed and edited the The report benefited from review report. PHR would also like to 24 Conclusion and by PHR leadership and staff, thank other external reviewers Recommendations including DeDe Dunevant, director who wish to remain anonymous. of communications, Donna McKay, 27 Endnotes MS, executive director, Marianne PHR is deeply indebted to the Møllmann, LLM, MSc, senior Rohingya and Rakhine people researcher, and Claudia Rader, MS, who were willing to share their content and marketing manager.