American Idol: Should It Be a Singing Contest Or a Popularity Contest?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Idole Americaine Est Gay Kris Allen

Idole Americaine Est Gay Kris Allen 1 / 3 Idole Americaine Est Gay Kris Allen 2 / 3 Kris Allen is the new American Idol after knocking off Adam Lambert ... a singing and fashion style reminiscent of gay icons from Queen singer .... "American Idol" runner-up Adam Lambert tells Rolling Stone Magazine that he's gay. (June 9). whoa-- u sing like that guy who won american idol... uh oh yah Kris Allen. ... His win was a shock to most but his hometown Arkansas is known for backing their people MAJOR whatever it takes. He has that ... Dude 2: "The gay guy from Idol.". Kris Allen, a married former Christian missionary from Conway, Ark., went up ... We do not actually know whether Adam is gay -- he hasn't said so -- but it was .... Jump to American Idol - Fox and AT&T have stated that they "stand by the outcome" and are "absolutely certain" that "Kris Allen is the American Idol".. However, there does seem to be a distinction made in which blackness is a recognizable ... More than Lambert appearing on American Idol as the first “out” gay ... by the final two white male contestants, Lambert and eventual winner Kris Allen, .... Music, Media, and Identity in American Idol Katherine Meizel ... featuring as protagonists the Top 2 Season 8 finalists, Kris Allen and Adam Lambert. ... in Idol housing during the season; while Lambert was widely assumed to be gay but never ... of what is known as popslash, a genre that has primarily, though not exclusively, .... Who else is speaking up for traditional marriage, besides right-wing pundits and .. -

Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Kicks Off Annual Eight-Day

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: March 4, 2015 Oname Thompson (703) 864-5980 cell [email protected] Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Kicks Off Annual Eight-Day, Seven- Country USO Spring Troop Visit and Brings Warmth to Troops Early Chuck Pagano, Andrew Luck, Dwayne Allen, David DeCastro, Diana DeGarmo, Ace Young, Dennis Haysbert, Miss America 2015 Kira Kazantsev, Phillip Phillips and Wee Man join Admiral James Winnefeld in Extending America’s Thanks ARLINGTON, VA (Mar. 4, 2015) – Nothing marks the end of a blistering, cold winter quite like the annual USO Spring Troop Visit led by the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral James A. Winnefeld, Jr. The eight-day, seven country USO tour is designed to appeal to troops of all ages and bring a much needed touch of home to those serving abroad. This year’s variety-style USO tour is a fusion of music, comedy and heartfelt messages of support featuring Indianapolis Colts head coach Chuck Pagano, quarterback Andrew Luck and tight end Dwayne Allen; Pittsburgh Steelers guard David DeCastro; “American Idol” alumni Diana DeGarmo and Ace Young; American film, stage and television actor Dennis Haysbert; Miss America 2015 Kira Kazantsev; platinum recording artist and season 11 “American Idol” winner Phillip Phillips; as well as motion picture and television personality Jason “Wee Man” Acuna. ***USO photo link below with images added daily*** DETAILS: The tour will visit various countries in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia Pacific, as well as an aircraft carrier at sea. Three days into the moment-filled USO tour, the group has visited two military bases and created #USOMoments for more than 1,300 troops and military families. -

American Idol Synthesis

English Language and Composition Reading Time: 15 minutes Suggested Writing Time: 40 minutes Directions: The following prompt is based on the accompanying four sources. This question requires you to integrate a variety of sources into a coherent, well-written essay. Refer to the sources to support your position: avoid mere paraphrase or summary. Your argument should be central; the sources should support this argument. Remember to attribute both direct and indirect citations. Introduction In a culture of television in which the sensations of one season must be “topped” in the next, where do we draw the line between decency and entertainment? In the sixth season of popular TV show, “American Idol”, many Americans felt that the inclusion of mentally disabled contestants was inappropriate and that the remarks made to these contestants were both cruel and distasteful. Did this television show allow mentally disabled contestants in order to exploit them for entertainment? Assignment Read the following sources (including any introductory information) carefully. Then, in an essay that synthesizes the sources for support, take a position that defends, challenges, or qualifies the claim that the treatment of mentally disabled reality TV show contestant, Jonathan Jayne, was exploitative. Refer to the sources as Source A, Source B, etc.: titles are included for your convenience. Source A (Americans with Disabilities Act) Source B (Kelleher) Source C (Goldstein) Source D (Special Olympics) **Question composed and sources compiled by AP English Language and Composition teacher Wendy Turner, Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, Lexington, KY, on February 7, 2007. Source A The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. -

KANG-THESIS.Pdf (614.4Kb)

Copyright by Jennifer Minsoo Kang 2012 The Thesis Committee for Jennifer Minsoo Kang Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar Karin G. Wilkins From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 by Jennifer Minsoo Kang, B.A.; M.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication To my family; my parents, sister and brother Abstract From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 Jennifer Minsoo Kang, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar The format program trade has grown rapidly in the past decade and has become an important part of the global television market. This study aimed to give an understanding of this phenomenon by examining how global formats enter and become incorporated into the national media market through a case study analysis on the Korean format market. Analyses were done to see how the historical background influenced the imported format flows, how the format flows changed after the media liberalization period, and how the format uses changed from illegal copying to partial formats to whole licensed formats. Overall, the results of this study suggest that the global format program flows are different from the whole ‘canned’ program flows because of the adaptation processes, which is a form of hybridity, the formats go through. -

Reality Television Participants As Limited-Purpose Public Figures

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 6 Issue 1 Issue 1 - Fall 2003 Article 4 2003 Almost Famous: Reality Television Participants as Limited- Purpose Public Figures Darby Green Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Privacy Law Commons Recommended Citation Darby Green, Almost Famous: Reality Television Participants as Limited-Purpose Public Figures, 6 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 94 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol6/iss1/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. All is ephemeral - fame and the famous as well. betrothal of complete strangers.' The Surreal Life, Celebrity - Marcus Aurelius (A.D 12 1-180), Meditations IV Mole, and I'm a Celebrity: Get Me Out of Here! feature B-list celebrities in reality television situations. Are You Hot places In the future everyone will be world-famous for fifteen half-naked twenty-somethings in the limelight, where their minutes. egos are validated or vilified by celebrity judges.' Temptation -Andy Warhol (A.D. 1928-1987) Island and Paradise Hotel place half-naked twenty-somethings in a tropical setting, where their amorous affairs are tracked.' TheAnna Nicole Show, the now-defunct The Real Roseanne In the highly lauded 2003 Golden Globe® and Show, and The Osbournes showcase the daily lives of Academy Award® winner for best motion-picture, Chicago foulmouthed celebrities and their families and friends. -

Idol Season 9: Top 4 -- Crystal Back in Action

BIG NEWS: Celebrity Skin | Jersey Shore | Ellen Degeneres | Celebrity Body | Energy Debates | More... LOG IN | SIGN UP JANUARY 7, 2011 FRONT PAGE POLITICS BUSINESS MEDIA ENTERTAINMENT COMEDY SPORTS STYLE WORLD GREEN FOOD TRAVEL TECH LIVING HEALTH DIVORCE ARTS BOOKS RELIGION IMPACT EDUCATION COLLEGE NY LA CHICAGO DENVER BLOGS Michael Giltz BIO Get Email Alerts Freelance writer and raconteur Become a Fan Bloggers' Index MOST POPULAR ON HUFFPOST Posted: May 12, 2010 09:23 AM More Dead Birds, Fish Idol Season 9: Top 4 -- Crystal Back Found Across The World in Action Recommend 65K Camille Grammer's Porn What's Your Reaction: Past Comes Back To Haunt Inspiring Funny Hot Scary Outrageous Amazing Weird Crazy Her Read More: Casey James , Crystal Bowersox , Ellen Degeneres , Kara DioGuardi , Lee Dewyze , Michael Like 689 Lynche , Movies , Pop Music , Randy Jackson , Reality TV , Ryan Seacrest , Simon Cowell , Entertainment News Elizabeth Edwards' Will It was movie night on American Idol and Crystal Revealed SHARE THIS STORY Bowersox appeared in her own production of A Star Is Recommend 533 (Re)Born. After a few weeks of showing "another side" to herself (sides that weren't that gripping), she got Intestinal Parasites May Be 0 back down to business with a bluesy spin on the 0 views 0 6 Causing Your Energy Kenny Loggins tune "I'm Alright" and a great duet Slump with Lee Dewyze on "Falling Slowly" from the indie Like 521 film Once. Any questions as to whether she would Get Entertainment Alerts make it to the winner's circle are over. Vegas, stop the Rudeness Is A Neurotoxin betting; Crystal will win it. -

Rca Records to Release American Idol: Greatest Moments on October 1

THE RCA RECORDS LABEL ___________________________________________ RCA RECORDS TO RELEASE AMERICAN IDOL: GREATEST MOMENTS ON OCTOBER 1 On the heels of crowning Kelly Clarkson as America's newest pop superstar, RCA Records is proud to announce the release of American Idol: Greatest Moments on Oct. 1. The first full-length album of material from Fox's smash summer television hit, "American Idol," will include four songs by Clarkson, two by runner-up Justin Guarini, a song each by the remaining eight finalists, and “California Dreamin’” performed by all ten. All 14 tracks on American Idol: Greatest Moments, produced by Steve Lipson (Backstreet Boys, Annie Lennox), were performed on "American Idol" during the final weeks of the reality-based television barnburner. In addition to Kelly and Justin, the show's remaining eight finalists featured on the album include Nikki McKibbon, Tamyra Gray, EJay Day, RJ Helton, AJ Gil, Ryan Starr, Christina Christian, and Jim Verraros. Producer Steve Lipson, who put the compilation together in an unprecedented two-weeks time, finds a range of pop gems on the album. "I think Kelly's version of ‘Natural Woman' is really strong. Her vocals are brilliant. She sold me on the song completely. I like Christina's 'Ain't No Sunshine.' I think she got the emotion of it across well. Nikki is very good as well -- very underestimated. And Tamyra is brilliant too so there's not much more to say about her." RCA Records will follow American Idol: Greatest Moments with the debut album from “American Idol” champion Kelly Clarkson in the first quarter of 2003. -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

Words by ELIZABETH FORREST Photos by CATHERINE POWELL

MADDIE POPPEWords by ELIZABETH FORREST Photos by CATHERINE POWELL 06 Maddie Poppe, winner of show with her family and admired on the show, ‘how many people Season 16 of American Idol, the track record for its winners and are really watching?’” she explains. remembers exactly what she was contestants. That might intimi- It was hard for her to picture the thinking when Ryan Seacrest date some, but when it came to millions behind the screen. “But called her name during the season auditions, Maddie wasn’t afraid. “I after the show when we met people finale. “I had a flashback of every- didn’t think I had anything to lose. and looked out into the crowd, you thing that happened on the show,” I had been told ‘no’ so many times saw little girls with ponytails and she says. “I went from my audition, that I wasn’t really scared anymore. overalls. They were so excited to to the Hollywood week, to Top 50, I decided to just go for it,” she says. meet me and it’s crazy because I to Top 24. I kind of reflected on Being separated from her family still feel like I’m still such a regular, all the moments I never thought during the show was difficult. normal person,” Maddie laughs. I could do it, and it was unbeliev- Time with them was limited and Not only did Maddie win the able.” Music had always been a she was exposed to an entirely hearts of young girls; Katy Perry part of Maddie’s life, but she was new lifestyle far from her Midwest and Idina Menzel are fans of the no stranger to the word “no” going hometown. -

Kelly Clarkson American Idol 2004

Kelly clarkson american idol 2004 Since U Been Gone Live on The Christmas Special of American Idol: Kelly, Ruben & Fantasia: Home for. Kelly Clarkson performing Breakaway Live On the American Idol Christmas Special. Kelly Clarkson - Breakaway (Live American Idol Christmas Special) . This is my favourite song and. Kelly's emotions run as high as her vocals while performing her intimately personal song "Piece by Piece. Kelly Brianne Clarkson (born April 1, ) is an American pop-rock of her multi-platinum second album, Breakaway (), Clarkson moved to a more pop. 1 on two charts, Kelly Clarkson is the first American Idol contestant to earn reign on the Top Independent Albums chart on April 24, When American Idol premiered on Fox-TV on June 11, , it was far Then along came Kelly Clarkson, though the singer from Burleson, Texas, .. , "Idol" executive producers Nigel Lythgoe and Ken Warwick were. Kelly Clarkson performs on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno on August 9, in Burbank, California. Her second album, Breakaway, came. (CNN) Season 1 "American Idol" winner and breakout star Kelly Clarkson returned to the stage that made her famous Thursday night to mark. 'American Idol' is returning from the dead, but its top dawgs, Kelly Clarkson and Simon Cowell aren't coming along for the ride. Jennifer Hudson — who was on American Idol back in — will be a coach on Season 13 of. Kelly Brianne Clarkson was born in Fort Worth, Texas, to Jeanne Ann (Rose) She was the first winner of the series American Idol, in American Idol (TV Series) (performer - 20 episodes, - ) (writer - 4 episodes, - ). -

DAVID FOSTER: HITMAN TOUR FEATURING SPECIAL GUEST KATHARINE Mcphee ANNOUNCED in the 2019-2020 KAUFFMAN CENTER PRESENTS SERIES

NEWS RELEASE Contact: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Ellen McDonald, Publicist Monday, September 16, 2019 Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts (816) 213-4335 | [email protected] Bess Wallerstein Huff, Director of Marketing Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts (816) 994-7229 | [email protected] DAVID FOSTER: HITMAN TOUR FEATURING SPECIAL GUEST KATHARINE McPHEE ANNOUNCED IN THE 2019-2020 KAUFFMAN CENTER PRESENTS SERIES An Intimate Evening with David Foster: Hitman Tour Featuring Special Guest Katharine McPhee coming to Muriel Kauffman Theatre on May 19 Kansas City, MO – Today, the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts announced AN additional performance in the 2019- 2020 Kauffman Center Presents series. David Foster and Katharine McPhee will perform in Muriel Kauffman Theatre on Tuesday, May 19 at 7:30 p.m. GRAMMY Award-winning producer David Foster is embarking on an extensive North American tour beginning January of 2020 and ending at the Kauffman Center on May 19. The tour, An Intimate Evening with David Foster: Hitman Tour, is an extension of his highly successful and sold-out 2019 tour. Foster, who is one of the biggest musical forces of our time, created this jaw-dropping musical extravaganza that includes the greatest hits of his career. Thrilling, humorous and refreshingly honest, David Foster performs songs he wrote or produced from his four decades of hits and includes fascinating storytelling about the songs, artists, and moments of his life. Delivered by powerhouse performers, the hits include Celine Dion’s “Because You Loved Me,” Whitney Houston’s “The Bodyguard,” Earth Wind and Fire’s “After The Love Is Gone,” Chicago’s ”You’re The Inspiration,” Josh Groban’s “You Raise Me Up,” Michael Bublé’s “Home,” Natalie Cole’s “Unforgettable,” and many more. -

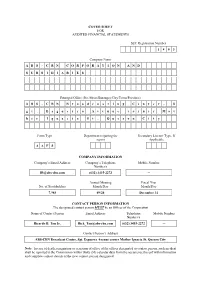

COVER SHEET for AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A

COVER SHEET FOR AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A B S - C B N C O R P O R A T I O N A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S Principal Office (No./Street/Barangay/City/Town/Province) A B S - C B N B r o a d c a s t i n g C e n t e r , S g t . E s g u e r r a A v e n u e c o r n e r M o t h e r I g n a c i a S t . Q u e z o n C i t y Form Type Department requiring the Secondary License Type, If report Applicable A A F S COMPANY INFORMATION Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Mobile Number Number/s [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Annual Meeting Fiscal Year No. of Stockholders Month/Day Month/Day 7,985 09/24 December 31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Mobile Number Number/s Ricardo B. Tan Jr. [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Contact Person’s Address ABS-CBN Broadcast Center, Sgt. Esguerra Avenue corner Mother Ignacia St. Quezon City Note: In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated.