Reality Show Contestants As a Distinct Category of Research Respondents Who Challenge and Blur Rigid Divisions Between Audience and Text, and Audience and Producer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Their Stories Tell Us: Research Findings from the Sisters In

What Their Stories Tell Us Research findings from the Sisters In Spirit initiative Sisters In Spirit 2010 Research Findings Aboriginal women and girls are strong and beautiful. They are our mothers, our daughters, our sisters, aunties, and grandmothers. Acknowledgments This research would not have been possible without the stories shared by families and communities of missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls. The Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) is indebted to the many families, communities, and friends who have lost a loved one. We are continually amazed by your strength, generosity and courage. We thank our Elders and acknowledge First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities for their strength and resilience. We acknowledge the dedication and commitment of community and grassroots researchers, advocates, and activists who have been instrumental in raising awareness about this issue. We also acknowledge the hard work of service providers and all those working towards ending violence against Aboriginal women in Canada. We appreciate the many community, provincial, national and Aboriginal organizations, and federal departments that supported this work, particularly Status of Women Canada. Finally, NWAC would like thank all those who worked on the Sisters In Spirit initiative over the past five years. These contributions have been invaluable and have helped shape the nature and findings of this report. This research report is dedicated to all Aboriginal women and girls who are missing or have been lost to violence. Sisters In Spirit 2010 Research Findings Native Women’s Association of Canada Incorporated in 1974, the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) is founded on the collective goal to enhance, promote, and foster the social, economic, cultural and political well- being of Aboriginal women within Aboriginal communities and Canadian society. -

Sounds of the Lobby Lounge

SOUNDS OF THE LOBBY LOUNGE Entertainment Schedule April - May 2020 Tune in every Wednesday from 4:15pm - 5:00pm (PST) via Facebook live for virtual music sessions highlighting some of Vancouver’s best talent that traditionally headline the stage at The Lobby Lounge, curated by Siegel Entertainment. APRIL Adam Thomas, 4:15pm (PST) 29 JUNO Nominated vocalist Adam Thomas performs favourite radio hits from this year all the way back to the jazz and big band era, and a wide array of classics from in between. His unique sound combines elements of soul, jazz, indie and top 40 music. MAY Antoinette Libelt, 4:15pm (PST) 6 Antoinette Libelt is an indie pop diamond in the rough. Growing up listening to artists like Michael Jackson and Aretha Franklin, she has emulated their powerful and soulful voices. Her style ranges from Top 40 hits to RnB and Country, ensuring her performance will have something for everyone. MAY Neal Ryan, 4:15pm (PST) 13 Originally from Dublin, Ireland and hailing from an intensely musical family, Neal Ryan’s love for his craft comes from a long lineage of storytellers, musicians and artists. Neal’s own original works bear large resemblance to the “Troubadour” era of the late 60’s and 70’, with inspiration from artists like James Taylor and Cat Stevens. MAY Rob Eller, 4:15pm (PST) 20 Rob Eller is a signer/guitarist/entertainer who chooses to express his music as a solo, and has had a guitar in his hands since his 9th birthday. He fills up the rooms he performs in with the sound of a full band, paying extra attention to musical dynamics, continually finding new ways to express a song. -

KANG-THESIS.Pdf (614.4Kb)

Copyright by Jennifer Minsoo Kang 2012 The Thesis Committee for Jennifer Minsoo Kang Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar Karin G. Wilkins From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 by Jennifer Minsoo Kang, B.A.; M.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication To my family; my parents, sister and brother Abstract From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 Jennifer Minsoo Kang, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar The format program trade has grown rapidly in the past decade and has become an important part of the global television market. This study aimed to give an understanding of this phenomenon by examining how global formats enter and become incorporated into the national media market through a case study analysis on the Korean format market. Analyses were done to see how the historical background influenced the imported format flows, how the format flows changed after the media liberalization period, and how the format uses changed from illegal copying to partial formats to whole licensed formats. Overall, the results of this study suggest that the global format program flows are different from the whole ‘canned’ program flows because of the adaptation processes, which is a form of hybridity, the formats go through. -

Teachers Depart Coos Bay for North Bend What's With

C M C M Y K Y K Coupons Sports Money State Go!&Outdoors Use our ads to Fall high school Charleston makes Newest spider Oregon Shorebird save big at your sports practices way for new family discovered festival swoops in favorite retailers start Monday Marine Life Center in Grants Pass next week TV LISTINGS D4 brought to you by Serving Oregon’s South Coast Since 1878 SATURDAY,AUGUST 18, 2012 theworldlink.com I $1.50 Farmers fear their hard work may be destroyed Years worth of work could be washed away upon approval of a proposal to flood the wetland BY DANIEL SIMMONS-RITCHIE garden property which has been this The World way since the ’70s.” Crawford is not alone. According to WINTER LAKE - Every resident Coos County commissioner Bob Main, learns to live with the flood. 37 residents have emailed him with Each year, with cruel seasonality, concerns about the proposal. this peat-land is transformed into a “They are upset,”Main said. “They 1,700-acre soup. are very upset, and I don’t blame But this year, emotions have them.” piqued over a different deluge. Spearheaders of the wetland project Next year, earthworks are slated to are battling to quell those fears. The begin on a $3.5 million project to group promises that channels and tide restore 400 acres of pasture to gates will protect surrounding wetland. landowners. Sarah Crawford, an organic farmer on Garden Valley Road, worries that SEE FLOODING | A10 new body of water will radically alter the valley’s water table. “That would ruin us,” Crawford said. -

ACRONYM 13 - Round 6 Written by Danny Vopava, Erik Nelson, Blake Andert, Rahul Rao-Potharaju, William Golden, and Auroni Gupta

ACRONYM 13 - Round 6 Written by Danny Vopava, Erik Nelson, Blake Andert, Rahul Rao-Potharaju, William Golden, and Auroni Gupta 1. This album was conceived after the master tapes to the album Cigarettes and Valentines were stolen. A letter reading "I got a rock and roll girlfriend" is described in a multi-part song at the end of this album. A teenager described in this albumis called the "son of rage and love" and can't fully remember a figure he only calls (*) "Whatsername." A "redneck agenda" is decried in the title song of this album, which inspired a musical centered onthe "Jesus of Suburbia." "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" appears on, for 10 points, what 2004 album by Green Day? ANSWER: American Idiot <Nelson> 2. In 1958, Donald Duck became the first non-human to appear in this TV role, which was originated by Douglas Fairbanks and William C. DeMille. James Franco appeared in drag while serving in this role, which went unfilled in 2019 after (*) Kevin Hart backed out. The most-retweeted tweet ever was initiated by a woman occupying this role, which was done nine other times by Billy Crystal. While holding this role in 2017, Jimmy Kimmel shouted "Warren, what did you do?!" upon the discovery of an envelope mix-up. For 10 points, name this role whose holder cracks jokes between film awards. ANSWER: hosting the Oscars [accept similar answers describing being the host of the Academy Awards; prompt on less specific answers like award show host or TV show host] <Nelson> 3. As of December 2019, players of this game can nowmake Dinosaur Mayonnaise thanks to its far-reaching 1.4 version update, nicknamed the "Everything Update." Every single NPC in this game hates being given the Mermaid's Pendant at the Festival of the Winter Star because it's only meant to be used for this game's (*) marriage proposals. -

Principals Involved in Lucid Plan Aren?T Done with Aurora

This page was exported from - The Auroran Export date: Thu Sep 30 6:36:34 2021 / +0000 GMT Principals involved in Lucid plan aren?t done with Aurora By Brock Weir With Aurora Live! dead in the water, enough time has passed for heads to cool and assess the situation. But George Roche, founder of Lucid Productions, the group that brought forward the Aurora Live! festival isn't completely done with Aurora. 2014, he said, is definitely a possibility. ?I would love to [bid on a festival] if we can get the ?Wild, Wild West' politics and the cynicism projected by [Councillor Chris Ballard] which I believe rises out of the treatment unto the Aurora Jazz Fest organizers,? said Mr. Roche, referring to the war of words between himself and the Councillor while the festival was still on the table. ?We always had a great feeling of working with Aurora and nothing has changed. When things go a little bit sideways obviously politicians start to protect themselves and their own credibility within the Town, but in this case the credibility wasn't protected.? Credibility also took a hit, he claims when Councillor Abel began to get ?demanding? on which bands should take to the stage and how much they should be paid, as well as what he describes as a ?spectacle? being made out of their references. ?2013 is out of the question [for a festival],? he said. ?We're very sorry it didn't go the way we had proposed. It wasn't anything to do with our actions, certainly being the lead writer and the pitchmen for the plan, I certainly wouldn't have done anything to hijack my own proposal. -

Mainstage Series Sponsor Performance Sponsors

THE Mainstage Series Sponsor Performance Sponsors MISSION STATEMENT Manitoba Opera is a non-profit arts organization dedicated to changing people’s lives through the glory of opera. MANITOBA OPERA OFFICE Lower Level, Centennial Concert Hall Room 1060, 555 Main Street Winnipeg, MB R3B 1C3 BOX OFFICE LARRY DESROCHERS General Director & CEO 9:30 am - 4:30 pm, Monday to Friday MANITOBANS Single Tickets: 204-944-8824 TADEUSZ BIERNACKI Subscriber Services Hotline: 204-957-7842 Assistant Music Director/Chorus Master BANd Online: tickets.mbopera.ca MICHAEL BLAIS Website: mbopera.ca Director of Administration To advertise in this program call: BETHANY BUNKO 204-944-8824 TOGETHER Communications Coordinator TANIA DOUGLAS Manitoba Opera is a member of the Being part of this community means we can count on Association for Opera in Canada Director of Development and Opera America. each other even in uncertain times. By joining us here JAYNE HAMMOND Grants & Corporate Giving Manager today, we unite in supporting local artists, musicians and SHELDON JOHNSON Director of Production performing arts groups, letting them know that they can LIZ MILLER Manitoba Opera gratefully acknowledges the Annual Giving Manager count on us, while at the same time, reminding encouragement and financial support given by the following: SCOTT MILLER Education & Community Engagement one another that we’re still all in this together. Coordinator TYRONE PATERSON Music Advisor & Principal Conductor DARLENE RONALD Director of Marketing DALE SULYMKA Chief Financial Officer 2020/21 Board of Trustees Paul Bruch-Wiens Timothy E. Burt Judith Chambers Maria Mitousis Dr. Bill Pope Alex Robinson SECRETARY CFA; Senior Vice-President VICE CHAIR Principal, Mitousis Lemieux Retired, Registrar, College of Business Development Private Wealth Manager, and Chief Market Strategist, BCom, CFP, TEP; Vice President Howard Law Corporation Physicians & Surgeons Manager, Graham Construction Quadrant Private Wealth Cardinal Capital Management, & Market Manager, TD Wealth and Engineering Inc. -

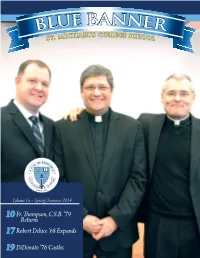

2014 Spring/Summer

bbllue banner HAEL’S COLLEGE SC ST. MIC HOOL Volume 16 ~ Spring/Summer 2014 10 Fr. ompson, C.S.B. ’79 Returns 17 Robert Deluce ’68 Expands 19 DiDonato ’76 Castles lettersbb tol theu editore banner HAEL’S COLLEGE S ST. MIC CHOOL The St. Michael’s College School alumni magazine, Blue Banner, is published two times per year. It reflects the history, accomplishments and stories of graduates and its purpose is to promote collegiality, respect and Christian values under the direction of the Basilian Fathers. PRESIDENT: Terence M. Sheridan ’89 CONTACT DIRECTORY EDITOR: Gavin Davidson ’93 St. Michael’s College School: www.stmichaelscollegeschool.com CO-EDITOR: Michael De Pellegrin ’94 Blue Banner Online: www.mybluebanner.com CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Basilian Fathers: www.basilian.org Kimberley Bailey, Michael Flood ’87, Jillian Kaster, Pat CISAA (Varsity Athletic Schedule): www.cisaa.ca Mancuso ’90, Harold Moffat ’52, Marc Montemurro ’93, Twitter: www.twitter.com/smcs1852 Joe Younder ’56, Stephanie Nicholls, Terence Sheridan Advancement Office: [email protected] ’89. Alumni Affairs: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Archives Office: [email protected] Blue Banner Feedback: [email protected] School Administration Message 4 Communications Office: [email protected] Alumni Association Message 5 Tel: 416-653-3180 ext. 292 Editor’s Letter 6 Fax: 416-653-8789 Letters to the Editor 7 E-mail: [email protected] Around St. Mike’s 8 • Admissions (ext. 195) Fr. Thompson, C.S.B. ’79 10 • Advancement (ext. 118) Returns Home as New President • Alumni Affairs (ext. 273) Securing Our Future by Giving Back: 12 Michael Flood ’87 • Archives (ext. -

Tv Pg6 08-07.Indd

6 The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, August 7, 2012 All Central Time, for Kansas Mountain TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening August 7, 2012 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 35 NFL 67 Bravo 22 ESPN 41 Hallmark ABC Middle Last Man Wipeout NY Med Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle 37 USA 68 truTV 23 ESPN 2 45 NFL CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles Person of Interest Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 24 ESPN Nws 47 Food NBC XXX Summer Olympics Local Olympics 38 TBS 71 SCI FI 3 KWGN WB 3 NBC-KUSA 25 TBS 49 E! FOX MasterChef Local 39 WGN 72 Spike 4 ABC-KLBY Cable Channels 5 KSCW WB 26 Animal 51 Travel A&E 40 TNT 73 Comedy 6 Weather 27 VH1 54 MTV Shipping Shipping Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Wars Local 6 ABC-KLBY AMC Hidalgo Sahara Local 41 FX 74 MTV 7 CBS-KBSL 28 TNT 55 Discovery ANIM 7 KSAS FOX 8 NBC-KSNK Super Croc Drug Kingpin Hippos Super Snake Super Croc Hippos Local 42 Discovery 75 VH1 29 CNBC 56 Fox Nws BET Four Brothers Hot Boyz Wendy Williams Show Belly 2 Local 8 NBC-KSNK 9 Eagle 30 FSN RM 57 Disney BRAVO 43 TLC 76 CMT Million Dollar LA Million Dollar LA Happens Love Broker Love Broker NYC 9 NBC-KUSA 11 QVC 31 CMT 58 History CMT Local Local Reba Reba Reba Reba National Lamp. -

Local Volleyball Centralia Printing a Cappella at Centralia College

Mill Lane Winery: New Winery Opens Tomorrow in Tenino / Main 14 Cowlitz Wildlife Refuge Kosmos Release Site Fosters Pheasant Hunting Fun / Sports: Outdoors $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, Sept. 27, 2012 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Mossyrock Park Advocate Wins Statewide Award / Main 3 Centralia Printing Historic Downtown Building to Sell Inventory, A Cappella at Repurpose as Apartments and Offices / Centralia College Local Volleyball Main 12 LC Concerts to Host Vocalists / Life: A&E Scores & Stats / Sports Tumultuous Tenino Recalls, Scandal, Illegal Use of Office and the State of Affairs in a Once Quiet Thurston County Town By Kyle Spurr “I didn’t break any laws,” [email protected] Strawn told the audience Tues- day night. “I probably broke a ‘‘Integrity has been compromised across the board.’’ TENINO — Residents of this few people’s support.” once quiet city spoke up Tuesday While the mayor defends his Wayne Fournier Tenino City Councilor night as a standing-room only innocence, Councilor Robert crowd challenged the city council Scribner was discovered to have for bringing consistent controver- used resources when working at sy to the south Thurston County the Washington State Depart- town over the past eight months. ment of Labor and Industries in ‘‘I didn’t break any laws. I probably broke a In the past two weeks alone, June to access personal and con- the city’s mayor, Eric Strawn, fidential records on the mayor few people’s support.’’ was accused of having sexual and other city employees, ac- Eric Strawn contact with a woman inside a cording to internal investigation city vehicle, but did not face any Mayor of the City of Tenino charges for the incident. -

A Study of Selected Reality Television Franchises in South Africa And

GLOCALISATION WITHIN THE MEDIA LANDSCAPE: A Study of Selected Reality Television Franchises in South Africa and Transnational Broadcaster MultiChoice BY Rhoda Titilopemi Inioluwa ABIOLU Student number 214580202 Ethical clearance number HSS/1760/015M A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Social Sciences in the Centre for Communication, Media and Society (CCMS), College of Humanities, School of Applied Human Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal. Supervised by: Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli UNESCO Chair of Communications FEBRUARY, 2017. DECLARATION I, Rhoda Titilopemi Inioluwa ABIOLU (214580202) declare that this research is my original work and has not been previously submitted in part or whole for any degree or examination at any other university. Citations, references and writings from other sources used in the course of this work have been acknowledged. Student’s signature………………………………… Date…………………………………. Supervisor’s signature……………………………… Date………………………………… ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my Father, my Saviour, my Friend and my God, Jesus Christ; the Source of all good things, the Author and Finisher of my faith who helped me and gave me the courage and strength to do this work, ESEUN OLUWAAMI. I thank my supervisor Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli, who stirred up the interest in this field through the MGW module. I thank you for all your guidance through this work and for all you did. How you always make time for me is deeply cherished. You are a source of encouragement. Thank you Prof. The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. -

Yosemite Conservancy Autumn.Winter 2011 :: Volume 02

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY AUTUMN.WINTER 2011 :: VOLUME 02 . ISSUE 02 Majestic Wonders Beyond the Valley INSIDE Campaign for Yosemite’s Trails Update Restoration Efforts at Tenaya Lake Wawona Fountains Rehabilitated Q&A With Ostrander Hut Keeper COVER PHOTO: © NANCY ROBBINS, “GRIZZLY GIANT”. PHOTO: (RIGHT) © NANCY ROBBINS. (RIGHT) © NANCY GIANT”. PHOTO: “GRIZZLY ROBBINS, © NANCY PHOTO: COVER PRESIDENT’S NOTE Beyond the Valley inter is a welcome time of year in Yosemite. The visitors who have enjoyed the park YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY Win numbers all season long COUNCIL MEMBERS gradually subside with the cooling CHAIRMAN PRESIDENT & CEO temperatures. Before the first snows, the John Dorman* Mike Tollefson* forests radiate with fall foliage and begin VICE CHAIR VICE PRESIDENT to drop their leaves. It’s a time to reflect Christy Holloway* & COO Jerry Edelbrock on the summer season and give thanks for the supporters who made it all possible. COUNCIL Jeanne & Michael Anahita & Jim Lovelace Throughout this issue, we go beyond the Valley and explore Adams Carolyn & Bill Lowman highlights from summer projects and programs and look toward Lynda & Scott Adelson Dick & Ann* Otter winter activities, like those at Ostrander Ski Hut. Our Expert Insider, Gretchen Augustyn Norm & Janet Pease Meg & Bob Beck Sharon & Phil* Gretchen Stromberg, describes the restoration efforts which began Susie & Bob* Bennitt Pillsbury on Tenaya Lake’s East Beach. Read about visitors who connected Barbara Boucke Arnita & Steve Proffitt David Bowman & Bill Reller with the park through projects like Ask-A-Climber or gathered in Gloria Miller Frankie & Skip* Rhodes rehabilitated campground amphitheaters. Others joined programs, Allan & Marilyn Brown Angie Rios & Samuel Don & Marilyn Conlan Norman like those at the Yosemite Art Center or Valley Theater, and left with Hal Cranston* Liz & Royal Robbins special memories.