1.9 Large-Scale Regreening in Niger: Lessons for Policy and Practice —

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Appendix

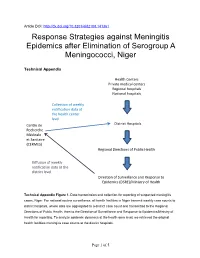

Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2108.141361 Response Strategies against Meningitis Epidemics after Elimination of Serogroup A Meningococci, Niger Technical Appendix Health Centers Private medical centers Regional hospitals National hospitals Collection of weekly notification data at the health center level Centre de District Hospitals Recherche Médicale et Sanitaire (CERMES) Regional Directions of Public Health Diffusion of weekly notification data at the district level Direction of Surveillance and Response to Epidemics (DSRE)/Ministry of Health Technical Appendix Figure 1. Data transmission and collection for reporting of suspected meningitis cases, Niger. For national routine surveillance, all health facilities in Niger transmit weekly case counts to district hospitals, where data are aggregated to a district case count and transmitted to the Regional Directions of Public Health, then to the Direction of Surveillance and Response to Epidemics/Ministry of Health for reporting. To analyze epidemic dynamics at the health area level, we retrieved the original health facilities meningitis case counts at the district hospitals. Page 1 of 5 Evaluation of Completeness of the Health Center Database The country has 8 regions (Tahoua, Tillabery, Agadez, Diffa, Maradi, Niamey, Zinder, and Dosso), 42 districts, and 732 health areas containing >1,500 health centers. To assess the completeness of this database, we compared the resulting district-level weekly case counts with those included in the national routine surveillance reports. A -

Dynamique Des Conflits Et Médias Au Niger Et À Tahoua Revue De La Littérature

Dynamique des Conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua Revue de la littérature Décembre 2013 Charline Burton Rebecca Justus Contacts: Charline Burton Moutari Aboubacar Spécialiste Conception, Suivi et Coordonnateur National des Evaluation – Afrique de l’Ouest Programmes - Niger Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire [email protected] + 227 9649 00 39 [email protected] +225 44 47 24 57 +227 90 60 54 96 Dynamique des conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua | PAGE 2 Table des matières 1. Résumé exécutif ...................................................................................................... 4 Contexte ................................................................................................. 4 Objectifs et méthodologie ........................................................................ 4 Résultats principaux ............................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Contexte de la revue de littérature ............................................................... 7 2.2 Méthodologie et questions de recherche ....................................................... 7 3. Contexte général du Niger .................................................................................. 10 3.1 Démographie ............................................................................................. 10 3.2 Situation géographique et géostratégique ............................................ -

Collective Action and the Deployment of Teachers in Niger a Political Economy Analysis

Briefing Collective action and the deployment of teachers in Niger A political economy analysis Clare Cummings and Ali Bako M. Tahirou with Hamissou Rhissa, Falmata Hamed, Hamadou Goumey, and Idi Mahamadou Mamane Noura January 2016 • The system of teacher deployment and distribution is undermined by the personal interests of Key teachers. messages • There is a lack of incentives for administrators or political leaders to uphold the formal rules of teacher deployment and distribution. • There is a lack of regulations, accountability mechanisms and sanctions governing the distribution of teachers. • Parents and pupils who could benefit from a more equitable distribution of teachers lack influence over the system, may lack the means to engage in the problem, and are more likely to find individual solutions. • Collective action for better public education is rare. Most instances of collective action related to education are either teachers’ unions seeking high teacher wages, or local communities working together to manage a schools’ resources, usually led by an NGO or government initiative. While teachers’ unions state that they may call on their members to respect the placements which they are given, collective action by unions or communities does not directly address the problem of teacher distribution. • The problem of teacher distribution is systemic and is maintained by misaligned political and financial incentives within the education system. The recommendations suggest a reform to the system which would alter incentives and motivate changed behaviour over the deployment and transfer of teachers. Shaping policy for development developmentprogress.orgodi.org Introduction The problem of teacher deployment This research aims to examine the potential for collective action to address the problem of inequitable teacher Key issues deployment in Niger. -

Migration and Markets in Agadez Economic Alternatives to the Migration Industry

Migration and Markets in Agadez Economic alternatives to the migration industry Anette Hoffmann CRU Report Jos Meester Hamidou Manou Nabara Supported by: Migration and Markets in Agadez: Economic alternatives to the migration industry Anette Hoffmann Jos Meester Hamidou Manou Nabara CRU Report October 2017 Migration and Markets in Agadez: Economic alternatives to the migration industry October 2017 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: Men sitting on their motorcycles by the Agadez market. © Boris Kester / traveladventures.org Unauthorised use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Anette Hoffmann is a senior research fellow at the Clingendael Institute’s Conflict Research Unit. -

Niger 2020 Human Rights Report

NIGER 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Niger is a multiparty republic. In the first round of the presidential elections on December 27, Mohamed Bazoum of the ruling coalition finished first with 39.3 percent of the vote. Opposition candidate Mahamane Ousman finished second with 16.9 percent. A second round between the two candidates was scheduled for February 21, 2021. President Mahamadou Issoufou, who won a second term in 2016, was expected to continue in office until the second round was concluded and the winner sworn into office. International and domestic observers found the first round of the presidential election to be peaceful, free, and fair. In parallel legislative elections also conducted on December 27, the ruling coalition preliminarily won 80 of 171 seats, and various opposition parties divided the rest, with several contests still to be decided. International and local observers found the legislative elections to be equally peaceful, free, and fair. The National Police, under the Ministry of Interior, Public Security, Decentralization, and Customary and Religious Affairs (Ministry of Interior), is responsible for urban law enforcement. The Gendarmerie, under the Ministry of National Defense, has primary responsibility for rural security. The National Guard, also under the Ministry of Interior, is responsible for domestic security and the protection of high-level officials and government buildings. The armed forces, under the Ministry of National Defense, are responsible for external security and, in some parts of the country, for internal security. Every 90 days the parliament reviews the state of emergency declaration in effect in the Diffa Region and in parts of Tahoua and Tillabery Regions. -

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger Analysis Coordination March 2019 Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Acknowledgements This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

RIFT VALLEY FEVER in NIGER Risk Assessment

March 2017 ©FAO/Ado Youssouf ©FAO/Ado ANIMAL HEALTH RISK ANALYSIS ASSESSMENT No. 1 RIFT VALLEY FEVER IN NIGER Risk assessment SUMMARY In the view of the experts participating in this risk assessment, Rift Valley Fever (RVF) in Niger currently poses a medium risk (a mean score of 5.75 on a scale of 0 to 10) to human health, and a medium–high risk (a mean score of 6.5) to animal health. The experts take the view that RVF is likely / very likely (a 66%–99% chance range) to occur in Mali during this vector season. Its occurrence in the neighbouring countries of Benin, Burkina Faso and Nigeria is considered less probable – between unlikely (a 10%–30% chance) and as likely as not (a 33%–66% chance). The experts are of the opinion that RVF isunlikely to spread into Algeria, Libya or Morocco in the next three to five years. Animal movements, trade and changes in weather conditions are the main risk factors in RVF (re)occurring in West Africa and spreading to unaffected areas. Improving human health and the capacities of veterinary services to recognize the clinical signs of RVF in humans and animals are crucial for rapid RVF detection and response. Finally, to prevent human infection, the most feasible measure is to put in place communication campaigns for farmers and the general public. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SITUATION FIGURE 1. Human cases of RVF in Niger Between 2 August and 9 October 2016, Niger reported 101 human cases of suspected RVF, including 28 deaths. All RVF cases were in Tchintabaraden and Abalak health districts in the Tahoua region (Figure 1). -

Insecurity, Terrorism, and Arms Trafficking in Niger

Small Arms Survey Maison de la Paix Report Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E January 1202 Geneva 2018 Switzerland t +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] At the Crossroads of Sahelian Conflicts Sahelian of the Crossroads At About the Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is a global centre of excellence whose mandate is to generate impar- tial, evidence-based, and policy-relevant knowledge on all aspects of small arms and armed AT THE CROSSROADS OF violence. It is the principal international source of expertise, information, and analysis on small arms and armed violence issues, and acts as a resource for governments, policy- makers, researchers, and civil society. It is located in Geneva, Switzerland, at the Graduate SAHELIAN CONFLICTS Institute of International and Development Studies. The Survey has an international staff with expertise in security studies, political science, Insecurity, Terrorism, and law, economics, development studies, sociology, and criminology, and collaborates with a network of researchers, partner institutions, non-governmental organizations, and govern- Arms Trafficking in Niger ments in more than 50 countries. For more information, please visit: www.smallarmssurvey.org. Savannah de Tessières A publication of the Small Arms Survey/SANA project, with the support of the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Global Affairs Canada, and the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs A T THE CROSSROADS OF SAHELian CONFLictS Insecurity, Terrorism, and Arms Trafficking in Niger Savannah de Tessières A publication of the Small Arms Survey/SANA project, with the support of the Netherlands Min. of Foreign Affairs, Global Affairs Canada, & the Swiss Federal Dept. -

Sahel Situation (Tillabery and Tahoua Regions) February 2021

NIGER UPDATE: SAHEL SITUATION Sahel situation (Tillabery and Tahoua regions) February 2021 The Sahel regions have been The rapidly deteriorating security The presence of armed groups hosting some 60,000 Malian context has caused increased across the border has caused refugees since 2012. They live in 3 internal displacement flows with movements of a few thousand sites in the Tillabery region and a rising numbers every month. To citizens from Burkina Faso refugee hosting area in the Tahoua date, some 140,000 IDPs are into Niger. region. present in both regions. FUNDING (AS OF 2 FEBRUARY 2021) KEY INDICATORS 40,000* USD 110,5 M Number of refugees in Niger who will have access to land requested for UNHCR’s operations in Niger according to the Government's pledge during the Global Funded 20% Refugee Forum. 18.7 USD +50%* Increase of the number of internally displaced persons since last year. 374 Durable houses built and finalized in the Tillabery Unfunded 80% region 91.8 USD POPULATION OF CONCERN IN NIGER'S SAHEL (UNHCR data, 31 January 2021) Internal displaced 138 229 persons Malian Refugees 60 236 People from Burkina Faso 3 937 www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > Niger· Sahel / February 2021 Update on Achievements Operational Context Malian Refugees Evolution of Displaced persons in Niger IDPs Burkina faso Refugees 941 780 780 780 763 780 107 033 108 097 030 139 138229 138229 138229 139 139 95 140 139 97 137 88 144 435 232 847 548 613 442 959 599 702 60185 60244 60236 59 59 59 59 59 58 58 58 58 58 3 170 3 170 3 332 3 332 3 514 3 514 3 514 3 803 3 803 3 803 3 803 3 803 3 937 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan 2020 2021 Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso are all struggling to cope with numerous militant groups moving between the three countries. -

NIGER Humanitarian Situation

j NIGER Humanitarian Situation Report No. 06 UNICEFNiger/J.Haro @ Reporting Period: 01 to 30 June 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers • Gunmen suspected to be militants of non-state armed groups (NSAGs) regularly 1.6 million carried out asymmetric attacks against military outposts and patrols in Tillaberi children in need of humanitarian assistance and Diffa regions. On June 24th, dozens of civilians were abducted in Diffa and 2.9 million Tillaberi regions, including 12 staffs from a United Nations implementing people in need (OCHA, Humanitarian partner, in Bossey-Bangou (Tillaberi). Response Plan Niger, 2020) • 24 children between 12 and 15 years old (11 girls) were kidnapped by non-state 396,539 armed group members in Toumour and Gueskerou communes. The incidents children affected by SAM nationwide happened during night attacks. Compared to last month, children abduction has (OCHA, Humanitarian Response Plan Niger, increased in the month of June with a total of 24 children abducted by NSAGs. 2020) • In June 2020, the Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) recorded 6 alerts on 54,148 displacement of people following non-state army groups attacks. Rapid Internally displaced children in assessments (9 multi-sector assessments, 8 rapid protection assessments and 1 Tillaberi / Tahoua, out of flash assessment) were conducted in the Diffa, Tahoua, Tillaberi and Maradi 95,033 regions. RRM actors also provided NFI assistance to approximately 280 displaced Internally displaced people in households for 1,955 beneficiaries. Tillaberi / Tahoua (UNHCR, Feb 2020) • Instability in the region, leading to humanitarian access challenges, as well as the 24,120 insufficiency of funding to support child protection in emergency activities, remain key issues in Diffa region. -

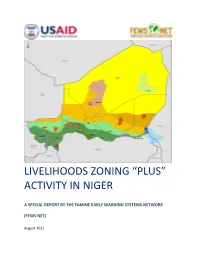

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Cholera Country Profile: Niger

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Global Task Force on Cholera Control Last update: 5 February 2013 CHOLERA COUNTRY PROFILE: NIGER General Country Information: The Republic of Niger is a landlocked sub-Saharan country in Western Africa, named after the Niger River. It borders Nigeria and Benin to the south, Burkina Faso and Mali to the west, Algeria and Libya to the north and Chad to the east. Its capital and largest city is Niamey. In 1922, Niger was colonized by France and French became the official language. The 1946 French constitution provided for decentralization of power. Since 1960, Niger is fully independent. In February 2010, a coup d'état occurred in Niamey and soldiers captured President Mamadou Tandja. The country was then headed by a ruling junta. A new president has been elected in February 2011. Niger's subtropical - tropical climate is mainly hot and dry, with a large deserted area. Its economy is based on farming, livestock and some of the world's largest uranium deposits. But drought cycles, desertification, grasshopper invasion, 3.3% population growth rate and the drop in world demand for uranium have undercut an already marginal economy. Niger faces chronic nutritional emergencies and the lack of rain falls in 2011 will impact food production. Malaria causes more deaths each year in Niger among children under five years of age than any other single infection. Cholera Background History: Niger had several severe outbreaks from 1970 to 20 11 but without periodical pattern. However since 1994, there is a yearly occurrence except for 1998 and 2009. The largest outbreak occurred in 1971 w ith 9265 cases and 2344 deaths with a very high case fatality rate (CFR) of 25.3% .