Creativity & Cultural Production in the Hunter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

ARIA COUNTRY ALBUMS CHART WEEK COMMENCING 5 APRIL, 2021 TW LW TI HP TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TW THIS WEEK LW LAST WEEK TI TIMES IN HP HIGH POSITION ARIA COUNTRY ALBUMS CHART WEEK COMMENCING 5 APRIL, 2021 TW LW TI HP TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 2 73 1 WHAT YOU SEE AIN'T ALWAYS WHAT YOU GET Luke Combs <P> COL/SME 19075956872 2 3 12 1 DANGEROUS: THE DOUBLE ALBUM Morgan Wallen UNI/UMA B003318002 3 4 199 1 THIS ONE'S FOR YOU Luke Combs <P> COL/SME 19075829282 4 1 2 1 THE WORLD TODAY Troy Cassar-Daley SME 19439857022 5 NEW 1 5 LIVIN' ON GOLD STREET Ben Mastwyk SFR SHRIMP03CD 6 NEW 1 6 MY SAVIOR Carrie Underwood CAP/UMA 3560505 7 8 107 3 IF I KNOW ME Morgan Wallen UMA 1210656 8 NEW 1 8 BRAVE NEW WORLD Ben Ransom MGM CR1005 9 5 2 5 J.T. Steve Earle & The Dukes NW/INE NW6511CD 10 10 402 1 SPEAK NOW Taylor Swift <P>2 BIG/UMA 2749395 11 12 118 2 GENUINE: THE ALAN JACKSON STORY Alan Jackson RCA/SME 88725406392 12 11 28 1 THE SPEED OF NOW PART 1 Keith Urban CAP/EMI B003245602 13 6 6 1 SONGS FROM HIGHWAY ONE Adam Harvey SME 19439764762 14 15 7 4 LIFE ROLLS ON Florida Georgia Line UMA 3006012 15 13 498 1 THE VERY BEST OF DOLLY PARTON Dolly Parton <P> RCA/SME 88697060742 16 16 20 2 STARTING OVER Chris Stapleton MER/UMA 3503003 17 17 44 4 DIPLO PRESENTS THOMAS WESLEY CHAPTER 1: SNAKE OIL Diplo COL/SME G010004279022H 18 7 5 5 THAT'S LIFE Willie Nelson LEG/SME 19439839452 19 20 270 3 TRAVELLER Chris Stapleton MER/UMA 3757743 20 R/E 3 2 TOWN OF A MILLION DREAMS Casey Barnes CHUGG/MGM CHG021 21 19 11 4 CREAM OF COUNTRY 2021 Various SME 19439840112 22 18 128 1 THINGS THAT WE DRINK TO Morgan Evans WAR 9362490549 23 21 125 1 EXPERIMENT Kane Brown RCA/SME 19075867532 24 23 169 1 STORYTELLER Carrie Underwood ARI/SME 88875105392 25 24 34 1 BORN HERE LIVE HERE DIE HERE Luke Bryan CAP/UMA B003177702 26 25 54 15 COUNTRY MUSIC - A FILM BY KEN BURNS Soundtrack LEG/SME 19075960422 27 26 19 7 HEY WORLD Lee Brice CURB/SME D2-79537 28 29 1141 1 THE VERY BEST OF Slim Dusty <P>5 EMI 3743287 29 R/E 181 11 ULTIMATE.. -

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising Awards • AFI Awards • AICE & AICP (US) • Akil Koci Prize • American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal in Music • American Cinema Editors • Angers Premier Plans • Annie Awards • APAs Awards • Argentine Academy of Cinematography Arts and Sciences Awards • ARIA Music Awards (Australian Recording Industry Association) Ariel • Art Directors Guild Awards • Arthur C. Clarke Award • Artios Awards • ASCAP awards (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) • Asia Pacific Screen Awards • ASTRA Awards • Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTS) • Australian Production Design Guild • Awit Awards (Philippine Association of the Record Industry) • BAA British Arrow Awards (British Advertising Awards) • Berlin International Film Festival • BET Awards (Black Entertainment Television, United States) • BFI London Film Festival • Bodil Awards • Brit Awards • British Composer Awards – For excellence in classical and jazz music • Brooklyn International Film Festival • Busan International Film Festival • Cairo International Film Festival • Canadian Screen Awards • Cannes International Film Festival / Festival de Cannes • Cannes Lions Awards • Chicago International Film Festival • Ciclope Awards • Cinedays – Skopje International Film Festival (European First and Second Films) • Cinema Audio Society Awards Cinema Jove International Film Festival • CinemaCon’s International • Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards – An annual awards program bestowed by Classic Rock Clio -

Dutch Visitors K-6 Foundation

MAGAZINE PIN OAK ISSUE 16: TERM 2, MAY 15, 2015 Foundation Day Dutch Visitors K-6 Contents 3 Headmaster’s Report 4 Big Issue 5 Films, Music, Books 6 K - 6 News 7 More K-6 MINDFULNESS 8 Feature Article Have you ever had a moment when all you can think about is how stressed you are about how you 10 Deputy Reports : Learning & Pastoral haven’t finished the assignment that is due this week or you are really worried because you think In the Spotlight that you failed the exam last week. Seriously! Chill! 11 You need to bring yourself back to the moment and MusicArtDrama think about what is going on right now! This is called 12 mindfulness. On the Branch John Teasdale invented the cognitive theory of 13 Mindfulness in 1991. To practice mindfulness we Gallery need to be aware of where we are, what we are 14 feeling and what is going on right now? To be mindful we need to notice when we are worrying 15 Calendar about the future or stressing about what has happened in the past and bring ourselves back to the 16 Sport moment we are in. After all we can’t change what’s already happened and the only way to influence the future is to achieve something in the present. Being Pin Oak Team in the moment can also benefit our relationships Student Editorial Team because we are more present to the people around Alexia Cheaib, Ruben Seaton, Evangeline us. We listen more effecively and engage more. To Larsen, Evelyn Bratchford, Ryan Tan, Kaarina get your mind back in the moment, become aware of Allen, Maddie Thomas, Heidi Bevan, Cate your senses. -

Terms and Lingo – the Roadie’S Lexicon for the Layman

Terms and Lingo – The Roadie’s Lexicon for the Layman A handy and fun selection of Terms and Lingo used throughout the industry, some serious, and some not so! ACOUSTICS – the science of sound; invented to make otherwise good sound men look like complete fools. AIR IMPEDANCE – also known as not plugged in. APRON – front edge of stage. BACKLOUNGE – rear section of a tour bus, generally the smoking area. BACKLINE – band equipment which is not an actual instrument, but some type of reinforcement equipment, for example Amplifiers. BAND ENGINEER – person who mixes the group. BEST BOY – movie term for the lead assistant electrician answering to the gaffer. BOAT ANCHOR – a piece of heavy equipment which isn’t performing to expectations and has been presumed dead, or is otherwise obsolete. BUMPERS – sturdy frames from which speakers are hung. BUS FACTOR – the degree to which bad movies improve due to extended bus rides. Lower bus factor is better, but requires better movies. Formula: B = DMN/S Where: B = Bus factor, D = Bus time (# days on bus), M = Distance (# miles), N = Number of passengers on bus, S = Bus stock (# gallons of alcoholic beverages). BUS STOCK – consumables stored in the bus. BUS SURFING – the art of walking and/or standing upright on a moving bus. BUS HAIR – what you get if you go to sleep with wet hair. Stagecraft Technical Services Ltd. Tel: 0845 838 2015 Email: [email protected] Fax: 0845 838 2016 Website: www.stagecraft.co.uk CABLE MONKEY – an entry level roadie position, one who wrangles cables. CABLE RAMP – neither actually, a portable trough used to place cable to allow traffic to cross a cable run. -

Technical Crew Information Performance Dates: October 20 (3 & 7 PM) October 21 (3 PM)

Technical Crew Information Performance Dates: October 20 (3 & 7 PM) October 21 (3 PM) Thank you for your interest in being on the Tech Crew for the McDuffee Music Studio 2018 Musical Theatre Production of Disney’s The Little Mermaid Jr. There are 5 different possible Crew positions available for students in 5th – 12th grades at any school, up to 15 people max. Each crew position is vital to the success of a show and the responsibilities should be taken seriously. Sign ups are open now and will close when all the spots are filled, on a first-come, first-served basis. Being part of any production requires commitment and hard-work. I compare theater to a team-sport: EVERYONE is important and necessary. I have told the cast that Sea Urchin #3 is every bit as important as Ariel in this production. The Technical Crew is just as important as the people on the stage as well. BEFORE YOU SIGN UP, PLEASE CONSIDER ALL OF THE FOLLOWING: DATES/TIME COMMITTMENT: Please double check family, school, and extra-curricular calendars against the schedule below. You need to be at all of the above rehearsals for their full times. Crew members need to be at ALL of the following rehearsals: • 10/10 (Wed) 5 – 8 PM at Faith United Church of Christ (Faith UCC – 4040 E Thompson Rd) o 5 - 6: we will meet and discuss the positions and answer any questions o 6 – 8: we watch the run of the show so that the crew can start to become familiar with the production. -

Australian Events 2016 Major Events, Australia - from September 2016 to February 2017

AUSTRALIAN EVENTS 2016 MAJOR EVENTS, AUSTRALIA - FROM SEPTEMBER 2016 TO FEBRUARY 2017 Month Event Date More Info ADELAIDE, SOUTH AUSTRALIA January Australia Day 26 January, 2017 australiadayinthecity.com.au BRISBANE, QUEENSLAND September Brisbane Festival 3-24 September, 2016 brisbanefestival.com.au January Australia Day 26 January, 2017 qld.australiaday.org.au February Brisbane Comedy Festival 27 February – 23 March, 2016 brisbanepowerhouse.org/festivals/brisbane-comedy- festival-2016/ CANBERRA, AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY September Floriade 17 September – 16 October, floriadeaustralia.com 2016 January Australia Day 26 January, 2017 australiaday.org.au/act DARWIN, NORTHERN TERRITORY December New Year’s Eve Concert and 31 December, 2016 northernterritory.com/sitecore/atdw/regions/darwin- Fireworks and-surrounds/events/9002710 January Australia Day 26 January, 2017 nt.australiaday.org.au GOLD COAST, QUEENSLAND October Gold Coast 600 21-23 October, 2016 supercars.com/gold-coast January Australia Day 26 January, 2017 goldcoast.qld.gov.au/thegoldcoast/australia-day- celebrations-20389.html MACKAY, QUEENSLAND September Pioneer Valley Country Music 30 September – 2 October, 2016 mackayregion.com/events/event/100442-pioneer- Festival valley-country-music-festival January Australia Day 26 January, 2017 qld.australiaday.org.au MELBOURNE, VICTORIA September Royal Melbourne Show 17-27 September, 2016 royalshow.com.au Spring Racing Carnival 1 September, 2016 springracingcarnival.com.au October AFL Grand Final 1 October, 2016 afl.com.au November Melbourne -

Media Tracking List Edition January 2021

AN ISENTIA COMPANY Australia Media Tracking List Edition January 2021 The coverage listed in this document is correct at the time of printing. Slice Media reserves the right to change coverage monitored at any time without notification. National National AFR Weekend Australian Financial Review The Australian The Saturday Paper Weekend Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 2/89 2021 Capital City Daily ACT Canberra Times Sunday Canberra Times NSW Daily Telegraph Sun-Herald(Sydney) Sunday Telegraph (Sydney) Sydney Morning Herald NT Northern Territory News Sunday Territorian (Darwin) QLD Courier Mail Sunday Mail (Brisbane) SA Advertiser (Adelaide) Sunday Mail (Adel) 1st ed. TAS Mercury (Hobart) Sunday Tasmanian VIC Age Herald Sun (Melbourne) Sunday Age Sunday Herald Sun (Melbourne) The Saturday Age WA Sunday Times (Perth) The Weekend West West Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 3/89 2021 Suburban National Messenger ACT Canberra City News Northside Chronicle (Canberra) NSW Auburn Review Pictorial Bankstown - Canterbury Torch Blacktown Advocate Camden Advertiser Campbelltown-Macarthur Advertiser Canterbury-Bankstown Express CENTRAL Central Coast Express - Gosford City Hub District Reporter Camden Eastern Suburbs Spectator Emu & Leonay Gazette Fairfield Advance Fairfield City Champion Galston & District Community News Glenmore Gazette Hills District Independent Hills Shire Times Hills to Hawkesbury Hornsby Advocate Inner West Courier Inner West Independent Inner West Times Jordan Springs Gazette Liverpool -

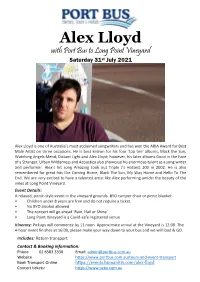

Alex Lloyd with Port Bus to Long Point Vineyard Saturday 31St July 2021

Alex Lloyd with Port Bus to Long Point Vineyard Saturday 31st July 2021 Alex Lloyd is one of Australia’s most acclaimed songwriters and has won the ARIA Award for Best Male Artist on three occasions. He is best known for his four ‘top ten’ albums, Black the Sun, Watching Angels Mend, Distant Light and Alex Lloyd; however, his later albums Good in the Face of a Stranger, Urban Wilderness and Acoustica also showcase his enormous talent as a song writer and performer. Alex’s hit song Amazing took out Triple J’s Hottest 100 in 2002. He is also remembered for great hits like Coming Home, Black The Sun, My Way Home and Hello To The End. We are very excited to have a talented artist like Alex performing amidst the beauty of the vines at Long Point Vineyard. Event Details: A relaxed, picnic-style event in the vineyard grounds. BYO camper chair or picnic blanket. • Children under 8 years are free and do not require a ticket. • No BYO alcohol allowed • The concert will go ahead ‘Rain, Hail or Shine’ • Long Point Vineyard is a Covid-safe registered venue Itinerary: Pickups will commence by 11 noon. Approximate arrival at the Vineyard is 12:00. The 4-hour event finishes at 16:00, please make your way down to your bus and we will load & GO. Includes: Return transport Contact & Booking information: Phone 02 6583 3330 Email: [email protected] Website https://www.portbus.com.au/tours-and-event-transport Book Transport Online https://events.humanitix.com/alex-lloyd Concert tickets: https://www.oztix.com.au . -

Annual Financial Report 30 June 2020

Australasian Performing Right Association Limited (a company limited by guarantee) and its controlled entity ABN 42 000 016 099 Annual Financial Report 30 June 2020 Australasian Performing Right Association Limited and its controlled entity Annual Report 30 June 2020 Directors’ report For the year ended 30 June 2020 The Directors present their report together with the financial statements of the consolidated entity, being the Australasian Performing Right Association Limited (Company) and its controlled entity, for the financial year ended 30 June and the independent auditor’s report thereon. Directors The Directors of the Company at any time during or since the financial year are: Jenny Morris OAM, MNZM Non-executive Writer Director since 1995 and Chair of the Board A writer member of APRA since 1983, Jenny has been a music writer, performer and recording artist since 1980 with three top 5 and four top 20 singles in Australia and similar success in New Zealand. Jenny has recorded nine albums gaining gold, platinum and multi-platinum status in the process and won back to back ARIA awards for best female vocalist. Jenny was inducted into the NZ Music Hall of Fame in 2018. Jenny is also a non-executive director and passionate supporter of Nordoff Robbins Music Therapy Australia. Jenny presents their biennial ‘Art of Music’ gala event, which raises significant and much needed funds for the charity. Bob Aird Non-executive Publisher Director from 1989 to 2019 Bob recently retired from his position as Managing Director of Universal Music Publishing Pty Limited, Universal Music Publishing Group Pty Ltd, Universal/MCA Publishing Pty Limited, Essex Music of Australia Pty Limited and Cromwell Music of Australia Pty Limited which he held for 16 years. -

M-Phazes | Primary Wave Music

M- PHAZES facebook.com/mphazes instagram.com/mphazes soundcloud.com/mphazes open.spotify.com/playlist/6IKV6azwCL8GfqVZFsdDfn M-Phazes is an Aussie-born producer based in LA. He has produced records for Logic, Demi Lovato, Madonna, Eminem, Kehlani, Zara Larsson, Remi Wolf, Kiiara, Noah Cyrus, and Cautious Clay. He produced and wrote Eminem’s “Bad Guy” off 2015’s Grammy Winner for Best Rap Album of the Year “ The Marshall Mathers LP 2.” He produced and wrote “Sober” by Demi Lovato, “playinwitme” by KYLE ft. Kehlani, “Adore” by Amy Shark, “I Got So High That I Found Jesus” by Noah Cyrus, and “Painkiller” by Ruel ft Denzel Curry. M-Phazes is into developing artists and collaborates heavy with other producers. He developed and produced Kimbra, KYLE, Amy Shark, and Ruel before they broke. He put his energy into Ruel beginning at age 13 and guided him to RCA. M-Phazes produced Amy Shark’s successful songs including “Love Songs Aint for Us” cowritten by Ed Sheeran. He worked extensively with KYLE before he broke and remains one of his main producers. In 2017, Phazes was nominated for Producer of the Year at the APRA Awards alongside Flume. In 2018 he won 5 ARIA awards including Producer of the Year. His recent releases are with Remi Wolf, VanJess, and Kiiara. Cautious Clay, Keith Urban, Travis Barker, Nas, Pusha T, Anne-Marie, Kehlani, Alison Wonderland, Lupe Fiasco, Alessia Cara, Joey Bada$$, Wiz Khalifa, Teyana Taylor, Pink Sweat$, and Wale have all featured on tracks M-Phazes produced. ARTIST: TITLE: ALBUM: LABEL: CREDIT: YEAR: Come Over VanJess Homegrown (Deluxe) Keep Cool/RCA P,W 2021 Remi Wolf Sexy Villain Single Island P,W 2021 Yung Bae ft.