Community Safety Through Breed Bans?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

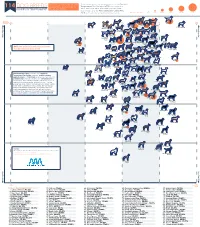

Ranked by Temperament

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

Assessment of Canine Temperament in Relation to Breed Groups 5

Temperament assessment related to breed groups S.E. Dowd 2006 Assessment of Canine Temperament in Relation to Breed Groups Scot E. Dowd Ph.D. Matrix Canine Research Institute. PO BOX 1332, Shallowater, TX 79363, [email protected] , http://www.canineresearch.org . Abstract Breed specific legislations (BSL), are laws that discriminate against dogs of specific breeds and breed groups. BSL similar to human racial profiling is based upon the premise that certain breed types are more dangerous to humans because of genetic temperament predispositions. The American Pit Bull Terrier and the American Staffordshire Terrier are the breeds most targeted by BSL. In the current study, the temperaments of over 25,000 dogs, of various breeds, have been evaluated including 1136 dogs from the pit bull group and 469 American Pit Bull Terriers. Using results of a rigorous pass-fail temperament test, designed to evaluate characteristics such as human aggression, these analyses statistically evaluated the proportion of dogs categorized by breed groups (e.g. sporting, pit bull, hound, toy, terrier) passing. Interestingly, results show that the pit bull group had a significantly higher passing proportion (p < 0.05) than all other pure breed groups, except the Sporting and Terrier groups. These groups however, did not have a statistically higher passing proportion (p = 0.78) than the pit bull group. This study has provided data to indicate the classification of dog breed groups with respect to their inherent temperament, as part of BSL, may lack scientific credibility. Breed stereotyping, like racial profiling, ignores the complex environmental factors that contribute to canine temperament and behavior. -

A Quick Assessment Tool for Humandirected Aggression in Pet

AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR Volume 9999, pages 1–11 (2013) A Quick Assessment Tool for Human‐Directed Aggression in Pet Dogs Barbara Klausz1, Anna Kis1,2, Eszter Persa1, Ádám Miklósi1,3, and Márta Gácsi1,3* 1Department of Ethology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary 2Research Centre for Natural Sciences, Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and Psychology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary 3MTA‐ELTE Comparative Ethology Research Group, Budapest, Hungary .......................................... Many test series have been developed to assess dog temperament and aggressive behavior, but most of them have been criticized for their relatively low predictive validity or being too long, stressful, and/or problematic to carry out. We aimed to develop a short and effective series of tests that corresponds with (a) the dog’s bite history, and (b) owner evaluation of the dog’s aggressive tendencies. Seventy‐three pet dogs were divided into three groups by their biting history; non‐biter, bit once, and multiple biter. All dogs were exposed to a short test series modeling five real‐life situations: friendly greeting, take away bone, threatening approach, tug‐of‐war, and roll over. We found strong correlations between the in‐test behavior and owner reports of dogs’ aggressive tendencies towards strangers; however, the test results did not mirror the reported owner‐directed aggressive tendencies. Three test situations (friendly greeting, take‐away bone, threatening approach) proved to be effective in evoking specific behavioral differences according to dog biting history. Non‐biters differed from biters, and there were also specific differences related to aggression and fear between the two biter groups. When a subsample of dogs was retested, the test revealed consistent results over time. -

Wgsdpa Bh Written Examination for Firt-Time Handlers

WGSDPA BH WRITTEN EXAMINATION FOR FIRT-TIME HANDLERS 1. The length of the leash that must be useD for the BH is: 33 Feet 3 Feet 6 Feet 2. The BH is an optional test anD the hanDler can opt to go right for the IGP 1: True False 3. The Traffic Portion of the BH is: Optional To Determine Acceptable Temperament Only requireD if you live in a metropolitan city Necessary to ensure the Dog has suitable temperament 4. For the long Down: The hanDler Disappears into a blinD The hanDler faces the Dog anD can eye signal the Dog to stay The handler’s back is to the Dog 5. The entire BH test is on leash True False 6. You can attempt the BH on Day 1 of the trial anD if you pass, attempt the IGP 1 on Day 2 True False 7. You can go right from BH to IGP FH WGSDPA BH WRITTEN EXAMINATION FOR FIRT-TIME HANDLERS No Yes It DepenDs on who you ask Thank you for taking this eXam. Begleithundprüfung (BH) EXAMINATION Host Club Name: Date: Name of Dog: Catalog #: Reg #: Tattoo/Chip: Birth Date: Handler Name: Breed: Result of the temperament test Pass/Fail A - BH Trial on Training Grounds or other open area Points Note 1 (On-lead heeling) 15 2 (Off-lead heeling) 15 3 (Sit exercise) 10 4 (Down with recall) 10 5 (Down under distraction) 10 (Total) 60 B - (Evaluation in traffic) 1 (Encounter with a group of people) 2 (Encounter with bicycle riders) 3 (Encounter with cars) 4 (Encounter with joggers and rollerbladers) 5 (Encounter with other dogs) 6 (Behavior of a dog that is tied up and left alone) EVALUATION Pass Fail WGSDPA JUDGES SHEET - IGP-1 Host Club Name: WGSDPA Date: Name of Dog: Catalog #: Reg #: Tattoo/Chip: Birth Date: Handler Name: Breed: TEMPERAMENT TEST: Pass or Fail? Pass or Fail? A -TRACKING PHASE A ) Tracklayer Name Time Track Laid ____Time Track Run__________________ ) Articles Indicated? Handler laid track of at least 300 paces long and aged 20 min. -

Avidog® Puppy Evaluation Test (APET)—Revised 5/2015

Avidog® Puppy Evaluation Test (APET)—Revised 5/2015 Avidog® Puppy Evaluation Test Helping Breeders Make the Best Match for Puppies and Owners Revised May 2015 Avidog® International, LLC www.Avidog.com Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Why Another Temperament Test? ...................................................................................................................... 4 A Little about the APET ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Who and What You Need for an APET ............................................................................................................... 10 When to Test ........................................................................................................................................................... 10 People and Roles ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Time ........................................................................................................................................................................ 13 Plan the Pups’ Meals .............................................................................................................................................. -

BOARD of DIRECTORS August 7-8, 2017 the Board Convened On

BOARD OF DIRECTORS August 7-8, 2017 The Board convened on Monday, August 7, 2017 at 8:00 a.m. All Directors were present. Also present was the Executive Secretary. The July 2017 Board minutes, copies of which were provided to all Directors, were discussed. Upon a motion by Dr. Davies, seconded by Mr. Menaker, the July 2017 minutes were approved unanimously, except for an abstention by Mr. Feeney because he was not in attendance at the July meeting. PRESIDENT’S REPORT Board Action Items Mr. Sprung reviewed Action Items, and reported on staff initiatives. There was discussion by the Board concerning reporting of efforts to increase registrations, entries and breeders as well as focus by staff to convert registerable dogs to registered dogs. There was debate about the impact of limited registration. It was the sense of the Board that limited registration was negatively impacting entries and registration totals. There was a motion by Mr. Wooding, seconded by Dr. Davies, and it was VOTED (unanimously), to instruct the Executive Secretary to send a memo to the Delegate Dog Show Rules Committee asking them to consider a rule change that would eliminate limited registration. Mr. Sprung agreed that the staff can provide parent clubs with statistics on litter, dog and limited registration for their respective breed. Fundraising Department Mr. Sprung introduced Robert Holcomb, AKC’s new Executive Director of Development. Mr. Holcomb gave an overview of his background in fundraising and his vision for how the new department would operate. Giving initiatives will be planned for all of AKC’s affiliates, which include, AKC Canine Health Foundation, AKC Reunite, AKC Humane Fund and the AKC Museum of the Dog as well as AKC. -

Which Personality Dimensions Do Puppy Tests Measure? a Systematic Procedure for Categorizing Behavioral Assays

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266320827 Which personality dimensions do puppy tests measure? A systematic procedure for categorizing behavioral assays ARTICLE in BEHAVIOURAL PROCESSES · SEPTEMBER 2014 Impact Factor: 1.57 · DOI: 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.09.029 READS 150 3 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: David L. Sinn Samuel D Gosling University of Tasmania University of Texas at Austin 26 PUBLICATIONS 781 CITATIONS 124 PUBLICATIONS 11,024 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: David L. Sinn letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 07 January 2016 Behavioural Processes 110 (2015) 117–124 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Behavioural Processes jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/behavproc Which personality dimensions do puppy tests measure? A systematic procedure for categorizing behavioral assays a,b a,c,∗ a Monica E. McGarrity , David L. Sinn , Samuel D. Gosling a University of Texas at Austin, Department of Psychology, 108 E. Dean Keeton Stop A8000, Austin, TX 78712-1043, USA b Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Rd., Austin TX 78744, USA c University of Tasmania, School of Biological Sciences, Private Bag 5, Hobart, TAS 7001, Australia a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: With the recent increase in interest in personality in dogs, behavioral assays of their behavior have Available online 30 September 2014 proliferated. There has been particularly strong interest in predicting adult behavior from puppy tests. -

Assessing Personality Traits in Dogs: Conceptual and Methodological Issues

Assessing personality traits in dogs: conceptual and methodological issues Evaluering av personalighestrekk hos hund: konseptuelle og metodiske aspekter Philosophiae Doctor (PhD) Thesis Conor Goold Norwegian University of Life Sciences Faculty of Biosciences Department of Animal and Aquacultural Sciences Ås 2017 Thesis number 2017:72 ISSN 1894-6402 ISBN 978-82-575-1468-6 Supervisors Prof. Ruth C. Newberry Department of Animal and Aquacultural Sciences Faculty of Biosciences Norwegian University of Life Sciences PO Box 5003, 1432 Ås Norway Dr. Judit Vas Department of Animal and Aquacultural Sciences Faculty of Biosciences Norwegian University of Life Sciences PO Box 5003, 1432 Ås Norway Prof. Bjarne O. Braastad Department of Animal and Aquacultural Sciences Faculty of Biosciences Norwegian University of Life Sciences PO Box 5003, 1432 Ås Norway i ii Acknowledgements Too many people have helped me through these last three years. I wrote and re-wrote this section a few times, but couldn’t do the acknowledgements justice on paper, so I’ll just keep it short and sweet. Firstly, my main supervisor Ruth is a superstar. Her support and encouragement throughout has been more than any PhD student or friend could wish for. Secondly, my co-supervisors Judit and Bjarne have been incredibly patient and supportive of my work and me as a student, happy for me to explore my ideas independently and be there to provide feedback whenever I needed it. Thirdly, to everyone else in the Ethology research group: thank you for being so welcoming and putting up with my terrible Norwegian (or considerable lack of) for so long. -

AMERICAN TEMPERAMENT TEST SOCIETY, INC. (ATTS) © 1994 PO Box 591279 ● Houston, TX 77259 ● (832) 982-2887

AMERICAN TEMPERAMENT TEST SOCIETY, INC. (ATTS) © 1994 PO Box 591279 ● Houston, TX 77259 ● (832) 982-2887 ATTS TESTER EXAMINATION THESE TEST QUESTIONS MAY NOT BE COPIED OR DISTRIBUTED NOTE: For all questions, select the best answer. A. MULTIPLE CHOICE – [52 Points] 1. The American Temperament Test Society, Inc. is: a. A private corporation b. A public corporation c. Not incorporated d. A not-for-profit corporation 2. ATTS was established to: a. Test all dogs for acquired temperament traits b. Provide for a uniform national program of temperament testing of purebred and mixed breed dogs c. Educate the general public on dog behavior d. Propose and encourage anti-vicious dog legislation 3. The ATTS motto is: a. All for one and one for all b. A sound mind in a sound body c. Good temperament is good, bad temperament is bad regardless of the breed d. Temperament is the sum total of all inborn and acquired physical and mental traits 4. ATTS is registered in the state of: a. California b. Missouri c. Delaware d. Florida 5. TT titles are awarded to: a. All dogs passing the temperament test b. All purebred dogs and spayed or neutered mixed breed dogs passing the temperament test c. All purebred dogs and spayed or neutered mixed breed dogs including spayed or neutered wolf- hybrids that pass the temperament test d. All spayed or neutered dogs that pass the temperament test 1 COPYRIGHT 1994, AMERICAN TEMPERAMENT TEST SOCIETY, INC. 6. The ATTS temperament test: a. Simulates a casual walk in a park or neighborhood b. -

Will Training Affect the Outcome? a Test-Retest Trial As a Forensic Tool

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária ASSESSING DOGS USING A TEMPERAMENT TEST – WILL TRAINING AFFECT THE OUTCOME? A TEST-RETEST TRIAL AS A FORENSIC TOOL SOPHIE LUISA FECHNER CONSTITUIÇÃO DO JÚRI: ORIENTADOR: Doutora Maria Manuela Grave Rodeia Espada Niza Doutor Gonçalo da Graça Pereira Doutora Ilda Maria Neto Gomes Rosa Doutor Gonçalo da Graça Pereira CO-ORIENTADOR: Doutora Anabela de Sousa Santos da Silva Moreira 2017 Lisboa UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária ASSESSING DOGS USING A TEMPERAMENT TEST – WILL TRAINING AFFECT THE OUTCOME? A TEST-RETEST TRIAL AS A FORENSIC TOOL SOPHIE LUISA FECHNER DISSERTAÇÃO DE MESTRADO INTEGRADO EM MEDICINA VETERINÁRIA CONSTITUIÇÃO DO JÚRI: ORIENTADOR: Doutora Maria Manuela Grave Rodeia Espada Niza Doutor Gonçalo da Graça Pereira Doutora Ilda Maria Neto Gomes Rosa Doutor Gonçalo da Graça Pereira CO-ORIENTADOR: Doutora Anabela de Sousa Santos da Silva Moreira 2017 Acknowledgements I would like to start off telling you about an incident that happened to me on one of my frequent dog-crowded walks across the Alentejo countryside. It was a lovely afternoon until one of my Pit Bull bitches (who was having a particularly “bitchy” day) had a minor but majorly noisy physical disagreement with one of the dogs belonging to our neighbor, a cattle herder. I went in the melée with all the stress of a Pit Bull owner who cannot put one wrong foot on the line, much less have a dog exhibiting anything less than super- social behaviour, and positively fell apart in apologies and high-strung offers of help and veterinary care. Of course the other dog was fine, it was one of those squabbles with a lot of drool and no blood, and the cattle herder, who had not even let go of his staff, drawled in the untranslatable Alentejo accent: “Oh menina.. -

Fighting Nature: an Analysis and Critique of Breed-Specific Flourishing Arguments for Dog Fights

society & animals (2015) 1-19 brill.com/soan Fighting Nature: An Analysis and Critique of Breed-Specific Flourishing Arguments for Dog Fights Ian Werkheiser Department of Philosophy, University of Texas, Rio Grande Valley [email protected] Abstract Social science literature on dog fighting illustrates an important element in the dis- course of dog fighters, namely patriarchy. However, it has not addressed another com- mon element, namely flourishing. According to this element of that discourse, some dog breeds are born to fight, and therefore dog fighters are helping them achieve their best lives. This argument is explicitly made by dog fighters, and it is inadvertently supported by those trying to give other dogs breed-specific flourishing, and those who advocate for breed-specific legislation. This poses a problem for advocates of using flourishing to understand animal welfare, particularly if they use kinds (like species and breed) to determine what counts as a flourishing life for a particular nonhuman animal. I argue that we can keep a slightly weakened version of breed-specific flourishing as a start- ing place for understanding individual dogs without endorsing sport fighting or breed- specific legislation for “vicious” breeds of dogs. Keywords dog fighting – flourishing – animal welfare – animal ethics – breed-specific legislation Flourishing, as opposed to a welfarist or more traditional rights-based approach, is a growing part of the discourse on nonhuman animal ethics. This is particularly true as an extension of the capabilities approach, largely begun by Nussbaum (2001, 2004, 2006) and taken up by other authors, both within and outside of the dominant capabilities approach (e.g., Bynum, 2006; Walker, © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2�15 | doi 10.1163/15685306-12341375 2 doi 10.1163/15685306-12341375 | Werkheiser 2007; White, 2007; Donaldson & Kymlicka, 2011). -

Early Experiences, Maternal Care and Behavioural Test Design

Linköping Studies in Science and Technology Dissertation No. 1703 Early Experiences, Maternal Care and Behavioural Test Design Effects on the Temperament of Military Working Dogs Pernilla Foyer IFM Biology Division of Zoology AVIAN Behavioural Genomics and Physiology Group Linköping University, SE-591 83 Linköping, Sweden Linköping 2015 Early Experiences, Maternal Care and Behavioural Test Design Effects on the Temperament of Military Working Dogs Linköping Studies in Science and Technology Dissertation No. 1703 ISBN 987-91-7685-945-2 ISSN 0345-7524 Front and back cover: German Shepherd pup Photo: Åsa Vilsson Copyright © Pernilla Foyer unless otherwise noted Printed by LiU-Tryck, Linköping, Sweden, 2015 ”A dog´s got personality and personality goes a long way.” Jules Winnfield, from the movie Pulp Fiction ABSTRACT Domestication has resulted in animals with broad variations between as well as within breeds, which allows for the selection and breeding of animals for preferred traits. This selection has affected both the genotypes and phenotypes of animals. In dogs, it has allowed for breeding for different purposes, such as companionship or the performance of specific tasks, e.g., herding, hunting, searching and protecting. Each of these types of working dogs has specific traits that are, in part, controlled by genes; however, genes are not solely responsible for the variations in the traits of an individual. The environment also plays a role, which has been studied in rodents and primates in recent decades. For instance, it has been shown that the amount of maternal care that a rat receives as a pup affects its temperament later in life; the more maternal care, i.e., licking, grooming and arched-back nursing (LG-ABN) that a rat receives, the more stress resistant, less reactive and more explorative it will be as an adult.