Iwo Jima's Jack Lucas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Studies in Quality Manufacturing

PQM201B Student Book Case Studies In Quality Manufacturing Given case study examples of PQM processes with troublesome outcomes, evaluate facets of existing QMS elements. Relate discussed PQM topic areas to each case and identify opportunities to apply them. • What failures of the system’s quality management system are evident? • Was the failure (A) Design related, (B) Workmanship related, (C) Material related, or (D) a combination? • What processes / components were Key to the item? Critical to the item? • What corrective actions (if any) were incorporated as a result of the situation? • How might the following PQM topic areas apply: • Integrated Manufacturing Planning • Continuous Process Improvement • Lean Manufacturing Teams consider their assigned case with these questions in mind. You are encouraged to consider other references and/or information when exploring these cases. Your team will be provided a discussion period after the lecture portion of the Quality Management lesson to share your impressions about your assigned case amongst yourselves. Each team will then present a summary of your findings to your classmates to conclude the lesson. v16.2 195 PQM201B Student Book v16.2 196 PQM201B Student Book The Loss of the USS THRESHER On April 10, 1963, the nuclear submarine USS THRESHER failed to surface from a test dive and was lost at sea. On the morning of April 10, the THRESHER proceeded to conduct sea trials about 200 miles off the coast of Cape Cod, MA. At 9:13am, the USS SKYLARK received a signal indicating that the submarine was experiencing “minor difficulties.” Shortly afterward, the SKYLARK received a series of garbled, undecipherable message fragments from the THRESHER. -

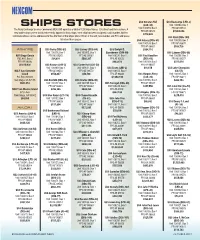

NEXCOM Ships Stores Sales Chart Had No Sales Listed for Fiscal 2018

NEXCOM USS Gunston Hall USS Kearsarge (LHD-3) SHIPS STORES (LSD-44) Unit 100284, Box 1 The Navy Exchange Service Command (NEXCOM) operates a total of 129 Ships Stores: 126 afloat and three ashore. A Unit 100259, Box 1 FPO AE 09534 FPO AE 09573 $7,064,096 new addressing system instituted recently applies to Navy ships; each ship has been assigned a unit number. Written $719,503 communications can be addressed to the attention of the Ships Store Officer at the unit, box number and FPO addresses USS Kidd (DDG-100) listed on these pages. USS Halsey (DDG-97) Unit 100209, Box 1 Unit 100139, Box 1 FPO AP 96670 FPO AP 96667 $106,726 ASHORE USS Barry (DDG-52) USS Carney (DDG-64) USS Dwight D. $304,110 Unit 100278, Box 1 Unit 100302, Box 1 Eisenhower (CVN-69) USS Laboon (DDG-58) NSF Diego Garcia FPO AE 09565 FPO AE 09583 Unit 100236, Box 1 USS Paul Hamilton Unit 100296, Box 1 PSC 466, Box 2 $24,816 $580,307 FPO AE 09532 (DDG-60) FPO AE 09577 FPO AP 96595 $983,472 Unit 100169, Box 1 $511,014 $6,610,436 USS Bataan (LHD-5) USS Carter Hall (LSD-50) FPO AP 96667 Unit 100309, Box 1 Unit 100121, Box 1 USS Essex (LHD-2) $91,678 USS Lake Champlain NALF San Clemente FPO AE 09554 FPO AE 09573 Unit 100150, Box 1 (CG-57) Island $158,847 $50,786 FPO AP 96643 USS Harpers Ferry Unit 100135, Box 1 P.O. Box 357033 $1,560,199 (LSD-49) FPO AP 96671 San Diego, CA 92135 USS Benfold (DDG-65) USS Chafee (DDG-90) Unit 100165, Box 1 $282,753 $603,253 Unit 100177, Box 1 Unit 100199, Box 1 USS Farragut (DDG-99) FPO AP 96665 FPO AP 96661 FPO AP 96662 Unit 100239, Box 1 $147,558 USS Lake Erie (CG-70) NOLF San Nicolas Island $295,345 $409,355 FPO AA 34091 Unit 100155, Box 1 575 I-Ave. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

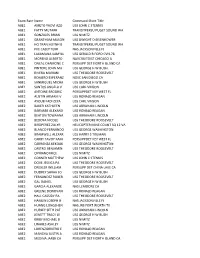

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE -

Home Hawaiian Raptors

What’s INSIDE DBIDS to be implemented O’Kane brings hoops Joint Base to celebrate Magic show coming to at JBPHH this month championship back to Earth Day at Hickam Sharkey Theater > A-3 ship Harbor >B-4 > B1 >B-3 April 15, 2016 www.cnic.navy.mil/hawaii www.hookelenews.com Volume 7 Issue 14 Welcome home Hawaiian Raptors Story and photos by Fighter Squadron, supported area of responsibility encom- coalition forces and conducted September Tech. Sgt. Aaron Oelrich by the Hawaii Air National passes the Southwest Asia our operations flawlessly,” 2015. Guard’s 154th Maintenance and most of the Middle East. said one of the pilots from the 15th Wing Public Affairs Squadron and the active duty The Hawaiian Raptors were Hawaii Air National Guard. 15th Maintenance Squadron. an integral part of Operation The F-22 fighter aircraft Editor’s note: Because of se- The deployment to the Inherent Resolve. and the Airmen of the Hawai- curity considerations and host Central Command area of re- “Our Airmen performed ex- ian Raptors started this nation sensitivities, the Ha- sponsibility marked the first tremely well and they did it mission by departing waii Air National Guard will operational deployment for with the Aloha spirit. Mainte- from Joint Base not release the names of its the Hawaiian Raptors. The nance did an outstanding job, Pearl Harbor- personnel who deployed, and Cen- tral Command and met all their tasks. We in- Hickam the country, or base where the tegrated well with the other in late Raptors operated. Friends and family cele- brate the homecoming of their loved ones as they returned to Joint Base Pearl Har- bor-Hickam, April 8. -

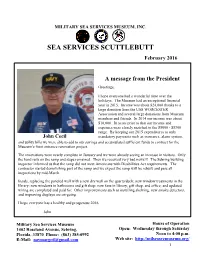

SEA SERVICES SCUTTLEBUTT February 2016

MILITARY SEA SERVICES MUSEUM, INC. SEA SERVICES SCUTTLEBUTT February 2016 A message from the President Greetings, I hope everyone had a wonderful time over the holidays. The Museum had an exceptional financial year in 2015. Income was about $24,000 thanks to a large donation from the USS WORCESTER Association and several large donations from Museum members and friends. In 2014 our income was about $10,000. In years prior to that our income and expenses were closely matched in the $5000 - $8300 range. By keeping our 2015 expenditures to only John Cecil mandatory payments such as insurance, alarm system, and utility bills we were able to add to our savings and accumulated sufficient funds to contract for the Museum’s front entrance renovation project. The renovations were nearly complete in January and we were already seeing an increase in visitors. Only the hand rails on the ramp and steps remained. Then we received very bad news!!! The Sebring building inspector informed us that the ramp did not meet Americans with Disabilities Act requirements. The contractor started demolishing part of the ramp and we expect the ramp will be rebuilt and pass all inspections by mid-March. Inside, replacing the paneled wall with a new dry wall on the quarterdeck; new window treatments in the library; new windows in bathrooms and gift shop; new fans in library, gift shop, and office; and updated wiring are completed and paid for. Other improvements such as installing shelving, new smoke detectors, and improving displays are on-going. I hope everyone has a healthy and prosperous 2016. -

Island Blood the Stories of Samoan Vietnam War Veterans

ISLAND BROTHERS/ ISLAND BLOOD THE STORIES OF SAMOAN VIETNAM WAR VETERANS A portfolio project submitted to the Graduate Division of the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES April 2012 By Peter L. Akuna Sr. Committee Members Tarcisius T. Kabutaulaka (Chairperson) Julie Walsh Lola Quan Bautista This Project is dedicated to: Cpl. Lane Fatutoa Levi of Fagatogo, American Samoa SP4 Fiatele Taulago Teo of Pago Pago, American Samoa LCPL. Fagatoele, Lokeni of Mapusaga, American Samoa PFC. Benjamin Galu Willis of Leone, American Samoa Whose names are engraved on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall at Arlington, Virginia And to my Pacific Islands brothers and sisters of American Samoa who had served in the Vietnam War 2 Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to the Vietnam Veterans of Samoa who shared their stories with me. It took a lot of courage for them to open their heart and souls and reveal their personal stories and relive horrifying memories of a war that they would rather leave behind in the abyss of their memories. By telling their stories, they have assisted in my endeavor to make known to the world the sacrifices of Pacific Islanders in the United States military. Here, the stories are about Pacific Islanders, more specifically Samoans in the Vietnam War. I thank each and every one of them. Their heartfelt cooperation exceeded my expectations. I also am grateful to Dr. Terence Wesley-Smith, the Director of the Center for Pacific Islands Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, and chair of the Center’s graduate program and members of the graduate committee for accepting me into their program. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

Approach Sep-Oct04 Covers.Indd

The Naval Safety Center’s Aviation Magazine September-October 2004 Volume 49 No. 5 Features RADM Dick Brooks Commander, Naval Safety Center Col. Alan Lewis, USMC Deputy Commander John Mahoney Head, Communications and Marketing Naval Safety Center (757) 444-3520 (DSN 564) Dial the following 4 Bird on a Wire—Almost extensions any time during the greeting By LCdr. Mike Beidler Publications Fax (757) 444-6791 A helo training-command story that should hit home with Approach Staff all helo drivers. Jack Stewart Editor [email protected] Ext. 7257 Allan Amen Graphics, Design & Layout [email protected] Ext. 7248 7 Taking a Dip Ginger Rives Distribution (Magazines and Posters) By Lt. Josh Potocko [email protected] Ext. 7256 Viking crew almost gets wet when they think they can Col. Alan Lewis, USMC Aviation Safety Programs “handle it.” [email protected] Ext. 7225 Cdr. Deke Forbes Aircraft Operations Division [email protected] Ext. 7203 Cdr. Chuck Huff Aircraft Mishap Investigation Division 10 Blowing Sand in the Arabian Gulf [email protected] Ext. 7236 By LCdr. Mike Saling Capt. Nicholas Webster Aeromedical Division [email protected] Ext. 7228 The changing weather in the Arabian Gulf almost turns a successful cruise into disaster. Analysts Cdr. Deke Forbes NATOPS/WESS [email protected] Ext. 7203 Cdr. Mike Scavone Carrier Branch Head, EA-6B, S-3, T-45 , F-14 [email protected] Ext. 7272 Live Strong, Ride Safely Cdr. “Skel” Barrickman E-2, C-2 20 [email protected] Ext. 7212 By LCdr. -

AH200710.Pdf

◀ AD3 Eric Kern observes an aircraft descending from the flight deck to the hangar bay on an aircraft elevator aboard USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76). Photo by MC3 Kevin S. O’Brien [On the Front Cover] Sailors aboard USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) hroughout the year, All Hands tries to showcase the stand at attention as two military veterans are laid to rest in the Pacific Ocean during a burial-at- many ways that Sailors around the globe contribute sea ceremony. ADCS Gilberto Gordils Jr., formerly assigned to Strike Fighter Squadron 115, was one to the well-being of their nation. of the veterans laid to rest during the ceremony. Gordils’ former squadron is currently aboard Ronald T Reagan assigned to Carrier Air Wing 14 where many of the Sailors from the squadron gathered to pay You’ll find Sailors just about anywhere, supporting maritime security, fostering international their last respects. cooperation, providing humanitarian assistance, contributing boots on the ground and participating in a Photo by MC3 Joanna M. Rippee huge range of missions. You’ll find evidence of that right here in our annual “Any Day in the Navy” issue, [On the Back Cover] which is intended to highlight the Navy as seen by Navy photographers and others around the world. We Sailors assigned to USS Hawaii (SSN 776) stand at attention after hoisting the National Ensign and here on the staff of All Hands can’t be everywhere at once, but they are. Commissioning Pennant, placing the ship in active service. Hawaii is the third Virginia-class submarine It’s a challenge to take more than 12,000 photos taken between July 2006 and July 2007, and distill to be commissioned, and the first major U.S. -

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 ADORNO KELONA K

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 ADORNO KELONA K USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE1 ALVAREZ JESUS O USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 AUSTIN NICOLE G USS RONALD REAGAN ABE1 BAIRD TREVORNE NAVMEDCEN PORTSMOUTH VA ABE1 BODE MITCHELL D USS NIMITZ ABE1 BOUDREAUX ANGEL PERSUPP DET WILLOW GROVE PA ABE1 BROWN TEVON LAM USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 BURUM KAYLAH DO USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 COLE CHAD AKEEM NAVCRUITDIST SAN FRANCISCO CA/ ABE1 DANIELS TYVON NAVSUPPACT LAKEHURST NJ ABE1 DELEON FRED IVA NAVCRUITDIST SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 DEPUGH CALVIN E USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 DIAMOND TYLER J USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 HARRIS MICHAEL USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 HERNANDEZ JOHNM PERSUPP DET BANGOR WA ABE1 LOWRY JOHN AARO USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE1 MARTIN STEVEN E NAS OCEANA VA ABE1 MATHEWS GEOFFRE COMNAVREG SW SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 MEDINANIETO WIL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 ODONNELL KIMBER USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 ROQUEPEREZ ROBE USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 SANDERS JAMICHA USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 SCIOR ZACKARY M NAS OCEANA VA ABE1 SHAW GEORGE KEA USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 WOODRUFF DUSTIN USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE2 ANSEL TYLER AND NAVSTA MAYPORT FL ABE2 ARNOLD CHRISTOP NAVSUP FLTLOG CTR JACKSONVILLE ABE2 BAKER JAZIMEN M NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 BARELA HAILEY S USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BARKER PAUL GAR USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 BENJAMIN ERIC M USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 BROWN ARIEL MOT NAVSUPPACT LAKEHURST NJ ABE2 CARDOZOZENTENO NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE2 DEFEO JOHN MICH USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 EDGERTON MIRAND PERSUPP DET BANGOR WA ABE2 FACTOR FORREST PERSUPP DET -

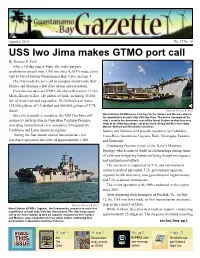

USS Iwo Jima Makes GTMO Port Call by Terence R

August 6, 2010 Vol. 67 No. 30 USS Iwo Jima makes GTMO port call By Terence R. Peck After a 10-day stop in Haiti, the multi-purpose amphibious assault ship, USS Iwo Jima (LHD7) made a port visit to Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba on Aug. 4 The ship made the port call to resupply and provide their Sailors and Marines a few days of rest and relaxation. Over the two days at GTMO, the ship will receive 11,520 Meals-Ready-to-Eat, 140 pallets of food, including 35,000 lbs. of fresh fruit and vegetables; 30,240 bottles of water; 115,000 gallons of J-5 jet fuel and 800,000 gallons of F-76 diesel. Photo by Terence R. Peck Once the resupply is complete, the USS Iwo Jima will Naval Station GTMO buses stand by for the Sailors and Marines aboard the amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima. The buses transported the resume its participation in Operation Continue Promise, ship’s crew to the downtown area of the Naval Station so that they may shop at the Navy Exchange, eat at the local dining facilities and enjoy providing humanitarian civic assistance throughout the Morale, Welfare and Recreation activities. Caribbean and Latin American regions. Sailors and Marines will provide assistance to Colombia, During the four-month annual humanitarian civic Costa Rica, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Nicaragua, Panama assistance operation, the crew of approximately 1,600 and Suriname. Continuing Promise is part of the Navy’s Maritime Strategy, which seeks to build on relationships during times of calm and mitigating human suffering though interagency and multinational efforts.