Government Intervention in Emerging Networked Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM 12 CFR Part 229 Regulation CC

FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM 12 CFR Part 229 Regulation CC [Docket No. R-1637] RIN 7100-AF 28 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION 12 CFR Part 1030 [Docket No. CFPB–2018–0035] RIN 3170–AA31 Availability of Funds and Collection of Checks (Regulation CC) AGENCY: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Board) and Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (Bureau) ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: The Board and the Bureau (Agencies) are amending Regulation CC, which implements the Expedited Funds Availability Act (EFA Act), to implement a statutory requirement in the EFA Act to adjust the dollar amounts under the EFA Act for inflation. The Agencies are also amending Regulation CC to incorporate the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (EGRRCPA) amendments to the EFA Act, which include extending coverage to American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and Guam, and making certain other technical amendments. DATES: This rule is effective July 1, 2020, except for the amendments to §§ 12 CFR 229.2(c), (ff), and (jj), 229.12(e), 229.43, and 12 CFR Part 1030 which are effective [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Board: Gavin L. Smith, Senior Counsel (202) 452-3474, Legal Division, or Ian C.B. Spear, Manager (202) 452-3959, Division of Reserve Bank Operations and Payment Systems. Bureau: Joseph Baressi and Marta Tanenhaus, Senior Counsels, Office of Regulations, at (202) 435-7700. If you require this document in an alternative electronic format, please contact [email protected]. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: I. -

Interpretive Letter #1036 August 2005 12 USC 36

O Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks Washington, DC 20219 August 10, 2005 Interpretive Letter #1036 August 2005 12 USC 36 Subject: Remote Deposit Capture Terminals Dear [ ]: This is in response to your letter of June 2, 2005 on behalf of [ National Bank ], requesting confirmation of our earlier telephone discussion as to whether a check scanning terminal at a nonbank location, used by a bank customer to transmit electronic images of checks to the bank for deposit, is a branch within the meaning of the McFadden Act, 12 U.S.C. § 36. This will confirm my opinion expressed during that call that such terminals are not branches under federal law regardless of whether they are owned by the customer or the bank. Facts According to your letter, it is now possible for a corporate customer of a bank to use a check scanning terminal, located on the customer’s premises, to make deposits. The customer scans a check and an electronic image of the check is then transmitted to the bank to effect a deposit. This can be done even when the depositary bank is located in another state and does not have a branch in the customer’s state. In some cases the scanning terminal may be owned by the bank, while in other cases the customer or a third party may own the terminal. This process, known as “remote deposit capture,”1 has been made possible by the Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act (“Check 21 Act”),2 which was enacted in 2003 and took effect on October 28, 2004. -

Regulation CC

Consumer Affairs Laws and Regulations Regulation CC Introduction The Expedited Funds Availability Act (EFA) was enacted in August 1987 and became effective in Septem- ber 1988. The Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act (Check 21) was enacted October 28, 2003 with an effective date of October 28, 2004. Regulation CC (12 C.F.R. Part 229) issued by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System implements the EFA act in Subparts A through C and Check 21 in Subpart D. Regulation CC sets forth the requirements that depository institutions make funds deposited into transaction accounts available according to specified time schedules and that they disclose their funds availability poli- cies to their customers. The regulation also establishes rules designed to speed the collection and return of unpaid checks. The Check 21 section of the regulation describes requirements that affect banks that create or receive substitute checks, including consumer disclosures and expedited recredit procedures. Regulation CC contains four subparts: • Subpart A – Defines terms and provides for administrative enforcement. • Subpart B – Specifies availability schedules or time frames within which banks must make funds avail- able for withdrawal. It also includes rules regarding exceptions to the schedules, disclosure of funds availability policies, and payment of interest. • Subpart C – Sets forth rules concerning the expeditious return of checks, the responsibilities of paying and returning banks, authorization of direct returns, notification of nonpayment of large-dollar returns by the paying bank, check-indorsement standards, and other related changes to the check collection system. • Subpart D – Contains provisions concerning requirements a substitute check must meet to be the legal equivalent of an original check; bank duties, warranties, and indemnities associated with substitute checks; expedited recredit procedures for consumers and banks; and consumer disclosures regarding sub- stitute checks. -

Download This Article

The Fidelity Law Journal published by The Fidelity Law Association Volume XIII, October 2007 Cite as XIII Fid. L.J. ___ (2007) WWW.FIDELITYLAW.ORG The Fidelity Law Journal is published annually. Additional copies may be purchased by writing to: The Fidelity Law Association, c/o Wolff & Samson PC, One Boland Drive, West Orange, New Jersey 07052. The opinions and views expressed in the articles in this Journal are solely of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Fidelity Law Association or its members, nor of the authors’ firms or companies. Publication should not be deemed an endorsement by the Fidelity Law Association or its members, or the authors’ firms or companies, of any views or positions contained herein. The articles herein are for general informational purposes only. None of the information in the articles constitutes legal advice, nor is it intended to create any attorney-client relationship between the reader and any of the authors. The reader should not act or rely upon the information in this Journal concerning the meaning, interpretation, or effect of any particular contractual language or the resolution of any particular demand, claim, or suit without seeking the advice of your own attorney. The information in this Journal does not amend, or otherwise affect, the terms, conditions or coverages of any insurance policy or bond issued by any of the authors’ companies or any other insurance company. The information in this Journal is not a representation that coverage does or does not exist for any particular claim or loss under any such policy or bond. -

Report to the Congress on the Check Clearing for the 21St Century Act of 2003

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Report to the Congress on the Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act of 2003 April 2007 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Report to the Congress on the Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act of 2003 Submitted to the Congress pursuant to section 16 of the Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act of 2003 April 2007 Report to the Congress on Check 21 Contents Contents I. Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 1 II. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4 III. Background ................................................................................................................. 6 Overview of Check 21................................................................................................. 6 Overview of the EFAA................................................................................................ 7 IV. Check 21 Adoption.................................................................................................... 10 V. Funds-availability Practices ...................................................................................... 13 VI. Returned Checks........................................................................................................ 15 VII. Check Losses............................................................................................................ -

BST TOC (Page 1)

BS&T’S EXECUTIVE SUMMIT 2011: SEE PAGES 20-21 NEW STRATEGIES FOR NEW BUSINESS MODELS Business Innovation Powered By Technology July 2011 Arkadi Pete Kuhlmann Kight Muhammed Steve Yunus Jobs Richard Jack Fairbank Dorsey INNOVATORS OF THE DECADE Who has had the most significant impact on banking technology over the past 10 years? Here are 10 innovators who have helped shape the 21st century banking industry. p.15 David Jeff Walker Bezos Aaron Barney Patzer Frank $8.95 www.banktech.com B:8.375” S:7” Visit star.com/learnmore B:11.125” S:9.4375” In today’s changing debit landscape, choose the STAR® Network to ensure success every step of the way. Regulatory change is coming, and you need to prepare. The STAR® Network adds value beyond the transaction with: • Cutting-edge Security Solutions • Industry-leading Innovation • Coast-to-coast POS/ATM Access • Proven Commitment ©2011 First Data Corporation. All Rights Reserved. 79649_Star_Mag_FP_Size_A.indd 215 Park Av. South, Saved At: 4-11-2011 2:55 PM By: JPavia / mgobel Printed at: None Print #: 1 Round #: 1 2nd Level NY, NY, 10003 212.206.1005 Job Info Specs Fonts, Images & Inks Approvals W/C OK Client: FD Bleed: None Inks: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black Creative Director: Product: First Data Trim: 8.375” x 11.125” Fonts: Simple Sans (Regular, Medium) Art Director: Job #: 79649 Safety: 7” x 9.4375” Images: grey_bg_7x5.tif (Gray; 354 ppi; 169.15%), Copywriter: Star_Logo.eps, FD_3C_4c.eps, FD_Star.eps, FD_Bird.eps, Job Title: Star Program Ads Gutter: None Account: FD_Cloud2.eps, FD_Cloud1.eps, FD_Hat.eps, FD_Man.eps, FD-Beyond-Symbol-4c_ERS.eps, FD-Tagline-4c_ERS.eps Studio: Publications: The Warren Group, Bank News, Bank System & Tech Print Production: Business Innovation Powered By Technology July 2011 banktech.com INNOVATORS OF THE DECADE COVER STORY FEATURE STORY 29 How to Build a 15 Unstoppable Force Secure Mobile App THE INNOVATION JUGGERNAUT Innovation — and the change As banks rush to deploy mobile that comes with it — are inevitable. -

RESERVE BANK of INDIA- CHEQUE TRUNCATION PROCESS Cheque Truncation - Pilot Implementation

INTRODUCTION Cheque Truncation is a process in which the image of the relevant data of a cheque is electronically captured and transmitted to enable payment of that cheque to the payee's account and simultaneously debiting the account of the drawer without the physical movement of the cheque itself. Payment systems and payment services play a key role in the efficient functioning of the financial system within a country. The payment system needs to ensure that financial transactions are settled in a timely manner and complimented with reliability and security, which is vital to the maintenance of market confidence and to the safe and sound functioning of financial market. Even though there are various cashless payment instruments in the country, cash still exists as the most popular retail payment due to convenience in settling small value transactions and ready acceptance to the legal tender for payment of any amount in any part of the country. Cheques are mainly used for retail payments. More than 90 percent of the total value of cashless retail payments is done through cheques. This statistic alone highlights the importance of cheque-based transactions in the national payment system. To reduce the time taken in clearing and settlement of cheques, and to avoid physical transportation of cheques, and to enhance the reliability and the security of the retail payment system, cheque truncation/ imaging technology is introduced. Cheque Truncation System (CTS) is an image-based cheque clearing system, which replaces the physical cheque flow with electronic information flow throughout clearing cycle. This process eliminates the actual cheque movement involved in clearing and hence reduces the delays associated with the movement of cheques. -

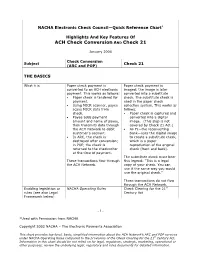

ACH Check Conversion and Check 21

NACHA Electronic Check Council—Quick Reference Chart* Highlights And Key Features Of ACH Check Conversion AND Check 21 January 2004 Check Conversion Subject Check 21 (ARC and POP) THE BASICS What it is Paper check payment is Paper check payment is converted to an ACH electronic imaged; the image is later payment. This works as follows: converted into a substitute • Paper check is tendered for check. The substitute check is payment. used in the paper check • Using MICR scanner, payee collection system. This works as scans MICR data from follows: check. • Paper check is captured and • Payee adds payment converted into a digital amount and name of payee, image. (This step is not then transmits data through covered by Check 21 Act.) the ACH Network to debit • An FI—the reconverting customer’s account. bank—uses the digital image • In ARC, the check is to create a substitute check, destroyed after conversion; which is a paper in POP, the check is reproduction of the original returned to the checkwriter check (front and back). at the time of payment. The substitute check must bear These transactions flow through this legend: “This is a legal the ACH Network. copy of your check. You can use it the same way you would use the original check.” These transactions do not flow through the ACH Network. Enabling legislation or NACHA Operating Rules Check Clearing for the 21st rules (see also Legal Century Act Framework below) - 1 - *Used with Permission from NACHA Copyright 2003 NACHA – The Electronic Payments Association This chart provides top-level, basic, simplified information about the ACH Network’s ARC and POP services under NACHA Operating Rules compared to the provisions of the Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act. -

GAO-09-8 Check 21 Act: Most Consumers Have Accepted And

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees GAO October 2008 CHECK 21 ACT Most Consumers Have Accepted and Banks Are Progressing Toward Full Adoption of Check Truncation GAO-09-8 October 2008 CHECK 21 ACT Accountability Integrity Reliability Consumers Have Accepted and Banks Are Highlights Progressing Toward Full Adoption of Check Highlights of GAO-09-8, a report to Truncation Congressional Committees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Although check volume has Check truncation has not yet resulted in overall gains in economic efficiency declined, checks still represent a for the Federal Reserve or for a sample of banks while Federal Reserve and significant volume of payments that bank officials expect efficiencies in the future. GAO’s analysis of the Federal need to be processed, cleared, and Reserve’s cost accounting data suggests that its costs for check clearing may settled. The Check Clearing for the have increased since Check 21, which may reflect that the Federal Reserve 21st Century Act of 2003 (Check 21) was intended to make check must still process paper checks while it invests in equipment and software for collection more efficient and less electronic processing and incurs costs associated with closing a number of costly by facilitating wider use of check offices. However, GAO found that the Federal Reserve’s work hours electronic check processing. It and transportation costs associated with check services declined from the authorized a new legal fourth quarter of 2001 through the fourth quarter of 2007. Several of the 10 instrument—the substitute check— largest U.S. -

Mastercard Pushes IPO to Zations That Spent Better Than $1 Billion Last Year Alone on Check Imag- Second Quarter of 2006

March 13, 2006 • Issue 06:03:01 Inside this issue: News Check image Industry Update .....................................14 Off to a great start: GS Online exchange inches has 3.3 million hits in January ..............38 its way to POS Congressional questions on interchange ...58 Waffl e House to accept new report predicts that 2006 will be the year check image exchange credit cards – fi nally ............................ 62 enters the mainstream. That's good news for banks and other organi- MasterCard pushes IPO to zations that spent better than $1 billion last year alone on check imag- second quarter of 2006 ......................74 ing technologies. Check 21 spurs POS, A Related stories back offi ce interest .............................. 68 It's apt to take a few more Card security breaches across years, however, for the Check 21: An evolution, not a revolution .......... 67 the country may be linked .................... 94 momentum behind check Check 21 spurs POS, back office interest .......... 68 Discover to drop 'no surcharge' ban ........ 96 image exchange to reach Features the merchant community (see "Check 21 spurs POS, back office interest" on AgenTalkSM: Mike Rottkamp page 68). Experience goes a long way ................22 ATMIA East: Big on security The report, "Check Image Exchange: Roads to Rome," authored by C By Tracy Kitten, ATMmarketplace.com ..... 30 elent LLC Analyst Alenka Grealish, predicts that by the end of 2006, 18% of inter-bank check clearing in America will be done electronically, end to end. Views That's a significant increase in adoption, considering no more than 5% of t Check 21: An evolution, hese checks (known as transit items) were cleared as end-to-end electronic not a revolution items last year. -

Person-To-Person Electronic Funds Transfers: Recent Developments and Policy Issues

No. 10-1 Person-to-Person Electronic Funds Transfers: Recent Developments and Policy Issues Oz Shy Abstract: The paper investigates the reasons why person-to-person electronic funds transfers are still not very common in the United States compared with practices in many other countries. The paper also describes recent enhancements to online and mobile banking that provide account holders with low-cost interfaces to manage person-to-person electronic funds transfers via automated clearing house (ACH). On the theoretical side, the paper characterizes the critical mass levels needed for payment instruments to become widely adopted. Given the Fed's long-term heavy involvement in check clearing, the paper concludes with policy discussions of whether intervention is needed. Keywords: Automated clearing houses (ACH); Person-to-person Electronic Funds Transfers; Account-to-account transfers; Online Banking; Mobile banking. JEL Classifications: E42, G29, D14 Oz Shy is a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and a member of the Consumer Payments Research Center in the research department. I thank Terri Bradford, Sean Carter, Dickson Chu, Paul Connolly, Marianne Crowe, Jean Fisher, Charles Fletcher, Fumiko Hayashi, Ben Levinger, Suzanne Lorant, Richard Oliver, Scott Schuh, Joanna Stavins, Bob Triest, Marianne Verdier, Mike Zabek, and Jeff Zhang for all their help and guidance. This paper, which may be revised, is available on the web site of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston at http://www.bos.frb.org/economic/ppdp/index.htm. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. -

Rules & Regulations 2009

1 2 COPYRIGHT “Remote Deposit Capture Rules & Training Guide 2013©” is published and printed in the USA and marketed worldwide. Copyright © 2013 by T. Houston Technology Group. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any informational storage or retrieval system without written permission from the publisher, except for brief quotations used in critical articles and reviews. For information contact: T. Houston Technology Group, P.O. Box 1727, Alvin, Texas 77512. Telephone (281) 756-0409 or email: [email protected]. For additional project team copies or corporate subscriptions, contact the above numbers, but do not make any additional copies of the book or pages. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Most people work under the most difficult of circumstances: stress, fear, joy, deadlines, and unreasonable customer demands. We struggle to find balance in our lives. In the Old Testament, a simple shepherd named David had the same problems on his way to becoming the "greatest king of Israel." During his turbulent life, he paused occasionally to write advice about how to handle day-to-day problems. Although these Psalms are thousands of years old, they still bring peace and hope to all that read and believe them. 23 Psalms (King James Translation): The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters. He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name's sake. Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.