A Transcript of the Book Review Podcast from Aug. 2, 2019. Carl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Filibuster and Reconciliation: the Future of Majoritarian Lawmaking in the U.S

The Filibuster and Reconciliation: The Future of Majoritarian Lawmaking in the U.S. Senate Tonja Jacobi†* & Jeff VanDam** “If this precedent is pushed to its logical conclusion, I suspect there will come a day when all legislation will be done through reconciliation.” — Senator Tom Daschle, on the prospect of using budget reconciliation procedures to pass tax cuts in 19961 Passing legislation in the United States Senate has become a de facto super-majoritarian undertaking, due to the gradual institutionalization of the filibuster — the practice of unending debate in the Senate. The filibuster is responsible for stymieing many legislative policies, and was the cause of decades of delay in the development of civil rights protection. Attempts at reforming the filibuster have only exacerbated the problem. However, reconciliation, a once obscure budgetary procedure, has created a mechanism of avoiding filibusters. Consequently, reconciliation is one of the primary means by which significant controversial legislation has been passed in recent years — including the Bush tax cuts and much of Obamacare. This has led to minoritarian attempts to reform reconciliation, particularly through the Byrd Rule, as well as constitutional challenges to proposed filibuster reforms. We argue that the success of the various mechanisms of constraining either the filibuster or reconciliation will rest not with interpretation by † Copyright © 2013 Tonja Jacobi and Jeff VanDam. * Professor of Law, Northwestern University School of Law, t-jacobi@ law.northwestern.edu. Our thanks to John McGinnis, Nancy Harper, Adrienne Stone, and participants of the University of Melbourne School of Law’s Centre for Comparative Constitutional Studies speaker series. ** J.D., Northwestern University School of Law (2013), [email protected]. -

Congressional Overspeech

ARTICLES CONGRESSIONAL OVERSPEECH Josh Chafetz* Political theater. Spectacle. Circus. Reality show. We are constantly told that, whatever good congressional oversight is, it certainly is not those things. Observers and participants across the ideological and partisan spectrums use those descriptions as pejorative attempts to delegitimize oversight conducted by their political opponents or as cautions to their own allies of what is to be avoided. Real oversight, on this consensus view, is about fact-finding, not about performing for an audience. As a result, when oversight is done right, it is both civil and consensus-building. While plenty of oversight activity does indeed involve bipartisan attempts to collect information and use that information to craft policy, this Article seeks to excavate and theorize a different way of using oversight tools, a way that focuses primarily on their use as a mechanism of public communication. I refer to such uses as congressional overspeech. After briefly describing the authority, tools and methods, and consensus understanding of oversight in Part I, this Article turns to an analysis of overspeech in Part II. The three central features of overspeech are its communicativity, its performativity, and its divisiveness, and each of these is analyzed in some detail. Finally, Part III offers two detailed case studies of overspeech: the Senate Munitions Inquiry of the mid-1930s and the McCarthy and Army-McCarthy Hearings of the early 1950s. These case studies not only demonstrate the dynamics of overspeech in action but also illustrate that overspeech is both continuous across and adaptive to different media environments. Moreover, the case studies illustrate that overspeech can be used in the service of normatively good, normatively bad, and * Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. -

{PDF EPUB} This Town Two Parties and a Funeral Plus Plenty Of

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} This Town Two Parties and a Funeral — plus plenty of valet parking! — in America’s Gilded Capital by This Town: Two Parties and a Funeral--plus plenty of valet parking!--in America's Gilded Capital. Mark Leibovich, chief national correspondent for The New York Times Magazine, previously served for six years as a political correspondent in the Washington bureau of the Times. Earlier he worked for nine years at the Washington Post. Leibovich received a National Magazine Award in 2011. The author selected the title from a list including "Suck-up City:" "You'll Always Have Lunch in This Town Again," and "The Club." After working in Washington, D.C., for 15 years, he learned that This Town imposes on its "actors a reflex toward devious and opportunistic behavior, and a tendency to care about public relations more than any other aspect of their professional lives--and maybe even personal lives." This Town as Washingtonians refer to the place, festers "faux disgust and a wry distance--a verbal tic as a secret handshake." A play on the two-word refrain people in This Town frequently use, "This Town" functions as a cliche of "belonging, knowingness, and self-mocking civic disdain" Then there is "The Club" made up of This Town's city fathers, whose "spinning cabal of people in politics and media can be as potent in D.C. as Congress" The club itself has been known by various names: "Permanent Washington;' "The Political Class," "The Chattering Class," "The Usual Suspects," "The Beltway Establishment," "The Chamber," "The Echo-System:' "The Gang of 500," "The Movable Mass,' and others. -

Mark Leibovich Chief National Correspondent New York Times

Inspicio journalism Introduction to Mark Leibovich. 1:14 min. Interview: Raymond Elman. Camera: Lee Skye. Video Editing: Wesley Verdier. Production: Zaida Duvers. Recorded: 11/17/2018, Miami Book Fair. Mark Leibovich Chief National Correspondent for the New York Times Magazine, Author By Elman + Skye + Verdier + Duvers ARK LEIBOVICH (b.1965) is the chief national correspondent for the New York Times Magazine, Mbased in Washington, D.C. He is known for his profiles of political and media figures. He also writes the Times magazine’s “Your Fellow Americans” column about politics, media, and public life. He came to the Times in 2006 after 10 years at the Washington Post and three at the San Jose Mercury News. Leibovich got his start as a journalist writing for Boston’s alternative weekly, The Phoenix, where he worked for four years. In addition to his political writing, Leibovich has also written: The New Imperialists, a collection of profiles of technology pioneers; Citizens of the Green Room, an anthology of Leibovich’s profiles in the New York Times and Washington Post; and Big Game: The NFL in Dangerous Times, a behind- the-scenes look at the owners, and commissioner, of the National Football League. Leibovich also appears frequently as a guest on MSNBC’s Morning Joe, and Deadline: White House, NPR’s On the Media, and other public affairs programs. Mr. Leibovich grew up in the Boston area, and attended the University of Michigan. He lives in Washington, D.C., with his wife and three daughters. We divided our video interview with Mr. Leibovich into two sections: Life & Career NFL Football For the football discussion, we included Stephanie Anderson, who is the partner of a former NFL player suffering from CTE, the concussion-induced brain disease that has afflicted many NFL players. -

How People Make Sense of Trump and Why It Matters for Racial Justice

Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, Vol. 8, No.1/2, 2018, pp. 107-136. How People Make Sense of Trump and Why It Matters for Racial Justice Will Penman Doug Cloud+ Scholars, journalists, pundits and others have criticized the racist, anti-queer, anti-Semitic, Islamophobic, and xeno- phobic rhetoric that pervades the Trump campaign and presidency. At the same time, commentators have expended a vast number of words analyzing Trump’s character: why does he do the things he does? We ask, how do the latter (analyses of Trump’s character) help explain the former (Trump’s racist statements)? Through a close rhetorical analysis of 50 diverse examples of Trump criticism, we reveal four prevailing characterizations or “archetypes” of Trump: Trump the Acclaim-Seeker, Trump the Sick Man, Trump the Authoritarian, and Trump the Idiot. Each arche- type explains Trump’s racism in a different way, with significant consequences for social critique. For example, the Trump the Idiot archetype dismisses his racist statements as a series of terrible gaffes, whereas Trump the Authori- tarian explains them as an actualization of white supremacy. We trace the benefits and tradeoffs of each archetype for resisting white supremacy. Keywords: Donald Trump, white supremacy, identity, rhetoric, archetypes Read enough critiques of Donald Trump—the president and the candidate—and you’re likely to be struck by three things: 1) there are a great many of them, 2) they expend significant effort analyzing Trump’s character as a way of explaining why he does what he does, and 3) they are repetitive—certain characterizations surface over and over and become familiar as explanations (e.g., the idea that Trump does what he does because he is an incompetent idiot). -

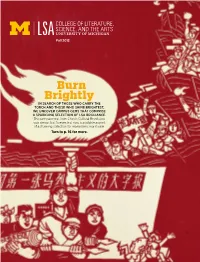

Burn Brightly in Search of Those Who Carry the Torch and Those Who Shine Brightest, We Uncover Campus Gems That Comprise a Sparkling Selection of LSA Brilliance

Fall 2013 Burn Brightly IN SEARCH OF THOSE WHO CARRY THE TORCH AND THOSE WHO SHINE BRIGHTEST, WE UNCOVER CAMPUS GEMS THAT COMPRISE A SPARKLING SELECTION OF LSA BRILLIANCE. This rare papercut from China’s Cultural Revolution was almost lost forever, but now is available as part of a stunning collection for researchers worldwide. Turn to p. 16 for more. UPDATE Lighting the Way IT TAKES A LOT OF ENERGY to make something burn brightly. The same is true of an idea or a person. It’s easier to go along as one of crowd. The status quo is comfortable. It takes curiosity, stamina, and that all-important spark to kindle greatness, and it takes a Michigan Victor to keep the spark burning as a flame. Leaders and Vic- tors shine brighter than their counterparts because they have figured out how to burn — even amid shadows. But how do they ignite and feed their individual sparks? The Victors in this issue all exemplify one consistent theme: Their brilliance defies logical, run-of-the-mill thinking. Just as the massive secrets of the universe can be un- locked by the tiniest particles, Victors are brave enough to embrace the contradictory. Victors who help others get ahead. Those who serve others become leaders. Victors who give get the most back. Those who strive for deeper understanding throw out much of what they think they know. Leaders who have found a way to unleash their light didn’t just pull it out from under the bushel. They used the bushel itself to light a thousand other fires. -

The Academy of Political Science 475 Riverside Drive · Suite 1274 · New York, New York 10115-1274

The Academy of Political Science 475 Riverside Drive · Suite 1274 · New York, New York 10115-1274 (212) 870-2500 · FAX: (212) 870-2202 · [email protected] · http://www.psqonline.org POLITICAL SCIENCE QUARTERLY Volume 123 · Number 3 · Fall 2008 No part of this article may be copied, downloaded, stored, further transmitted, transferred, distributed, altered, or otherwise used, in any form or by any means, except: one stored electronic and one paper copy of any article solely for your personal, non- commercial use, or with prior written permission of The Academy of Political Science. Political Science Quarterly is published by The Academy of Political Science. Contact the Academy for further permission regarding the use of this work. Political Science Quarterly Copyright © 2008 by The Academy of Political Science. All rights reserved. Psychological Reflections on Barack Obama and John McCain: Assessing the Contours of a New Presidential Administration STANLEY A. RENSHON On 20 January 2009, either Barack Obama or John McCain will place his hand on a bible, swear to uphold and defend the Constitution, and become the forty-fourth president of the United States. The new president will immediately become responsible for the issues on which he campaigned, those that he ignored but for which he will nonetheless be held accountable, and all those unanticipated issues for which he will also be expected to de- vise solutions. Naturally, a new president and administration raise many questions. What will the successful candidate really be like as -

Gedung Putih, Hari Pertama Obama

Untuk Rachel Corrie gadis muda Amerika, aktivis perdamaian yang tubuhnya hancur digilas buldozer Israel Ucapan terimakasih untuk... Suamiku, yang tanpa dukungannya buku ini takkan pernah selesai. Anak-anakku, yang bersabar membiarkanku melewati puluhan hari untuk menulis buku ini. Orangtuaku, teman-temanku, dan semua orang yang mendorongku untuk terus menulis. QR Aliya Publishing, yang telah bersedia menerbitkan buku ini Prolog Obama: Tutankhamon Baru Dunia (?) The United States played a role in the overthrow of a democratically elected Iranian government. (Pidato Obama di Kairo) 4 Juni 2009 Kairo, yang biasanya padat dan bising, pagi itu sangat sepi dan teratur. Ada tamu besar yang akan datang hari itu: Presiden AS ke-44, Barack Husein Obama. Beberapa jalanan utama yang akan dilalui Sang Presiden ditutup untuk umum dan dikawal polisi berseragam putih. Sebagian besar dari 18 juta penduduk kota itu memilih tinggal di rumah daripada berpergian di tengah jalanan yang diblokir di sana-sini. Bahkan terminal bus di dekat Mesjid Sultan dipindahkan supaya tak ada keramaian di mesjid kuno yang akan dikunjungi Obama itu. Tak heran bila Al Dastour, koran independen terbitan Kairo menulis headline, “Hari Ini Obama Datang Ke Mesir Setelah Mengevakuasi Warga Mesir”. Di pasar Khan Al Khalili, Kairo, toko-toko souvenir menjual plakat metal bergambar wajah Pharaoh (Firaun)1 dengan tulisan “Obama, Tutankhamon Baru Dunia”. Tutankhamon adalah Firaun terakhir Dinasti Kedelapanbelas Mesir, hidup pada tahun 1333-1324 sebelum Masehi. Konon dia raja yang berhasil memimpin Mesir melewati masa krisis. Dan agaknya, menurut versi pembuat souvenir itu, Obama adalah Tutankhamon baru yang memimpin dunia yang saat ini sangat dipenuhi oleh krisis, konflik, dan pertumpahan darah. -

Fall 2015/Winter 2016 Highlights

Highlights Fall 2015—Winter 2016 The 10th Anniversary Celebration In Washington, DC Here is a recipe for an off-campus program. Combine a full load of academic courses with a minimum of four days a week at work in an office in the nation’s capital. Secure the support of the provost, deans, department chairs, faculty and staff on campus and Michigan alumni in Washington, DC. Recruit undergraduate students from all majors. Provide financial aid. Find faculty, staff and graduate student assistants to teach a required research seminar and electives, prepare the students for their time away from campus, and process the paperwork. Find a place for the students to live in Washington. Match students with local alumni mentors. Invite guest speakers. Go on field trips. Throw dinner parties. Rejoice with the students when they are happy, and encourage them when they are stressed out. Send them back to Ann Arbor after 100 days. Debrief them. Put a red, white and blue cord over their black gowns when they graduate. Keep in touch with them forever. Repeat. More precisely, repeat 20 times. That is what the Michigan in Washington Program is celebrating in its 10th Anniversary year. 10th Anniversary, The First Day: Dinner for 150 at the National Press Club, Washington, DC Program Founder and Director Edie Goldenberg presided over a three-course dinner for 150 current students, former students, Washington-area alumni supporters, faculty, staff, current and former graduate student assistants, and well-wishers Friday evening, October 23, 2015 at the National Press Club, one of the largest venues in town. -

LEAH WRIGHT RIGUEUR: So Thank You All for Joining Us Here Tonight, and Thank You, Mark, So Much for Braving the Polar Vortex to Come out to Cambridge Tonight

LEAH WRIGHT RIGUEUR: So thank you all for joining us here tonight, and thank you, Mark, so much for braving the polar vortex to come out to Cambridge tonight. So I think it will be a really interesting and, hopefully, provocative conversation. But I thought we'd start off just a little bit by talking about your book. And I'm really interested in where this book comes from, why did you write it, and why this shift away from electoral politics into sports politics, of all things? MARK LEIBOVICH: Well, that wasn't the intent. The intent wasn't the sports politics part. I mean, essentially, I've been covering national politics for about 20 years, and after the last campaign, I needed a break from politics. So what better place to take a break from politics than into the NFL during the Trump years, right? So that didn't work out terribly well. I mean, this was-- look, football has been a great passion of mine for a long time. I'd written a magazine story on Tom Brady in 2015 and then the NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell in 2016. So I sort of had an annual side project of just one big magazine story a year on NFL figures, and that indicated to me that there was a lot more to that world that I wanted to get to know. And also, just there was not a great sort of body of literature of honest writing about the NFL. There's a lot of glorification, a lot of insider accounts, but this was more of an outsider account that frankly gave away some secret handshakes and caused some discomfort within the league, which I was happy to do. -

Donald Trump, Clean Government Reformer?

Donald Trump, Clean Government Reformer? Candidate Trump Used Campaign Rhetoric Promising to “Drain the Swamp” of Special Interest Influence. Will President Trump Keep His Good Government Campaign Promises? By Rick Claypool, research director for Public Citizen president’s office Nov. 15, 2016 – During President-Elect Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign, the media personality-turned-politician called out opponents real and perceived as “dishonest and corrupt,”1 “hypocrites”2 and “liars.”3 Because Trump campaigned on contrasting his supposed trustworthiness with political opponents Republican and Democrat alike,4 the consistency between the politician’s words and deeds bear special scrutiny, in particular with regards to campaign promises about ethics reforms and anticorruption policies. This report documents statements made by the president-elect during campaign speeches, in the primary and presidential debates, on Twitter and elsewhere that political observers should bear in mind when weighing whether President Trump is meeting the expectations that candidate Trump raised during the campaign to persuade voters his administration would reduce special interest influence. 1 Kenneth T. Walsh, “Trump: Media Is 'Dishonest and Corrupt',” U.S. News & World Report (Aug. 15, 2016), http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-08-15/trump-media-is-dishonest-and-corrupt 2 “So many self-righteous hypocrites. Watch their poll numbers - and elections - go down!” Tweet via @realDonald Trump (10:12 AM - 9 Oct 2016) https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/785120729364922369 3 “The reason lyin' Ted Cruz has lost so much of the evangelical vote is that they are very smart and just don't tolerate liars-a big problem!” Tweet via @realDonald Trump (8:28 AM - 17 Mar 2016), https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/710442630207901696 4 Mostly notably “Lyin’ Ted” Cruz and “Crooked Hillary” Clinton. -

MR. PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE: WHOM WOULD YOU NOMINATE?” Stuart Minor Benjamin & Mitu Gulati*

“MR. PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE: WHOM WOULD YOU NOMINATE?” Stuart Minor Benjamin & Mitu Gulati* Presidential candidates compete on multiple fronts for votes. Who is more likeable? Who will negotiate more effectively with allies and adversaries? Who has the better vice-presidential running mate? Who will make better appointments to the Supreme Court and the cabinet? This last question is often discussed long before the inauguration, for the impact of a secretary of state or a Supreme Court justice can be tremendous. Despite the importance of such appointments, we do not expect candidates to compete on naming the better slates of nominees. For the candidates themselves, avoiding competition over nominees in the pre-election context has personal benefits—in particular, enabling them to keep a variety of supporters working hard on the campaign in the hope of being chosen as nominees. But from a social perspective, this norm has costs. This Article proposes that candidates be induced out of the status quo. In the current era of candidates responding to internet queries and members of the public asking questions via YouTube, it is plausible that the question—“Whom would you nominate (as secretary of state or for the Supreme Court)?”—might be asked in a public setting. If one candidate is behind in the race, he can be pushed to answer the question—and perhaps increase his chances of winning the election. * Professors of Law, Duke Law School. Thanks to Scott Baker, Steve Choi, Michael Gerhardt, Jay Hamilton, Christine Hurt, Kimberly Krawiec, David Levi, Joan Magat, Mike Munger, Eric Posner, Richard Posner, Arti Rai, Larry Ribstein, David Rohde, Larry Solum, Sharon Spray, Eugene Volokh, and Ernest Young for comments.