MR. PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE: WHOM WOULD YOU NOMINATE?” Stuart Minor Benjamin & Mitu Gulati*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Misrepresented Road to Madame President: Media Coverage of Female Candidates for National Office

THE MISREPRESENTED ROAD TO MADAME PRESIDENT: MEDIA COVERAGE OF FEMALE CANDIDATES FOR NATIONAL OFFICE by Jessica Pinckney A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Government Baltimore, Maryland May, 2015 © 2015 Jessica Pinckney All Rights Reserved Abstract While women represent over fifty percent of the U.S. population, it is blatantly clear that they are not as equally represented in leadership positions in the government and in private institutions. Despite their representation throughout the nation, women only make up twenty percent of the House and Senate. That is far from a representative number and something that really hurts our society as a whole. While these inequalities exist, they are perpetuated by the world in which we live, where the media plays a heavy role in molding peoples’ opinions, both consciously and subconsciously. The way in which the media presents news about women is not always representative of the women themselves and influences public opinion a great deal, which can also affect women’s ability to rise to the top, thereby breaking the ultimate glass ceilings. This research looks at a number of cases in which female politicians ran for and/or were elected to political positions at the national level (President, Vice President, and Congress) and seeks to look at the progress, or lack thereof, in media’s portrayal of female candidates running for office. The overarching goal of the research is to simply show examples of biased and unbiased coverage and address the negative or positive ways in which that coverage influences the candidate. -

The Warren Court and the Pursuit of Justice, 50 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 50 | Issue 1 Article 4 Winter 1-1-1993 The aW rren Court And The Pursuit Of Justice Morton J. Horwitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Morton J. Horwitz, The Warren Court And The Pursuit Of Justice, 50 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 5 (1993), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol50/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE WARREN COURT AND THE PURSUIT OF JUSTICE MORTON J. HoRwiTz* From 1953, when Earl Warren became Chief Justice, to 1969, when Earl Warren stepped down as Chief Justice, a constitutional revolution occurred. Constitutional revolutions are rare in American history. Indeed, the only constitutional revolution prior to the Warren Court was the New Deal Revolution of 1937, which fundamentally altered the relationship between the federal government and the states and between the government and the economy. Prior to 1937, there had been great continuity in American constitutional history. The first sharp break occurred in 1937 with the New Deal Court. The second sharp break took place between 1953 and 1969 with the Warren Court. Whether we will experience a comparable turn after 1969 remains to be seen. -

Student's Name

California State & Local Government In Crisis, 6th ed., by Walt Huber CHAPTER 6 QUIZ - © January 2006, Educational Textbook Company 1. Which of the following is NOT an official of California's plural executive? (p. 78) a. Attorney General b. Speaker of the Assembly c. Superintendent of Public Instruction d. Governor 2. Which of the following are requirements for a person seeking the office of governor? (p. 78) a. Qualified to vote b. California resident for 5 years c. Citizen of the United States d. All of the above 3. Which of the following is NOT a gubernatorial power? (p. 79) a. Real estate commissioner b. Legislative leader c. Commander-in-chief of state militia d. Cerimonial and political leader 4. What is the most important legislative weapon the governor has? (p. 81) a. Line item veto b. Full veto c. Pocket veto d. Final veto 5. What is required to override a governor's veto? (p. 81) a. Simple majority (51%). b. Simple majority in house, two-thirds vote in senate. c. Two-thirds vote in both houses. d. None of the above. 6. Who is considered the most important executive officer in California after the governor? (p. 83) a. Lieutenant Governor b. Attorney General c. Secretary of State d. State Controller 1 7. Who determines the policies of the Department of Education? (p. 84) a. Governor b. Superintendent of Public Instruction c. State Board of Education d. State Legislature 8. What is the five-member body that is responsible for the equal assessment of all property in California? (p. -

Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin As V.P. Pick

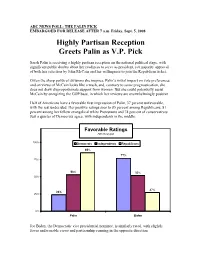

ABC NEWS POLL: THE PALIN PICK EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 7 a.m. Friday, Sept. 5, 2008 Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin as V.P. Pick Sarah Palin is receiving a highly partisan reception on the national political stage, with significant public doubts about her readiness to serve as president, yet majority approval of both her selection by John McCain and her willingness to join the Republican ticket. Given the sharp political divisions she inspires, Palin’s initial impact on vote preferences and on views of McCain looks like a wash, and, contrary to some prognostication, she does not draw disproportionate support from women. But she could potentially assist McCain by energizing the GOP base, in which her reviews are overwhelmingly positive. Half of Americans have a favorable first impression of Palin, 37 percent unfavorable, with the rest undecided. Her positive ratings soar to 85 percent among Republicans, 81 percent among her fellow evangelical white Protestants and 74 percent of conservatives. Just a quarter of Democrats agree, with independents in the middle. Favorable Ratings ABC News poll 100% Democrats Independents Republicans 85% 77% 75% 53% 52% 50% 27% 24% 25% 0% Palin Biden Joe Biden, the Democratic vice presidential nominee, is similarly rated, with slightly fewer unfavorable views and partisanship running in the opposite direction. Palin: Biden: Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable All 50% 37 54% 30 Democrats 24 63 77 9 Independents 53 34 52 31 Republicans 85 7 27 60 Men 54 37 55 35 Women 47 36 54 27 IMPACT – The public by a narrow 6-point margin, 25 percent to 19 percent, says Palin’s selection makes them more likely to support McCain, less than the 12-point positive impact of Biden on the Democratic ticket (22 percent more likely to support Barack Obama, 10 percent less so). -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

Suffolk University Virginia General Election Voters SUPRC Field

Suffolk University Virginia General Election Voters AREA N= 600 100% DC Area ........................................ 1 ( 1/ 98) 164 27% West ........................................... 2 51 9% Piedmont Valley ................................ 3 134 22% Richmond South ................................. 4 104 17% East ........................................... 5 147 25% START Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for Suffolk University and I would like to get your opinions on some political questions. We are calling Virginia households statewide. Would you be willing to spend three minutes answering some brief questions? <ROTATE> or someone in that household). N= 600 100% Continue ....................................... 1 ( 1/105) 600 100% GEND RECORD GENDER N= 600 100% Male ........................................... 1 ( 1/106) 275 46% Female ......................................... 2 325 54% S2 S2. Thank You. How likely are you to vote in the Presidential Election on November 4th? N= 600 100% Very likely .................................... 1 ( 1/107) 583 97% Somewhat likely ................................ 2 17 3% Not very/Not at all likely ..................... 3 0 0% Other/Undecided/Refused ........................ 4 0 0% Q1 Q1. Which political party do you feel closest to - Democrat, Republican, or Independent? N= 600 100% Democrat ....................................... 1 ( 1/110) 269 45% Republican ..................................... 2 188 31% Independent/Unaffiliated/Other ................. 3 141 24% Not registered -

Earl Warren: a Political Biography, by Leo Katcher; Warren: the Man, the Court, the Era, by John Weaver

Indiana Law Journal Volume 43 Issue 3 Article 14 Spring 1968 Earl Warren: A Political Biography, by Leo Katcher; Warren: The Man, The Court, The Era, by John Weaver William F. Swindler College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Judges Commons, and the Legal Biography Commons Recommended Citation Swindler, William F. (1968) "Earl Warren: A Political Biography, by Leo Katcher; Warren: The Man, The Court, The Era, by John Weaver," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 43 : Iss. 3 , Article 14. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol43/iss3/14 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS EARL WARREN: A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY. By Leo Katcher. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967. Pp. i, 502. $8.50. WARREN: THEi MAN, THE COURT, THE ERA. By John D. Weaver. Boston: Little. Brown & Co., 1967. Pp. 406. $7.95. Anyone interested in collecting a bookshelf of serious reading on the various Chief Justices of the United States is struck at the outset by the relative paucity of materials available. Among the studies of the Chief Justices of the twentieth century there is King's Melville Weston, Fuller,' which, while not definitive, is reliable and adequate enough to have merited reprinting in the excellent paperback series being edited by Professor Philip Kurland of the University of Chicago. -

Historical Log of Judicial Appointments 1959-Present Candidates Nominated Appointed 1959 - Supreme Court - 3 New Positions William V

Historical Log of Judicial Appointments 1959-Present Candidates Nominated Appointed 1959 - Supreme Court - 3 new positions William V. Boggess William V. Boggess John H. Dimond Robert Boochever Robert Boochever Walter Hodge J. Earl Cooper John H. Dimond Buell A. Nesbett** Edward V. Davis Walter Hodge* 1959 by Governor William Egan John H. Dimond M.E. Monagle John S. Hellenthal Buell A. Nesbett* Walter Hodge * nominated for Chief Justice Verne O. Martin M.E. Monagle Buell A. Nesbett Walter Sczudlo Thomas B. Stewart Meeting Date 7/16-17/1959 **appointed Chief Justice 1959 - Ketchikan/Juneau Superior - 2 new positions Floyd O. Davidson E.P. McCarron James von der Heydt Juneau James M. Fitzgerald Thomas B. Stewart Walter E. Walsh Ketchikan Verne O. Martin James von der Heydt 1959 by Governor William Egan E.P. McCarron Walter E. Walsh Thomas B. Stewart James von der Heydt Walter E. Walsh Meeting Date 10/12-13/1959 1959 - Nome Superior - new position James M. Fitzgerald Hubert A. Gilbert Hubert A. Gilbert Hubert A. Gilbert Verne O. Martin 1959 by Governor William Egan Verne O. Martin James von der Heydt Meeting Date 10/12-13/1959 1959 - Anchorage Superior - 3 new positions Harold J. Butcher Harold J. Butcher J. Earl Cooper Henry Camarot J. Earl Cooper Edward V. Davis J. Earl Cooper Ralph Ralph H. Cottis James M. Fitzgerald H. Cottis Roger Edward V. Davis 1959 by Governor William Egan Cremo Edward James M. Fitzgerald V. Davis James Stanley McCutcheon M. Fitzgerald Everett Ralph E. Moody W. Hepp Peter J. Kalamarides Verne O. Martin Stanley McCutcheon Ralph E. -

The Filibuster and Reconciliation: the Future of Majoritarian Lawmaking in the U.S

The Filibuster and Reconciliation: The Future of Majoritarian Lawmaking in the U.S. Senate Tonja Jacobi†* & Jeff VanDam** “If this precedent is pushed to its logical conclusion, I suspect there will come a day when all legislation will be done through reconciliation.” — Senator Tom Daschle, on the prospect of using budget reconciliation procedures to pass tax cuts in 19961 Passing legislation in the United States Senate has become a de facto super-majoritarian undertaking, due to the gradual institutionalization of the filibuster — the practice of unending debate in the Senate. The filibuster is responsible for stymieing many legislative policies, and was the cause of decades of delay in the development of civil rights protection. Attempts at reforming the filibuster have only exacerbated the problem. However, reconciliation, a once obscure budgetary procedure, has created a mechanism of avoiding filibusters. Consequently, reconciliation is one of the primary means by which significant controversial legislation has been passed in recent years — including the Bush tax cuts and much of Obamacare. This has led to minoritarian attempts to reform reconciliation, particularly through the Byrd Rule, as well as constitutional challenges to proposed filibuster reforms. We argue that the success of the various mechanisms of constraining either the filibuster or reconciliation will rest not with interpretation by † Copyright © 2013 Tonja Jacobi and Jeff VanDam. * Professor of Law, Northwestern University School of Law, t-jacobi@ law.northwestern.edu. Our thanks to John McGinnis, Nancy Harper, Adrienne Stone, and participants of the University of Melbourne School of Law’s Centre for Comparative Constitutional Studies speaker series. ** J.D., Northwestern University School of Law (2013), [email protected]. -

CHIEF JUSTICE WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT EARL WARREN-T

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 67 JANUARY, 1958 NUMBER 3 CHIEF JUSTICE WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT EARL WARREN-t Delivered at the Yale University ceremonies commemorating the centennial of the birth of William Howard Taft. WE commemorate a centennial. In an arbitrary sense, the passage of a hundred years, like any other unit of measure, is in itself neither important nor unimportant; its only significance derives from the transactions and changes to which it is applied. But, from the standpoint of perspective and, more especi- ally, as a review of the course of a dynamic country which, by history's reckon- ing, still is young, but which within ten decades has attained the position of foremost influence in the free world, it is a long period ponderous with impli- cation. The population has grown from less than 32,000,000 to more than 165,000,000; it has been a time of extraordinary mechanical and scientific progress; abroad, old civilizations have fallen and new societies take their place; ancient values have been tested and some have been dismissed and some revised; the world has grown smaller in every way. Considered in these terms the century, and the seventy-two years which William Howard Taft spent in it, assume stature, dimension and character. Apart from the pervasive personality, the Taft story is a review of the com- pilations of Martindale, the Ohio Blue Book, and the Official Register of the United States. Actually, it is an odyssey, the narrative of a long journey beset with detours, delays, distraction and a sometimes receding destination. -

Congressional Overspeech

ARTICLES CONGRESSIONAL OVERSPEECH Josh Chafetz* Political theater. Spectacle. Circus. Reality show. We are constantly told that, whatever good congressional oversight is, it certainly is not those things. Observers and participants across the ideological and partisan spectrums use those descriptions as pejorative attempts to delegitimize oversight conducted by their political opponents or as cautions to their own allies of what is to be avoided. Real oversight, on this consensus view, is about fact-finding, not about performing for an audience. As a result, when oversight is done right, it is both civil and consensus-building. While plenty of oversight activity does indeed involve bipartisan attempts to collect information and use that information to craft policy, this Article seeks to excavate and theorize a different way of using oversight tools, a way that focuses primarily on their use as a mechanism of public communication. I refer to such uses as congressional overspeech. After briefly describing the authority, tools and methods, and consensus understanding of oversight in Part I, this Article turns to an analysis of overspeech in Part II. The three central features of overspeech are its communicativity, its performativity, and its divisiveness, and each of these is analyzed in some detail. Finally, Part III offers two detailed case studies of overspeech: the Senate Munitions Inquiry of the mid-1930s and the McCarthy and Army-McCarthy Hearings of the early 1950s. These case studies not only demonstrate the dynamics of overspeech in action but also illustrate that overspeech is both continuous across and adaptive to different media environments. Moreover, the case studies illustrate that overspeech can be used in the service of normatively good, normatively bad, and * Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. -

A New Fourteenth Amendment: the Decline of State Action, Fundamental Rights and Suspect Classifications Under the Burger Court

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 56 Issue 3 Article 6 October 1980 A New Fourteenth Amendment: The Decline of State Action, Fundamental Rights and Suspect Classifications under the Burger Court David F. Schwartz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David F. Schwartz, A New Fourteenth Amendment: The Decline of State Action, Fundamental Rights and Suspect Classifications under the Burger Court, 56 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 865 (1980). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol56/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A "NEW" FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT: THE DECLINE OF STATE ACTION, FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS, AND SUSPECT CLASSIFICATIONS UNDER THE BURGER COURT DAVID F. SCHWARTZ* Headlines and great national debate greeted Warren Court deci- sions in areas such as race relations, legislative apportionment, and the rights of nonracial minorities. However, beneath the spotlight focusing on substantive questions, there existed a more significant procedural orientation toward providing certain interests with extraordinary judi- cial protection from hostile governmental action. In the broad areas of state action, fundamental rights, and suspect classifications, this orien- tation resulted in significant limits on state power. During the 1970's, the Burger Court' demonstrated unmistakable hostility to what had become the traditional legal views in those three areas and thus severely eroded many limitations on state power.