Pipeline Politics in Iran: Power and Property, Dispossession and Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

Novel Hydraulic Structures and Water Management in Iran: a Historical Perspective

Novel hydraulic structures and water management in Iran: A historical perspective Shahram Khora Sanizadeh Department of Water Resources Research, Water Research Institute������, Iran Summary. Iran is located in an arid, semi-arid region. Due to the unfavorable distribution of surface water, to fulfill water demands and fluctuation of yearly seasonal streams, Iranian people have tried to provide a better condition for utilization of water as a vital matter. This paper intends to acquaint the readers with some of the famous Iranian historical water monuments. Keywords. Historic – Water – Monuments – Iran – Qanat – Ab anbar – Dam. Structures hydrauliques et gestion de l’eau en Iran : une perspective historique Résumé. L’Iran est situé dans une région aride, semi-aride. La répartition défavorable des eaux de surface a conduit la population iranienne à créer de meilleures conditions d’utilisation d’une ressource aussi vitale que l’eau pour faire face à la demande et aux fluctuations des débits saisonniers annuels. Ce travail vise à faire connaître certains des monuments hydrauliques historiques parmi les plus fameux de l’Iran. Mots-clés. Historique – Eau – Monuments – Iran – Qanat – Ab anbar – Barrage. I - Introduction Iran is located in an arid, semi-arid region. Due to the unfavorable distribution of surface water, to fulfill water demands and fluctuation of yearly seasonal streams, Iranian people have tried to provide a better condition for utilization of water as a vital matter. Iran is located in the south of Asia between 44º 02´ and 63º 20´ eastern longitude and 25º 03´ to 39º 46´ northern latitude. The country covers an area of about 1.648 million km2. -

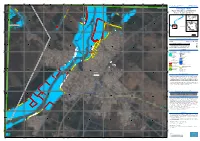

HAMIDIYEH, V1 Hamidiyeh - IRAN 0 0 0 0

254500 255000 255500 256000 256500 257000 257500 258000 48°24'40"E 48°25'0"E 48°25'20"E 48°25'40"E 48°26'0"E 48°26'20"E 48°26'40"E 48°27'0"E GLIDE number: FL-2019-000022-IRN Activation ID: EMSR352 Int. Charter call ID: 601 Product N.: 06HAMIDIYEH, v1 Hamidiyeh - IRAN 0 0 0 0 5 5 Flood - Situation as of 08/04/2019 7 7 8 8 4 4 3 3 Grading - Ready-to-print Map 01 N " 0 h 4 e ' h 9 rk 2 a ° K 1 3 Azerbaijan Turkmenistan Caspian N " 0 Sea 4 ' 9 2 ° 1 Tehran 3 ^ Dasht-e-Azadegan Hamidiyeh (! Khuzestan Iran Iraq RTP01 06 Kuwait Saudi Persian 0 0 Arabia Qatar 0 0 Gulf Gulf of Oman 0 0 7 7 8 8 4 4 3 3 6 km Cartographic Information 1:6000 Full color A1, 200 dpi resolution N " 0 2 ' 0 0,125 0,25 0,5 9 2 ° km 1 3 Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 39N map coordinate system N " 0 2 ' Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system 9 2 ± ° 1 3 Legend 0 0 0 0 5 5 6 6 8 8 Crisis Information Administrative boundaries 4 4 3 3 Flooded Area (08/04/2019 07:38 UTC) Province Flood trace Placenames ! Built Up Grading Placename Destroyed Hydrography Stream Damaged Reservoir Possibly damaged Transportation Grading River Road, Destroyed Stream Road, Damaged Transportation Bridge and elevated highway Road, Possibly damaged N " Primary Road 0 ' General Information 9 2 ° 1 3 Area of Interest Local Road 0 0 0 0 0 0 Cart Track N 6 6 " 8 8 0 ' 4 4 Ahvaz 9 2 3 3 ° 1 3 Map Information Hamidiyeh ! Severe flooding in several provinces of Iran since mid-March, has left 70 people dead. -

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE and HERITAGE Basra Its History, Culture and Heritage

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE CULTURE : ITS HISTORY, BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins Edited by Paul Collins BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins © BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ 2019 ISBN 978-0-903472-36-4 Typeset and printed in the United Kingdom by Henry Ling Limited, at the Dorset Press, Dorchester, DT1 1HD CONTENTS Figures...................................................................................................................................v Contributors ........................................................................................................................vii Introduction ELEANOR ROBSON .......................................................................................................1 The Mesopotamian Marshlands (Al-Ahwār) in the Past and Today FRANCO D’AGOSTINO AND LICIA ROMANO ...................................................................7 From Basra to Cambridge and Back NAWRAST SABAH AND KELCY DAVENPORT ..................................................................13 A Reserve of Freedom: Remarks on the Time Visualisation for the Historical Maps ALEXEI JANKOWSKI ...................................................................................................19 The Pallakottas Canal, the Sealand, and Alexander STEPHANIE -

The Political Economy of the IRGC's Involvement in the Iranian Oil and Gas Industry

The Political Economy of the IRGC’s involvement in the Iranian Oil and Gas Industry: A Critical Analysis MSc Political Science (Political Economy) Thesis Research Project: The Political Economy of Energy University of Amsterdam, Graduate School of Social Sciences 5th June 2020 Author: Hamed Saidi Supervisor: Dr. M. P. (Mehdi) Amineh (1806679) Second reader: Dr. S. (Said) Rezaeiejan [This page is intentionally left blank] 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... 7 Maps ................................................................................................................................................ 8 List of Figures and Tables ................................................................................................................. 10 List of Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 11 I: RESEARCH DESIGN .................................................................................................................................... 13 1.1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

Effect of the Kharkhe Storage Dam on Vulnerability of Downstream Land and the Kharkhe Bondary

American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Environ. Sci., 3 (6): 917-921, 2008 ISSN 1818-6769 © IDOSI Publications, 2008 Effect of the Kharkhe Storage Dam on Vulnerability of Downstream Land and the Kharkhe Bondary 1M. Mohammadpour, 2A. Behnia, 2A. M. Akhoond-Ali and 3A. Telvari 1Department of Hydrology, Shahid Chamran University, Ahvaz, Iran 2Shahid Chamran University, Ahvaz, Iran 3Institude of Watershed Manaagement, Tehran, Iran Abstract: River boundaries, as defined by the state law, comprise the land along and surrounding riverbanks expected to be inundated or flooded during flood events of a 25-year return-period. Construction of large water structures such as dams across rivers may lead to considerable decrease in the flood discharge proportionate to structure size which will in turn result in lower flood probability. Assessment of the vulnerability of river boundary is of great importance due to their rich soil and easy access to irrigation water which makes such riverbank farms economically valuable especially in dry areas. The results of such assessment can be used in land use planning. For the purposes of the present study, a reach of 190 km was selected along the banks of the Karkheh River downstream the Karkheh Storage Dam in southern Iran. Estimations were then made of river flood events prior to constructing the dam with return periods of 2 to 100 years and their corresponding post-construction values for the same periods. Values of flood inundation of the river banks were determined for flood events with different return periods. Using the values thus obtained, the vulnerability curve was plotted for various flood probabilities before and after constructing the dam. -

Analyses of the Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources Components, Drought and Wheat Yield in Semiarid Regions: Karkheh River Basin in Iran

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. (2013) Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/hyp.9747 Analyses of the impact of climate change on water resources components, drought and wheat yield in semiarid regions: Karkheh River Basin in Iran S. Ashraf Vaghefi,1 S. J. Mousavi,1 K. C. Abbaspour,2* R. Srinivasan3 and H. Yang2 1 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Amirkabir University of Technology, Tehran, Iran 2 Eawag, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, PO Box 611, 8600, Dübendorf, Switzerland 3 Texas A&M University, Texas Agricultural Experimental Station, Spatial Science Lab, College Station, TX, 77845, USA Abstract: Water resources availability in the semiarid regions of Iran has experienced severe reduction because of increasing water use and lengthening of dry periods. To better manage this resource, we investigated the impact of climate change on water resources and wheat yield in the Karkheh River Basin (KRB) in the semiarid region of Iran. Future climate scenarios for 2020–2040 were generated from the Canadian Global Coupled Model for scenarios A1B, B1 and A2. We constructed a hydrological model of KRB using the Soil and Water Assessment Tool to project water resources availability. Blue and green water components were modeled with uncertainty ranges for both historic and future data. The Sequential Uncertainty Fitting Version 2 was used with parallel processing option to calibrate the model based on river discharge and wheat yield. Furthermore, a newly developed program called critical continuous day calculator was used to determine the frequency and length of critical periods for precipitation, maximum temperature and soil moisture. -

Water Resources Management in Karkheh Basin-Iran

PROCEEDINGS OF THE 3RD INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ENERGY AND DEVELOPMENT - ENVIRONMENT - BIOMEDICINE Water Resources Management in Karkheh Basin-Iran AMIR HAMZEH HAGHIABI1 , NIKOS E. MASTORAKIS2 1-Department of water engineering Lorestan University Khorramabad, Lorestan Province IRAN [email protected] 2- Technical University of Sofia, BULGARIA– also with the WSEAS Research Department, WSEAS, A.I.Theologou 17-23, Zografou, 15773, Athens, GREECE Abstract: - Karkheh basin is located in the semiarid and arid regions of Western Iran, an area with severe water scarcity. 70% of rainfall is directly evaporated. The potential annual evaporation of the southern and northern regions is 3,600 mm 1,800 mm, respectively. Agriculture plays an important role in the economy of the basin. In the present situation, 3.9 bm3 of water are used for irrigating 378,164 ha of irrigated agriculture (horticulture and field crops), and surface water and groundwater resources provide 63 percent and 37 percent, respectively, of this volume. Of the irrigated area, 76.5% is under cereals (wheat and barely), 23% under pulses, and 0.5% under cultivation of forage, orchards, melons and vegetables, and oil seeds. The area is particularly low in terms of yields, productivity and incomes. Irrigation efficiency in the basin is 28-36 percent and the overall Crop Water Productivity in the basin is about 0.55 kg/m3. In this paper, the specifications of the Karkheh Reservoir Dam & Hydroelectric Power Plant as the biggest dam in history of Iran with total volume of reservoir 7.3 Bm3 and Karkheh irrigation and drainage network project are illustrated. Also the situation of water availability in the basin, surface and groundwater potential and some aspects of water resources management in the basin are considered. -

Khalet Al-Jam‟A. a Bronze and Iron Ages Necropolis Near Bethlehem (Palestine): Results of the 2019 Archaeological Excavations

[Vicino Oriente XXIII (2019), pp. 1-22] KHALET AL-JAM‟A. A BRONZE AND IRON AGES NECROPOLIS NEAR BETHLEHEM (PALESTINE): RESULTS OF THE 2019 ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS Lorenzo Nigro - Daria Montanari - Gaia Cecconi - Sapienza University of Rome Mohammed Ghayyada - Jehad Yasine - Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities - Department of Archaeology and Cultural Heritage In Spring 2019 the Italian-Palestinian joint team of Sapienza University of Rome and the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities of Palestine Dept. of Archaeology and Cultural Heritage resumed rescue excavations at the Necropolis of Khalet al-Jam’a, 2.2 Km south-east from the Church of Nativity in Bethlehem. Works were focused on Tomb A7, identified in 2015, a huge underground burial place, dating back to the Iron IIC (8th-7th century BC), but also including earlier depositions dating from the EB IVB-MB. This suggests that an original EBIV tomb was modified and re-used in the following Middle Bronze and Iron Age. A provisional report of activities and finds is offered below. Keywords: Bethlehem; necropolis; Early Bronze Age IV; Middle Bronze Age; Iron Age II 1. INTRODUCTION In April 2019, the joint team of the Palestinian MOTA-DACH and Sapienza University of Rome1 resumed archaeological activities at the Necropolis of Khalet al-Jam‟a, 2.2 Km south-east from the center of Bethlehem.2 Aim of this season was the excavation of Tomb A7, in the south-western sector of Area A (fig. 1), already recognized and surveyed in 2015, when its entrance was first identified.3 2. TOMB A7 Tomb A7 is quite different from the majority of the tombs in the KJ necropolis. -

Water Crisis in Iran: Codification and Strategies in Urban Water

WATER CRISIS IN IRAN: CODIFICATION AND STRATEGIES IN URBAN WATER Dr H.Motiee*, GH. Manouchehri**, Dr M.R.M. Tabatabai*** * Assistant Professor, Water and Wastewater Eng. Dept., PWIT, P.O.Box 16765-1719, Tehran, Iran.E- mail: [email protected] ** Director of Water and Wastewater Company, Tehran, Iran *** Assistant Professor, Water Eng. Dept., PWIT, P.O.Box 16765-1719, Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT Human civilization has always been in evolution by having direct access to water resources throughout history. Water, with its qualitative and quantitative effects, plays an important role in economic and social develoments. Contrary to other sources, water is not replaceable. By increasing world population and also growth of communities, water and its consumption has become important. This may even become more significant in those countries where the volume of rainfall is limited. Water consumption per capita depends on the culture, kind of activities and climate conditions, which varies in different areas. These differences are such that the variation in water consumption per capita may range between 3.0 to 700 liters per day. Iran is located in southwest Asia with an average annual rainfall of 250 millimeters. It has an arid and semi-arid climate. Water crisis has appeared in Iran as a serious problem. There are mainly two reasons for that: (1) Lack of proper water management and (2) Occurrence of drought. In fact, water crisis can be defined as an unadjustment between water resources and rate of consumption. In this paper attempts have been made to identify factors influencing water crisis in Iran. Solutions are also put forward to control and reduce this for the future. -

Evaluating the Effects of Dam Construction on the Morphological Changes of Downstream Meandering Rivers (Case Study: Karkheh River)

Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research Vol. 7, No. 2, 2017, 1515-1522 1515 Evaluating the Effects of Dam Construction on the Morphological Changes of Downstream Meandering Rivers (Case Study: Karkheh River) Ali Liaghat Arash Adib Hamid Reza Gafouri Civil Engineering Department Civil Engineering Department Civil Engineering Department Engineering Faculty, Shahid Engineering Faculty, Shahid Engineering Faculty, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz Chamran University of Ahvaz Chamran University of Ahvaz Iran Iran Iran Abstract—The establishment of stability in rivers is dependent on the above can be attributed to the produced effect of a variety of factors, and yet the established stability can be morphological changes occurring to the river. The change in interrupted at any moment or time. One factor that can strongly the direction of meanders is one of the most prominent disrupt the stability of rivers is the construction of dams. For this problems regarding the instability of rivers. This change in the study, the identification and evaluation of morphological changes meander direction can seriously threaten the success of projects occurring to the Karkheh River, before and after the that are aimed at controlling floodwater. The threat can be construction of the Karkheh Dam, along with determining the explained by the fact that as meanders change their course and degree of changes to the width and length of the downstream migrate, some installations such as levees and lateral flood- meanders of the river, have been performed with the assistance of controlling installations tend to lose their functionality [1]. In satellite images and by applying the CCHE2D hydrodynamic sections of meanders, there is a high gradient of change in the model. -

Hydraulic Systems As Critical Element in Ecosystem and Structure of Historical City of Shushtar

WALIA journal 31(S3): 229-234, 2015 ISSN 1026-3861 © 2015 WALIA Hydraulic Systems as Critical Element in Ecosystem and Structure of Historical City of Shushtar Sommayeh Shirin Jani 1,* , Sadeq Kahvazi 2, Ahmad Esteghlal 3, Alireza Poursalman 4 1Department of Architecture, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran 2Department of Architecture, Payam Noor University, Tehran, Iran 3Department of Art and Architectural, Yazd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Yazd, Iran 4Department of Art and Architectural, Yazd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Yazd, Iran & PHD student of AGRHEC (American Global Research & Higher Education complex Subdivision: American Higher education University(AWHU) Abstract: Shushtar hydraulic systems which includes over thirteen dams, bridges, mills and waterfalls is considered as one of the great Persian architecture works which has been registered as Iran's 10th cultural heritage site on the United Nations' list in 2009, and now, it is indeed recognized as the heritage of the whole world. This collection, from the beginning of the formation in the 9th century BC, had a significant influence on urban ecology, urban spatial structure and the promotion of residents living besides supplying drinking water and agriculture in the region. It should be noted that the huge collection is the concrete realization of environmental technology, as one of the basic conditions for sustainable development in the urban structure. In this paper, after reviewing the effects of these structures on Shushtar ecosystems, their role in