Robert Burns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

The Silver Tassie

The Silver Tassie MY BONIE MARY An old Jacobite ballad rewritten by the Bard. A silver tassie is a silver goblet and the Ferry which is mentioned in the poem is Queensferry, now the site of the two bridges which span the Forth, a short distance from Edinburgh. Go fetch to me a pint 0' wine, And fill it in a silver tassie; That I may drink before I go, A service to my bonie lassie: The boat rocks at the Pier 0' Leith, Fu' loud the wind blaws frae the Ferry, The ship rides by the Berwick-Law, And I maun leave my bonie Mary. maun = must The trumpets sound, the banners fly The glittering spears are ranked ready, The shouts 0' war are heard afar, The battle closes deep and bloody. It's not the roar 0' sea or shore, Wad mak me longer wish to tarry; Nor shouts 0' war that's heard afar- It's leaving thee, my bonie Mary! Afion Water This is a particularly lovely piece which is always a great favourite when sung at any Bums gathering. It refers to the River Afion, a small river, whose beauty obviously greatly enchanted the Bard. Flow gently, sweet Afcon, among thy green braes! braes = banks Flow gently, I'll sing thee a song in thy praise! My Mary's asleep by thy murmuring stream - Flow gently, sweet Afton, disturb not her dream! Thou stock-dove whose echo resounds thro' the glen, stuck dm =a wood pipn Ye wild whistling blackbirds in yon thorny den, yon = yonder Thou green-crested lapwing, thy screaming forbear, I charge you, disturb not my slumbering Fair! How lofey, sweet Afion, thy neighbouring hills, Far markd with the courses of clear, winding -

An Afternoon at the Proms 24 March 2018

AN AFTERNOON AT THE PROMS 24 MARCH 2018 CONCERT PROGRAM MELBOURNE SIR ANDREW DAVIS TASMIN SYMPHONY LITTLE ORCHESTRA Courtesy B Ealovega Established in 1906, the Chief Conductor of the Tasmin Little has performed Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Melbourne Symphony Melbourne Symphony in prestigious venues Sir Andrew Davis conductor Orchestra (MSO) is an Orchestra, Sir Andrew such as Carnegie Hall, the arts leader and Australia’s Davis is also Music Director Concertgebouw, Barbican Tasmin Little violin longest-running professional and Principal Conductor of Centre and Suntory Hall. orchestra. Chief Conductor the Lyric Opera of Chicago. Her career encompasses Sir Andrew Davis has been He is Conductor Laureate performances, masterclasses, Elgar In London Town at the helm of MSO since of both the BBC Symphony workshops and community 2013. Engaging more than Orchestra and the Toronto outreach work. Vaughan Williams The Lark Ascending 3 million people each year, Symphony, where he has Already this year she has the MSO reaches a variety also been named interim Vaughan Williams English Folksong Suite appeared as soloist and of audiences through live Artistic Director until 2020. in recital around the UK. performances, recordings, Britten Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra In a career spanning more Recordings include Elgar’s TV and radio broadcasts than 40 years he has Violin Concerto with Sir Wood Fantasia on British Sea Songs and live streaming. conducted virtually all the Andrew Davis and the Royal Elgar Pomp and Circumstance March No.1 Sir Andrew Davis gave his world’s major orchestras National Scottish Orchestra inaugural concerts as the and opera companies, and (Critic’s Choice Award in MSO’s Chief Conductor in at the major festivals. -

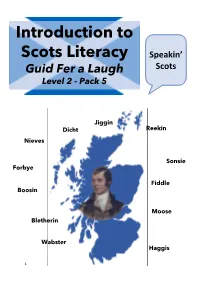

Introduction to Scots Literacy

Introduction to Scots Literacy Speakin’ Scots Guid Fer a Laugh Level 2 - Pack 5 Jiggin Dicht Reekin Nieves Sonsie Forbye Fiddle Boosin Moose Bletherin Wabster Haggis 1 Introduction to Guid Fer A Laugh We are part of the City of Edinburgh Council, South West Adult Learning team and usually deliver ‘Guid Fer a Laugh’ sessions for community groups in South West Edinburgh. Unfortunately, we are unable to meet groups due to Covid-19. Good news though, we have adapted some of the material and we hope you will join in at home. Development of Packs We plan to develop packs from beginner level 1 to 5. Participants will gradually increase in confidence and by level 5, should be able to: read, recognise, understand and write in Scots. Distribution During Covid-19 During Covid-19 restrictions we are emailing packs to community forums, organisations, groups and individuals. Using the packs The packs can be done in pairs, small groups or individually. They are being used by: families, carers, support workers and individuals. The activities are suitable for all adults but particularly those who do not have access to computer and internet. Adapting Packs The packs can be adapted to suit participants needs. For example, the Pilmeny Development Project used The Scot Literacy Pack as part of a St Andrews Day Activity Pack which was posted out to 65 local older people. In the pack they included the Scot Literacy Pack 1 and 2, crosswords, short bread and a blue pen. Please see photo. 2 The Aims of the Session – Whit’s it a’aboot? • it’s about learning Scots language and auld words • takes a look at Scots comedy, songs, poetry and writing • hae a guid laugh at ourselves and others Feedback fae folk This is pack number five and we move on a little to Level 2. -

RBWF Burns Chronicle Index

A Directory To the Articles and Features Published in “The Burns Chronicle” 1892 – 2005 Compiled by Bill Dawson A “Merry Dint” Publication 2006 The Burns Chronicle commenced publication in 1892 to fulfill the ambitions of the recently formed Burns Federation for a vehicle for “narrating the Burnsiana events of the year” and to carry important articles on Burns Clubs and the developing Federation, along with contributions from “Burnessian scholars of prominence and recognized ability.” The lasting value of the research featured in the annual publication indicated the need for an index to these, indeed the 1908 edition carried the first listings, and in 1921, Mr. Albert Douglas of Washington, USA, produced an index to volumes 1 to 30 in “the hope that it will be found useful as a key to the treasures of the Chronicle” In 1935 the Federation produced an index to 1892 – 1925 [First Series: 34 Volumes] followed by one for the Second Series 1926 – 1945. I understand that from time to time the continuation of this index has been attempted but nothing has yet made it to general publication. I have long been an avid Chronicle collector, completing my first full set many years ago and using these volumes as my first resort when researching any specific topic or interest in Burns or Burnsiana. I used the early indexes and often felt the need for a continuation of these, or indeed for a complete index in a single volume, thereby starting my labour. I developed this idea into a guide categorized by topic to aid research into particular fields. -

How Robert Burns Captured America James M

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 30 | Issue 1 Article 25 1998 How Robert Burns Captured America James M. Montgomery Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Montgomery, James M. (1998) "How Robert Burns Captured America," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 30: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol30/iss1/25 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James M. Montgomery How Robert Burns Captured America Before America discovered Robert Bums, Robert Bums had discovered America. This self-described ploughman poet knew well the surge of freedom which dominated much of Europe and North America in the waning days of the eight eenth century. Bums understood the spirit and the politics of the fledgling United States. He studied the battles of both ideas and infantry. Check your knowledge of American history against Bums's. These few lines from his "Ballad on the American War" trace the Revolution from the Boston Tea Party, through the Colonists' invasion of Canada, the siege of Boston, the stalemated occupation of Philadelphia and New York, the battle of Saratoga, the southern campaign and Clinton's failure to support Cornwallis at Yorktown. Guilford, as in Guilford Court House, was the family name of Prime Minister Lord North. When Guilford good our Pilot stood, An' did our hellim thraw, man, Ae night, at tea, began a plea, Within America, man: Then up they gat to the maskin-pat, And in the sea did jaw, man; An' did nae less, in full Congress, Than quite refuse our law, man. -

Comprehension – Robert Burns – Y5m/Y6d – Brainbox Remembering Burns Robert Burns May Be Gone, but He Will Never Be Forgotten

Robert Burns Who is He? Robert Burns is one of Scotland’s most famous poets and song writers. He is widely regarded as the National Poet of Scotland. He was born in Ayrshire on the 25th January, 1759. Burns was from a large family; he had six other brothers and sisters. He was also known as Rabbie Burns or the Ploughman Poet. Childhood Burns was the son of a tenant farmer. As a child, Burns had to work incredibly long hours on the farm to help out. This meant that he didn’t spend much time at school. Even though his family were poor, his father made sure that Burns had a good education. As a young man, Burns enjoyed reading poetry and listening to music. He also enjoyed listening to his mother sing old Scottish songs to him. He soon discovered that he had a talent for writing and wrote his first song, Handsome Nell, at the age of fifteen. Handsome Nell was a love song, inspired by a farm servant named Nellie Kilpatrick. Becoming Famous In 1786, he planned to emigrate to Jamaica. His plans were changed when a collection of his songs and poems were published. The first edition of his poetry was known as the Kilmarnock edition. They were a huge hit and sold out within a month. Burns suddenly became very popular and famous. That same year, Burns moved to Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland. He was made very welcome by the wealthy and powerful people who lived there. He enjoyed going to parties and living the life of a celebrity. -

"Auld Lang Syne" G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Selected Essays on Robert Burns by G. Ross Roy Robert Burns Collections 3-1-2018 "Auld Lang Syne" G. Ross Roy University of South Carolina - Columbia Publication Info 2018, pages 77-83. (c) G. Ross Roy, 1984; Estate of G. Ross Roy; and Studies in Scottish Literature, 2019. First published as introduction to Auld Lang Syne, by Robert Burns, Scottish Poetry Reprints, 5 (Greenock: Black Pennell, 1984). This Chapter is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Essays on Robert Burns by G. Ross Roy by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “AULD LANG SYNE” (1984) A good case can be made that “Auld Lang Syne” is the best known “English” song in the world, & perhaps the best known in any language if we except national anthems. The song is certainly known throughout the English-speaking world, including countries which were formerly part of the British Empire. It is also known in most European countries, including Russia, as well as in China and Japan. Before and during the lifetime of Robert Burns the traditional Scottish song of parting was “Gude Night and Joy be wi’ You a’,” and there is evidence that despite “Auld Lang Syne” Burns continued to think of the older song as such. He wrote to James Johnson, for whom he was writing and collecting Scottish songs to be published in The Scots Musical Museum (6 vols. Edinburgh, 1787-1803) about “Gude Night” in 1795, “let this be your last song of all the Collection,” and this more than six years after he had written “Auld Lang Syne.” When Johnson published Burns’s song it enjoyed no special place in the Museum, but he followed the poet’s counsel with respect to “Gude Night,” placing it at the end of the sixth volume. -

Robert Burns and a Red Red Rose Xiaozhen Liu North China Electric Power University (Baoding), Hebei 071000, China

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 311 1st International Symposium on Education, Culture and Social Sciences (ECSS 2019) Robert Burns and A Red Red Rose Xiaozhen Liu North China Electric Power University (Baoding), Hebei 071000, China. [email protected] Abstract. Robert Burns is a well-known Scottish poet and his poem A Red Red Rose prevails all over the world. This essay will first make a brief introduction of Robert Burns and make an analysis of A Red Red Rose in the aspects of language, imagery and rhetoric. Keywords: Robert Burns; A Red Red Rose; language; imagery; rhetoric. 1. Robert Burns’ Life Experience Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) is a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is one of the most famous poets of Scotland and is widely regarded as a Scottish national poet. Being considered as a pioneer of the Romantic Movement, Robert Burns became a great source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and socialism after his death. Most of his world-renowned works are written in a Scots dialect. And in the meantime, he produced a lot of poems in English. He was born in a peasant’s clay-built cottage, south of Ayr, in Alloway, South Ayrshire, Scotland in 1759 His father, William Burnes (1721–1784), is a self-educated tenant farmer from Dunnottar in the Mearns, and his mother, Agnes Broun (1732–1820), is the daughter of a Kirkoswald tenant farmer. Despite the poor soil and a heavy rent, his father still devoted his whole life to plough the land to support the whole family’s livelihood. -

The Prayer of Holy Willie

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications English Language and Literatures, Department of 7-7-2015 The rP ayer of Holy Willie: A canting, hypocritical, Kirk Elder Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/engl_facpub Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Publication Info Published in 2015. Introduction and editorial matter copyright (c) Patrick Scott nda Scottish Poetry Reprint Series, 2015. This Book is brought to you by the English Language and Literatures, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PRAYER OF HOLY WILLIE by ROBERT BURNS Scottish Poetry Reprints Series An occasional series edited by G. Ross Roy, 1970-1996 1. The Life and Death of the Piper of Kilbarchan, by Robert Semphill, edited by G. Ross Roy (Edinburgh: Tragara Press, 1970). 2. Peblis, to the Play, edited by A. M. Kinghorn (London: Quarto Press, 1974). 3. Archibald Cameron’s Lament, edited by G. Ross Roy (London: Quarto Press, 1977). 4. Tam o’ Shanter, A Tale, by Robert Burns, ed. By G. Ross Roy from the Afton Manuscript (London: Quarto Press, 1979). 5. Auld Lang Syne, by Robert Burns, edited by G. Ross Roy, music transcriptions by Laurel E. Thompson and Jonathan D. Ensiminger (Greenock: Black Pennell Press, 1984). 6. The Origin of Species, by Lord Neaves, ed. Patrick Scott (London: Quarto Press, 1986). 7. Robert Burns, A Poem, by Iain Crichton Smith (Edinburgh: Morning Star, 1996). -

A Poem Ne Ly Sprung in Fairvie

A Poem Ne ly Sprung in Fairvie by CLARK AYCOCK ave you ever sung “Auld Lang therefore able to write in the local Ayrshire Syne” on New Year’s Eve? dialect, as well as in “Standard” English. He Or have you ever uttered the wrote many romantic poems that are still phrase, when frustrated, “the recited and sung today, and some of us may best-laid schemes of mice and men…”? remember his songs more easily than we do Did you know that John Steinbeck’s classic his poetry. in a human book Of Mice and Men was based on a line Robert Burns infl uenced many other head, though I in a poem written “To a Mouse”... or that poets including Wordsworth, Coleridge have seen the most a Tam O’ Shanter cap was named aft er a distinguished men of my time.” and Shelley. Walter Scott was also a great A commemorative plate showing character in a poem by that name? And admirer and wrote this wonderful descrip- In the late 1700s, many Scots migrated did you know that singer and songwriter tion of Burns that provides us with a clear from the Piedmont into the mountains of Robert Burns in the center Bob Dylan said his biggest creative impression of the man. “His person was WNC, bringing with them their country's surrounded by characters from inspiration was the poem and song “A strong and robust; his manners rustic, not culture and craft and inherent connection his poems Red, Red Rose”? Yes, we are talking about clownish, a sort of dignifi ed plainness and with Burns. -

Burns Chronicle 1939

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1939 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Gatehouse-of-Fleet Burns Club The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE AND CLUB DIRECTORY INSTITUTED 1891 PUBLISHED ANNUALLY SECOND SERIES : VOLUME XIV THE BURNS FEDERATION KILMARNOCK 1 939 Price Three shillings "BURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISER "0 what a glorious sight, warm-reekin', rich I"-BURNS WAUGH'S SCOTCH HAGGIS Delicious-Appetising-Finely Flavoured. Made from a recipe that has no equal for Quality. A wholesome meal for the Family . On the menu of every · important Scottish function-St. Andrew's Day, Burns Anniversary, &c., &c.-at home and abroad. Per 1/4 lb. Also in hermetically sealed tins for export 1 lb. 2/· 2 lbs. 3/6 3 lbs. 5/· (plus post) AlwaJ'S book 7our orders earl7 for these dates ST. ANDREW'S DAY CHRISTMAS DAY November 30 December 25 HOGMANAY BURNS ANNIVERSARY December31 Janu&l'J' 25 Sole Molc:er Coolced In the model lcltchen1 at HaftllCOn GEORGE WAUGH 110 NICOLSON STREET, EDINBURGH, 8 SCOTLAND Telephone 42849 Telearam1 and Cables: "HAGGIS" "BURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISER NATIONAL BURNS MEMORIAL COTTAGE HOME$, 1 MAUCHLINE, AYRSHIRE. i In Memory of the Poet Burns '! for Deserving Old People . .. That greatest of benevolent Institutions established In honour' .. of Robert Burns." -611,.11011 Herald. I~ I I ~ There are now twenty modern comfortable houses for the benefit of deserving old folks. The site is an ideal one in the heart of the Burns Country.