From Critical Theory to Political Science: A.R.L. Gurland’S Project of Critical Political Science in Postwar Germany1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Key Texts and Contributions to a Critical Theory of Society

1 Introduction: Key Texts and Contributions to a Critical Theory of Society Beverley Best, Werner Bonefeld and Chris O’Kane The designation of the Frankfurt School as a known by sympathisers as ‘Café Marx’. It ‘critical theory’ originated in the United was the first Marxist research institute States. It goes back to two articles, one writ- attached to a German University. ten by Max Horkheimer and the other by Since the 1950s, ‘Frankfurt School’ criti- Herbert Marcuse, that were both published in cal theory has become an established, inter- Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung (later Studies nationally recognised ‘brand name’ in the in Philosophy and Social Science) in 1937.1 social and human sciences, which derives The Zeitschrift, published from 1932 to from its institutional association in the 1920s 1941, was the publishing organ of the and again since 1951 with the Institute Institute for Social Research. It gave coher- for Social Research in Frankfurt, (West) ence to what in fact was an internally diverse Germany. From this institutional perspec- and often disagreeing group of heterodox tive, it is the association with the Institute Marxists that hailed from a wide disciplinary that provides the basis for what is considered spectrum, including social psychology critical theory and who is considered to be a (Fromm, Marcuse, Horkheimer), political critical theorist. This Handbook works with economy and state formation (Pollock and and against its branded identification, concre- Neumann), law and constitutional theory tising as well as refuting it. (Kirchheimer, Neumann), political science We retain the moniker ‘Frankfurt School’ (Gurland, Neumann), philosophy and sociol- in the title to distinguish the character of its ogy (Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse), culture critical theory from other seemingly non- (Löwenthal, Adorno), musicology (Adorno), traditional approaches to society, including aesthetics (Adorno, Löwenthal, Marcuse) the positivist traditions of Marxist thought, and social technology (Gurland, Marcuse). -

Ruth Wolf - Rehfeldt

RUTH WOLF - REHFELDT PRESS SELECTION ARTFORUM OCTOBER / NOV 2020 for American culture as Black culture, telling open secrets about lives REVIEWS rendered both highly visible and unseen. In “Segregation in the South,” 1956, the first of two series featured in the show, Parks chronicled the racially divided Deep South. We see a family dressed in their elegant best—hats and dresses and starched white shirts—at a Nashville bus station under a sign reading colored BUENOS AIRES life in captivity; the work is timely in a moment characterized by pre- waiting room. Elsewhere, children dressed in fire-engine-red outfits ventative isolation and an urgent need for the social reinsertion of those queue for ice cream under the colored sign. An old white woman who’ve been imprisoned. Florencia Levy’s Tierra de ciervos (Deer “Pensar todo de nuevo” serves them. The store’s brick wall is painted blinding white. Color Land), 2017, is represented by a photograph of an artificial lake of ROLF ART whispers its punishing difference, with the injustice repeated so often— radioactive waste in northern China. Suspected of espionage, the art- white only, lots for colored—that it almost vanishes. The proliferation of online viewing rooms and live streaming since the ist was arrested for taking the picture; the second part of the work, Mr. and Mrs. Albert Thornton, Mobile, Alabama, another work global spread of Covid-19 has challenged us to rethink the time and accessible through a QR code, is made up of shaky footage of her from the series, shows an elderly couple sitting together on a velveteen space of the exhibition. -

8. Erich Fromm's Social-Psychological

RUDOLF SIEBERT 8. ERICH FROMM’S SOCIAL-PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORY OF RELIGION Toward the X-Experience and the City of Being INTRODUCTION1 This essay explores Erich Fromm’s social-psychological theory of religion, as X- experience and longing for the City of Being, as being informed by the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, Meister Eckhart as well as Georg W.F Hegel, Karl Marx, and Sigmund Freud. Its religious attitude constituted the very dynamic of Fromm’s writings, as well as of those of the other critical theorists of society, e.g. Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Leo Loewenthal, Herbert Marcuse, etc., It united them. It could only be expressed in poetical symbols: the X-experience; or the longing for the imageless, nameless, notionless utterly Other than the horror and terror of nature and history; or the yearning for perfect justice and unconditional love: that the murderer may not triumph over the innocent victim, at least not ultimately. Man begins to become man only with the awakening of this longing for the entirely Other, or the X-experience. This religious attitude aims as idology at the destruction of all idolatry. In the Near East –––––––––––––– 1 Editors’ note-The author’s use of Fromm’s concept of “x-experience” comes from this passage in his work: What we call the religious attitude is an x that is expressible only in poetic and visual symbols. This x experience has been articulated in various concepts which have varied in accordance with the social organization of a particular cultural period. In the Near East, x was expressed in the concept of a supreme tribal chief, or king, and thus „God” became the supreme concept of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, which were rooted in the social structures of that area. -

Otto Kirchheimer and Carl Schmitt After 1945.” Redescriptions: Political Thought, Conceptual History and Feminist Theory 24(1): 4–26

REDESCRIPTIONS Buchstein, Hubertus. 2021. “The Godfather of Left-Schmittianism? Political Thought, Conceptual History and Feminist Theory Otto Kirchheimer and Carl Schmitt after 1945.” Redescriptions: Political Thought, Conceptual History and Feminist Theory 24(1): 4–26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33134/rds.320 RESEARCH The Godfather of Left-Schmittianism? Otto Kirchheimer and Carl Schmitt after 1945 Hubertus Buchstein Greifswald University, DE [email protected] In the vast secondary literature on Carl Schmitt as well as on the Frankfurt School, the political and legal thinker Otto Kirchheimer is described as a forerunner of contemporary Left-Schmittianism. This view is sometimes expanded in the litera- ture to the personal relationship between Schmitt and Kirchheimer after 1945 as well. A closer look at Kirchheimer’s late work, at his unpublished correspondence with Schmitt, and at additional unpublished sources contradicts such an interpre- tation. In fact, Kirchheimer strongly attacked Schmittianism in German debates on constitutional theory after 1945. This article finally uncovers the extent to which Schmitt tried to instrumentalize his former doctoral student to pursue his political rehabilitation in the Federal Republic via the United States. Kirchheimer, however, took a firm stand against this attempt. In his defense of modern parliamentary democracy, Kirchheimer definitely sided with the political left of his times; but he did so without any flirtation with Schmittianism. Keywords: Otto Kirchheimer; Carl Schmitt; Left-Schmittianism; antisemitism; West German political and legal thought I. Introduction: Against Some Legends The work of Carl Schmitt (1888–1985) has become a point of reference for a growing number of contemporary political theorists on the left. -

Visual Arts in the Urban Environment in the German Democratic Republic: Formal, Theoretical and Functional Change, 1949–1980

Visual arts in the urban environment in the German Democratic Republic: formal, theoretical and functional change, 1949–1980 Jessica Jenkins Submitted: January 2014 This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in partial fulfilment of its requirements) at the Royal College of Art Copyright Statement This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Royal College of Art. This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research for private study, on the understanding that it is copyright material, and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. Author’s Declaration 1. During the period of registered study in which this thesis was prepared the author has not been registered for any other academic award or qualification. 2. The material included in this thesis has not been submitted wholly or in part for any academic award or qualification other than that for which it is now submitted. Acknowledgements I would like to thank the very many people and institutions who have supported me in this research. Firstly, thanks are due to my supervisors, Professor David Crowley and Professor Jeremy Aynsley at the Royal College of Art, for their expert guidance, moral support, and inspiration as incredibly knowledgeable and imaginative design historians. Without a generous AHRC doctoral award and an RCA bursary I would not have been been able to contemplate a project of this scope. Similarly, awards from the German History Society, the Design History Society, the German Historical Institute in Washington and the German Academic Exchange Service in London, as well as additional small bursaries from the AHRC have enabled me to extend my research both in time and geography. -

Helke Rausch

THEODOR-HEUSS-KOLLOQUIUM 2017 Liberalismus und Nationalsozialismus – eine Beziehungsgeschichte Helke Rausch Liberalismus und Nationalsozialismus bei Ernst Jäckh – liberaler Phoenix, Grenzgänger und atlantischer „Zivil-Apostel“ Momentaufnahme einer inszenierten Beziehungsgeschichte: Jäckh und Hitler in Berlin, April 1933 In seiner Eigenschaft als langjähriger Leiter der Deutschen Hochschule für Politik in Berlin 1920 bis 1933 kam Ernst Jäckh 1933 zu seinem unmittelbarsten Direktkontakt mit dem neu- en Regime und seinem „Führer“. Jäckh stand unter akutem Handlungsdruck, sich gegenüber den neuen Machthabern zu positionieren. Während er in seinen Memoiren und andernorts ein hagiographisches Bild von seiner eigenen Überlegenheit und Widerständigkeit im Um- gang mit Hitler zeichnete, demzufolge er phoenixgleich als standhaft liberaler Regimegegner dem Diktator entgegentrat,1 konnte er trotz dieser auf den Erhalt der Hochschule zielenden Unterredung seine Institution nicht halten. Wie auch immer Jäckhs Beziehungsstrategie ge- genüber dem NS Anfang 1933 ausgesehen haben mag, sein Kalkül schlug gründlich fehl. Er musste das übergriffige Regime gewähren lassen. Die offizielle Gleichschaltung der Hoch- schule zog sich zwar noch bis 1937 hin, bevor das Institut als Reichsanstalt firmieren und schließlich 1940 den „Auslandswissenschaften“ als dezidierten NS-Politikwissenschaften zu- geordnet werden sollte. 2 Schon zuvor aber löste Jäckh den Verein Deutsche Hochschule für Politik e.V. Ende April 1933 auf.3 These und Argument Die Symptomatik des Direktkontakts zwischen dem Liberalen Jäckh und der NS-Führung be- steht nicht so sehr in einem vordergründigen Lackmustest für Jäckhs liberalen Widerstands- 1 Jäckh tischte nach verschiedenen Seiten hin eine ominöse Widerstandsgeschichte auf. Die Sebstheroisierung in seinen Memoiren kippt fast zur Farce, vgl. etwa Ernst Jäckh: Weltsaat. Erlebtes und Erstrebtes, Stuttgart 1960, S. -

Mautner, Karl.Toc.Pdf

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project KARL F. MAUTNER Interviewed by: Thomas J. Dunnigan Initial interview date: May 12, 1993 opyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Austria Austrian Army 1 35-1 36 Emigrated to US 1 40 US Army, World War II Berlin 1 45-1 5, Divided Berlin Soviet Blockade and US Airlift .urrency Reform- Westmark Elections, 01 4,1 Federal Basic 2a3 and Berlin East vs. West Berlin Revolt in East Berlin With Brandt and Other Personalities Bureau of .ultural Affairs - State Department 1 5,-1 61 European E5change Program Officer Berlin Task Force 1 61-1 65 Berlin Wall 6ice President 7ohnson8s visit to Berlin 9hartoum, Sudan 1 63-1 65 .hief of political Section Sudan8s North-South Rivalry .oup d8etat Department of State, Detailed to NASA 1 65 Negotiating Facilities Abroad Retirement 1 General .omments of .areer INTERVIEW %: Karl, my first (uestion to you is, give me your background. I understand that you were born in Austria and that you were engaged in what I would call political work from your early days and that you were active in opposition to the Na,is. ould you tell us something about that- MAUTNER: Well, that is an oversimplification. I 3as born on the 1st of February 1 15 in 6ienna and 3orked there, 3ent to school there, 3as a very poor student, and joined the Austrian army in 1 35 for a year. In 1 36 I got a job as accountant in a printing firm. I certainly couldn8t call myself an active opposition participant after the Anschluss. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2c73n9k4 Author Boyle, Michael Shane Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence By Michael Shane Boyle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair Professor Anton Kaes Professor Shannon Steen Fall 2012 The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence © Michael Shane Boyle All Rights Reserved, 2012 Abstract The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance After the Age of Affluence by Michael Shane Boyle Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair While much humanities scholarship focuses on the consequence of late capitalism’s cultural logic for artistic production and cultural consumption, this dissertation asks us to consider how the restructuring of capital accumulation in the postwar period similarly shaped activist practices in West Germany. From within the fields of theater and performance studies, “The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence” approaches this question historically. It surveys the types of performance that decolonization and New Left movements in 1960s West Germany used to engage reconfigurations in the global labor process and the emergence of anti-imperialist struggles internationally, from documentary drama and happenings to direct action tactics like street blockades and building occupations. -

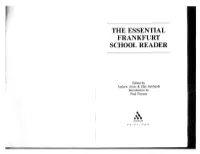

Erich Fromm, "The Method and Function of Analytic Social

THE ESSENTIAL FRANKFURT SCHOOL READER Edited by Andrew Arato & Eike Gebhardt Introduction by Paul Piccone continuum NEW YORK.."LONDON I Contents 2005 The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc 15 East 26 Street, New York, NY 10010 The Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd The Tower Building, 11 York Road, London SEI 7NX Preface vii Copyright © 1982 by The Continuum Publishing Company General Introduction Paul Piccone ix All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means; electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, Part I Political Sociology and or otherwise, without the written permission of Critique of Politics The Continuum Publishing Company. Printed in the United States of America Introducticn by Andrew Arato 3 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data The End of Reason Max Horkheimer 26 Main entry under title: Changes in the Structure of The Essential Frankfurt school reader. Political Compromise Otto Kirchheimer 49 Originally published. New York: Urizen Books, State Capitalism: Its Possibilities cl978. Bibliography: p. and Limitations Friedrich Pollock 71 Includes index. The Authoritarian State Max Horkheimer 95 1. Mass society-Addresses, essays, lectures. Freudian Theory and the Pattern 2. Political science-Addresses, essays, lectures. 3. Economics-Addresses, 'essays, lectures. 'of Fascist Propaganda TheDdor W. Adorno 118 4. Social sciences-Methodology-Addresses, essays, Some Social Implications of lectures. I. Arata, Andrew. II. Gebhardt, Eike, Herbert Marcuse 138 III. Title: Frankfurt school reader. Modem Technology HMlOl.E745 1982 300 82-8063 Notes 163 ISBN 0-8264-0194-5 AACR2 476 A Critique of Methodology recognizes the.historical subject in its sinngebendeLeistung;but then, by suspending, bracketing it, the phenomenological analysis creates its own a priori, its own ideation, and its own ideological veil. -

The Controversy Over Friedrich Pollock's State Capitalism

Article History of the Human Sciences 2016, Vol. 29(2) 23–41 The controversy over ª The Author(s) 2016 Reprints and permission: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Friedrich Pollock’s state DOI: 10.1177/0952695116637296 capitalism hhs.sagepub.com Manfred Gangl University of Applied Studies, Germany Abstract The critique of capitalism is the bedrock on which rests the reputation of Frankfurt School critical theory. Though critical theory has often been heralded – or criticized and rejected – as a reformulation of Marxian theory for our times, its relation with the critique of political economy, and in particular the economic treatises, has barely been studied. Friedrich Pollock, who was Max Horkheimer’s lifelong friend and close associate at the Institute for Social Research, was responsible for all administrative and financial questions, but he wrote few theoretical essays and Wiggershaus calls him ‘the last unknown member of the Frankfurt School’. Nevertheless this article asks whether not only has his influence on early critical theory been sorely underestimated, but also his impact on the late philosophies of Horkheimer, Adorno and Marcuse. Keywords critical theory, critique of political economy, dialectic of enlightenment, Friedrich Pollock, state capitalism The reputation of Frankfurt School critical theory rests upon its critique of capitalism. It has often been heralded – or criticized and rejected – as a reformulation of Marxian theory for our times. Yet the relation between critical theory and the critique of political economy has barely been studied, least of all its economic treatises. Friedrich Pollock, Max Horkheimer’s lifelong friend and close associate at the Insti- tute for Social Research,1 where he was responsible for all administrative and financial Corresponding author: Manfred Gangl, Hochschule Fulda – University of Applied Studies, Leipziger Str. -

Has the Afd Changed German Politics?

2/2017 2/2017 Has the AfD changed German politics? Klaus Ziemer Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University in Warsaw Abstract The entry of the AfD to the Bundestag marks a new stage in German politics. This article traces the origins of this right-wing populist party against the background of extreme right- wing parties in post-war Germany. It analyses the main precepts of the party’s programme and its activity in parliaments on the regional (Länder) level. A look at where AfD-voters are coming from reveals a long-term trend of a weakening alignment between voters and parties and a growing fragmentation of the German party system. Key words AfD, origins, party programme, AfD electorate, parliamentary activity he political scene in Germany is in a state of flux. The elections Tto the Bundestag in 2017 have, in a most remarkable way, con- tinued the long-term change of the German party system. The entry of the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany, AfD) reflects the changes in the political cleavages in Germany after the immigration crisis of 2015 and has brought about the end of unam- biguous coalition alternatives on the federal level. The loss of votes by most of the established parties (the SPD got its worst result in Bundestag elections ever) and the number of parliamentary groups: six, which the Bundestag had last seen in 1953 – has made it clear that the Federal Republic is entering a new stage in its history. This was confirmed by the fact that the formation of a new government took half a year – an un- precedented long period of time in the history of the Federal Republic.