Clemency for Faln Members Hearings Committee on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aurea María Sotomayor Miletti

Aurea María Sotomayor-Miletti (Writer and Professor) University of Pittsburgh Department of Hispanic Languages and Literatures [email protected] [email protected] Education: 5/ 2008 –– Juris Doctor. School of Law, University of Puerto Rico. Cum Laude. 9/1976-8/1980—Ph.D. Stanford University, Stanford, California. Department of Spanish and Portuguese. 8/1974-8/1976.—M. A. Indiana University. Bloomington, Department of Comparative Literature. 8/1968/-5/1972.— B. A. University of Puerto Rico. Magna Cum Laude. Employment History: 1-2011-Professor. Hispanic Languages and Literatures. University of Pittsburgh. 8-1998-12/1999. Acting Chair. Department of Spanish. University of Puerto Rico (Main Campus). 8-1994-12/ 2010. Professor. Department of Spanish. University of Puerto Rico. 8/1989- 7/1994. Associate Professor, Department of Spanish. UPR (Main Campus). 1/1986-7/1989. Assistant Professor, Department of Spanish. UPR (Main Campus). 8/1980-5/1983. Assistant Professor, Interamerican University (Main Campus), Dept. of Spanish. 8/1977-6/1980. Stanford University. Teaching Assistant, Department of Spanish. 1978-1979. Research Assistant to Prof. Jean Franco, Stanford University. Areas of Interest: Caribbean Literature, Poetry and Poetics, Women and Gender Studies, Law and Literature, Violence, Human Rights and Environmental Issues in Contemporary Latin American Literature, Puerto Rican Literature. Foreign Languages: Spanish (native-speaker), English, French and Italian (excellent reading knowledge, oral comprehension), Portuguese (reading knowledge and oral comprehension), Latin and German (some). Dissertations and papers: 8/1980 —Ph.D. Stanford University (Department of Spanish and Portuguese), The Parameters of Narration in Macedonio Fernández. Director: Prof. Jean Franco. Dissertation committee: Prof. Mary Louise Pratt and Prof. -

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

A Case Study on the Fuerzas Armadas De Liberación Nacional (FALN)

Effects and effectiveness of law enforcement intelligence measures to counter homegrown terrorism: A case study on the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN) Final Report to the Science & Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security August 2012 National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence Based at the University of Maryland 3300 Symons Hall • College Park, MD 20742 • 301.405.6600 • www.start.umd.edu National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence About This Report The author of this report is Roberta Belli of John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York. Questions about this report should be directed to Dr. Belli at [email protected]. This report is part of a series sponsored by the Human Factors/Behavioral Sciences Division, Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, in support of the Prevent/Deter program. The goal of this program is to sponsor research that will aid the intelligence and law enforcement communities in identifying potential terrorist threats and support policymakers in developing prevention efforts. This research was supported through Grant Award Number 2 009ST108LR0003 made to the START Consortium and the University of Maryland under principal investigator Gary LaFree. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security or START. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

FALN-Memo.Pdf

- 0- NAME DATE THERESA MELLON 5-2/-47 TITLE SUPERVISORY ARCHIVES SPECIALIST NAME AND ADDRESS OF DEPOSITORY NARA - Office of Regional Records Services 200 Space Center Drive Lee's Summit, MO 64064 . I The ATTORNEY certifies that he will make satisfactory arrangements with the court reporter for payment of the cost of the transcript. (FRAP 10(b)) ,Method of payment u Funds u CJA Form 21 DATE signature Prepared by courtroom deputy To be completed by Court Reponer and b COURT REPORTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENT forwarded to Court of Appeals. Date order received Estimated completion date Estimated number of pages. Date Signature (Court Reporter) NOTICE -OF APPEAL UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT United States of Arcerica Docket Numwr CR-83--00025 :* 1 b !. -vs- i: Charles P, sigtpp E D*. Julio Xosado, Andres Rosado, (District Cqp(t@&tx'S !:iFF\Lt Ricardo Xomero, Steven Guerra G. S. ~~.-,-RI:~.TcOtlR'T E.D.N-** and Maria Cueto * JUNIS,~* T,pAE A.bJ...@k ?..------------- Maria Cueto p.M ...... --.--- Notice is hereby given that ----appe& to :I ' the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from the & J order Iother 2d (specify 1 entered in this action on (Date) Elizabeth Fink, Esq, (Counsel for Appellant) Feb. 18, 1983 Address Date To : 383 Pearl St. Brooklyn, N.Y. 11201 Phone Number 624-0800 ADD ADDITIONAL PAGE IF NECESSARY BE COMPLETED BY ATTORNEY) TRANSCRIPT INFORMATION - FORM B DESCRIPTION OF PROCEEDINGS FOR WHICH TRANSCRIPT IS QUESTIONNAIRE TRANSCRIPT ORDER 'REQUIRED (INCLUDE DATE). n ordering a transcript Prepare transcript of Dates n not ordering a transcript U Pre-trial proceedings Reason: u rial u Daily copy is available uSentence u U.S. -

Almanaque Marc Emery. June, 2009

CONTENIDOS 2CÁLCULOS ASTRONÓMICOS PARA LOS PRESOS POLÍTICOS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS EN EL AÑO 2009. Jan Susler. 6ENERO. 11 LAS FASES DE LA LUNA EN LA AGRICULTURA TRADICIONAL. José Rivera Rojas. 15 FEBRERO. 19ALIMÉNTATE CON NUESTROS SUPER ALIMENTOS SILVESTRES. María Benedetti. 25MARZO. 30EL SUEÑO DE DON PACO.Minga de Cielos. 37 ABRIL. 42EXTRACTO DE SON CIMARRÓN POR ADOLFINA VILLANUEVA. Edwin Reyes. 46PREDICCIONES Y CONSEJOS. Elsie La Gitana. 49MAYO. 53PUERTO RICO: PARAÍSO TROPICAL DE LOS TRANSGÉNICOS. Carmelo Ruiz Marrero. 57JUNIO. 62PLAZA LAS AMÉRICAS: ENSAMBLAJE DE IMÁGENES EN EL TIEMPO. Javier Román. 69JULIO. 74MACHUCA Y EL MAR. Dulce Yanomamo. 84LISTADO DE ORGANIZACIONES AMBIENTALES EN PUERTO RICO. 87AGOSTO. 1 92SOBRE LA PARTERÍA. ENTREVISTA A VANESSA CALDARI. Carolina Caycedo. 101SEPTIEMBRE. 105USANDO LAS PLANTAS Y LA NATURALEZA PARA POTENCIAR LA REVOLUCIÓN CONSCIENTE DEL PUEBLO.Marc Emery. 110OCTUBRE. 114LA GRAN MENTIRA. ENTREVISTA AL MOVIMIENTO INDÍGENA JÍBARO BORICUA.Canela Romero. 126NOVIEMBRE. 131MAPA CULTURAL DE 81 SOCIEDADES. Inglehart y Welzel. 132INFORMACIÓN Y ESTADÍSTICAS GENERALES DE PUERTO RICO. 136DICIEMBRE. 141LISTADO DE FERIAS, FESTIVALES, FIESTAS, BIENALES Y EVENTOS CULTURALES Y FOLKLÓRICOS EN PUERTO RICO Y EL MUNDO. 145CALENDARIO LUNAR Y DÍAS FESTIVOS PARA PUERTO RICO. 146ÍNDICE DE IMÁGENES. 148MAPA DE PUERTO RICO EN BLANCO PARA ANOTACIONES. 2 3 CÁLCULOS ASTRONÓMICOS PARA LOS PRESOS Febrero: Memorias torrenciales inundarán la isla en el primer aniversario de la captura de POLÍTICOS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS EN EL AÑO 2009 Avelino González Claudio, y en el tercer aniversario de que el FBI allanara los hogares y oficinas de independentistas y agrediera a periodistas que cubrían los eventos. Preparado por Jan Susler exclusivamente para el Almanaque Marc Emery ___________________________________________________________________ Marzo: Se predice lluvias de cartas en apoyo a la petición de libertad bajo palabra por parte de Carlos Alberto Torres. -

La Diáspora Puertorriqueña: Un Legado De Compromiso the Puerto Rican Diaspora: a Legacy of Commitment

Original drawing for the Puerto Rican Family Monument, Hartford, CT. Jose Buscaglia Guillermety, pen and ink, 30 X 30, 1999. La Diáspora Puertorriqueña: Un Legado de Compromiso The Puerto Rican Diaspora: A Legacy of Commitment P uerto R ican H eritage M o n t h N ovember 2014 CALENDAR JOURNAL ASPIRA of NY ■ Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños ■ El Museo del Barrio ■ El Puente Eugenio María de Hostos Community College, CUNY ■ Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly La Casa de la Herencia Cultural Puertorriqueña ■ La Fundación Nacional para la Cultura Popular, PR LatinoJustice – PRLDEF ■ Música de Camara ■ National Institute for Latino Policy National Conference of Puerto Rican Women – NACOPRW National Congress for Puerto Rican Rights – Justice Committee Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration www.comitenoviembre.org *with Colgate® Optic White® Toothpaste, Mouthwash, and Toothbrush + Whitening Pen, use as directed. Use Mouthwash prior to Optic White® Whitening Pen. For best results, continue routine as directed. COMITÉ NOVIEMBRE Would Like To Extend Is Sincerest Gratitude To The Sponsors And Supporters Of Puerto Rican Heritage Month 2014 City University of New York Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly Colgate-Palmolive Company Puerto Rico Convention Bureau The Nieves Gunn Charitable Fund Embassy Suites Hotel & Casino, Isla Verde, PR Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center American Airlines John Calderon Rums of Puerto Rico United Federation of Teachers Hotel la Concha Compañia de Turismo de Puerto Rico Hotel Copamarina Acacia Network Omni Hotels & Resorts Carlos D. Nazario, Jr. Banco Popular de Puerto Rico Dolores Batista Shape Magazine Hostos Community College, CUNY MEMBER AGENCIES ASPIRA of New York Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños El Museo del Barrio El Puente Eugenio María de Hostos Community College/CUNY Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly La Casa de la Herencia Cultural Puertorriqueña, Inc. -

Senado De Puerto Rico Diario De Sesiones Procedimientos Y Debates De La Decimocuarta Asamblea Legislativa Septima Sesion Ordinaria Año 2004 Vol

SENADO DE PUERTO RICO DIARIO DE SESIONES PROCEDIMIENTOS Y DEBATES DE LA DECIMOCUARTA ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA SEPTIMA SESION ORDINARIA AÑO 2004 VOL. LII San Juan, Puerto Rico Miércoles, 23 de junio de 2004 Núm. 61 A las doce y treinta y tres minutos de la tarde (12:33 p.m.) de este día, miércoles, 23 de junio de 2004, el Senado inicia sus trabajos bajo la Presidencia del señor Rafael Rodríguez Vargas, Presidente Accidental. ASISTENCIA Señores: Modesto L. Agosto Alicea, Luz Z. Arce Ferrer, Eudaldo Báez Galib, Norma Burgos Andújar, Juan A. Cancel Alegría, Norma Carranza De León, José Luis Dalmau Santiago, Antonio J. Fas Alzamora, Velda González de Modestti, Sixto Hernández Serrano, Rafael Luis Irizarry Cruz, Pablo Lafontaine Rodríguez, Fernando J. Martín García, Kenneth McClintock Hernández, Yasmín Mejías Lugo, José Alfredo Ortiz Daliot, Margarita Ostolaza Bey, Migdalia Padilla Alvelo, Orlando Parga Figueroa, Sergio Peña Clos, Roberto L. Prats Palerm, Miriam J. Ramírez, Bruno A. Ramos Olivera, Jorge A. Ramos Vélez, Julio R. Rodríguez Gómez, Angel M. Rodríguez Otero, Cirilo Tirado Rivera, Roberto Vigoreaux Lorenzana y Rafael Rodríguez Vargas, Presidente Accidental. PRES. ACC. (SR. RODRIGUEZ VARGAS): Hoy, 23 de junio de 2004, a las doce y treinta y tres (12:33) del día, se reanudan los trabajos. INVOCACION El Diácono José A. Morales, miembro del Cuerpo de Capellanes del Senado de Puerto Rico, procede con la Invocación: DIACONO MORALES: Buenas tardes a todos. Leemos de la Carta del Apóstol San Pedro, la Primera Carta del Apóstol San Pedro: “Sed humildes unos con otros porque Dios resiste a los soberbios, pero da su gracia a los humildes. -

Clinton Presidential Records in Response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Requests Listed in Attachment A

VIA EMAIL (LM 2019-054) April 9, 2019 The Honorable Pat A. Cipollone Counsel to the President The White House Washington, D.C. 20502 Dear Mr. Cipollone: In accordance with the requirements of the Presidential Records Act (PRA), as amended, 44 U.S.C. §§2201-2209, this letter constitutes a formal notice from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to the incumbent President of our intent to open Clinton Presidential records in response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests listed in Attachment A. These records, consisting of 115,212 pages, have been reviewed for all applicable FOIA exemptions, resulting in 10,243 pages restricted in whole or in part. NARA is proposing to open the remaining 104,969 pages. A copy of any records proposed for release under this notice will be provided to you upon your request. We are also concurrently informing former President Clinton’s representative, Bruce Lindsey, of our intent to release these records. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a), NARA will release the records 60 working days from the date of this letter, which is July 3, 2019, unless the former or incumbent President requests a one-time extension of an additional 30 working days or asserts a constitutionally based privilege, in accordance with 44 U.S.C. 2208(b)-(d). Please let us know if you are able to complete your review before the expiration of the 60 working day period. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a)(1)(B), we will make this notice available to the public on the NARA website. -

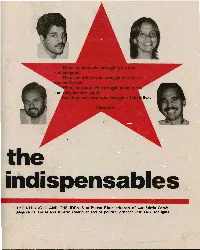

Indispensables

There are men who struggle for a day and are good There are others who struggle for a year and are better There are those who struggle many years hey are very good ^^^ m 11 th A lives These are... the indispensables THE STRUGGLE AND THE IDEALS of Puerto Rican prisoners of war Edwin Cortes, Alejandrina Torres and Alberto Rodriguez and of political prisoner Jos6 Luis Rodriguez "...all the childre the world an the reason I will i to the death to destroy colonialism... This publication is dedicated to the future of our homeland and to the children of the three new Puerto Rican Prisoners of War, Liza Beth and Catalina Torres; Yazmfn Elena and Ricardo Alberto Rodriguez; and Noemi and Cark>s Alberto Cortes. —Alberto R Cover; prose by Bertolt Brecht Editorial El Coquf 1671 N. Claremont (312) 342-8023/4 AUTOBIOGRAPHIES Chicago, Illinois 60647 OF THE 4 "...all the children of the world are the reason I will fight to the death to destroy colonialism..." This publication is dedicated to the future of our homeland and to the children of the three new Puerto Rican Prisoners of War, Liza Beth and Catalina Torres; Yazmfn Elena and Ricardo Alberto Rodriguez; and Noemf and Carlps Alberto Cortes. —Alberto Rodriguez olt Brecht Editorial El Coqui' 1671 N. Claremont (312) 342-8023/4 AUTOBIOGRAPHIES Chicago, Illinois 60647 OF THE 4 • ALBERTO RODRIGUEZ I...reaffirm the right of the Puerto Rican people to wage armed struggle against U.S. imperialism." I was born in Bronx, New York on April and we walked out. -

Warfare in the American Homeland: Policing and Prison in a Penal

WARFARE IN THE AMERICAN HOMELAND WARFARE IN THE AMERICAN HOMELAND POLICING AND PRISON IN A PENAL DEMOCRACY Edited by Joy James Duke University Press Durham and London 2007 © 2007 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Acknowledgments for previously printed material and cred- its for illustrations appear at the end of this book. TO: OGGUN AND OSHUN Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. —THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT, SECTION 1, U.S. CONSTITUTION As a slave, the social phenomenon that engages my whole consciousness is, of course, revolution. —GEORGE JACKSON Contents Preface: The American Archipelago xi Acknowledgments xix Introduction: Violations 3 joy james I. Insurgent Knowledge 1. The Prison Slave as Hegemony’s (Silent) Scandal 23 frank b. wilderson iii 2. Forced Passages 35 dylan rodríguez 3. Sorrow: The Good Soldier and the Good Woman 58 joy james 4. War Within: A Prison Interview 76 dhoruba bin wahad 5. Domestic Warfare: A Dialogue 98 marshall eddie conway 6. Soledad Brother and Blood in My Eye (Excerpts) 122 george jackson 7. The Masked Assassination 140 michel foucault, catherine von bülow, daniel defert translation and introduction by sirène harb 8. A Century of Colonialism: One Hundred Years of Puerto Rican Resistance 161 oscar lópez rivera II. -

Imprescindibles

Hay hombres que ischan on y son buenos Hay otres que luchah un ano y son mejores Hay ouienss luchan muchos anos y soa muy buenos Bl s que luchan toda la vida Esos son... imprescindibles LUCHA E IDEARIO de los prisioneros de guerra puertorriquenos Edwin Cortes, Alejandrina Torres y Alberto Rodrfguez y del prisionero politico Jose Luis Rodnguez 44 P< ha destru Esta obra esta dedicada al future de nuestra patria y a los ninos de los tres nuevos Prisioneros de Guerra Puertorriquefios, Liza Beth y Catalina Torres; Yazmfn Elena y Ricardo Alberto Rodriguez; y Noerm y Carlos Alberto Cortes. Portada: pensamiento por Bertolt Brecht Editorial El Coqui 1671 N. Claremont (312) 342-8023/4 Chicago, Illinois 60647 "...todos los ninos del mundo son la razon por la cual luchare hasta la muerte para destruir el colonialismo..." —Alberto Rodrfguez AUTOBIOGRAFIAS DE LOS 4 ALBERTO RODRIGUEZ ...yo reafirmo el derecho del pueblo puertorriqueno de luchar y librar guerra contra el imperialismo estadounidense.'' Yo nacf el 14 de abril de 1953, en el de Chicago. barrio puertorriqueno conocido como el Participe en mi primer acto poli'tico a la Bronx en Nueva York. Debido a ladeprimida edad de quince anos. Los estudiantes afro- economia colonial y a la represion lanzada americanos en la escuela superior donde yo contra la clase trabajadora, mis padres, asistfa, Tilden Tech, habfan planificado una Manuel Rodriguez y Carmen Santana, habi'an huelga masiva en protesta del asesinato del sido forzados a dejar su querido Puerto Rico. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. El liderato estu- Antes de mi primer cumpleanos, mi familia diantil afro-americano habi'a pedido el apoyo se mudo de Nueva York a Chicago.