A Case Study on the Fuerzas Armadas De Liberación Nacional (FALN)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colecciones Especiales De Bibliotecas De La Universidad De Puerto Rico

Colecciones Especiales de Bibliotecas de la Universidad de Puerto Rico Volumen 2 Colecciones Especiales de Bibliotecas de la Universidad de Puerto Rico Volumen 2 Colecciones Especiales de Bibliotecas de la Universidad de Puerto Rico Volumen 2 Coordinadora Esther Villarino Tur Editores Hilda R. Hernández Rivera León Santos Orozco José A. Pérez Pelay Esther Villarino Tur Iraida Ríos Arroyo Introducción José A. Robledo González Autores Aura Díaz López Edwin Ríos Cruz Marinilda Fuentes Sánchez Osvaldo Rivera Soto Rosalind E. Irizarry Martínez Robert Rosado Quiñones Miguel Ángel Náter Gustavo Salvarrey Iranzo Jorge I. Ortiz Malavé Miguel A. Santiago Rivera San Juan, Puerto Rico 2021 Diseño y diagramación por Esther Villarino Tur Cubierta frontal y posterior por Esther Villarino Tur basada en el diseño original creado por Luis Alberto Aponte Valderas para Colecciones Especiales de Bibliotecas de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, volumen 1, 2017 Logo CPDCC-UPR por Alex Colón Hernández Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra sin previo permiso escrito por parte de sus autores. Edición, 2021 ISBN 978-0-578-92830-2 © Universidad de Puerto Rico Contenido Miembros de la Comunidad de Práctica Desarrollo Colaborativo de Colecciones de la Universidad de Puerto Rico (CPDCC-UPR) ........................................................................................ i Introducción José A. Robledo González ..................................................................................................... ii UPR en Aguadilla Sala Aguadillana -

Aurea María Sotomayor Miletti

Aurea María Sotomayor-Miletti (Writer and Professor) University of Pittsburgh Department of Hispanic Languages and Literatures [email protected] [email protected] Education: 5/ 2008 –– Juris Doctor. School of Law, University of Puerto Rico. Cum Laude. 9/1976-8/1980—Ph.D. Stanford University, Stanford, California. Department of Spanish and Portuguese. 8/1974-8/1976.—M. A. Indiana University. Bloomington, Department of Comparative Literature. 8/1968/-5/1972.— B. A. University of Puerto Rico. Magna Cum Laude. Employment History: 1-2011-Professor. Hispanic Languages and Literatures. University of Pittsburgh. 8-1998-12/1999. Acting Chair. Department of Spanish. University of Puerto Rico (Main Campus). 8-1994-12/ 2010. Professor. Department of Spanish. University of Puerto Rico. 8/1989- 7/1994. Associate Professor, Department of Spanish. UPR (Main Campus). 1/1986-7/1989. Assistant Professor, Department of Spanish. UPR (Main Campus). 8/1980-5/1983. Assistant Professor, Interamerican University (Main Campus), Dept. of Spanish. 8/1977-6/1980. Stanford University. Teaching Assistant, Department of Spanish. 1978-1979. Research Assistant to Prof. Jean Franco, Stanford University. Areas of Interest: Caribbean Literature, Poetry and Poetics, Women and Gender Studies, Law and Literature, Violence, Human Rights and Environmental Issues in Contemporary Latin American Literature, Puerto Rican Literature. Foreign Languages: Spanish (native-speaker), English, French and Italian (excellent reading knowledge, oral comprehension), Portuguese (reading knowledge and oral comprehension), Latin and German (some). Dissertations and papers: 8/1980 —Ph.D. Stanford University (Department of Spanish and Portuguese), The Parameters of Narration in Macedonio Fernández. Director: Prof. Jean Franco. Dissertation committee: Prof. Mary Louise Pratt and Prof. -

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

Rafael Cancel-Miranda Praised on His 90Th Birthday

Rafael Cancel-Miranda praised on his 90th birthday Mayagüez, July 19 (RHC)-- A group of independence fighters on Saturday exalted the figure of nationalist fighter Rafael Cancel-Miranda, on his 90th birthday, at the Vivaldi Cemetery in Mayagüez, where his remains have been laid to rest since March 8th. Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP) leader Julio Muriente Perez lamented that due to his irredeemable death, on July 18th he could not be shared with thousands of his fellow countrymen in his native Mayaguez, in western Puerto Rico, "where his immortal remains now rest." The former president of the Movimiento Independentista Nacional Hostosiano (MINH) said that perhaps the meeting would have been at the grave of the combative nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos, in the cemetery of Old San Juan, where Cancel-Miranda first went after stepping on Puerto Rican soil after his release from prison in September 1979, after spending 25 years in U.S. prisons. Muriente Pérez said that on this occasion "we would have liked to sing to him, recite his poems, remember his anecdotes, laugh at his great sense of humor, re-charge his batteries with his immeasurable desire to live and serve his people and humanity, evoke his admirable perseverance and firmness of principle." Likewise, he said, we would have remembered, with similar respect to his colleagues Oscar Collazo, Lolita Lebron, Irving Flores and Andres Figueroa Cordero, that "like Rafaelito they are our National Heroes." Born on July 18, 1930 in Mayagüez, he dedicated his life to the independence of Puerto Rico under the inspiration of Pedro Albizu Campos, whom as a Cadet of the Republic, a youth organization of the Nationalist Party, he welcomed in December 1947 upon his return from serving a 10-year sentence in Atlanta and New York charged with conspiracy to overthrow the United States government. -

Ron Reagan Does Not Consider Himself an Activist

Photoshop # White Escaping from my Top winners named ‘Nothing Fails father’s Westboro in People of Color Like Prayer’ contest Baptist Church student essay contest winners announced PAGES 10-11 PAGE 12-16 PAGE 18 Vol. 37 No. 9 Published by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Inc. November 2020 Supreme Court now taken over by Christian Nationalists President Trump’s newly confirmed Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett is going to be a disaster for the constitutional prin- ciple of separation between state and church and will complete the Christian Nationalist takeover of the high court for more than a generation, the Freedom From Religion Foundation asserts. Barrett’s biography and writings reveal a startling, life-long allegiance to religion over the law. The 48-year-old Roman Catholic at- tended a Catholic high school and a Presby- terian-affiliated college and then graduated from Notre Dame Law School, where she Photo by David Ryder taught for 15 years. She clerked for archcon- Amy Coney Barrett Despite his many public statements on atheism, Ron Reagan does not consider himself an activist. servative Justice Antonin Scalia, and signifi- cantly, like the late justice, is considered an “originalist” or “textual- ist” who insists on applying what is claimed to be the “original intent” of the framers. She and her parents have belonged to a fringe con- servative Christian group, People of Praise, which teaches that hus- Ron Reagan — A leading bands are the heads of household. Barrett’s nomination hearing for a judgeship on the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, where she has served for less than three years, documented her many controversial figure of nonbelievers and disturbing positions on religion vis-à-vis the law. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

FALN-Memo.Pdf

- 0- NAME DATE THERESA MELLON 5-2/-47 TITLE SUPERVISORY ARCHIVES SPECIALIST NAME AND ADDRESS OF DEPOSITORY NARA - Office of Regional Records Services 200 Space Center Drive Lee's Summit, MO 64064 . I The ATTORNEY certifies that he will make satisfactory arrangements with the court reporter for payment of the cost of the transcript. (FRAP 10(b)) ,Method of payment u Funds u CJA Form 21 DATE signature Prepared by courtroom deputy To be completed by Court Reponer and b COURT REPORTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENT forwarded to Court of Appeals. Date order received Estimated completion date Estimated number of pages. Date Signature (Court Reporter) NOTICE -OF APPEAL UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT United States of Arcerica Docket Numwr CR-83--00025 :* 1 b !. -vs- i: Charles P, sigtpp E D*. Julio Xosado, Andres Rosado, (District Cqp(t@&tx'S !:iFF\Lt Ricardo Xomero, Steven Guerra G. S. ~~.-,-RI:~.TcOtlR'T E.D.N-** and Maria Cueto * JUNIS,~* T,pAE A.bJ...@k ?..------------- Maria Cueto p.M ...... --.--- Notice is hereby given that ----appe& to :I ' the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from the & J order Iother 2d (specify 1 entered in this action on (Date) Elizabeth Fink, Esq, (Counsel for Appellant) Feb. 18, 1983 Address Date To : 383 Pearl St. Brooklyn, N.Y. 11201 Phone Number 624-0800 ADD ADDITIONAL PAGE IF NECESSARY BE COMPLETED BY ATTORNEY) TRANSCRIPT INFORMATION - FORM B DESCRIPTION OF PROCEEDINGS FOR WHICH TRANSCRIPT IS QUESTIONNAIRE TRANSCRIPT ORDER 'REQUIRED (INCLUDE DATE). n ordering a transcript Prepare transcript of Dates n not ordering a transcript U Pre-trial proceedings Reason: u rial u Daily copy is available uSentence u U.S. -

Almanaque Marc Emery. June, 2009

CONTENIDOS 2CÁLCULOS ASTRONÓMICOS PARA LOS PRESOS POLÍTICOS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS EN EL AÑO 2009. Jan Susler. 6ENERO. 11 LAS FASES DE LA LUNA EN LA AGRICULTURA TRADICIONAL. José Rivera Rojas. 15 FEBRERO. 19ALIMÉNTATE CON NUESTROS SUPER ALIMENTOS SILVESTRES. María Benedetti. 25MARZO. 30EL SUEÑO DE DON PACO.Minga de Cielos. 37 ABRIL. 42EXTRACTO DE SON CIMARRÓN POR ADOLFINA VILLANUEVA. Edwin Reyes. 46PREDICCIONES Y CONSEJOS. Elsie La Gitana. 49MAYO. 53PUERTO RICO: PARAÍSO TROPICAL DE LOS TRANSGÉNICOS. Carmelo Ruiz Marrero. 57JUNIO. 62PLAZA LAS AMÉRICAS: ENSAMBLAJE DE IMÁGENES EN EL TIEMPO. Javier Román. 69JULIO. 74MACHUCA Y EL MAR. Dulce Yanomamo. 84LISTADO DE ORGANIZACIONES AMBIENTALES EN PUERTO RICO. 87AGOSTO. 1 92SOBRE LA PARTERÍA. ENTREVISTA A VANESSA CALDARI. Carolina Caycedo. 101SEPTIEMBRE. 105USANDO LAS PLANTAS Y LA NATURALEZA PARA POTENCIAR LA REVOLUCIÓN CONSCIENTE DEL PUEBLO.Marc Emery. 110OCTUBRE. 114LA GRAN MENTIRA. ENTREVISTA AL MOVIMIENTO INDÍGENA JÍBARO BORICUA.Canela Romero. 126NOVIEMBRE. 131MAPA CULTURAL DE 81 SOCIEDADES. Inglehart y Welzel. 132INFORMACIÓN Y ESTADÍSTICAS GENERALES DE PUERTO RICO. 136DICIEMBRE. 141LISTADO DE FERIAS, FESTIVALES, FIESTAS, BIENALES Y EVENTOS CULTURALES Y FOLKLÓRICOS EN PUERTO RICO Y EL MUNDO. 145CALENDARIO LUNAR Y DÍAS FESTIVOS PARA PUERTO RICO. 146ÍNDICE DE IMÁGENES. 148MAPA DE PUERTO RICO EN BLANCO PARA ANOTACIONES. 2 3 CÁLCULOS ASTRONÓMICOS PARA LOS PRESOS Febrero: Memorias torrenciales inundarán la isla en el primer aniversario de la captura de POLÍTICOS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS EN EL AÑO 2009 Avelino González Claudio, y en el tercer aniversario de que el FBI allanara los hogares y oficinas de independentistas y agrediera a periodistas que cubrían los eventos. Preparado por Jan Susler exclusivamente para el Almanaque Marc Emery ___________________________________________________________________ Marzo: Se predice lluvias de cartas en apoyo a la petición de libertad bajo palabra por parte de Carlos Alberto Torres. -

La Diáspora Puertorriqueña: Un Legado De Compromiso the Puerto Rican Diaspora: a Legacy of Commitment

Original drawing for the Puerto Rican Family Monument, Hartford, CT. Jose Buscaglia Guillermety, pen and ink, 30 X 30, 1999. La Diáspora Puertorriqueña: Un Legado de Compromiso The Puerto Rican Diaspora: A Legacy of Commitment P uerto R ican H eritage M o n t h N ovember 2014 CALENDAR JOURNAL ASPIRA of NY ■ Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños ■ El Museo del Barrio ■ El Puente Eugenio María de Hostos Community College, CUNY ■ Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly La Casa de la Herencia Cultural Puertorriqueña ■ La Fundación Nacional para la Cultura Popular, PR LatinoJustice – PRLDEF ■ Música de Camara ■ National Institute for Latino Policy National Conference of Puerto Rican Women – NACOPRW National Congress for Puerto Rican Rights – Justice Committee Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration www.comitenoviembre.org *with Colgate® Optic White® Toothpaste, Mouthwash, and Toothbrush + Whitening Pen, use as directed. Use Mouthwash prior to Optic White® Whitening Pen. For best results, continue routine as directed. COMITÉ NOVIEMBRE Would Like To Extend Is Sincerest Gratitude To The Sponsors And Supporters Of Puerto Rican Heritage Month 2014 City University of New York Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly Colgate-Palmolive Company Puerto Rico Convention Bureau The Nieves Gunn Charitable Fund Embassy Suites Hotel & Casino, Isla Verde, PR Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center American Airlines John Calderon Rums of Puerto Rico United Federation of Teachers Hotel la Concha Compañia de Turismo de Puerto Rico Hotel Copamarina Acacia Network Omni Hotels & Resorts Carlos D. Nazario, Jr. Banco Popular de Puerto Rico Dolores Batista Shape Magazine Hostos Community College, CUNY MEMBER AGENCIES ASPIRA of New York Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños El Museo del Barrio El Puente Eugenio María de Hostos Community College/CUNY Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly La Casa de la Herencia Cultural Puertorriqueña, Inc. -

Senado De Puerto Rico Diario De Sesiones Procedimientos Y Debates De La Decimocuarta Asamblea Legislativa Septima Sesion Ordinaria Año 2004 Vol

SENADO DE PUERTO RICO DIARIO DE SESIONES PROCEDIMIENTOS Y DEBATES DE LA DECIMOCUARTA ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA SEPTIMA SESION ORDINARIA AÑO 2004 VOL. LII San Juan, Puerto Rico Miércoles, 23 de junio de 2004 Núm. 61 A las doce y treinta y tres minutos de la tarde (12:33 p.m.) de este día, miércoles, 23 de junio de 2004, el Senado inicia sus trabajos bajo la Presidencia del señor Rafael Rodríguez Vargas, Presidente Accidental. ASISTENCIA Señores: Modesto L. Agosto Alicea, Luz Z. Arce Ferrer, Eudaldo Báez Galib, Norma Burgos Andújar, Juan A. Cancel Alegría, Norma Carranza De León, José Luis Dalmau Santiago, Antonio J. Fas Alzamora, Velda González de Modestti, Sixto Hernández Serrano, Rafael Luis Irizarry Cruz, Pablo Lafontaine Rodríguez, Fernando J. Martín García, Kenneth McClintock Hernández, Yasmín Mejías Lugo, José Alfredo Ortiz Daliot, Margarita Ostolaza Bey, Migdalia Padilla Alvelo, Orlando Parga Figueroa, Sergio Peña Clos, Roberto L. Prats Palerm, Miriam J. Ramírez, Bruno A. Ramos Olivera, Jorge A. Ramos Vélez, Julio R. Rodríguez Gómez, Angel M. Rodríguez Otero, Cirilo Tirado Rivera, Roberto Vigoreaux Lorenzana y Rafael Rodríguez Vargas, Presidente Accidental. PRES. ACC. (SR. RODRIGUEZ VARGAS): Hoy, 23 de junio de 2004, a las doce y treinta y tres (12:33) del día, se reanudan los trabajos. INVOCACION El Diácono José A. Morales, miembro del Cuerpo de Capellanes del Senado de Puerto Rico, procede con la Invocación: DIACONO MORALES: Buenas tardes a todos. Leemos de la Carta del Apóstol San Pedro, la Primera Carta del Apóstol San Pedro: “Sed humildes unos con otros porque Dios resiste a los soberbios, pero da su gracia a los humildes. -

Clinton Presidential Records in Response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Requests Listed in Attachment A

VIA EMAIL (LM 2019-054) April 9, 2019 The Honorable Pat A. Cipollone Counsel to the President The White House Washington, D.C. 20502 Dear Mr. Cipollone: In accordance with the requirements of the Presidential Records Act (PRA), as amended, 44 U.S.C. §§2201-2209, this letter constitutes a formal notice from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to the incumbent President of our intent to open Clinton Presidential records in response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests listed in Attachment A. These records, consisting of 115,212 pages, have been reviewed for all applicable FOIA exemptions, resulting in 10,243 pages restricted in whole or in part. NARA is proposing to open the remaining 104,969 pages. A copy of any records proposed for release under this notice will be provided to you upon your request. We are also concurrently informing former President Clinton’s representative, Bruce Lindsey, of our intent to release these records. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a), NARA will release the records 60 working days from the date of this letter, which is July 3, 2019, unless the former or incumbent President requests a one-time extension of an additional 30 working days or asserts a constitutionally based privilege, in accordance with 44 U.S.C. 2208(b)-(d). Please let us know if you are able to complete your review before the expiration of the 60 working day period. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a)(1)(B), we will make this notice available to the public on the NARA website. -

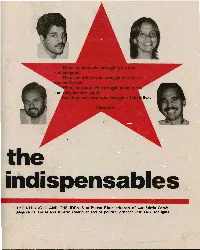

Indispensables

There are men who struggle for a day and are good There are others who struggle for a year and are better There are those who struggle many years hey are very good ^^^ m 11 th A lives These are... the indispensables THE STRUGGLE AND THE IDEALS of Puerto Rican prisoners of war Edwin Cortes, Alejandrina Torres and Alberto Rodriguez and of political prisoner Jos6 Luis Rodriguez "...all the childre the world an the reason I will i to the death to destroy colonialism... This publication is dedicated to the future of our homeland and to the children of the three new Puerto Rican Prisoners of War, Liza Beth and Catalina Torres; Yazmfn Elena and Ricardo Alberto Rodriguez; and Noemi and Cark>s Alberto Cortes. —Alberto R Cover; prose by Bertolt Brecht Editorial El Coquf 1671 N. Claremont (312) 342-8023/4 AUTOBIOGRAPHIES Chicago, Illinois 60647 OF THE 4 "...all the children of the world are the reason I will fight to the death to destroy colonialism..." This publication is dedicated to the future of our homeland and to the children of the three new Puerto Rican Prisoners of War, Liza Beth and Catalina Torres; Yazmfn Elena and Ricardo Alberto Rodriguez; and Noemf and Carlps Alberto Cortes. —Alberto Rodriguez olt Brecht Editorial El Coqui' 1671 N. Claremont (312) 342-8023/4 AUTOBIOGRAPHIES Chicago, Illinois 60647 OF THE 4 • ALBERTO RODRIGUEZ I...reaffirm the right of the Puerto Rican people to wage armed struggle against U.S. imperialism." I was born in Bronx, New York on April and we walked out.