EC247 Slaughtering Hogs and Cutting Pork on the Farm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Adoption of Genetic Modification in Pork Production Chains

Analysis of adoption of genetic modification in pork production chains PROMOTOR Prof. dr. ir. R.B.M. Huirne Hoogleraar Agrarische Bedrijfseconomie Wageningen Universiteit CO-PROMOTOREN Dr. ir. M.P.M. Meuwissen Senior onderzoeker bij Institute for Risk Management in Agriculture (IRMA) en Universitair docent bij de leerstoelgroep Bedrijfseconomie Wageningen Universiteit Dr. I.A.C.M. van der Lans Universitair docent bij de leerstoelgroep Marktkunde en Consumentengedrag Wageningen Universiteit SAMENSTELLING PROMOTIECOMMISSIE Prof. dr. ir. W. Verbeke Universiteit Gent, Belgi Dr.ir. G.B.C. Backus Landbouw Economisch Instituut, Den Haag Prof. dr. ir. L.A. den Hartog Wageningen Universiteit Prof.dr.ir. J.A.M. van Arendonk Wageningen Universiteit Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de Mansholt Graduate School of Social Sciences Tatiana A. Novoselova Analysis of adoption of genetic modification in pork production chains Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 8 juni 2007 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula Analysis of adoption of genetic modification in pork production chains PhD-thesis Wageningen University – with references – with summaries in English and Dutch Novoselova T.A., 2007 ISBN: 978-90-8504-666-0 Abstract During the past decades the agro-food sector has changed and developed due to the impact of new emerging technologies. Genetic modification (GM) presents one of the recently widely- discussed new technologies. The main objective of this study was to gain insight into adoption of genetic modification in the pork production chain. The project covered three important stages of the chain: the farrowing and fattening stages and the consumers. -

Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards a PROGRAM for the RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK

Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK This section is organized in the following order: SELECT AN AREA TO VIEW IT Species Cuts Chart LARGER SEE THE Species-Specific FOLLOWING Primal Information AREAS Index of Cuts Cut Nomenclature PORK -- Increasing in and U.P.C.Numbers Popularity Figure 1-- Primal (Wholesale) Cuts and Bone Structure of Pork Figure 2 -- Loin Roasts -- Center Chops INTRODUCTION Figure 3 -- Portion Pieces APPROVED NAMES -- Center Chops BEEF Figure 4-- Whole or Half Loins VEAL PORK Figure 5 -- Center Loin or Strip Loin LAMB GROUND MEATS Pork Belly EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT & Pork Leg FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY Pork Cuts GLOSSARY & REFERENCES Approved by the National Pork Board INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF VEAL PORK LAMB GROUND MEATS EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY GLOSSARY & REFERENCES INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF VEAL PORK LAMB GROUND MEATS EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY GLOSSARY & REFERENCES INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF -

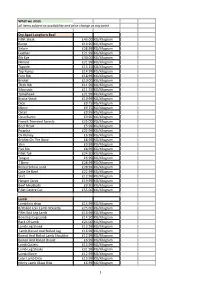

What We Stock All Items Subject to Availability and Price Change at Any Point

What we stock all items subject to availability and price change at any point Dry Aged Longhorn Beef Fillet Steak £45.00 KG/Kilogram Rump £19.95 KG/Kilogram Sirloin £28.99 KG/Kilogram Feather £21.99 KG/Kilogram Rib Eye £30.00 KG/Kilogram Minute £21.99 KG/Kilogram Topside £13.15 KG/Kilogram Top Rump £14.99 KG/Kilogram Fore Rib £18.99 KG/Kilogram Brisket £10.00 KG/Kilogram Thick Rib £11.99 KG/Kilogram Silverside £11.55 KG/Kilogram Tomahawk £21.99 KG/Kilogram Braise Steak £10.99 KG/Kilogram Dice £9.75 KG/Kilogram Mince £9.75 KG/Kilogram Oxtail £9.95 KG/Kilogram Osso Bucco £9.95 KG/Kilogram French Trimmed Forerib £25.00 KG/Kilogram Beef Heart £5.99 KG/Kilogram Picanha £22.99 KG/Kilogram Ox Kidney £6.99 KG/Kilogram Brisket On The Bone £8.99 KG/Kilogram Shin £9.99 KG/Kilogram Flat Rib £8.99 KG/Kilogram Fillet Tail £24.50 KG/Kilogram Tongue £6.99 KG/Kilogram T Bone £28.99 KG/Kilogram Rolled Sirloin Joint £28.99 KG/Kilogram Cote De Beof £22.99 KG/Kilogram Skirt £12.99 KG/Kilogram Hanger Steak £19.99 KG/Kilogram Beef Meatballs £9.50 KG/Kilogram Fillet Centre Cut £55.00 KG/Kilogram Lamb Lamb loin chop £14.99 KG/Kilogram B/Rolled Loin Lamb NoiseWe £25.00 KG/Kilogram Fillet End Leg Lamb £16.99 KG/Kilogram Boneless Leg Lamb £14.50 KG/Kilogram Rack Of Lamb £24.00 KG/Kilogram Lamb Leg Shank £13.99 KG/Kilogram Lamb Boned And Rolled Leg £16.99 KG/Kilogram Boned And Rolled Lamb Shoulder £12.99 KG/Kilogram Boned And Rolled Breast £6.99 KG/Kilogram Lamb Cutlets £13.99 KG/Kilogram Lamb Leg Steaks £21.99 KG/Kilogram Lamb Mince £12.99 KG/Kilogram Lean Lamb Dice -

Black Angus Meats

PRST STD US POSTAGE PAID BUFFALO NY BLACKBLACK ANGUSANGUS PERMIT #3438 MEATS & SEAFOOD 2519 Niagara Falls Boulevard Amherst, NY 14228 (691-4554) Fill Your Freezer With Ask For Details your Tax Returns Free Delivery Available Visit us on the web @ bameats.com FREE Family Fish Fry CASH Daily 3lbs Beer Battered Haddock CREDIT Delivery 5lbs Straight Cut French Fries Call 2lbs Cole Slaw EBT Mon. - Sat. ACCEPTED 9:00-7:00 691-4554 $29.99 Basic Pack After School Special 2lbs Boneless Chicken Breast 12ct Hot Pockets (pizza) 2lbs Country Style Ribs 8ct Mama Rosa’s Mini Pizzas 2lbs Pepper Steak $79 Springtime Specials 3lbs Lean Ground Beef 5lbs Chicken Fingers 3lbs Split Chicken Breast 2lbs Chicken Nuggets 3lbs Chicken Legs and Thighs 2lbs Chicken Patties 2lbs Center Cut Pork Chops 4lbs Chicken Wings 5lbs French Fries 5ct Banquet Pot Pies 6ct Corn Dogs Winter Freezer Filler 6ct Beef & Bean Burrito 2lbs New York Strip Steak 2lbs Tater Tots 2lbs Boneless Wings 5lbs French Fries 3lbs Lean Ground Beef Cabbage 12ct Pizza Logs $149 Corned Beef 3lbs Smoked Polish Sausage Brisket $.69 lb 3lbs Boneless Breast Points $3.49lb 3lbs Chicken Thighs Kids Snack Pack Flats 4.99lb Kids Snack Pack 3lbs Pork Roast $139 2lbs Cube Steaks 5lbs Chicken Fingers Italian Sausage 3lbs Chicken Sausage 8ct Mama Rosa’s Mini Pizza Smoked Neck Bones 5lbs Chicken Drumsticks 3lbs Chicken Nuggets 5lbs French Fries 3bs Chicken Patties 12ct Pizza Logs $89 Butcher Shop Special 4lbs Chicken Wings 2lbs New York Strip Steak 2lbs Seasoned Curly Fries 2lbs Boneless Breast $2.99 lb $1.99 -

Order Form | Meat Department Product Name Inserts (650) | South

120 ____ BEEF PLATE BOILING BEEF 221 ____ BEEF ROUND STEAK BONELESS 121 ____ BEEF PLATE SHORT RIBS 222 ____ BEEF ROUND SIRLOIN TIP STEAK 000 ____ BEEF CHUCK ARM POT ROAST 122 ____ BEEF PLATE SPARERIBS 223 ____ BEEF ROUND TOP ROUND STEAK 001 ____ BEEF CHUCK ARM POT ROAST 123 ____ BEEF PLATE SKIRT STEAK 224 ____ BEEF ROUND BOTTOM ROUND STEAK BONELESS 124 ____ BEEF PLATE SKIRT STEAK CUBED 225 ____ BEEF ROUND EYE ROUND STEAK 002 ____ BEEF CHUCK ROUND BONE ROAST 125 ____ ROLLED BEEF PLATE BONELESS 226 ____ BEEF ROUND SWISS STEAK BONELESS 003 ____ BEEF CHUCK ROUND BONE POT ROAST 130 ____ BEEF FLANK STEAK 227 ____ BEEF ROUND TOP ROUND 004 ____ BEEF CHUCK SHOULDER ROAST LONDON BROIL 131 ____ BEEF FLANK STEAK CUBED 005 ____ BEEF CHUCK SHOULDER POT ROAST 240 ____ GROUND BEEF BONELESS 132 ____ ROLLED BEEF FLANK STEAK CUBED DOES NOT EXCEED 30% FAT 006 ____ BEEF CHUCK CLOD ROAST 133 ____ BEEF FLANK STEAK ROLLS 134 ____ BEEF FLANK LONDON BROIL 241 ____ LEAN GROUND BEEF 006-1 ____ BEEF CHUCK SHOULDER CLOD ROAST DOES NOT EXCEED 22% FAT BONELESS 140 ____ BEEF RIB ROAST 242 ____ LEANEST GROUND BEEF 007 ____ BEEF CHUCK 7- BONE ROAST 143 ____ BEEF RIB EYE ROAST DOES NOT EXCEED 15% FAT 008 ____ BEEF CHUCK BLADE ROAST 144 ____ BEEF RIB SPENCER ROAST BONELESS 243 ____ CHILI GROUND BEEF 009 ____ BEEF CHUCK TOP BLADE POT ROAST 150 ____ BEEF RIB STEAK 250 ____ BONELESS BEEF STEW 020 ____ BEEF CHUCK ROAST BONELESS 153 ____ BEEF RIB EYE STEAK 251 ____ BEEF HEARTS 021 ____ BEEF CHUCK CROSS RIB POT ROAST 153-1 ____ BEEF RIB RIB EYE STEAK BONE-IN 252 ____ BEEF MARROW -

4Generations

www.McDonaldsMeats.com Clear Lake, Minnesota Full-Service Meat Counter Meat Full-Service GENERATIONS Beef Steaks Ribeye Steak Turkey since 1914 Bone-In Ribeye Steak Ground Beef 2012 GRAND CHAMPION 4 Quantity Discounts Available on Ground Beef New York Strip Steak SMOKED TURKEY T-Bone Steak 85% Lean Ground Beef Special Cuts Boneless Turkey Breast Fillets 93% Extra Lean Ground Beef Lemon Peppered Boneless Turkey Breast As a USDA inspected facility, we are committed to offering quality products and Porterhouse Steak Tenderloin Steak 85% Locally Raised Lean Ground Beef Fillets exceptional customer service. Through four generations, we’ve kept our dedication Top Sirloin Steak Ground Beef Patties Ground Turkey to quality and service. Today, our meat market features a full-service meat counter, Ball Tip Steak Mushroom & Onion Ground Beef Patties Ground Turkey Patties special cuts, as well as homemade sausages and our world-famous jerky. Mac’s Seasoned Sirloin Steak Mushroom & Swiss Ground Beef Patties Pork Stuffed Turkey Rolls Montreal Seasoned Steak Wild Rice Ground Beef Patties Pork Chops Frozen Turkeys Visit our online store at Flat Iron Steak Bacon Ground Beef Patties Thick Cut Pork Chops McDonaldsMeats.com Jalapeno Cheddar Ground Beef Patties BBQ Seasoned Pork Chops GIFT CARDS available Round Steak Chicken Visa, Master Card, Discover, American Flank Steak Pizza Burgers Teriyaki Pork Chops Cut-Up Chicken Fryers Express and EBT cards accepted! Chuck Eye Steak BBQ Bacon Cheeseburger Patties Boneless Pork Chops Home Grown Chickens We process all types of Greek Seasoned Skirt Steak Black & Bleu Burgers Pork Roast Boneless Chicken Breast wild game all year long. -

Factors Affecting U.S. Pork Consumption/LDP-M-130-01 Economic Research Service/USDA Introduction

Electronic Outlook Report from the Economic Research Service United States Department www.ers.usda.gov of Agriculture Factors Affecting U.S. LDP-M-130-01 Pork Consumption May 2005 Christopher G. Davis and Biing-Hwan Lin Abstract Pork ranks third in annual U.S. meat consumption, behind beef and chicken, averaging 51 pounds per person. The Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII) indicates that most pork is consumed at home. Pork consumption is highest in the Midwest (58 pounds), followed by the South (52 pounds), the Northeast (51 pounds), and the West (42 pounds). Rural consumers eat more pork (60 pounds) than urban/suburban consumers (49/48 pounds). Pork consumption varies by race and ethnicity. Blacks consume 63 pounds of pork per person per year, Whites 49 pounds, and Hispanics 45 pounds. Higher income consumers tend to consume less pork. Everything else remaining constant, demographic data in the CSFII suggest future declines in per capita pork consumption, as increases of Hispanics and the elderly—who eat less pork than the national average—enlarge their shares of the population. However, total U.S. pork consumption will grow because of an expansion of the U.S. population. Keywords: Pork, consumption, fresh pork, processed pork, per capita use, ethnicity, region, gender, age, income. Acknowledgments The authors thank the following individuals for their insightful comments: Janet Perry, Donald Blayney, William Hahn, Joy Harwood, Gary Lucier, LaVerne Creek, and Lewrene Glaser, all of ERS; Jeffrey Gillespie, Louisiana State University; John Lawrence, Iowa State University; Steve Meyer, Paragon Economics; and Shayle Shagam, World Agricultural Outlook Board. -

Pork Order Guide

Pork B U L K P U R C H A S I N G G U I D E B E N T A R R O W A C R E S Thank you! YOUR PURCHASE OF A WHOLE OR HALF PIG MEANS SO MUCH TO OUR FARM. WE IN THIS GUIDE: LOVE THE PIGS WE RAISE AND THE EXCELLENT PORK THEY PROVIDE. WE HOW WE DO IT CANNOT WAIT FOR YOU AND YOUR - WHAT IS PASTURE RAISED? - PRICING AND MORE FAMILY TO ENJOY IT AS WELL! CUTS OF PORK THIS GUIDE WILL HELP YOU - UNDERSTAND THE UNDERSTAND THE FEW THINGS THAT ANATOMY AND PLACE YOUR NEED TO BE DONE TO ENSURE YOU ORDER BASED ON HAVE THE BEST EXPERIENCE WITH PREFERENCES YOUR BULK PORK PURCHASE. PREPARE FOR DELIVERY FREEZER SIZES AND WHAT WE ARE ALWAYS HERE IF YOU HAVE TO EXPECT ANY QUESTIONS, SO DON'T HESITATE EATING AND ENJOYING YOUR TO GET IN TOUCH! PORK - MEAL PLANNING AND FINDING RECIPES LOVE, THE TROST'S How Pigs live at Bent Arrow Acres We chose to raise pigs because, after a lot of research, we found all the good they can do for the land if properly maintained… and because bacon. But, over the years, we have learned to love them and feel that they are really interesting animals. They chase our cars and love to come say "Hi!" when we are out in the yard. Let us know if you would ever like to come see them too! BENT ARROW PORK QUICK FACTS: WE RAISE BERKSHIRE PORK. -

Marketing Niche Pork

PORK: MARKETING ALTERNATIVES MARKETING AND BUSINESS GUIDE National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service www.attra.ncat.org Abstract: This publication suggests that sustainable hog producers consider alternative marketing approaches for their pork. Sustainable hog producers are creating products that many consumers can’t find in their grocery stores, but want to buy. Consumers perceive sustainably raised pork to be healthier to eat. They are willing to pay hog producers more for raising pigs in a manner that is humane, helps sustain family farms, and is more environmentally friendly than conventional production methods. Direct marketing and niche markets are among the alternative marketing strategies discussed. Legal considerations, labels, trademarks, processing regulations, and obstacles are addressed. Sources of additional information are also provided. By Lance Gegner NCAT Agriculture Specialist Related ATTRA publications April 2004 ©2004 NCAT • Considerations in Organic Hog Production Table of Contents • Sustainable Hog Production Overview • Profitable Pork: Strategies for Pork Introduction................................. 1 Producers (SAN publication) Commodity vs. Niche • Alternative Meat Marketing Marketing ................................. 2 • Direct Marketing What Is Direct Marketing? ....... 2 • Farmers’ Markets Where Are the Niche Markets? .................................... 3 Introduction Niche Marketing Opportunities ........................... 4 Successful marketing is a necessary part of any Niche Marketing With -

Smith and Sons Meat Processing Custom Butchering, Processing, and Retail Meat Corner 5080 E

Smith and Sons Meat Processing Custom Butchering, Processing, and Retail Meat Corner 5080 E. Broadway Mt. Pleasant, MI 48858 (989) 772 6048 Store Hours: Mon-Fri 9-5:30 Sat 9-2:00 www.smithandsonsmeatprocessing.com 1. Bundle Price $95.00 2. Bundle Price $92.00 3. Bundle Price $108.00 4. Bundle Price $115.00 5. Bundle Price $155.00 5# Beef Roast 8# Spare Rib 5# Pork Steak 5# Beef Roast 10# Ground Beef 5# Ground Beef 5# Pork Steak 5# Pork Chops 5# Chuck or Denver Steak 5# Frozen Mixed Steaks 5# Pork Steak 5# Pork Chops 5# Country Style Ribs 5# Pork Steak 5# Bacon 5# Bacon 5# Ground Beef 5# Link Sausage 10# Ground Beef 4# Hot Dogs 5# Chicken Leg Quarters 5# Chicken Leg Quarters 5# Bacon 5# Chicken Leg Quarters 5# Chicken Leg Quarters 1 Whole Chicken 1 Whole Chicken 5# Chicken Leg Quarters 1 Whole Chicken 3# Chicken Breast 1 Whole Chicken 1 Whole Chicken 6. Bundle Price $172.00 7. Bundle Price $175.00 8. Bundle Price $208.00 9. Bundle Price $270.00 10. Bundle Price $48.00 5# Beef Roast 5# Pork Steak 5# Rib-Eye Steak 10# Beef Roast 4# Hamburger Patties 5# Frozen Mixed Steaks 5# Pork Chops 10# Chuck Steaks 5# Pork Steak 4# Hot Dogs 10# Ground Beef 5# Beef Roast 5# Denver Steaks 10# Frozen Mixed Steaks 2#Bacon 5# Bacon 5# Chuck Steak 5# Beef Roast 10# Ground Beef 5# Link Sausage 5# Sirloin Steak 10# Ground Beef 5# Link Sausage 3# Chicken Breast 10# Ground Beef 5# Bacon 5# Chicken Leg Quarters 4# Hot Dogs 1 Whole Chicken 5# Chicken Leg Quarters 1 Whole Chicken All Items are frozen and pre-packaged. -

Meats Irish Beef

MEATS IRISH BEEF Beef Carvery Rib Bone-In Beef Short Rib (Jacobs Ladder) Dried-Aged Cote de Boeuf Weight /Quantity 5.8kg Weight /Quantity 6.5kg Weight /Quantity 1kg x 5 Price Unit : KILO Price Unit : KILO Price Unit : KILO PRICE: €11.90 £10.12 PRICE: €7.90 £6.72 PRICE: €13.80 £11.73 CODE: 18307 CODE: 18069 CODE: 18222 Beef Cube Roll (Feirme Nádúrtha) Beef Cube Roll Beef Chuck Roll Weight /Quantity 3kg Weight /Quantity 3kg Weight /Quantity 3kg Price Unit : KILO Price Unit : KILO Price Unit : KILO PRICE: €25.90 £22.02 PRICE: €18.90 £16.07 PRICE: €7.85 £6.68 CODE: 18277 CODE: 18150 CODE: 18114 Beef Rib-Eye Steak Larder-Trim Beef Rib-Eye Steak Larder-Trim Beef Rib-Eye Steak Larder-Trim Weight /Quantity 198g (7oz) Weight /Quantity 227g (8oz) Weight /Quantity 255g (9oz) Price Unit : EACH Price Unit : EACH Price Unit : EACH PRICE: €4.55 £3.87 PRICE: €5.20 £4.42 PRICE: €5.85 £4.98 CODE: 18234 CODE: 18121 CODE: 18129 Beef Rib Eye Steak (Feirme Nádúrtha) 7oz Beef Rib Eye Steak (Feirme Nádúrtha) Beef Rib Eye Steak (Feirme Nádúrtha) 9oz Weight /Quantity 198g (7oz) Weight /Quantity 227g (8oz) Weight /Quantity 255g (9oz) Price Unit : EACH Price Unit : EACH Price Unit : EACH PRICE: €5.53 £4.71 PRICE: €6.32 £5.38 PRICE: €7.10 £6.04 CODE: 18278 CODE: 18279 CODE: 18280 PRICES ARE SUBJECT TO FLUCTUATION DUBLIN | TEL : +353 16234111 | FAX : +353 1 6234042 | BELFAST | TEL : 028 90432522 | FAX : 028 90950055 [email protected] 11 11 MEATS MEATS IRISH BEEF IRISH BEEF Beef Striploin Bone-On (Feirme Nádúrtha) Beef Striploin Bone-On Beef T-Bone Short-Loin -

Pridgeon Appointed to Commission of Agriculture in Memory of MPPA

2017, VOL. 42, NO. 1 MICHIGAN Michigan’s Pork Producers source for information. Pg. 12 Pg. 15 Pg. 22 Pridgeon appointed In Memory of MPPA to Commission MPPA board member Scholarships of Agriculture Bob Bloomer Awarded mmarch2017mag.inddarch2017mag.indd 1 44/7/2017/7/2017 12:05:0712:05:07 PMPM MANAGING FARM STRESS WORKSHOP WHEN: April 17, 2017 10am-2pm Lunch included WHERE: Van Buren ISD Conference Center 490 South Paw Paw Street, Lawrence, MI 49064. MSU Extension has developed a workshop specially designed COST: FREE for people who work with agricultural producers and farm families who want to know more about managing farm-related stress and learn ways to approach and communicate with those MUST RSVP: in need. https://events.anr.msu.edu/ The workshop will include: farmersunderstress_vanburen/ x Adam Kantrovich discussing the present agricultural market situation with an overview of how this has affected a farm’s Farmers and those financial situation and cash flow. within the agricultural x Roger Betz discussing his experiences working with farm families industry have a that are under financial distress. x Suzanne Pish highlighting the detrimental impact of stress on our tendency to be eternal body and state of mind, providing information on how to optimists, but with all recognize some of the warning signs of depression, self-harm of the variability in and mental illness. agriculture, there are For more information visit: times when we can msue.anr.msu.edu/managingfarmstress become overwhelmed MSU is an affirmative-action, equal-opportunity employer, committed to achieving excellence through a diverse workforce and inclusive culture that encourages all people to reach their full potential.