Grasshopper Integrated Pest Management User Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 3 Life Cycles of Insects

Praying Mantis 3A-1 Hi, boys and girls. It’s time to meet one of the most fascinating insects on the planet. That’s me. I’m a praying mantis, named for the way I hold my two front legs together as though I am praying. I might look like I am praying, but my incredibly fast front legs are designed to grab my food in the blink of an eye! Praying Mantis 3A-1 I’m here to talk to you about the life stages of insects—how insects develop from birth to adult. Many insects undergo a complete change in shape and appearance. I’m sure that you are already familiar with how a caterpillar changes into a butterfly. The name of the process in which a caterpillar changes, or morphs, into a butterfly is called metamorphosis. Life Cycle of a Butterfly 3A-2 Insects like the butterfly pass through four stages in their life cycles: egg, larva [LAR-vah], pupa, and adult. Each stage looks completely different from the next. The young never resemble, or look like, their parents and almost always eat something entirely different. Life Cycle of a Butterfly 3A-2 The female insect lays her eggs on a host plant. When the eggs hatch, the larvae [LAR-vee] that emerge look like worms. Different names are given to different insects in this worm- like stage, and for the butterfly, the larva state is called a caterpillar. Insect larvae: maggot, grub and caterpillar3A-3 Fly larvae are called maggots; beetle larvae are called grubs; and the larvae of butterflies and moths, as you just heard, are called caterpillars. -

Wax, Wings, and Swarms: Insects and Their Products As Art Media

Wax, Wings, and Swarms: Insects and their Products as Art Media Barrett Anthony Klein Pupating Lab Biology Department, University of Wisconsin—La Crosse, La Crosse, WI 54601 email: [email protected] When citing this paper, please use the following: Klein BA. Submitted. Wax, Wings, and Swarms: Insects and their Products as Art Media. Annu. Rev. Entom. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-ento-020821-060803 Keywords art, cochineal, cultural entomology, ethnoentomology, insect media art, silk 1 Abstract Every facet of human culture is in some way affected by our abundant, diverse insect neighbors. Our relationship with insects has been on display throughout the history of art, sometimes explicitly, but frequently in inconspicuous ways. This is because artists can depict insects overtly, but they can also allude to insects conceptually, or use insect products in a purely utilitarian manner. Insects themselves can serve as art media, and artists have explored or exploited insects for their products (silk, wax, honey, propolis, carmine, shellac, nest paper), body parts (e.g., wings), and whole bodies (dead, alive, individually, or as collectives). This review surveys insects and their products used as media in the visual arts, and considers the untapped potential for artistic exploration of media derived from insects. The history, value, and ethics of “insect media art” are topics relevant at a time when the natural world is at unprecedented risk. INTRODUCTION The value of studying cultural entomology and insect art No review of human culture would be complete without art, and no review of art would be complete without the inclusion of insects. Cultural entomology, a field of study formalized in 1980 (43), and ambitiously reviewed 35 years ago by Charles Hogue (44), clearly illustrates that artists have an inordinate fondness for insects. -

Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815)

Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815) Pierre-Etienne Stockland Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2017 Etienne Stockland All rights reserved ABSTRACT Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815) Pierre-Etienne Stockland Naturalists, state administrators and farmers in France and its colonies developed a myriad set of techniques over the course of the long eighteenth century to manage the circulation of useful and harmful insects. The development of normative protocols for classifying, depicting and observing insects provided a set of common tools and techniques for identifying and tracking useful and harmful insects across great distances. Administrative techniques for containing the movement of harmful insects such as quarantine, grain processing and fumigation developed at the intersection of science and statecraft, through the collaborative efforts of diplomats, state administrators, naturalists and chemical practitioners. The introduction of insectivorous animals into French colonies besieged by harmful insects was envisioned as strategy for restoring providential balance within environments suffering from human-induced disequilibria. Naturalists, administrators, and agricultural improvers also collaborated in projects to maximize the production of useful substances secreted by insects, namely silk, dyes and medicines. A study of -

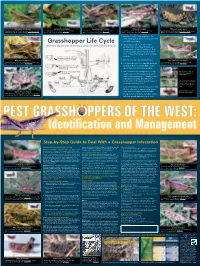

Grasshopper Life Cycle Overwinter As Nymphs

Twostriped grasshopper Redlegged grasshopper Clearwinged grasshopper Striped grasshopper Differential grasshopper Takes bran bait well. Pest of crops, trees, shrubs, and range. Peak hatch Takes bran bait well. Pest of crops and forage. Peak hatch range: Takes bran bait well. Pest of crops and forage. Peak hatch range: Does not take bran bait. Pest of range grasses. Peak hatch range: Takes bran bait well. Pest of crops, trees, and shrubs. Peak hatch range: range: May 15 – June 15. Female body length: June 21 – July 1. Female body length: May 15 – June 15. Female body length: May 15 – June 15. Female body length: June 21 – July 1. Female body length: 1. Hatching usually occurs mid-May to late June. A few species hatch in the summer and Grasshopper Life Cycle overwinter as nymphs. Western grasshoppers produce only one generation per year 2. Grasshoppers have to shed their hard exoskeleton to grow bigger through each nymphal phase (instar) to adulthood. They often hang upside down on grass stems to molt. It takes five to seven days to complete First and second instar nymphs (or an instar. hoppers) are usually less than 3/8” Migratory grasshopper long and no wing pads are visible. 3. Most species have five nymphal instars. Spottedwinged grasshopper Takes bran bait well. Pest of crops, range, and trees. Peak hatch range: Does not take bran bait. Pest of range grasses. Peak hatch range: May 15 – June 15. Female body length: 4. The last molt results in an adult with functional May 15 – June 15. Female body length: Third and fourth instars are usually wings that allow low, evasive flights. -

Grasshoppers

Grasshoppers Orthoptera: Acrididae Plains Lubber Pictured grasshoppers Great crested grasshopper Snakeweed grasshoppers Primary Pest Grasshoppers • Migratory grasshopper • Twostriped grasshopper • Differential grasshopper • Redlegged grasshopper • Clearwinged grasshopper Twostriped Grasshopper, Melanoplus bivittatus Redlegged Grasshopper, Melanoplus femurrubrum Differential Grasshopper, Melanoplus differentialis Migratory Grasshopper, Melanoplus sanguinipes Clearwinged Grasshopper Camnula pellucida Diagram courtesy of Alexandre Latchininsky, University of Wyoming Photograph courtesy of Jean-Francoise Duranton, CIRAD Grasshoppers lay pods of eggs below ground Grasshopper Egg Pods Molting is not for wimps! Grasshopper Nymphs Some grasshoppers found in winter and early spring Velvet-striped grasshopper – a common spring species Grasshopper Controls • Weather (rainfall mediated primarily) • Natural enemies – Predators, diseases • Treatment of breeding areas • Biological controls • Row covers Temperature and rainfall are important mortality factors Grasshoppers and Rainfall Moisture prior to egg hatch generally aids survival – Newly hatched young need succulent foliage Moisture after egg hatch generally reduces problems – Assists spread of diseases – Allows for plenty of food, reducing competition for rangeland and crops Grasshopper predators Robber Flies Larvae of many blister beetles develop on grasshopper egg pods Blister beetle larva Fungus-killed Grasshoppers Pathogen: Entomophthora grylli Mermis nigrescens, a nematode parasite of grasshoppers -

Pehr Kalm's Description of the Periodical Cicada, Magicicada Septendecim L.1

PEHR KALM'S DESCRIPTION OF THE PERIODICAL CICADA, MAGICICADA SEPTENDECIM L.1 From Kongl. Svenska Vetenskaps Academiens Handlingar, 17: 101-116, 1756. Trans- lated by Esther Louise Larsen (Mrs. K. E. Doak) of Crown Point, Ind.., and submitted for publication by Professor J. J. Davis, Purdue University, Lafayette, Ind. INTRODUCTION In 1749, a heavy infestation of the periodical cicada occurred in Pennsylvania. Pehr Kalm, who was visiting there, described in detail the insect in its 18th century surroundings. His paper was published in Kongl. Svenska Vetenskaps Academiens, Handlingar, 17: 101-116, 1756, under the title "Beskrifning pa et slags Grashopper uti Norra America" (Description of a type of Grasshopper in North America). Because of the misleading title, it is doubtful that many scientists are aware of the existence of this early report on the periodical cicada. Kalm refers to the insect as a type of grasshopper, but he also says that it may well prove to be a cicada. The annual cicada, which Kalm and his contemporaries heard, was thought to be a vagrant periodical cicada. Although he was not clear on the taxonomy of the insect, his sharp observa- tions have given us an accurate account of the infestation. Among the many flying insects in North America there is a species of grass- hopper which seems to merit special discussion because of its extraordinary characteristics. The English refer to this species as locust, the Swedes, grashoppor. The Latin name may well be Cicada, maxilla utraque lineis octo transversis concavis; alarum margine inferiore lutescents. This cicada would seem to be exactly the same species as that found in the Provence and Languedoc in France, which is illustrated and described by Mr. -

1 Summer Smorgasbord of Environmental Learning: the Insect

Summer Smorgasbord of Environmental Learning: The Insect Orchestra Warm summer days and nights in New Jersey come with the gentle chirping of the insect orchestra. Summer weather brings out a variety of insects that you have probably heard before. You just have to know what to listen for to detect them by sound, so let’s start listening and learning! Let’s Meet the Musicians Grasshoppers, crickets, and katydids all belong to the same taxonomy order called Orthoptera. Insects in this order share a few common characteristics including modified and long hind legs meant for jumping, chewing mouth parts, and the ability to create a unique song by rubbing specific body parts together. The reason for these insects’ songs is an attempt to attract a mate. Grasshoppe r: The mid-day pick-me-up Cricket: The evening vocalist Katydid: The late-night star Grasshoppers are a daytime insect with short antennae. They eat mainly vegetations including grasses, and leaves, but they will also eat flowers, stems, and seeds. On occasion they will scavenge for dead insects as well. As their name suggests, if you are ever walking through grasslands or a meadow keep your eye out for the hopping creatures as they prefer to be tucked away in tall grasses. You may hear them before you see them. If you hear a noise that sounds like a gentle flickering it might be a grasshopper. They “sing” or make noise by rubbing their long legs against their wings. They can detect sound by their little ears that are located on the base of their abdomen. -

The Humming Sound of Summer!

by Cindy Steele The Humming Sound of Summer! Welcome back to Puddles’ Craft Corner. You just know it’s gonna be a scorcher when you hear the cicadas in the morning. They sound like 90 degrees in August; like sizzling, sticky heat bubbling over and down the tops of the trees around you. They sound like ice cream trucks, lawnmowers, kids playing in the pool, and the clink of ice in a glass of lemonade—cicadas stealthily singing in the backdrop as if they were there all along. A cicada is an insect of the order Hemiptera, suborder Auchenorrhyncha, in the superfamily Cicadoidea, with big eyes wide apart on the head and usually transparent, well-veined wings. There are approximately 2,500 species of cicada around the globe. Cicadas live in warm climates where they are one of the most widely recognized of all insects, mainly due to their large size and remarkable (and often inescapable) acoustic talents. Cicadas are sometimes called "locusts", although they are unrelated to true locusts, which are a kind of grasshopper. Cicadas are actually related to leafhoppers and spittlebugs. Fun Fact - Some researchers have put cicadas at the top of the list of the loudest insects on the planet. Cicadas start their lives as eggs. Females lay 200 to 400 eggs in tiny holes that they make in the branches of trees and shrubs. After six to 10 weeks, cicada young, called nymphs, hatch from the eggs, and immediately fall to the ground. They burrow underground and attach to tree roots. The nymphs stay buried to suck tree sap from two to 17 years, depending on the species. -

Traditional Insect Bioprospecting – As Human Food and Medicine

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 8 (4), October 2009, pp. 485-494 Traditional insect bioprospecting – As human food and medicine SK Srivastava*, Naresh Babu & Hema Pandey National Research Centre for Women in Agriculture, (NRCWA), (Indian Council of Agricultural Research), P.O. Baramunda, Bhubaneswar 751 003, Orissa E-mail: [email protected] Received 29.May 2007; revised 22.September.2008 The wisdom that indigenous people have regarding bioprospecting is embedded in their belief system and their culture. Food insects play an important role in the new insect focus. Ants, bees, termites, caterpillars, water bugs, beetle larvae, flies, crickets, katydids, cicadas, and dragonfly nymphs are among a long list of edible insects that provide nutrition for the people of Asia, Australia, Africa, South America, the Middle East, and the Far East. Insects represent an important food source for a wide variety of other animal species. By weight, termites, grasshoppers, caterpillars, weevils, houseflies and spiders are better sources of protein than beef, chicken, pork or lamb. The traditional healers use Insects as medicine. Chemicals produced by insects against self defense can be used for antibacterial and anticancer drugs. The nutritional and economic value of edible insects is often neglected and we should further encourage their collection and commercialization, given the benefits to the environment and human health. It is an interesting concept, managing pest insects by developing them into a sought after delicacy. Keywords: Insectivory, Entomophagy, Traditional knowledge, Insect bioprospecting IPC Int. Cl. 8: A61K36/00, A61K35/64, A61P19/02, A61P15/08, A61P27/12, A61P11/06, A61P25/20 Bioprospecting is the collecting and cribbling of Insects as food biological samples (plants, animals, microorganisms) Insects represent an important food source for a and the collecting of indigenous knowledge to help in wide variety of other animal species. -

Dichotomous Key to Orders

FRST 307 Introduction to Entomology KEY TO COMMON INSECT ORDERS What is a Key? In biological sciences a “key” is a written tool used to determine the taxonomic identification of plants, animals, soils, etc. For this lab, a key will be used to identify insects to Order. More detailed identifications to family, genus and species are beyond the scope of this course, but can be accomplished using appropriate guides available from the library. Taking a Closer Look Because insects are so small, differentiating among species, families and even orders is often difficult. However, examination beneath a hand lens or microscope will allow you to see many of the characters mentioned in the key. Why Use a Key? Sometimes, you can identify an insect quickly by comparing it to pictures in field guides or on the internet. Pictures are a great tool, but the use of a key is essential to guarantee that your identification is accurate. Why? Because some insects, even ones from separate orders, can look almost exactly alike. For example, many flies (order Diptera) look almost exactly like wasps (order Hymenoptera). Using your key, you will find that a fly has 1 pair of wings, whereas wasps have 2 pairs of wings. Key to Adult Insects Only Remember - immature insects and adult insects are often very different. This is especially true for holometabolous (complete metamorphosis) insects where the immature stages are larvae and pupae. The key included in this guide is only useful for keying adult insects to order. Also, this key does not cover other creatures related to insects, like spiders, sowbugs, and centipedes. -

<I>Melanoplus Sanguinipes</I> (Fab.)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Distance Master of Science in Entomology Projects Entomology, Department of 2016 The iologB y, Ecology, and Management of the Migratory Grasshopper, Melanoplus sanguinipes (Fab.) Dewey W. Murray USDA-APHIS and University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entodistmasters Part of the Entomology Commons Murray, Dewey W., "The ioB logy, Ecology, and Management of the Migratory Grasshopper, Melanoplus sanguinipes (Fab.)" (2016). Distance Master of Science in Entomology Projects. 13. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entodistmasters/13 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Distance Master of Science in Entomology Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Biology, Ecology and Management of the Migratory grasshopper, Melanoplus sanguinipes (Fab.). Dewey W. Murray1 USDA-APHIS, Phoenix, Arizona 85040; email: [email protected] Keywords Rangeland, suppression treatments, economic species, flight, outbreaks, economic threshold, population dynamics. Abstract Grasshoppers have caused significant damage to crops of farmers and rangeland forage of ranchers throughout history. Populations of grasshoppers can build and explode with exponential growth under the right climatic factors and habitat. Melanoplus sanguinipes is the most economic species of grasshopper in the United States. The migratory flight capabilities is very similar to true locusts. This species as been known to travel distances of over 500 miles. Millions of dollars in damage occurs to crops and rangeland annually in the United States due to this species and other economic grasshopper species. -

The Periodical Cicada

BULLETIN NO. 14, NEW SERIES. U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. DIVISION OF ENTOMOLOGY. THE PERIODICAL CICADA. AN ACCOUNT OF CICADA SEPTENDECIM, ITS NATURAL ENEMIES AND THE MEANS OF PREVENTING ITS INJURY, TOGETHER WITH A SUMMARY OF THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE DIFFERENT BROODS. C. JJ. MAELATT, M. S., FIRST ASSISTANT ENTOMOLOGIST. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1898. 1, So, 14, new series, Div. of Entomology, U. S. Dept. of Agriculture. frontispiece. !'hilo I V Riley.del L.SuIhv m p TRANSFORMATION OF CICADA SEPTENDECIM —*"— " R E C £ ' V E D "n.ftv vVoA\ .v ;P-M o 'HÖH w >* ■ • • ^ ; _; __ ÛTsT Departmen^o^Agriculture^ BULLETIN No. 14, NEW SERIES. U. S. DEPARTMEiNT OF AGRICULTURE. DIVISION OF ENTOMOLOGY. THE PERIODICAL CICADA. AN ACCOUNT OF CICADA SEPTENDECIM, ITS NATURAL ENEMIES AND THE MEANS OF PREVENTING ITS INJURY, TOGETHER WITH A SUMMARY OF TUB DISTRIBUTION OF THE DIFFERENT BROODS. C. L. M AUL, ATT, M. S. FIIIST ASSISTANT ENTOMOLOGIST WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1898. DI VISTON OF ENTOMOLOG Y. Entomologist : L. O. Howard. Assist. Entomologists : C. L. Marlatt, Th. Pergande, Frank Benton. Investigators : E. A. Schwarz, H. G. Hubbard, D. W. Coquillett, F. H. Chittenden. Assistants : R. S. Clifton, Nathan Banks, F. C. Pratt, August Busck. Artist: Miss L. Sullivan. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL IL S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, DIVISION OF ENTOMOLOGY, Washington, D. (7., May 1, 1898. SIR : The periodical, or seventeen-year, Cicada has a peculiar interest in addition to its economic importance, in that it is distinctly American and has the longest life period of any known insect. Economically, it is chiefly important in the adult stage from the likelihood of its injuring nursery stock and young fruit trees by depositing its eggs.