Consumers' Acceptability and Creative Use of Local Fabrics As Graduation Gown for Primary School Pupils Amubode Adetoun Adedot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamic Art from the Collection, Oct. 23, 2020 - Dec

It Comes in Many Forms: Islamic Art from the Collection, Oct. 23, 2020 - Dec. 18, 2021 This exhibition presents textiles, decorative arts, and works on paper that show the breadth of Islamic artistic production and the diversity of Muslim cultures. Throughout the world for nearly 1,400 years, Islam’s creative expressions have taken many forms—as artworks, functional objects and tools, decoration, fashion, and critique. From a medieval Persian ewer to contemporary clothing, these objects explore migration, diasporas, and exchange. What makes an object Islamic? Does the artist need to be a practicing Muslim? Is being Muslim a religious expression or a cultural one? Do makers need to be from a predominantly Muslim country? Does the subject matter need to include traditionally Islamic motifs? These objects, a majority of which have never been exhibited before, suggest the difficulty of defining arts from a transnational religious viewpoint. These exhibition labels add honorifics whenever important figures in Islam are mentioned. SWT is an acronym for subhanahu wa-ta'ala (glorious and exalted is he), a respectful phrase used after every mention of Allah (God). SAW is an acronym for salallahu alayhi wa-sallam (may the blessings and the peace of Allah be upon him), used for the Prophet Muhammad, the founder and last messenger of Islam. AS is an acronym for alayhi as-sallam (peace be upon him), and is used for all other prophets before him. Tayana Fincher Nancy Elizabeth Prophet Fellow Costume and Textiles Department RISD Museum CHECKLIST OF THE EXHIBITION Spanish Tile, 1500s Earthenware with glaze 13.5 x 14 x 2.5 cm (5 5/16 x 5 1/2 x 1 inches) Gift of Eleanor Fayerweather 57.268 Heavily chipped on its surface, this tile was made in what is now Spain after the fall of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada (1238–1492). -

Headwear How Do YOU Get Ahead? the TRICK to GETTING Ahead in TODAY’S VAST SEA of RETAIL IS to CAST a WIDE NET in ORDER to GATHER up ALL CUSTOMERS WHO ENTER YOUR SHOP

Headwear How do YOU get Ahead? THE TRICK TO GETTING Ahead IN TODAY’S VAST SEA OF RETAIL IS TO CAST A WIDE NET IN ORDER TO GATHER UP ALL CUSTOMERS WHO ENTER YOUR SHOP. OUR ALTERNATIVE GRAPHICS AND KNACK FOR PAIRING UP THE RIGHT ORNAMENTATION TECHNIQUE FOR EACH PIECE, SATISFIES CUSTOMERS OF ALL AGES AND TASTES. BAIT YOUR SHOPPERS WITH Ahead’s GREAT STYLING, MODERN FABRICS, AND ON TREND COLORS TO KEEP THOSE DOLLARS FROM SWIMMING AWAY. Ahead HAS BEEN SUCCESSFULLY FISHING IN THESE WATERS FOR OVER 20 YEARS... join us! Felt Appliqué Chain Stitch Direct Embroidery Printed Rubber Appliqué Bounce Stitch Printed Vintage Label Twill Patch Vintage Label w/Embroidery What drives Us to be Ahead? New Bedford Heritage: It’s in the Water & Soil! Farmers will tell you that the best tasting crops owe it to the water and soil. They discount, or perhaps don’t even realize, the know-how and work ethic that they inherited from those before them. The crew at Ahead is very similar. Hard work comes naturally to our staff as a result of the industries that their New Bedford ancestors pioneered. Today, the city’s thriving arts community helps to drive creativity within Ahead’s walls. In the 1800s, whale oil was After whaling, Textile mills After The Great Depression, used for lamps, candles, & boomed, & skilled workers 2/3s of New Bedford’s mills household items. The tireless from around the world mi- closed. Decades later, artists sailors of New Bedford’s grated to the area. By 1905, began gravitating to the whaling ships landed enough about 80% of the residents impoverished city in search Leviathans to make the city had arrived from Portugal, of inexpensive lofts. -

Mud Cloth from Mali: Its Making and Use

ISSN 0378-5254 Tydskrif vir Gesinsekologie en Verbruikerswetenskappe, Vol 31, 2003 Mud cloth from Mali: its making and use Elsje S Toerien OPSOMMING INTRODUCTION Bogolanfini van Mali, beter bekend as mud cloth, The stark, geometric, black and white designs tradi- het in die laaste aantal jare bekendheid verwerf en tionally found on the mud cloths from Mali, can today daarby ook baie gewild geraak. be found on everything from clothing and furniture to book covers and wrapping paper. Along with kente Vir baie jare was dit nie duidelik hoe hierdie kleed- (from Ghana), mud cloth has become one of the best- stof gemaak is nie. Dit was algemeen aanvaar dat known African cloth traditions worldwide (Clarke, die ontwerpe deur 'n bleikingsproses verkry is. Van- 2001). Luke-Boone (2001:8) describes it as 'probably dag is dit bekend dat die ligte ontwerpe verkry word the most influential ethnic fabric of the 1990's'. The deur hulle met donker modder te omlyn en daarna designs have indeed become an important part of the die agtergrond in te vul. Afgesien van bogolanfini se modern ethnic look found in African-inspired fashions dekoratiewe waarde, het die verskillende motiewe today. ook simboliese waarde, en word verskillende kom- binasies gebruik om 'n geskiedkundige gebeurtenis te herdenk of 'n plaaslike held te vereer. In hierdie artikel word daar gekyk na die tegnieke wat gebruik word om bogolanfini te maak, na die betekenis van sommige motiewe, en die verskillen- de maniere waarop die tegnieke of motiewe gebruik word. Die redes vir die verhoogde belangstelling in, en vervaardiging van bogolanfini word ook aange- spreek. -

3D Weaving Process : Development of Near Net Shape Preforms and Verification of Mechanical Properties

Vol. 34, No. 2, 96-100 (2021) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7234/composres.2021.34.2.096 ISSN 2288-2103(Print), ISSN 2288-2111(Online) Paper 3D Weaving Process : Development of Near Net Shape Preforms and Verification of Mechanical Properties Vinzenz Klapper*,**,***, Kwang-Hoon Jo*, Joon-Hyung Byun*, Jung-Il Song**, Chee-Ryong Joe**† ABSTRACT: The lightweight industry continuously demands reliable near-net-shape fabrication where the preform just out-of-machine is close to the final shape. In this study, different half-finished preforms are made π-beams. Then the preforms are unfolded to make a 3D shape with integrated structure of fibers, providing easier handling in the further processing of composites. Several 3D textile preforms are made using weaving technique and are examined after resin infusion for mechanical properties such as inter-laminar shear strength, compressive strength and tensile strength. Considering that the time and labor are important parameters in modern production, 3D weaving technique reduces the manufacturing steps and therefore the costs, such as hand-lay up of textile layers, cutting, and converting into preform shape. Hence this 3D weaving technique offers many possibilities for new applications with efficient composite production. Key Words: 3D weaving, weave pattern, π-beam, T-joint 1. INTRODUCTION connection in position and length by the warp yarn is offering many possibilities to create 3D textile preforms. With 3D To reduce the product weight and material cost, the light- weaving techniques, many integrated structural solutions such weight industry is continuously demanding a preform that is as different beam types and stiffeners can be produced [4]. -

An Empirical Assessment of the Relationship Of

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 7 (2), Serial No. 29, April, 2013:350-370 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.7i2.22 Adire in South-western Nigeria: Geography of the Centres Areo, Margaret Olugbemisola- Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] & Kalilu, Razaq Olatunde Rom - Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] Abstract Adire, the patterned dyed cloth is extant and is practiced in almost all Yoruba towns in Southwestern Nigeria. The art tradition is however preponderant in a few Yoruba towns to the extent that the names of these towns are traditionally inseparable with the Adire art tradition. With Western education, introduction of foreign religions, influence from other cultures, technique and technology, there is a shift in the producers of Adire, the training pattern, and even an evolution in the production centre. While Western education resulted in a shift from the hitherto traditional Copyright© IAARR 2013: www.afrrevjo.net 350 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. 7 (2) Serial No. 29, April, 2013 Pp.350-370 apprenticeship method to the study of the art in schools, unemployment gave birth to the introduction of training drives by government and non governmental parastatals. This study, a field research, is an appraisal of the factors that contributed to the vibrancy of the traditionally renowned centres, and how the newly evolved centres have in contemporary times contributed to the sustainability of the Adire art tradition. -

USA Net Price List (Prices Not Applicable for Markets Outside USA) Carnegiefabrics.Com 800.727.6770

USA Net Price List (Prices not applicable for markets outside USA) carnegiefabrics.com 800.727.6770 USA Net Price List Effective January 6, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................ 3 FABRIC FINISHES ............................................................................................. 8 PRICE LIST, ALPHABETICAL ........................................................................... 13 A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | Z PRICE LIST, NUMERICAL ................................................................................ 46 2000 | 4000 | 5000 | 6000 | 7000 | 8000 | 30000 | 100000 Net Pricelist January 2021 2 carnegiefabrics.com 800.727.6770 General Information PRICES Prices shown are the net wholesale costs per linear yard F.O.B Rockville Centre, N.Y. Prices are not applicable for markets outside USA. Please see carnegiefabrics.com for listings of our International Distribution Partners. These prices are subject to change without notice. We therefore suggest that before concluding a transaction you confirm prices with our Rockville Centre office or your local sales representative. SALES SERVICES To place orders, request samples or for other general information, please contact Carnegie Sales Services, Monday through Thursday, 8:30am - 5:30pm. Friday, 8:30am - 5:00pm, Eastern time. Carnegie 110 North Centre Avenue Rockville Centre, New York 11570 Tel. (800)727-6770 Tel. (516)678-6770 Fax (516)307-3765 [email protected] TERMS OF SALE Terms are net 30 days for customers with open accounts. You may apply for an open account by sending us the names, addresses, and fax numbers of four trade credit references and your bank with your account number. INSPECTION All orders are carefully inspected before shipment for pattern, color, quality and yardage. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

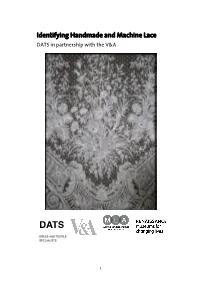

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

The “African Print” Hoax: Machine Produced Textiles Jeopardize African Print Authenticity

The “African Print” Hoax: Machine Produced Textiles Jeopardize African Print Authenticity by Tunde M. Akinwumi Department of Home Science University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria Abstract The paper investigated the nature of machine-produced fabric commercially termed African prints by focusing on a select sample of these prints. It established that the general design characteristics of this print are an amalgam of mainly Javanese, Indian, Chinese, Arab and European artistic tradition. In view of this, it proposed that the prints should reflect certain aspects of Africanness (Africanity) in their design characteristics. It also explores the desirability and choice of certain design characteristics discovered in a wide range of African textile traditions from Africa south of the Sahara and their application with possible design concepts which could be generated from Macquet’s (1992) analysis of Africanity. This thus provides a model and suggestion for new African prints which might be found acceptable for use in Africa and use as a veritable export product from Africa in the future. In the commercial parlance, African print is a general term employed by the European textile firms in Africa to identify fabrics which are machine-printed using wax resins and dyes in order to achieve batik effect on both sides of the cloth, and a term for those imitating or achieving a resemblance of the wax type effects. They bear names such as abada, Ankara, Real English Wax, Veritable Java Print, Guaranteed Dutch Java Hollandis, Uniwax, ukpo and chitenge. Using the term ‘African Print’ for all the brand names mentioned above is only acceptable to its producers and marketers, but to a critical mind, the term is a misnomer and therefore suspicious because its origin and most of its design characteristics are not African. -

African Lace

Introduction Does changing an original material destroy its traditional context? If a material assumes new meaning or significance in a new context, is this inherently an appropriation of the object? What loss does this cause, and is it a positive change, a negative one, or neither? This lexicon revolves around African Lace. Through an analysis of this particular material, I broadly explain, craftsmanship, authenticity and reasons behind an object’s creation, including why and how it is made, from which materials, and how the object translates into a specific environment. Various kinds of objects are created in and relate to specific places and time periods. If situated in an environment in which it did not originate, the meaning of an object changes. In fact, the object is used from a new perspective. Although it is possible to reuse an object as a source of inspiration or research, it cannot be used as it was in its previous context. Thus, it is necessary to rethink the authenticity of an object when it is removed from its past context. History is important and can explain a materials origin, and it therefore warrants further attention. A lack of knowledge results in a loss of authenticity and originality of a historical material. In view of this, I develop this Lexicon to elaborate on the importance of this historical attention. It is interesting to consider how an object can influence a user in relation to emotional or even material value. The extent of this influence is uncertain, but it is a crucial aspect since any situation could diminish the value and the meaning of an object. -

Indigo and the Tightening Thread 1 for the Journal of Weavers, Spinners and Dyers 231 Autumn 2009

Indigo and the Tightening Thread 1 For the Journal of Weavers, Spinners and Dyers 231 Autumn 2009 Jane Callender Natural indigo and synthetic Many varieties of indigo bearing plants flourish in indigo are both available to us. hot and temperate climates all over the world A key date in textile history is and more than one can be found in any one 1856 when 18 year old assistant region. The European indigo bearing plant is chemist William Perkins, Isastis Tinctoria, known as woad. stumbled upon, developed and Although there are an incredible number of patented the first synthetic species and subspecies, ‘indican’, the actual dyestuff from coal tar. ‘Perkins chemical source and precursor of indigo, a tiny Purple’ became known as organic molecule, is common to all. (A Large Mauvine. Later the German percentage in the woad precursor is also indican, chemist Adolf von Baeyer with Isatan B making up the rest) Consequently synthesized indigo which was ‘…..the resulting blue is indistinguishable even to sold on the open market in the specialist’ (Balfour-Paul) 1897. Astonishingly, the Harvesting the plants, extracting the indican molecular structure of natural present within the leaves and storage of the and synthetic indigo, as it was indigo pigment differs from country to country. then and as it is now, is the Though glycosides and enzymes vary, as does the same. alkalinity level and temperature of the water in which leaves are immersed, the following Dyeing can only be done graphics illustrates, in essence, the acquisition of with indigo in its soluble form natural indigo through fermentation. -

Utilization of Nigerian Made Fabrics for Garment Making Among Academic and Non Academic Female Staff in Enugu State

UTILIZATION OF NIGERIAN MADE FABRICS FOR GARMENT MAKING AMONG ACADEMIC AND NON ACADEMIC FEMALE STAFF IN ENUGU STATE BY AGBO BLESSING NONYELUM PG/M.Ed/12/64238 DEPARTMENT OF HOME ECONOMICS AND HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA JUNE, 2017. TITLE PAGE UTILIZATION OF NIGERIAN MADE FABRICS FOR GARMENT MAKING AMONG ACADEMIC AND NON ACADEMIC FEMALE STAFF IN ENUGU STATE BY AGBO BLESSING NONYELUM PG/M.Ed/12/64238 A RESEARCH REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HOME ECONOMICS AND HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA NSUKKA, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTERS DEGREE IN CLOTHING AND TEXTILE JUNE, 2017 APPROVAL PAGE The project has been approved for the Department of Home Economics and Hospitality Management Education, University of Nigeria, Nsukka DR. MRS. N. M. EZE Prof. E. U. ANYAKOHA Supervisor Head of Department ________________________ ____________________________ External Examiner Internal Examiner _____________________________________ Prof. C.A. Igbo Dean, Faculty of Vocation and Technical Education CERTIFICATION AGBO, BLESSING NONYELUM, a Postgraduate student in the Department of Home Economics and Hospitality Management Education with Registration Number PG/M.ED/12/64238, has satisfactorily completed the requirements for the award of Masters Degree in Home Economics Education (Clothing and Textile). The work embodied in this project is original and has not been submitted in part or full for another diploma or degree in this or any other university. _________________________ ____________________________ AGBO, BLESSING N. DR. N.M. EZE Student Supervisor DEDICATION This research work is dedicated to Almighty God for granting me wisdom, guidance and protection throughout the period of this study. -

“We Are Nigeria”

“WE ARE NIGERIA” CHAPTER ONE ‘Who can tell me what happened on the 1st of October 1960?’ asked our class teacher. None of the students wanted to answer the question. Our teacher looked around the class and we hid our faces because we knew what she was going to do next. ‘Jay’ She said, and he almost jumped out of his chair. ‘Please answer the question.’ She always picked a student randomly to answer questions when no one volunteered. ‘It was the day Nigeria defeated the Queen of England’ Jay got up to answer the question. His voice was a shaky whisper. Jay was always nervous when he had to answer questions in class. ‘Yes Didi’ our teacher said and the class turned to look at me as I stood up to answer the question. ‘Class, did you hear him?’ our teacher asked. ‘No ma’ the class chorused. Their mocking voices ‘Before the 1st of October 1960, Nigeria was ruled by made Jay more nervous. Great Britain. The Queen of England, Queen Elizabeth the second was the Head of Government of ‘It was the day Nigeria defeated the Queen of Nigeria. Before independence, the money we spent England’ Jay repeated louder and the class erupted in Nigeria was pounds and shillings; the British people in laughter. taught us their language and that is why English language is the primary language in Nigeria.’ ‘Students, please be quiet’ she scolded and the class went quiet. I was enjoying all the attention as the class listened to me attentively. ‘Good effort Jay’ she said but we knew she was only trying to encourage him.