The Assassination of Philip II of Macedon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

2019-3337-AJHIS-HIS 1 Alexander the Great and Hephaestion: 2 Censorship and Bisexual Erasure in Post-Macedonian 3 Society 4 5 6 Same-sex relations were common in ancient Greece and having both male and female 7 physical relationships was a cultural norm. However, Alexander the Great is almost 8 always portrayed in modern depictions as heterosexual, and the disappearance of his 9 life-partner Hephaestion is all but complete in ancient literature. Five full primary 10 source biographies of Alexander have survived from antiquity, making it possible to 11 observe the way scholars, popular writers and filmmakers from the Victorian era 12 forward have interpreted this evidence. This research borrows an approach from 13 gender studies, using the phenomenon of bisexual erasure to contribute a new 14 understanding for missing information regarding the relationship between Alexander 15 and his life-partner Hephaestion. In Greek and Macedonian society, pederasty was the 16 norm, and boys and men did not have relations with others of the same age because 17 there was almost always a financial and power difference. Hephaestion was taller and 18 more handsome than Alexander, so it might have appeared that he held the power in 19 their relationship. The hypothesis put forward here suggests that writers have erased 20 the sexual partnership between Alexander and Hephaestion because their relationship 21 did not fit the norm of acceptable pederasty as practiced in Greek and Macedonian 22 culture or was no longer socially acceptable in the Roman contexts of the ancient 23 historians. Ancient biographers may have conducted censorship to conceal any 24 implication of femininity or submissiveness in this relationship. -

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; Proquest Pg

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; ProQuest pg. 159 Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion R. D. Milns SOME TIME between the battle of Gaugamela and the battle of A the Hydaspes the number of battalions in the Macedonian phalanx was raised from six to seven.1 This much is clear; what is not certain is when the new formation came into being. Berve2 believes that the introduction took place at Susa in 331 B.C. He bases his belief on two facts: (a) the arrival of 6,000 Macedonian infantry and 500 Macedonian cavalry under Amyntas, son of Andromenes, when the King was either near or at Susa;3 (b) the appearance of Philotas (not the son of Parmenion) as a battalion leader shortly afterwards at the Persian Gates.4 Tarn, in his discussion of the phalanx,5 believes that the seventh battalion was not created until 328/7, when Alexander was at Bactra, the new battalion being that of Cleitus "the White".6 Berve is re jected on the grounds: (a) that Arrian (3.16.11) says that Amyntas' reinforcements were "inserted into the existing (six) battalions KC1:TCt. e8vr(; (b) that Philotas has in fact taken over the command of Perdiccas' battalion, Perdiccas having been "promoted to the Staff ... doubtless after the battle" (i.e. Gaugamela).7 The seventh battalion was formed, he believes, from reinforcements from Macedonia who reached Alexander at Nautaca.8 Now all of Tarn's arguments are open to objection; and I shall treat them in the order they are presented above. -

Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignity Kristin M.S

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Bookshelf 2015 Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignity Kristin M.S. Bezio University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/bookshelf Part of the Leadership Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bezio, Kristin M.S. Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignty. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2015. NOTE: This PDF preview of Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignity includes only the preface and/or introduction. To purchase the full text, please click here. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bookshelf by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignty KRISTIN M.S. BEZIO University ofRichmond, USA LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND VIRGINIA 23173 ASHGATE Introduction Of Parliaments and Kings: The Origins of Monarchy and the Sovereign-Subject Compact in the English Middle Ages (to 1400) The purpose of this study is to examine the intersection between early modem political thought, the history that produced the late Tudor and early Stuart monarchies, and the critical interrogation of both taking place on the public theatrical stage. The plays I examine here are those which rely on chronicle histories for their source materials; are set in England, Scotland, or Wales; focus primarily on governance and sovereignty; and whose interest in history is didactic and actively political. -

Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Paul K. Kerr Analyst in Nonproliferation Mary Beth Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation August 1, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34248 Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Summary Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal probably consists of approximately 110-130 nuclear warheads, although it could have more. Islamabad is producing fissile material, adding to related production facilities, and deploying additional nuclear weapons and new types of delivery vehicles. Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is widely regarded as designed to dissuade India from taking military action against Pakistan, but Islamabad’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal, development of new types of nuclear weapons, and adoption of a doctrine called “full spectrum deterrence” have led some observers to express concern about an increased risk of nuclear conflict between Pakistan and India, which also continues to expand its nuclear arsenal. Pakistan has in recent years taken a number of steps to increase international confidence in the security of its nuclear arsenal. Moreover, Pakistani and U.S. officials argue that, since the 2004 revelations about a procurement network run by former Pakistani nuclear official A.Q. Khan, Islamabad has taken a number of steps to improve its nuclear security and to prevent further proliferation of nuclear-related technologies and materials. A number of important initiatives, such as strengthened export control laws, improved personnel security, and international nuclear security cooperation programs, have improved Pakistan’s nuclear security. However, instability in Pakistan has called the extent and durability of these reforms into question. Some observers fear radical takeover of the Pakistani government or diversion of material or technology by personnel within Pakistan’s nuclear complex. -

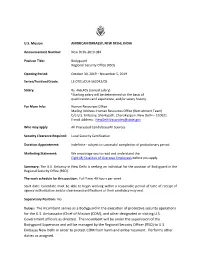

Duties: the Incumbent Serves As a Bodyguard in the Execution of Protective Security Operations for the U.S

U.S. Mission AMERICAN EMBASSY, NEW DELHI, INDIA Announcement Number: New Delhi-2019-084 Position Title: Bodyguard Regional Security Office (RSO) Opening Period: October 30, 2019 – November 5, 2019 Series/Position/Grade: LE-0701 /DLA-562042/05 Salary: Rs. 466,405 (annual salary) *Starting salary will be determined on the basis of qualifications and experience, and/or salary history. For More Info: Human Resources Office Mailing Address: Human Resources Office (Recruitment Team) C/o U.S. Embassy, Shantipath, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi – 110021. E-mail Address: [email protected] Who may apply: All Interested Candidates/All Sources Security Clearance Required: Local Security Certification Duration Appointment: Indefinite - subject to successful completion of probationary period Marketing Statement: We encourage you to read and understand the Eight (8) Qualities of Overseas Employees before you apply. Summary: The U.S. Embassy in New Delhi is seeking an individual for the position of Bodyguard in the Regional Security Office (RSO). The work schedule for this position: Full Time; 40 hours per week Start date: Candidate must be able to begin working within a reasonable period of time of receipt of agency authorization and/or clearances/certifications or their candidacy may end. Supervisory Position: No Duties: The incumbent serves as a Bodyguard in the execution of protective security operations for the U.S. Ambassador/Chief of Mission (COM), and other designated or visiting U.S. Government officials as directed. The incumbent will be under the supervision of the Bodyguard Supervisor and will be managed by the Regional Security Officer (RSO) to U.S. Embassy New Delhi in order to protect COM from harm and embarrassment. -

The Oath a Film by Laura Poitras

The Oath A film by Laura Poitras POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDe The Oath POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers New YorK , 2010 I was first interested in making a film about Guantanamo in 2003, when I was also beginning a film about the war in Iraq. I never imagined Guantanamo would still be open when I finished that film, but sadly it was — and still is today. originally, my idea for the Oath was to make a film about some - one released from Guantanamo and returning home. In May 2007, I traveled to Yemen looking to find that story and that’s when I met Abu Jandal, osama bin Laden’s former bodyguard, driving a taxicab in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. I wasn’t look - ing to make a film about Al-Qaeda, but that changed when I met Abu Jandal. Themes of betrayal, guilt, loyalty, family and absence are not typically things that come to mind when we imagine a film about Al-Qaeda and Guantanamo. Despite the dangers of telling this story, it compelled me. Born in Saudi Arabia of Yemeni parents, Abu Jandal left home in 1993 to fight jihad in Bosnia. In 1996 he recruited Salim Ham - dan to join him for jihad in Tajikistan. while traveling through Laura Poitras, filmmaker of the Oath . Afghanistan, they were recruited by osama bin Laden. Abu Jan - Photo by Khalid Al Mahdi dal became bin Laden's personal bodyguard and “emir of Hos - pitality.” Salim Hamdan became bin Laden’s driver. Abu Jandal ends up driving a taxi and Hamdan ends up at Guantanamo. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

The Court of Alexander the Great As Social System

Originalveröffentlichung in Waldemar Heckel/Lawrence Tritle (Hg.), Alexander the Great. A New History, Malden, Mass. u.a. 2009, S. 83-98 5 The Court of Alexander the Great as Social System Gregor Weber In his discussion of events that followed Alexander ’s march through Hyrcania (summer 330), Plutarch gives a succinct summary of the king ’s conduct and reports the clash of his closest friends, Hephaestion and Craterus (Alex. 47.5.9-11).1 The passage belongs in the context of Alexander ’s adoption of the traditions and trap pings of the dead Persian Great King (Fredricksmeyer 2000; Brosius 2003a), although the conflict between the two generals dates to the time of the Indian campaign (probably 326). It reveals not only that Alexander was subtly in tune with the atti tudes of his closest friends, but also that his changes elicited varied responses from the members of his circle. Their relationships with each other were based on rivalry, something Alexander - as Plutarch ’s wording suggests - actively encouraged. But it is also reported that Alexander made an effort to bring about a lasting reconcili ation of the two friends, who had attacked each other with swords, and drawn their respective troops into the fray. To do so, he had to marshal “all his resources ” (Hamilton 1969; 128-31) from gestures of affection to death threats. These circumstances invite the question: what was the structural relevance of such an episode beyond the mutual antagonism of Hephaestion and Craterus? For these were not minor protagonists, but rather men of the upper echelon of the new Macedonian-Persian empire, with whose help Alexander had advanced his con quest ever further and exercised his power (Berve nos. -

Mercenaries, Poleis, and Empires in the Fourth Century Bce

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts ALL THE KING’S GREEKS: MERCENARIES, POLEIS, AND EMPIRES IN THE FOURTH CENTURY BCE A Dissertation in History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies by Jeffrey Rop © 2013 Jeffrey Rop Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 ii The dissertation of Jeffrey Rop was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark Munn Professor of Ancient Greek History and Greek Archaeology, Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Gary N. Knoppers Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, Religious Studies, and Jewish Studies Garrett G. Fagan Professor of Ancient History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Kenneth Hirth Professor of Anthropology Carol Reardon George Winfree Professor of American History David Atwill Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Graduate Program Director for the Department of History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Greek mercenary service in the Near East from 401- 330 BCE. Traditionally, the employment of Greek soldiers by the Persian Achaemenid Empire and the Kingdom of Egypt during this period has been understood to indicate the military weakness of these polities and the superiority of Greek hoplites over their Near Eastern counterparts. I demonstrate that the purported superiority of Greek heavy infantry has been exaggerated by Greco-Roman authors. Furthermore, close examination of Greek mercenary service reveals that the recruitment of Greek soldiers was not the purpose of Achaemenid foreign policy in Greece and the Aegean, but was instead an indication of the political subordination of prominent Greek citizens and poleis, conducted through the social institution of xenia, to Persian satraps and kings. -

CAN WORDS PRODUCE ORDER? Regicide in the Confucian Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lirias CAN WORDS PRODUCE ORDER? Regicide in the Confucian Tradition CARINE DEFOORT KU Leuven, Belgium ᭛ ABSTRACT This article presents and evaluates a dominant traditional Chinese trust in language as an efficient tool to promote social and political order. It focuses on the term shi (regicide or parricide) in the Annals (Chunqiu). This is not only the oldest text (from 722–481 BCE) regularly using this term, but its choice of words has also been considered the oldest and most exemplary instance of the normative power of language. A close study of its uses of ‘regi- cide’ leads to a position between the traditional ‘praise and blame’ theory and its extreme negation. Later commentaries on the Annals and reflection on regicide in other texts, in different ways, attest to a growing reliance or belief in the power of words in the political realm. Key Words ᭛ Annals (Chunqiu) ᭛ China ᭛ language ᭛ order ᭛ regicide Two prominent scholars hold a debate in front of Emperor Jing (156–41 BCE). One of them is Master Huang, a follower of Huang Lao and the teachings of ‘The Yellow Emperor and Laozi’. The other is Master Yuan Gu, a specialist in the Book of Odes and appointed as erudite at the court of Emperor Jing. Master Huang launches the discussion with the provoca- tive claim that Tang and Wu, the founding fathers of China’s two exem- plary dynasties, respectively the Shang (18th–11th century) and Zhou (11th–3rd century) dynasties, were guilty of regicide against Jie and Zhòu, the last kings of the preceding dynasties. -

A HISTORY of the PELASGIAN THEORY. FEW Peoples Of

A HISTORY OF THE PELASGIAN THEORY. FEW peoples of the ancient world have given rise to so much controversy as the Pelasgians; and of few, after some centuries of discussion, is so little clearly established. Like the Phoenicians, the Celts, and of recent years the Teutons, they have been a peg upon which to hang all sorts of speculation ; and whenever an inconvenient circumstance has deranged the symmetry of a theory, it has been safe to ' call it Pelasgian and pass on.' One main reason for this ill-repute, into which the Pelasgian name has fallen, has been the very uncritical fashion in which the ancient statements about the Pelasgians have commonly been mishandled. It has been the custom to treat passages from Homer, from Herodotus, from Ephorus, and from Pausanias, as if they were so many interchangeable bricks to build up the speculative edifice; as if it needed no proof that genealogies found sum- marized in Pausanias or Apollodorus ' were taken by them from poems of the same class with the Theogony, or from ancient treatises, or from prevalent opinions ;' as if, further, ' if we find them mentioning the Pelasgian nation, they do at all events belong to an age when that name and people had nothing of the mystery which they bore to the eyes of the later Greeks, for instance of Strabo;' and as though (in the same passage) a statement of Stephanus of Byzantium about Pelasgians in Italy ' were evidence to the same effect, perfectly unexceptionable and as strictly historical as the case will admit of 1 No one doubts, of course, either that popular tradition may transmit, or that late writers may transcribe, statements which come from very early, and even from contemporary sources.