A Framework to Approach Shared Use of Mining-Related Infrastructure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Army Container Operations

FM 55-80 ARMY CONTAINER OPERATIONS DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY FM 55-80 FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS No. 55-80 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 13 August 1997 ARMY CONTAINER OPERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE.......................................................................................................................... iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO INTERMODALISM .......................................... 1-1 1-1. Background.................................................................................... 1-1 1-2. Responsibilities Within the Defense Transportation System............. 1-1 1-3. Department of Defense ................................................................... 1-2 1-4. Assistant Deputy Under Secretary of Defense, Transportation Policy............................................................................................. 1-2 1-5. Secretary of the Army..................................................................... 1-2 1-6. Supported Commander in Chiefs..................................................... 1-2 1-7. Army Service Component Commander............................................ 1-2 1-8. Commanders .................................................................................. 1-2 1-9. United States Transportation Command .......................................... 1-3 1-10. Military Traffic Management Command ......................................... 1-3 1-11. Procurement and Leasing -

Railcars at Rocky Flats Community Final 11-04-04.Indd

Rocky Flats Fact Sheet Transporting low-level radioactive waste from Rocky Flats using railcars Transporting low-level radioactive waste from Rocky Flats using railcars The Rocky Flats Closure Project is one of the largest environmental cleanup operations in the world. Rocky Flats, located approximately 15 miles northwest of Denver, produced plutonium and uranium components for the U.S. nuclear weapons program from 1953 until 1989. The operations left a legacy of radioactive and hazardous waste contamination. Cleanup operations began in earnest in 1995. As part of closure, all radioactive and hazardous waste will be shipped from Rocky Flats to waste disposal sites in other states. No waste will be permanently stored or disposed of on site. Currently, all low-level radioactive waste leaving Rocky Flats is transported by truck. As the Rocky Flats Closure Project Cleaning up Rocky Flats will return thousands of acres to the citizens of Colorado. The nears completion, demolition of former site will become a national wildlife refuge. manufacturing buildings signifi cantly increases the volume of low-level radioactive waste. To improve effi ciency and worker safety, the project will use railcars to ship very low-level waste to the Envirocare disposal facility in Utah. Using rail may eliminate as many as 5,000 truck shipments. Background The complex job of cleaning up and closing down Rocky Flats involves removing massive quantities of radioactive waste. To date, after nine years of shipping, Rocky Flats has safely shipped approximately 260,000 cubic meters (65 percent) of the projected 400,000 cubic meters of radioactive waste that will be generated during closure. -

Eaber Working Paper Series

EAST ASIAN BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH EABER WORKING PAPER SERIES Paper No. 104 ASSESSING THE COMPETITIVENESS OF THE SUPPLY SIDE RESPONSE TO CHINA’S IRON ORE DEMAND SHOCK LUKE HURST CRAWFORD SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND GOVERNMENT, AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY [email protected] JEL Codes: F13, L16, L11 EABER SECRETARIAT CRAWFORD SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND GOVERNMENT ANU COLLEGE OF ASIA AND THE PACIFIC THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY © East Asian Bureau of Economic Research. CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA Abstract This article examines the scale of China’s demand shock and the supply-side reaction in established and fringe iron ore regions. It outlines the short-run constraints on supply expansion and explores the supply-side response to understand whether the long-run iron ore market adjustment has been competitive, or influenced by strategic supply and price interventions by incumbent producers. Keywords: iron ore; market adjustment; competition; oligopoly 2 Introduction1 China’s demand for iron ore already dwarfs established markets in Japan and the rest of Asia. The massive scale and fast pace of China’s demand growth has required significant adjustment to the patterns of trade in the global iron ore market and supported a large and sustained price rise from US$13.83 in 2003 to US$128.87/t in 2012, after peaking at US$187.18/t in 2011. At the start of the iron ore industry consolidation period in 1990 the Big 3 (Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton, and Vale) accounted for 31.4 per cent of global supply. In 2003—the early stages of China’s demand boom—iron ore industry consolidation had led to the Big 3 accounting for 65.8 per cent of global production. -

Asset Recovery Handbook

Asset Recovery Handbook eveloping countries lose billions each year through bribery, misappropriation of funds, Dand other corrupt practices. Much of the proceeds of this corruption find “safe haven” in the world’s financial centers. These criminal flows are a drain on social services and economic development programs, contributing to the impoverishment of the world’s poorest countries. Many developing countries have already sought to recover stolen assets. A number of successful high-profile cases with creative international cooperation has demonstrated Asset Recovery Handbook that asset recovery is possible. However, it is highly complex, involving coordination and collaboration with domestic agencies and ministries in multiple jurisdictions, as well as the A Guide for Practitioners, Second Edition capacity to trace and secure assets and pursue various legal options—whether criminal confiscation, non-conviction based confiscation, civil actions, or other alternatives. A Guide for Practitioners, This process can be overwhelming for even the most experienced practitioners. It is exception- ally difficult for those working in the context of failed states, widespread corruption, or limited Jean-Pierre Brun resources. With this in mind, the Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) Initiative has developed and Anastasia Sotiropoulou updated this Asset Recovery Handbook: A Guide for Practitioners to assist those grappling with Larissa Gray the strategic, organizational, investigative, and legal challenges of recovering stolen assets. Clive Scott A practitioner-led project, the Handbook provides common approaches to recovering stolen assets located in foreign jurisdictions, identifies the challenges that practitioners are likely to Kevin M. Stephenson encounter, and introduces good practices. It includes examples of tools that can be used by Second Edition practitioners, such as sample intelligence reports, applications for court orders, and mutual legal assistance requests. -

United States District Court Southern District of New York

R-0047 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK Rio Tinto plc, Plaintiff, Civil Action No. v. Vale, S.A., Benjamin Steinmetz, BSG COMPLAINT Resources Limited, BSG Resources (Guinea) Ltd. aka BSG Resources Guinée Ltd, BSGR Guinea Ltd. BVI, BSG Resources Guinée JURY TRIAL DEMANDED SARL aka BSG Resources (Guinea) SARL aka VBG-Vale BSGR Guinea, Frederic Cilins, Michael Noy, Avraham Lev Ran, Mamadie Touré, and Mahmoud Thiam, Defendants. For its Complaint, Plaintiff Rio Tinto plc (“Rio Tinto”) alleges as follows: I. INTRODUCTION 1. This is a case about the theft of Rio Tinto’s valuable mining rights by the Defendants through a scheme in violation of the Racketeer Influence and Corrupt Organizations Act (“RICO”), hatched and substantially executed in the United States. The U.S.-based enterprise’s ultimate target was Rio Tinto’s mining concession in the Simandou region of southeast Guinea. Simandou is one of the most valuable iron ore deposits in the world, estimated to be worth billions of dollars. At the time Defendants devised their fraudulent scheme, Rio Tinto had spent eleven years and hundreds of million of dollars developing mining operations at Simandou and expected it to yield substantial profits into the future. 2. At the heart of the RICO scheme was Defendant Vale, S.A. (“Vale”), an international mining company whose American Depository Receipts (ADRs) are among the most-heavily traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Beginning in August 2008, Vale entered into discussions with Rio Tinto to purchase some of the Simandou asset. The Rio Tinto-Vale negotiations began in person with two meetings in New York in November 2008, during which Rio Tinto provided Vale with highly confidential and proprietary information regarding Simandou. -

Analysis and Prospects of Container and Rail Transport

MATEC Web of Conferences 329, 01014 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/202032901014 ICMTMTE 2020 Analysis and prospects of container and rail transport Sergey Vakulenko1,*, Pyotr Kurenkov1, Dmitry Romensky1 , Kirill Kalinin1, and Jozef Gašparík2 1Department of Transport business management and intelligent systems, Russian University of Transport, Moscow, Obraztsova str., 9, building 9, 127994. Russia 2Faculty of Operation and Economics of Transport and Communications, Zilina, Univerzitná 8215/1, 010 26, Republic of Slovakia Abstract. The article studies the main trends in the market of container transportation in rolling stock of various types, considers the process of transporting large-capacity containers in open wagons. The operational and economic aspects of removing administrative restrictions on the implementation of this type of transportation are noted. The dynamics of rental rates for rental of gondola cars and platforms in 2019-2020 is present. The summary characteristics of the gondola car fleet and fitting platforms on the Russian Railways network have been study. The analysis of the market share of the largest owners of gondola cars and fitting platforms was carry out. The advantages and disadvantages of using the technology of container transportation in open wagons are list. Solutions are propose to create a competitive environment in the container transportation segment of the transport services market. 1 Introduction Currently, containers are transport on fitting platforms, but theoretically, according to international rules, they can also be transport in open wagons: 40-feet - horizontally per piece, 20-feet - two each, and empty 20-feet - even three. From December 1, 2014, the local technical conditions (LTC) for the placement and fastening of universal containers in gondola cars with unloading hatches were cancel. -

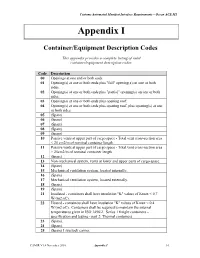

Appendix I – Container/Equipment Description Codes

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix I Container/Equipment Description Codes This appendix provides a complete listing of valid container/equipment description codes. Code Description 00 Openings at one end or both ends. 01 Opening(s) at one or both ends plus "full" opening(s) on one or both sides. 02 Opening(s) at one or both ends plus "partial" opening(s) on one or both sides. 03 Opening(s) at one or both ends plus opening roof. 04 Opening(s) at one or both ends plus opening roof, plus opening(s) at one or both sides. 05 (Spare) 06 (Spare) 07 (Spare) 08 (Spare) 09 (Spare) 10 Passive vents at upper part of cargo space - Total vent cross-section area < 25 cm2/m of nominal container length. 11 Passive vents at upper part of cargo space - Total vent cross-section area > 25cm2/m of nominal container length. 12 (Spare) 13 Non-mechanical system, vents at lower and upper parts of cargo space. 14 (Spare) 15 Mechanical ventilation system, located internally. 16 (Spare) 17 Mechanical ventilation system, located externally. 18 (Spare) 19 (Spare) 21 Insulated - containers shall have insulation "K" values of Kmax < 0.7 W/(m2.oC). 22 Heated - containers shall have insulation "K" values of Kmax < 0.4 W/(m2.oC). Containers shall be required to maintain the internal temperatures given in ISO 1496/2. Series 1 freight containers – specification and testing - part 2: Thermal containers. 23 (Spare). 24 (Spare). 25 (Spare) Livestock carrier. CAMIR V1.4 November 2010 Appendix I I-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Code Description 26 (Spare) Automobile carrier. -

An Inventory of Its Freight Car Specifications at the Minnesota

NP Mechanical Dept. Freight Car Specifications Spec. No. Description Dates C-O Hicks Double Deck Car 1886 C-l Standard Stock Car Body 1885 C-2 Standard Fruit Car 1890 c-3 Flat Bottom Gondola 1905 C-4 Standard Box Car 1883 c-21 Standard Box Car - Roller Bearing 1886-1889 C-22 Standard Caboose Truck 1888-1890 C-23 Standard Caboose Car Body 1886 C-23 40' flat car - S.P.&D. R.R. C-24 Boarding Cars C-25 Roller Bearing Iron Truck C-27 Swing Motion Roller Bearing Truck c-28 Truck No. 3 C-35 Standard Stock Car Body 1888 C-65 Refrigerator Car 1888 C-67 Roller Bearing Truck 1889 C-68 Truck 1889 C-74 Flat Car 1890 C-82 Refrigerator Car 1890 C-85 Wheels 1890 C-1l8 Street's Stable Car 1892 C-120 Stock Car Truck 1892 C-122 34' Box Car 1892 C-133 41' Flat Car 1892 C-135 Roller Bearing Truck 1892 C-139 Roller Bearing Truck 1892 C-141 36' Box Car 1892 C-144 36' Stock Car 1892 C-146 36' Flat Car 1893 C-148 Roller Bearing Stock Car Truck 1893 C-155 Truck, 4" x 7" Journal 1893 C-163 41' Flat Car 1894 C-169 37' Box Car 1895 C-171 Metal Frame Truck with Roller Bearing 1895 C-173 42' Box Car 1895 C-182 Bolsters and spring seats 1896 C-183 Bolsters and spring seats 1897 F-4 42' Hart Convertible 1918 F-5 30' Twin Hopper 1898 F-6 40' Box Car 1906 F-8 41' Flat Car 1895 F-9 Rubber gaskets on doors 1889 F-I0 33'8" Box Car undated F-ll Low roller bearing truck 1900 F-13 36' Box Car 1900 F-14 32' Twin Hopper Coal Car 1900 F-15 22' Caboose undated F-16 80,000-lb. -

Natural Resources and China's Development

SPECIAL REPORT FUELLING THE DRAGON Natural resources and China’s development August 2012 Brenthurst Report Fuelling the Dragon COVER.indd 3 2012/08/13 5:16 PM FUELLING THE DRAGON Natural resources and China’s development The Brenthurst Contents Foundation Abstract .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 Prefaces .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 President John A Kufuor; Prime Minister Raila Odinga; H.E. Mr Erastus Mwencha; The Hon Julie Bishop MP; Senator the Hon Bob Carr Introduction.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 Greg Mills, Terence McNamee and Peter Jennings China’s growth and its impact on resource demand and the iron ore trade .. .. .. .. 11 Peter Drysdale and Luke Hurst Africa and China: between debunking and disaggregation .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 40 Greg Mills Chinese traders: the opaque underbelly of China’s presence in Africa ��������������������������������� 53 Terence McNamee China and Latin American resources – some trends and implications .. .. .. .. .. .. 56 Patrick Esnouf Conclusion .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 66 Greg Mills, Alberto Trejos and Peter Jennings Published in August 2012 by: The Brenthurst Foundation E Oppenheimer & Son (Pty) Ltd PO Box 61631, Johannesburg 2000, South Africa Tel +27–(0)11 274–2096 · Fax +27–(0)11 274–2097 www.thebrenthurstfoundation.org All rights reserved. The material in this publication may not be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior permission of the publisher. Short extracts may be quoted, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Layout and design by Sheaf Publishing, Benoni. Brenthurst Report Fuelling the Dragon.indd 1 2012/08/13 5:15 PM FUELLING THE DRAGON: NatURAL resoUrces and CHINA'S DEVelopMENT Abstract From 17 to 19 May 2012, the Australian Strategic Policy but China’s current appetite for resources will eventually Institute and the Johannesburg-based Brenthurst abate – and that could happen with cruel suddenness. -

Equipment Specifications

EQUIPMENT SPECIFICATIONS cn.ca/equipment AUTOMOTIVE Vehicle Parts These cars are specially designed and equipped to carry vehicle parts. The largest, with a capacity of over 10,000 cubic feet, have doors opening to 20 feet for convenient loading and unloading. CANADIAN NATIONAL CNA 795008 AUTO PARTS BOXCAR PARTS AUTO AUTOMOTIVE / VEHICLE PARTS / VEHICLE PARTS / AUTOMOTIVE AUTO PARTS BOXCAR Car Description Car Series Load Capacity Door Size Inside Dimensions Tons Tonnes Cu. Ft. m3 Width Height Length Width Height Auto Parts Boxcar (60 ft.) DTI 25900-25935 77-84 7,100 201 201 16' 0" 12' 8" 60' 9" 9' 2" 12' 9" GTW 125017-125304 76-84 6,000 170 170 16' 0" 10' 8" - 10' 9" 59' 7" - 60' 8" 9' 2" 11' 2" GTW 306839-306916 62-64 6,222-6,347 176-180 176-180 10' 0" 10' 11" - 11' 3" 60' 8" - 60' 9" 9' 2" - 9' 4" 11' 2" - 11' 4" GTW 375550-376005 78-84 6,347-6,650 180-188 180-188 16' 0" 11' 0" 59' 7" - 60' 9" 9' 1" - 9' 2" 11' 6" - 11' 7" GTW 384000-384699 16-83 7,373-7,596 209-215 209-215 10' 0" - 16' 0" 12' 4" - 12' 9" 60' 9" 9' 1" - 9' 2" 12' 10" - 13' 2" CNA 799309-799729 62-81 6,200-6,636 176-188 176-188 10' 0" - 16' 1" 10' 11" - 11' 3" 60' 8" - 60' 9" 9' 2" - 9' 4" 11' 5" - 11' 7" Auto Parts Boxcar (86 ft.) DTI 26017-26897 48-68 10,000 283 283 20' 0" 12' 9" 86' 6" 9' 2" 12' 9" GTW 105702-105773 48-69 10,000 283 283 20' 0" 12' 9" 86' 6" 9' 2" 12' 9" GTW 126000-127134 46-71 10,000 283 283 20' 0" 12' 9" 84' 2" - 86' 6" 9' 2" 12' 9" GTW 305700-306573 49-72 10,000 283 283 20' 0" 12' 9" 84' 2" - 86' 6" 9' 2" 12' 9" GTW 378001-378250 37-45 10,000 283 283 20' 0" 12' 9" 86' 6" 9' 2" 12' 9" IC/ICG 680004-680137 68-70 10,000-10,151 283-287 283-287 20' 0" 12' 9" 86' 6" 9' 2" 12' 9" CNA 795000-795403 44-72 10,000-10,600 283-300 283-300 20' 0" 12' 9" 86' 6" 9' 2" 12' 3" - 12' 9" AUTOMOTIVE Finished Vehicles The workhorse of the industry, these enclosed double-deck auto carriers are used to transport vans and trucks as well as cars to CN's network of auto compounds. -

New Designs of Wagon

New Design of Wagons AK Khosla Jindal Rail Infrastructure Ltd. Presentation Outline Wagon Holding on IR Type of Wagons on IR Max Moving Dimensions & Fixed structures Design Criteria Drivers for New Wagon Designs Brief on Jindal Rail Infrastructure Ltd. Presentation Outline Wagon Holding on IR Type of Wagons on IR Max Moving Dimensions & Fixed structures Design Criteria Drivers for New Wagon Designs Brief on Jindal Rail Infrastructure Ltd. Wagon Holding on Indian Railways TYPE OF WAGON WAGONS TOTAL QTY. OPEN WAGON BOXN,BOXNHS,BOXNHL,BOXNLW,BOY,BOST,BO 1,37,360 STHSM2,BOXNLW, BOXNS COVERED WAGON BCNA, BCNHL, BCNAHS 70,239 FLAT WAGON BFNS,BRNA,BRN22.9,BRHNEHS, 11,694 HOPPER WAGON BOBYN,BOBYN22.9,BOBRN,BOBRNHS,BCFC,BO 25,196 BRNHSM1,BOBRNAL,BOBSN BRAKE VAN WAGON BVZI,BVZC,BVCM 5,982 TANK WAGON BTPN,BTPGLN,BTFLN 14,066 CONTAINER WAGON BLC/BLL 14,891 SPECIAL PURPOSE BCACBM (A-CAR/B-CAR), BOM, BWT & Others 6,780 WAGON Total 2,86,208 Presentation Outline Wagon Holding on IR Wagon Types on IR Max Moving Dimensions & Fixed structures Design Criteria Drivers for New Wagon Designs Brief on Jindal Rail Infrastructure Ltd. Wagon Types on Indian Railways OPEN WAGONS BOXNHL WAGON BOXNHS WAGON SALIENT FEATURE BOXNHL BOXNHS BOXNS BOY Material of Construction IRS M44, CRF IS 2062 E250 IS 2062 E450 BR IS:2062E250 A CU & section A CU CU IRSM41 Type of Commodity Coal Coal Coal minerals/ore Loading Top loading Top loading Top loading Top loading Unloading Side doors & Side doors & Tippling operation Or Grabber Tippling Grabber Grabber operation Length over head stock (mm) 10034 9784 9784 11000 Length over couplers (mm) 10963 10713 10713 11929 Length inside (mm) 10034 9784 9784 10990 Width inside/Width Overall (mm) 3022/3250 2950/3200 3111/3135 2924/3134 Height inside/Height(max.)from RL. -

Rolling Stock: Locomotives and Rail Cars

Rolling Stock: Locomotives and Rail Cars Industry & Trade Summary Office of Industries Publication ITS-08 March 2011 Control No. 2011001 UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION Karen Laney Acting Director of Operations Michael Anderson Acting Director, Office of Industries This report was principally prepared by: Peder Andersen, Office of Industries [email protected] With supporting assistance from: Monica Reed, Office of Industries Wanda Tolson, Office of Industries Under the direction of: Deborah McNay, Acting Chief Advanced Technology and Machinery Division Cover photo: Courtesy of BNSF Railway Co. Address all communication to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 www.usitc.gov Preface The United States International Trade Commission (USITC) has initiated its current Industry and Trade Summary series of reports to provide information on the rapidly evolving trade and competitive situation of the thousands of products imported into and exported from the United States. Over the past 20 years, U.S. international trade in goods and services has risen by almost 350 percent, compared to an increase of 180 percent in the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), before falling sharply in late 2008 and 2009 due to the economic downturn. During the same two decades, international supply chains have become more global and competition has increased. Each Industry and Trade Summary addresses a different commodity or industry and contains information on trends in consumption, production, and trade, as well as an analysis of factors affecting industry trends and competitiveness in domestic and foreign markets. This report on the railway rolling stock industry primarily covers the period from 2004 to 2009, and includes data for 2010 where available.