Natural Hybridization Within the Genus Quercus L Bs Rushton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chestnut Oak Botanical/Latin Name Quercus Montana

Chestnut Oak Botanical/Latin name Quercus Montana Chestnut Oak owes its name to its leaves, 4”-6” long, looking like those of the American Chestnut. It is a species of oak in the white oak group native to eastern U.S. Predominantly a ridge-top tree in hardwood forests. Also called Mountain Oak or Rock Oak because it grows in dry rocky habitats, sometimes even around large rocks. As a consequence of its dry habitat and harsh ridge-top exposure, it is not usually large, 59’–72’ tall; specimens growing in better conditions however can become large, up to 141’. It is a long-lived tree, with high-quality timber when well-formed. The heavy, durable, close-grained wood is used for fence posts, fuel, railroad ties and tannin. Saplings are easier to transplant than many other oaks because the taproot of the seedling disintegrates as the tree grows, and the remaining roots form a dense mat about three feet deep. It is monoecious, having pollen-bearing catkins in mid-spring that fertilize the inconspicuous female flowers on the same tree. It reproduces from seed as well as stump sprouts. The 1”-1-1/2” long acorns mature in one growing season, are among the largest of native American oaks and are a valuable wildlife food. Acorns are produced when a tree grown from seed is about 20 years of age, but sprouts from cut stumps can produce acorns in as little as three years after cutting. Extensive confusion between the chestnut oak (Q. montana) and the swamp chestnut oak (Quercus michauxii) has historically occurred. -

Appendix 2: Plant Lists

Appendix 2: Plant Lists Master List and Section Lists Mahlon Dickerson Reservation Botanical Survey and Stewardship Assessment Wild Ridge Plants, LLC 2015 2015 MASTER PLANT LIST MAHLON DICKERSON RESERVATION SCIENTIFIC NAME NATIVENESS S-RANK CC PLANT HABIT # OF SECTIONS Acalypha rhomboidea Native 1 Forb 9 Acer palmatum Invasive 0 Tree 1 Acer pensylvanicum Native 7 Tree 2 Acer platanoides Invasive 0 Tree 4 Acer rubrum Native 3 Tree 27 Acer saccharum Native 5 Tree 24 Achillea millefolium Native 0 Forb 18 Acorus calamus Alien 0 Forb 1 Actaea pachypoda Native 5 Forb 10 Adiantum pedatum Native 7 Fern 7 Ageratina altissima v. altissima Native 3 Forb 23 Agrimonia gryposepala Native 4 Forb 4 Agrostis canina Alien 0 Graminoid 2 Agrostis gigantea Alien 0 Graminoid 8 Agrostis hyemalis Native 2 Graminoid 3 Agrostis perennans Native 5 Graminoid 18 Agrostis stolonifera Invasive 0 Graminoid 3 Ailanthus altissima Invasive 0 Tree 8 Ajuga reptans Invasive 0 Forb 3 Alisma subcordatum Native 3 Forb 3 Alliaria petiolata Invasive 0 Forb 17 Allium tricoccum Native 8 Forb 3 Allium vineale Alien 0 Forb 2 Alnus incana ssp rugosa Native 6 Shrub 5 Alnus serrulata Native 4 Shrub 3 Ambrosia artemisiifolia Native 0 Forb 14 Amelanchier arborea Native 7 Tree 26 Amphicarpaea bracteata Native 4 Vine, herbaceous 18 2015 MASTER PLANT LIST MAHLON DICKERSON RESERVATION SCIENTIFIC NAME NATIVENESS S-RANK CC PLANT HABIT # OF SECTIONS Anagallis arvensis Alien 0 Forb 4 Anaphalis margaritacea Native 2 Forb 3 Andropogon gerardii Native 4 Graminoid 1 Andropogon virginicus Native 2 Graminoid 1 Anemone americana Native 9 Forb 6 Anemone quinquefolia Native 7 Forb 13 Anemone virginiana Native 4 Forb 5 Antennaria neglecta Native 2 Forb 2 Antennaria neodioica ssp. -

Announcing the SMA Urban Tree of the Year: Chestnut Oak

Announcing the SMA Urban Tree of The Year: Chestnut Oak The 2017 SMA Urban Tree of the Year is native to much of the Eastern United States. Hikers from New York to Tennessee who ascend to dry ridges will often see the deeply furrowed, blocky barked trunks of chestnut oak (Quercus mon- tana) (syn. Q. prinus). The bark is so distinctive, it may be the only ID feature one needs. There’s growing interest in using chestnut oak in the urban environment because it is pH-adaptable, handles dry soils and periods of drought, has a beautiful mature form, requires mini- mal pruning, and tends to be free of major pests and diseases. The common name “chestnut oak” owes to the leaves looking like those of American chestnut (Castanea dentata) and indeed both are members of the beech family, Fagaceae. Other com- mon names for chestnut oak include rock oak, rock chestnut oak, or mountain oak—referring to its customary sighting in dry, rocky soils on ridgetops, where it has a competitive advantage. Chestnut oak acorn • Photo by Keith Kanoti, Maine Forest However, if chestnut oak is open-grown in the moist, well- Service, Bugwood.org drained soil that all trees dream about, it will be significantly bigger than its scrappy ridgetop cousins. Typically it reaches 50 to 70 feet (15 to 21 m) tall and almost as wide. It’s hardy in USDA Zones 4 to 8 and prefers full sun. Dublin, Ohio Forestry Assistant Jocelyn Knerr nominated the tree. “We started using chestnut oak in Dublin in 2009 as a street tree,” she says. -

Botanical Name Common Name

Approved Approved & as a eligible to Not eligible to Approved as Frontage fulfill other fulfill other Type of plant a Street Tree Tree standards standards Heritage Tree Tree Heritage Species Botanical Name Common name Native Abelia x grandiflora Glossy Abelia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes White Forsytha; Korean Abeliophyllum distichum Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Abelialeaf Acanthropanax Fiveleaf Aralia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes sieboldianus Acer ginnala Amur Maple Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus parviflora Bottlebrush Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus pavia Red Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Alnus incana ssp. rugosa Speckled Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Alnus serrulata Hazel Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier humilis Low Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier stolonifera Running Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes False Indigo Bush; Amorpha fruticosa Desert False Indigo; Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No No Not eligible Bastard Indigo Aronia arbutifolia Red Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia melanocarpa Black Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia prunifolia Purple Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Groundsel-Bush; Eastern Baccharis halimifolia Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Baccharis Summer Cypress; Bassia scoparia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Burning-Bush Berberis canadensis American Barberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Common Barberry; Berberis vulgaris Shrub, Deciduous No No No No Not eligible European Barberry Betula pumila -

Mt. Salvation Tree Inventory Narrative

Mt. Salvation tree inventory narrative. Introduction* Vincent Verweij, Urban Forester of the Department of Parks and Recreation conducted this tree survey on June 17, 2016 in response to a request from the Historic Preservation Program of Arlington County. The tree survey encompassed the parcel that comprises the study area. All trees larger than three inches Diameter at Breast Height (DBH) were inventoried. The inventory was carried out on private property only, disregarding street trees or trees in the adjacent properties. The inventory included 33 individual trees, although smaller trees exist on site. All trees are listed and numbered in an inventory on the attached map, and in detail in the appendix of this narrative. Species and size composition Mt. Salvation is a property with a moderate diversity of tree species. The trees on site are mostly native species, with one exception, the bird cherry. The makeup of native species include high value species, such as Figure 1: One of the large trees in the cemetery chestnut oak and hickory, as well as early succession species with great wildlife value, such as black locust and black cherry. Many of the trees in the cemetery are of old age and large size, with one tree reaching Notable tree status. No evergreens exist on site. The overwhelming majority of the trees on site are naturally- grown trees. This property has trees that may age back to the late 1800s, most likely around the 1860s, when many trees were cut down in Arlington County for the Civil War effort. A small stand of more natural forest patch exists on site, as well, with sassafras and black cherry dominating. -

An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks

Article An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus): Review of the Contribution of Phylogenomic Data to Biogeography and Species Diversity Paul S. Manos 1,* and Andrew L. Hipp 2 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, 330 Bio Sci Bldg, Durham, NC 27708, USA 2 The Morton Arboretum, Center for Tree Science, 4100 Illinois 53, Lisle, IL 60532, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The oak flora of North America north of Mexico is both phylogenetically diverse and species-rich, including 92 species placed in five sections of subgenus Quercus, the oak clade centered on the Americas. Despite phylogenetic and taxonomic progress on the genus over the past 45 years, classification of species at the subsectional level remains unchanged since the early treatments by WL Trelease, AA Camus, and CH Muller. In recent work, we used a RAD-seq based phylogeny including 250 species sampled from throughout the Americas and Eurasia to reconstruct the timing and biogeography of the North American oak radiation. This work demonstrates that the North American oak flora comprises mostly regional species radiations with limited phylogenetic affinities to Mexican clades, and two sister group connections to Eurasia. Using this framework, we describe the regional patterns of oak diversity within North America and formally classify 62 species into nine major North American subsections within sections Lobatae (the red oaks) and Quercus (the Citation: Manos, P.S.; Hipp, A.L. An Quercus Updated Infrageneric Classification white oaks), the two largest sections of subgenus . We also distill emerging evolutionary and of the North American Oaks (Quercus biogeographic patterns based on the impact of phylogenomic data on the systematics of multiple Subgenus Quercus): Review of the species complexes and instances of hybridization. -

Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping Chesapeake Bay Watershed Acknowledgments

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping Chesapeake Bay Watershed Acknowledgments Contributors: Printing was made possible through the generous funding from Adkins Arboretum; Baltimore County Department of Environmental Protection and Resource Management; Chesapeake Bay Trust; Irvine Natural Science Center; Maryland Native Plant Society; National Fish and Wildlife Foundation; The Nature Conservancy, Maryland-DC Chapter; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center; and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office. Reviewers: species included in this guide were reviewed by the following authorities regarding native range, appropriateness for use in individual states, and availability in the nursery trade: Rodney Bartgis, The Nature Conservancy, West Virginia. Ashton Berdine, The Nature Conservancy, West Virginia. Chris Firestone, Bureau of Forestry, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Chris Frye, State Botanist, Wildlife and Heritage Service, Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Mike Hollins, Sylva Native Nursery & Seed Co. William A. McAvoy, Delaware Natural Heritage Program, Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Mary Pat Rowan, Landscape Architect, Maryland Native Plant Society. Rod Simmons, Maryland Native Plant Society. Alison Sterling, Wildlife Resources Section, West Virginia Department of Natural Resources. Troy Weldy, Associate Botanist, New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Graphic Design and Layout: Laurie Hewitt, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office. Special thanks to: Volunteer Carole Jelich; Christopher F. Miller, Regional Plant Materials Specialist, Natural Resource Conservation Service; and R. Harrison Weigand, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Maryland Wildlife and Heritage Division for assistance throughout this project. -

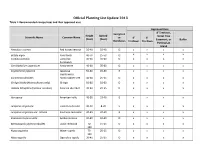

Planting List Update 2013 Table 1: Recommended Canopy Trees and Their Approved Uses

Official Planting List Update 2013 Table 1: Recommended canopy trees and their approved uses Approved Uses 8' Treelawn, Evergreen Height Spread Street Tree Scientific Name Common Name or 4' 6' (Feet) (Feet) Easement, or Buffer Deciduous Treelawn Treelawn Parking Lot Island Aesculus x carnea Red horsechestnut 30-40 30-40 D x x x x Betula nigra River birch 40-70 25-50 D x x x x Carpinus betulus European 40-60 30-40 D x x x x hornbeam Cercidiphyllum japonicum Katsuratree 40-60 35-60 D x x x x Cryptomeria japonica Japanese 50-60 20-30 E x x x x cryptomeria Eucommia ulmoides Hardy rubber tree 40-60 25-35 D x x x x Ginkgo biloba (Male cultivars only) Ginkgo 50-80 50-60 D x x x x Halesia tetraptera (Halesia carolina) Carolina silverbell 30-40 20-35 D x x x x Ilex opaca American holly 40-50 18-40 E x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern red cedar 40-50 8-20 E x x x x Juniperus virginiana var. siliciola Southern red cedar 30-45 20-30 E x x x x Koelreuteria paniculata Goldenraintree 30-40 30-40 D x x x x Metasequoia glyptostroboides Dawn redwood 70- 15-25 D x x x x 100 Nyssa aquatica Water tupelo 75- 25-35 D x x x x 100 Nyssa ogeche Ogeechee tupelo 30-45 25-35 D x x x x Nyssa sylvatica Black gum 20-30 D x x x x 30-70 Ostrya carpinifolia Hophornbeam 50-65 25-35 D x x x x Ostrya virginiana American 25-40 20-40 D x x x x hophornbeam Parrotia persica Persian ironwood 20-40 20-35 D x x x x Quercus robur 'fastigiata' Upright English oak 50-60 10-18 D x x x x 40-50 40-50 D x x x x Sapindus drummondii Western soapberry Sassafras albidium Sassafras 30-60 25-40 D x x x x Taxodium ascendens (Taxodium Pondcypress 70-80 15-20 D x x x x distichum var. -

The Distribution of the Genus Quercus in Illinois: an Update

Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science received 3/19/02 (2002), Volume 95, #4, pp. 261-284 accepted 6/23/02 The Distribution of the Genus Quercus in Illinois: An Update Nick A. Stoynoff Glenbard East High School Lombard, IL 60148 William J. Hess The Morton Arboretum Lisle, IL 60532 ABSTRACT This paper updates the distribution of members of the black oak [section Lobatae] and white oak [section Quercus] groups native to Illinois. In addition a brief discussion of Illinois’ spontaneously occurring hybrid oaks is presented. The findings reported are based on personal collections, herbarium specimens, and published documents. INTRODUCTION The genus Quercus is well known in Illinois. Although some taxa are widespread, a few have a limited distribution. Three species are of “special concern” and are listed as either threatened (Quercus phellos L., willow oak; Quercus montana Willd., rock chestnut oak) or endangered (Quercus texana Buckl., Nuttall’s oak) [Illinois Endangered Species Pro- tection Board 1999]. The Illinois Natural History Survey has dedicated a portion of its website [www.INHS.uiuc.edu] to the species of Quercus in Illinois. A discussion of all oaks from North America is available online from the Flora of North America Associa- tion [http://hua.huh.harvard.edu/FNA/] and in print [Jensen 1997, Nixon 1997, Nixon and Muller 1997]. The National Plant Data Center maintains an extensive online database [http://plants.usda.gov] documenting information on plants in the United States and its territories. Extensive oak data are available there [U.S.D.A. 2001]. During the last 40 years the number of native oak species recognized for Illinois by vari- ous floristic authors has varied little [Tables 1 & 2]. -

Approved Plant List (PDF)

Harford County Approved Plant List April 2019 The Harford County Approved Plant list includes: Permitted tree and plant species for afforestation and reforestation, Permitted street tree species, and Permitted tree and plant species for individual landscaping Please note that not all of the plants on this list are native Maryland species, and therefore not all of the plant species on this list can be used to meet mitigation requirements within the Chesapeake Bay Critical Area. Please refer to the Native Plants list from US Fish and Wildlife, on Harford County’s website, for a comprehensive list of appropriate native plant species to use in the Critical Area. Harford County Approved Plant List April 2019 Plant Species Permitted for Afforestation and Reforestation Trees Scientific Name Common Name Acer negundo Boxelder Acer rubrum Red maple Acer saccharum Sugar maple Acer saccharinum Silver Maple Amelanchier canadensis Shadbush serviceberry Betula lenta Black or Sweet Gum Betula nigra River birch Carpinus caroliniana American hornbeam Carya cordiformis Bitternut hickory Carya glabra Pignut hickory Carya ovata Shagbark hickory Carya tomentosa Mockernut hickory Catalpa speciosa Northern catalpa Celtis occidentalis Common hackberry Cercis canadensis Eastern redbud Cornus florida Flowering dogwood Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur hawthorn Crataegus pruinosa Frosted hawthorn Crataegus punctata Dotted hawthorn Diospyros virginiana Common persimmon Fagus grandifolia American beech Hamamelis virginiana Common witchhazel Juglans cinerea Butternut -

The Allelopathic Influence of Post Oak (Quercus Stellata) on Plant Species in Southern U.S

THE ALLELOPATHIC INFLUENCE OF POST OAK (QUERCUS STELLATA) ON PLANT SPECIES IN SOUTHERN U.S. FORESTS Nicollette A. Baldwin and Michael K. Crosby1 Abstract—Post oak (Quercus stellata) is a commonly occurring tree in the southeastern United States, offering forage and shelter for a variety of wildlife as well as having commercial uses. This species is often planted in parks and urban green-spaces for the shade it offers. Previous studies have found that parts of the plant can be toxic to livestock and that it can inhibit the germination and/or growth of plant species in its vicinity. This study focuses on the allelopathic potential of post oak in an urban, old growth forest. Post oak was selected subsequent to an understory inventory of plant species on a plot established in Marshall Forest in Rome, GA. White oak (Quercus alba) and chestnut oak (Quercus montana) seeds, and muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia) were used to determine if leachates prepared from leaves collected from Post oak inhibit germination and/or growth. Radish (Raphanus sativus) was also used, as it was previously found to be impacted by post oak. Two different concentrations of leachate were prepared and tested on the selected species. The results revealed significant differences in both germination rates and mean sprout lengths between the control (distilled water) and both concentration groups. No significant difference was found between the two concentrations of leaf leachate during the experiment. These results suggest that post oak inhibits the germination rate and sprout length of the tested species. It is important that resource managers understand these relationships in managed landscapes (e.g., parks). -

Southern Garden History Plant Lists

Southern Plant Lists Southern Garden History Society A Joint Project With The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation September 2000 1 INTRODUCTION Plants are the major component of any garden, and it is paramount to understanding the history of gardens and gardening to know the history of plants. For those interested in the garden history of the American south, the provenance of plants in our gardens is a continuing challenge. A number of years ago the Southern Garden History Society set out to create a ‘southern plant list’ featuring the dates of introduction of plants into horticulture in the South. This proved to be a daunting task, as the date of introduction of a plant into gardens along the eastern seaboard of the Middle Atlantic States was different than the date of introduction along the Gulf Coast, or the Southern Highlands. To complicate maters, a plant native to the Mississippi River valley might be brought in to a New Orleans gardens many years before it found its way into a Virginia garden. A more logical project seemed to be to assemble a broad array plant lists, with lists from each geographic region and across the spectrum of time. The project’s purpose is to bring together in one place a base of information, a data base, if you will, that will allow those interested in old gardens to determine the plants available and popular in the different regions at certain times. This manual is the fruition of a joint undertaking between the Southern Garden History Society and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. In choosing lists to be included, I have been rather ruthless in expecting that the lists be specific to a place and a time.