Fairy Lgbtales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ugly Duckling YOU Have an Important Part to Play

The Ugly Duckling STUDY GUIDE THE UGLY DUCKLING BASED ON THE S T O R Y B Y Fairy tales... HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN are types of folk tales. They BY RICHARD GIERSCH usually begin with “Once upon a time...” and end with “...happily ever after.” Also, fairy tales usually have events happening in threes, and involve magic. THE UGLY DUCKLING is a musical written by Richard Giersch, based on the story by Hans Christian Andersen. This program is presented in support of the Folk tales... teaching of the Virginia English Standards of Learning. are short, with a simple plot. They Activities provided support curriculum k-5. have characters representing a characteristic like good or bad and feature events that are AT THE LIBRARY: repeated, especially in threes. Hans Christian Andersen (1805- They are based in fantasy. 1875) was a Danish author best known for writing over 150 children’s stories. Check out the following fairy tales, also by Hans Christian Andersen: The Emperor’s New Clothes Thumbelina The Princess and the Pea YOU Have an Important Part to Play The Steadfast Tin Soldier How to Play Your Part The Fir Tree The Little Mermaid A play is different than television or a movie. The actors are right in front of The Nightingale you and can see your reactions, feel your attention, and hear your laughter Little Match Girl and applause. Watch and listen carefully to understand the story. The story is told by actors and comes to life through your imagination. Page 2 VIRGINIA REPERTORY THEATRE Songs from The Ugly Duckling Plays that include songs are called musicals. -

Who's Afraid of the Brothers Grimm?: Socialization and Politization Through Fairy Tales

Who's Afraid of the Brothers Grimm?: Socialization and Politization through Fairy Tales Jack Zipes The Lion and the Unicorn, Volume 3, Number 2, Winter 1979-80, pp. 4-41 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/uni.0.0373 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/247386 Access provided by University of Mary Washington & (Viva) (19 Sep 2017 17:43 GMT) Who's Afraid of the Brothers Grimm? Socialization and Politization through Fairy Tales Jack Zipes Over 170 years ago the Brothers Grimm began collecting original folk tales in Germany and stylized them into potent literary fairy tales. Since then these tales have exercised a pro- found influence on children and adults alike throughout the western world. Indeed, whatever form fairy tales in general have taken since the original publication of the Grimms' nar- ratives in 1812, the Brothers Grimm have been continually looking over our shoulders and making their presence felt. For most people this has not been so disturbing. However, during the last 15 years there has been a growing radical trend to over- throw the Grimms' benevolent rule in fairy-tale land by writers who believe that the Grimms' stories contribute to the creation of a false consciousness and reinforce an authoritarian sociali- zation process. This trend has appropriately been set by writers in the very homeland of the Grimms where literary revolutions have always been more common than real political ones.1 West German writers2 and critics have come to -

Grimm's Fairy Stories

Grimm's Fairy Stories Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm The Project Gutenberg eBook, Grimm's Fairy Stories, by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm, Illustrated by John B Gruelle and R. Emmett Owen This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Grimm's Fairy Stories Author: Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm Release Date: February 10, 2004 [eBook #11027] Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GRIMM'S FAIRY STORIES*** E-text prepared by Internet Archive, University of Florida, Children, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team Note: Project Gutenberg also has an HTML version of this file which includes the original illustrations. See 11027-h.htm or 11027-h.zip: (http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/1/1/0/2/11027/11027-h/11027-h.htm) or (http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/1/1/0/2/11027/11027-h.zip) GRIMM'S FAIRY STORIES Colored Illustrations by JOHN B. GRUELLE Pen and Ink Sketches by R. EMMETT OWEN 1922 CONTENTS THE GOOSE-GIRL THE LITTLE BROTHER AND SISTER HANSEL AND GRETHEL OH, IF I COULD BUT SHIVER! DUMMLING AND THE THREE FEATHERS LITTLE SNOW-WHITE CATHERINE AND FREDERICK THE VALIANT LITTLE TAILOR LITTLE RED-CAP THE GOLDEN GOOSE BEARSKIN CINDERELLA FAITHFUL JOHN THE WATER OF LIFE THUMBLING BRIAR ROSE THE SIX SWANS RAPUNZEL MOTHER HOLLE THE FROG PRINCE THE TRAVELS OF TOM THUMB SNOW-WHITE AND ROSE-RED THE THREE LITTLE MEN IN THE WOOD RUMPELSTILTSKIN LITTLE ONE-EYE, TWO-EYES AND THREE-EYES [Illustration: Grimm's Fairy Stories] THE GOOSE-GIRL An old queen, whose husband had been dead some years, had a beautiful daughter. -

ALEX: Hello and Welcome to Another Episode of the Princess and the Podcast, the Best Hans Christian Andersen Analysis Podcast out There

ALEX: Hello and welcome to another episode of The Princess and the Podcast, the best Hans Christian Andersen analysis podcast out there. I'm Alex ANA: and I'm Ana. Today we will be talking about Anderson's rocky relationship with royalty through performance and analysis of his tales, "The Princess and the Pea" and "The Emperor's New Clothes". These are two tales that are critical of royalty, which is unusual for Anderson who usually wrote stories which celebrated princes and princesses. ALEX: But before we get to the reading of those two tales, why don't we talk a little bit about Anderson's life and relationship with royalty? ANA: Great idea. Let's start with a bit of background. Anderson grew up poor in the city of Odense, Denmark. His obsession with royalty might have even started at a young age because his father actually believed that they were long lost Royalty. ALEX: Oh, interesting. And yeah, obviously, it remained a theme throughout his life. He surrounded himself with nobility and was always almost ashamed of his poor background, and apparently his rich friends didn't shy away from reminding him of that. ANA: Oh, so that explains why he wrote all these stories like his most famous, "The Little Mermaid". That were sort of royalty positive or lifted up the idea of royalty. But he has as mentioned these two stories that seem to contradict that, which are "The Emperor's New Clothes" and "The Princess and the Pea". ALEX: Yeah, so starting with the Emperor's New Clothes, how does that criticize or make fun of royalty? ANA: Well, to start off, in the story, The emperor is a man who's literally obsessed with clothes and his outfits. -

Gay and Transgender Communities - Sexual And

HOMO-SEXILE: GAY AND TRANSGENDER COMMUNITIES - SEXUAL AND NATIONAL IDENTITIES IN LATIN AMERICAN FICTION AND FILM by Miguel Moss Marrero APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: __________________________________________ Michael Wilson, Chair __________________________________________ Adrienne L. McLean __________________________________________ Robert Nelsen __________________________________________ Rainer Schulte __________________________________________ Teresa M. Towner Copyright 2018 Miguel Moss Marrero All Rights Reserved -For my father who inspired me to be compassionate, unbiased, and to aspire towards a life full of greatness. HOMO-SEXILE: GAY AND TRANSGENDER COMMUNITIES - SEXUAL AND NATIONAL IDENTITIES IN LATIN AMERICAN FICTION AND FILM by MIGUEL MOSS MARRERO BA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS August 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Latin American transgender women and gay men are part of my family. This dissertation is dedicated to them. It would have not been possible without their stories. I want to give my gratitude to my mother, who set an example by completing her doctoral degree with three exuberant boys and a full-time job in mental health. I also want to dedicate this to my father, who encouraged me to accomplish my goals and taught me that nothing is too great to achieve. I want to thank my siblings who have shown support throughout my doctoral degree. I also want to thank my husband, Michael Saginaw, for his patience while I spent many hours in solitude while writing my dissertation. Without all of their support, this chapter of my life would have been meaningless. -

Put Your Money Where Your Heart Is

PUT YOUR MONEY WHERE YOUR HEART IS. We know giving back is an important piece of your financial plan because it’s an important part of our business plan, too. Associated Bank colleagues have volunteered more than 73,000 hours, and 1% of all our profits go back to local charities. So whatever your goals are for giving back to the place you love, our wealth management team will help you fulfill them. AssociatedBank.com/Wealth-Management Associated Bank, N.A. Member FDIC. (9/20) P02003 #MFF2021 #MFF2021 Annual Fund Milwaukee Film began in 2009 as primarily a film festival that occurred for Hello Film Fans! 11 days. Today, we operate 365 days a year as one of the nation’s leading nonprofit institutions dedicated to film, culture, and community. It’s appropriate that, for our first-ever spring Milwaukee We are committed to enriching, educating, and entertaining our community through film Film Festival, the significance of the season is stronger presentations, signature events, and year-round education programs for all ages. Our incredibly than it’s ever been. generous Annual Fund supporters provide us the visionary support we need to fulfill our mission Our world is opening up, and our thoughts are once again wandering and continue to thrive. beyond the confines of anxiety and isolation that have defined the past 14 months. Though we’re not yet to the point of safely welcoming crowds to a packed house at the Oriental Theatre, we can envision a time in the not-too-distant future when that will be happening again. -

HIGHLANDS NEWS-SUN Monday, June 17, 2019

HIGHLANDS NEWS-SUN Monday, June 17, 2019 VOL. 100 | NO. 168 | $1.00 YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1919 An Edition Of The Sun Road names to change at HRMC Changes to come with roundabout By PHIL ATTINGER “Sebring Parkway,” since have what other parts — to “Highlands Avenue,” STAFF WRITER the road is contiguous of the Parkway will soon since that name will be with the existing Parkway have: A roundabout. available. SEBRING — Motorists north of Youth Care Lane. The roundabout is Under Highlands heading south on Sebring Once work is complet- planned for the northern County road-naming Parkway toward U.S. 27 ed on that section of the entrance of the HRMC standards, any roads that at Highlands Regional Parkway — Phase 2 — campus, better known as are directly connected Medical Center may sometime in the next two Medical Center Drive. throughout their length notice some changes years, it will be identical A section of Medical need to have the same soon on road signs. to the existing Parkway. Center Drive will get name, to make them eas- COURTESY PHOTO/HIGHLANDS COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS County commissioners Not only will it have a renamed as it reaches ier to navigate for law en- have approved changes to divided four-lane road into the property — a forcement, fire and emer- Sebring Parkway Phase 2A will install four lanes from Youth road signs on that stretch with a grass median and change approved by the gency medical personnel. Care Lane to DeSoto Road, improving the intersection there of road, to change “South extended turn lanes at Highlands County Board with extra stacking room for right and left turn lanes both on Highlands Avenue” to intersections, it will also of County Commission ROAD | 2A the Parkway and on the cross-streets. -

Fairy Tale Versions~

FAIRY TALES/FOLK TALES Fairy Tales are a type of folktale in which magic plays a great part. Compiled by Sheila Kirven GENERAL Anderson, Hans Christian Steadfast Tin Soldier Juv.A544ste Armstrong, Gerry The magic bagpipe Juv. 788.9 .A735m Browne, Anthony Into the Forest Juv. B882i (Story incorporates elements of familiar tales) Casserley, Anne Roseen Juv. 398.21 .C344r Chapman, Gaynor The Luck Child Juv. 398.21.C466l 1968 De Regniers, Beatrice Little Sister and the Month Brothers Juv. D431Li Schenk The House in the Wood and Other Old Fairy Stories Juv. 398.2.G864h Little Lit: Folklore and Fairy Tale Funnies Juv.398.21.F666 Hennessy, B. G. Once Upon a Time Map Book: Take a Tour Juv.H515o of Six Enchanted Lands (Peter Pan, Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, Jack and then Beanstalk, Aladdin, Snow White) Jacobs, Joseph The buried moon; a tale told by Joseph Jacobs. Juv. 398.21 .J17b Jacobs, Joseph Indian fairy tales Juv.398.2 .J17i 1969 MacDonald, George, The golden key Juv. M135g Matsutani, Miyoko, The crane maiden. Juv. 98.21 .M434c My Storytime Collection of First Favorite tales Juv. 398.2.M995 2002 O’Malley, Kevin Once upon a cool motorcycle dude Juv. O543o (Two classmates try to tell a fairy tale to their class with some imaginative twists to some well-known fairy tale elements!) Oxenbury, Helen. Helen Oxenbury nursery story book. Juv. 398.21 .O98h San Jose, Christine Little Match Girl Juv. 398.21.A544j San Souci, Robert D. White Cat Juv.398.21.SS229w 1990 Singer, Marilyn Follow Follow: A book of Reverso poems Juv.811.54.S617f (Poems -

Exploring Connections Between Efforts to Restrict Same-Sex Marriage and Surging Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2014 Exploring Connections Between Efforts to Restrict Same-Sex Marriage and Surging Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage Rights: Could Efforts to Restrict Gay Rights Help to Explain Increases in Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage? Samuel Everett Christian Dunlop Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dunlop, Samuel Everett Christian, "Exploring Connections Between Efforts to Restrict Same-Sex Marriage and Surging Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage Rights: Could Efforts to Restrict Gay Rights Help to Explain Increases in Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage?" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1785. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1784 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Exploring Connections Between Efforts to Restrict Same-Sex Marriage and Surging Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage Rights: Could Efforts to Restrict Gay Rights Help to Explain Increases in Public Opinion Support for Same-Sex Marriage? by Samuel Everett Christian Dunlop A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Thesis Committee: Kim Williams, Chair Richard Clucas David Kinsella Portland State University 2014 Abstract Scholarly research on the subject of the swift pace of change in support for same-sex marriage has evolved significantly over the last ten years. -

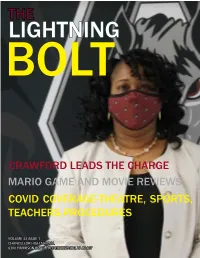

Lightning Bolt

THE LIGHTNING BOLT CRAWFORD LEADS THE CHARGE MARIO GAME AND MOVIE REVIEWS COVID COVERAGE-THEATRE, SPORTS, TEACHERS,PROCEDURES VOLUME 33 iSSUE 1 CHANCELLOR HIGH SCHOOL 6300 HARRISON ROAD, FREDERICKSBURG, VA 22407 1 Sep/Oct 2020 RETIREMENT, RETURN TO SCHOOL, MRS. GATTIE AND CRAWFORD ADVISOR FAITH REMICK Left Mrs. Bass-Fortune is at her retirement parade on June EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 24 that was held to honor her many years at Chancellor High School. For more than three CARA SEELY hours decorated cars drove by the school, honking at Mrs. NEWS EDITOR Bass-Fortune, giving her gifts and well wishes. CARA HADDEN FEATURES EDITOR KAITLYN GARVEY SPORTS EDITOR STEPHANIE MARTINEZ & EMMA PURCELL OP-ED EDITORS Above and Left: Chancellor gets a facelift of decorated doors throughout the school. MIKAH NELSON Front Cover:New Principal Mrs. Cassandra Crawford & Back Cover: Newly Retired HAILEY PATTEN Mrs. Bass-Fortune CHARGING CORNER CHARGER FUR BABIES CONTEST MATCH THE NAME OF THE PET TO THE PICTURE AND TAKE YOUR ANSWERS TO ROOM A113 OR EMAIL LGATTIE@SPOT- SYLVANIA.K12.VA.US FOR A CHANCE TO WIN A PRIZE. HAVE A PHOTO OF YOUR FURRY FRIEND YOU WANT TO SUBMIT? EMAIL SUBMISSIONS TO [email protected]. Charger 1 Charger 2 Charger 3 Charger 4 Names to choose from. Note: There are more names than pictures! Banks, Sadie, Fenway, Bently, Spot, Bear, Prince, Thor, Sunshine, Lady Sep/Oct 2020 2 IS THERE REWARD TO THIS RISK? By Faith Remick school even for two days a many students with height- money to get our kids back Editor-In-Chief week is dangerous, and the ened behavioral needs that to school safely.” I agree. -

The Parkview Pantera

TThehe ParkviewParkview Pantera DECEMBER 2016 NEWS AROUND PHS Volume XLL, Edition I I Toys for Tots gives back to the community that the club accumulates in monetary donations is used to purchase additional toys, which are also sent to the warehouse for distribution. This year on all week- NEWS (2-3) ends through December 17th, JROTC students will be collecting donations in front of several, local Wal- Mart and Kroger stores, according to cadet private Annaliese Mayo, “Some- times, parents can’t afford to buy toys for their kids, and we’re trying to help those FEATURES (5-8) parents out so their kids can have toys too.” Parkview students can also contribute to the cause by donating to the Toys for Tots donation box in the front offi ce. Not everyone can enjoy the festivity of the holidays, Cadet Gunnery Sergeant Samantha Green (left) and Cadet Private Anna Mayo (right) do- and in recognition of such, nate their time to Toys for Tots during the holiday season. (Photo courtesy of Jolie Mayo) JROTC students are working OPINION (9-14) especially hard to ease the By Jenny Nguyen, Copy JROTC helps out in the op- donations through local strain for others who are less Editor erations of the U.S. Marine retail and grocery stores, has fortunate. “[The program] Corps Toys for Tots Pro- successfully expanded their impacts people, and I tell it The Christmas season gram, which serves to collect annual contributions to over to the students all the time. has offi cially come into its and deliver Christmas gifts $70,000. -

Midsummer Storybooks

Description Magic Items Pick 2: Subtract your Popularity from 3 and choose that little coat, pretty, plump, rosy cheeks, youngest, many magic items from the following: smallest, willful, hair of gold, hair of silver, lovely, magic stones (2) Child clad in leaves, hooded, thick brows, humble, joyful, bread crumbs (1) conceited, curly hair, loveable, blue coat, red shoes, horn of waking (1) “All children, except too spoiled, headstrong, polite, frills, patched, little, wooden horse (2) sometimes good, sometimes bad, fond of good lamp of seven kingdoms (1) one, grow up.” things singing quilt (1) - Peter Pan and Wendy, James M. Barrie pan pipes (2) Mundane Life cursed mirror shards (2) Pick 1: treasure map (1) babysitter, paperboy, thief, runaway, foster child, silver knife (1) (magical weapon 1) hacker, volunteer, scout, child singer, child star, little black casket (2) abductee, skateboarder, busker, dog walker, student, wooden sword (2) (magical weapon 2) assistant, urchin, bellhop, dish washer, assembly any wealth 1 trinket line worker, bagger, caretaker, gardener, juvenile delinquent Experience Improve Stats Improvements You are filled with the pure wonder Choose one set: Add +1 to your Courage (maximum of +3). Courage +1, Brawn 0, Cunning +2, Wisdom -2 Add +1 to your Brawn (maximum of +3). and innocence of childhood, for you Courage 0, Brawn +1, Cunning +2, Wisdom -2 Add +1 to your Cunning (maximum of +3). Courage +2, Brawn -2, Cunning +2, Wisdom -1 Add +1 to your Wisdom (maximum of +3). are an eternal child. Tricks and tales Courage -1, Brawn -1, Cunning +2, Wisdom +1 Choose a new Child move.