Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2009, 3/4 (129/130), 425–446

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REGIONAL and LOCAL DEVELOPMENT in TIMES of POLARISATION Re-Thinking Spatial Policies in Europe New Geographies of Europe

NEW GEOGRAPHIES OF EUROPE Edited by THILO LANG AND FRANZISKA GÖRMAR REGIONAL AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT IN TIMES OF POLARISATION Re-Thinking Spatial Policies in Europe New Geographies of Europe Series Editors Sebastian Henn Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Jena, Germany Ray Hudson Durham University Durham, UK Thilo Lang Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography University of Leipzig Leipzig, Germany Judit Timár Hungarian Academy of Sciences Budapest, Hungary Tis series explores the production and reshaping of space from a comparative and interdisciplinary perspective. By drawing on con- temporary research from across the social sciences, it ofers novel insights into ongoing spatial developments within and between the various regions of Europe. It also seeks to introduce new geographies at the edges of the European Union and the interplay with bordering areas at the Mediterranean, African and eastern Asian interfaces of the EU. As a result, this series acts as an important forum for themes of pan-European interest and beyond. Te New Geographies of Europe series welcomes proposals for monographs and edited volumes taking a comparative and interdisciplinary approach to spatial phenomena in Europe. Contributions are especially welcome where the focus is upon novel spatial phenomena, path-dependent processes of socio-economic change or policy responses at various levels throughout Europe. Suggestions for topics also include the relationship between the state and citizens, the idea of fragile democracies, the economics of regional separation, -

The Path to the FAIR HANSA FAIR for More Than 600 Years, a Unique Network HANSA of Merchants Existed in Northern Europe

The path to the FAIR HANSA FAIR For more than 600 years, a unique network HANSA of merchants existed in Northern Europe. The cooperation of this consortium of merchants for the promotion of their foreign trade gave rise to an association of cities, to which around 200 coastal and inland cities belonged in the course of time. The Hanseatic League in the Middle Ages These cities were located in an area that today encom- passes seven European countries: from the Dutch Zui- derzee in the west to Baltic Estonia in the east, and from Sweden‘s Visby / Gotland in the north to the Cologne- Erfurt-Wroclaw-Krakow perimeter in the south. From this base, the Hanseatic traders developed a strong economic in uence, which during the 16th century extended from Portugal to Russia and from Scandinavia to Italy, an area that now includes 20 European states. Honest merchants – Fair Trade? Merchants, who often shared family ties to each other, were not always fair to producers and craftsmen. There is ample evidence of routine fraud and young traders in far- ung posts who led dissolute lives. It has also been proven that slave labor was used. ̇ ̆ Trading was conducted with goods that were typically regional, and sometimes with luxury goods: for example, wax and furs from Novgorod, cloth, silver, metal goods, salt, herrings and Chronology: grain from Hanseatic cities such as Lübeck, Münster or Dortmund 12th–14th Century - “Kaufmannshanse”. Establishment of Hanseatic trading posts (Hanseatic kontors) with common privi- leges for Low German merchants 14th–17th Century - “Städtehanse”. Cooperation between the Hanseatic cit- ies to defend their trade privileges and Merchants from di erent cities in di erent enforce common interests, especially at countries formed convoys and partnerships. -

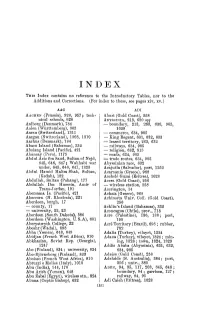

For Index to These, See Pages Xiv, Xv.)

INDEX THis Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables, nor to the Additions and Corrections. (For index to these, see pages xiv, xv.) AAC ADI AAcHEN (Prussia), 926, 957; tech- Aburi (Gold Coast), 258 nical schools, 928 ABYSSINIA, 213, 630 sqq Aalborg (Denmark), 784 - boundary, 213, 263, 630, 905, Aalen (Wiirttemberg), 965 1029 Aarau (Switzerland), 1311 - commerce, 634, 905 Aargau (Switzerland), 1308, 1310 - King Regent, 631, 632, 633 Aarhus (Denmark), 784 - leased territory, 263, 632 Abaco Island (Bahamas), 332 - railways, 634, 905 Abaiaug !Rland (Pacific), 421 - religion, 632, 815 Abancay (Peru), 1175 - roads, 634, 905 Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, Sultan of N ejd, -trade routes, 634, 905 645, 646, 647; Wahhabi war Abyssinian race, 632 under, 645, 646, 647, 1323 Acajutla (Salvador), port, 1252 Abdul Hamid Halim Shah, Sultan, Acarnania (Greece), 968 (Kedah), 182 Acchele Guzai (Eritrea), 1028 Abdullah, Sultan (Pahang), 177 Accra (Gold Coast), 256 Abdullah Ibn Hussein, Amir of - wireless station, 258 Trans-J orrlan, 191 Accrington, 14 Abemama Is. (Pacific), 421 Acha!a (Greece), 968 Abercorn (N. Rhodesia), 221 Achirnota Univ. Col!. (Gold Coast), Aberdeen, burgh, 17 256 - county, 17 Acklin's Island (Bahamas), 332 -university, 22, 23 Aconcagua (Chile), prov., 718 Aberdeen (South Dakota), 586 Acre (Palestine), 186, 188; port, Aberdeen (Washington, U.S.A), 601 190 Aberystwyth College, 22 Acre Territory (Brazil), 698 ; rubber, Abeshr (Wadai), 898 702 Abba (Yemen), 648, 649 Adalia (Turkey), vilayet, 1324 Abidjan (French West Africa), 910 Adana (Turkey), vilayet, 1324; min Abkhasian, Soviet Rep. (Georgia), ing, 1328; town, 1324, 1329 1247 Addis Ababa (Abyssinia), 631, 632, Abo (Finland), 834; university, 834 634, 905 Abo-Bjorneborg (Finland), 833 Adeiso (Gold Coast), 258 Aboisso (French West Africa), 910 Adelaide (S. -

START of the TOUR 1. Riga Gate the Approximate Area Between

START OF THE TOUR 1. Riga Gate The approximate area between Nikolai 7 (a yellow commercial building) and 12 (a green commercial building), see point 1 on the map. The red contour line on the map marks the town and castle walls in the Hanseatic times. The territory of the castle has been marked with diagonal lines, the area that belonged to the town is marked with dots. The contour line is discontinued at the location of the gate. Towers have been marked with circles, half-towers with semi-circles. The map serves an illustrative purpose. A land route, which was in use already in the 13th century, lead to Riga, starting from the Riga Gate and following the coastline. A more direct route would have been through the Cattle Gate (see point 8 on the map), but the road conditions were better when headed through the Riga Gate. This first point gives a great overview of the entire town wall, moat, towers, other gates, main streets and general image of the town. New-Pärnu was surrounded by a rampart. Read more... This rule did not apply to all medieval towns of the region. There were 9 towns, 2 of them big, on the Estonian territory in medieval times: Tallinn and Tartu, plus 7 smaller towns: Rakvere, Paide, Narva, Viljandi, Haapsalu, New- and Old-Pärnu. Four of those, in turn, belonged to the Hanseatic League: Tallinn, Tartu, Viljandi and New-Pärnu. Other medieval small towns that had town walls around them were Viljandi and Narva (Haapsalu was at least partially surrounded). -

Maps Symphony Manual

MANUAL MAPS SYMPHONY 1.0 Copyright 2021 LauterBlauSoft Start ...............................................................................................................3 Wizard ...........................................................................................................3 Select Data ............................................................................................................3 Captions ................................................................................................................5 Chart I ...................................................................................................................6 Chart II ..................................................................................................................7 Export To SVG ................................................................................................8 Appendix .......................................................................................................9 2 START By clicking the gear symbol you open the wizard: WIZARD The wizard opens automatically for the first time. After that, open it by clicking the gear symbol. The wizard consists of 6-8 steps. SELECT DATA 3 Here you can enter the cells (ranges) of the needed values or paste the selections. Example: First select the data values and click "Paste Selection": Then select the countries / states and click "Paste Selection": Note: For Countries enter the correct country name or the iso country code - ISO 3166-2 or ISO 3166-3. For US States insert -

Annual Report 1998

ISSN-0704-4798 Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) Annual Report 1998 Printed and Distributed by: Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization P. 0. Box 638, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Canada B2Y 3Y9 3 Preface This Annual Report for the year 1998 is submitted to the Contracting Parties of NAFO in accordance with the provisions of Article V.4 of the Convention on Future Multilateral Cooperation in the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries. The Report consists of four major parts that reflect the annual activities of NAFO's constituent bodies — the General Council, the Fisheries Commission, the Scientific Council, and the Secretariat as the summary proceedings and decisions through 1998. Full reports of the General Council and Fisheries Commission meetings held during the year are published in a separate edition — "Meeting Proceedings of the General Council and Fisheries Commission for 1998", and the proceedings of the Scientific Council are published in the "Scientific Cmincil Reports, 1998". The Annual Report includes a summary of meetings, scientific, statistical, financial and other appropriate information pertaining to the activities of the Organization and fisheries in the Regulatory Area. L. 1. Chepel Executive Secretary 5 Contents Introduction 9 Map 11 Structure of the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization 13 PART I. Activities of the General Council in 1998 15 List of Meetings 15 Major Documents of the General Council in 1998 17 Working Group on Allocation of Fishing Rights to Contracting Parties of NAFO and Chartering of Vessels Between Contracting Parties, 4-6 March 19 Annex 1. List of Participants 21 Annex 2. Agenda 25 Annex 3. Chairman's Working Paper 26 Working Group on Dispute Settlement Procedures (DSP), 22-24 April 27 Annex L List of Participants 29 Annex 2. -

Network Scan Data

iii iv 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 Indiana Military and Overseas Voter Guide 2004 Table of Contents Section Page Letter from Secretary of State Todd Rokita 2 Military Voters 3 • Definition of a military voter • Who can register to vote • How to register to vote / Extended registration • How to cast a vote Families of Military Voters 6 • Definition of families of military voters • Who can register to vote • How to register to vote / Extended registration • How to cast a vote Overseas Voters 7 • Definition of an overseas voter • Who can register to vote • How to register to vote • How to cast a vote How To Find Information About Elections and Candidates 8 Election Calendar 9 Election Forms (ABS-9, 11, 12, 13, 14 & 15) 11 Contact Information 23 • Federal • State • Political Parties • County • Country and City Calling Codes Voter’s Checklist 38 Federal Registration and Absentee Form (Standard Form 76) Insert Last Revised February 19, 2004 1 Dear Indiana Voter: As Indiana’s chief election officer it is my great pleasure to provide you with the 2004 Indiana Military and Overseas Voter Guide. Within this guide you will find the information and the application forms necessary for you to vote in Indiana elections. My office, the federal government and your local election administrators want to provide you with every opportunity to cast your ballot regardless of where you are currently serving or living in the world. -

SET Bulletin Vol

SET Bulletin Vol. 14, No. 2 July 2013 IFLA Section on Education & Training ISSN 1450-0647 In this Issue: Conference Reports p. 16 Message from the Editor p. 1 New Books p. 19 Conference Calendar p. 26 SET Spotlight Letter from the Chair p. 2 Contact the Section p. 3 Message from the Editor SET News p. 4 Dear colleagues, Who‘s Who: SET SC Member Profiles p. 6 We are looking forward to seeing you in Singapore for the 79th World Library and Information Congress 17–23 August 2013! There you will meet our winners of the IFLA LIS Student Paper Award 2013: Tamara Rhodes from the School of Library and Information Sciences, at North Carolina Central University, USA as first placed winner, and Elina Karioja, Student of Oulu University of Applied Sciences, School of Business and Information Management, Finland, as second placed winner. Please find more information on pages 13–14 and 15–16. There is also an updated list of incoming, re-elected, remaining and outgoing SET SC members, including the candidates for Looking forward to seeing you at the corresponding membership to be elected in the 79th IFLA Singapore SC business meeting, p. 6–7. World Library and Information Congress Please find a timetable of all SET and SET- in Singapore, 17–23 August 2013! related events during the upcoming IFLA Congress on p. 5–6. LIS Education & Training Worldwide The articles on LIS Education and Training coming from Norway, South Carolina, USA, Finally a Doctoral programme in LIS is and Russia show a wide range of various established in Norway p. -

Salt.In.Estoniabrosura.Pdf (1.1 Mib)

Comenius Project ,,SALT OF THE EARTH,, Created by the Romanian Comenius Team from Şcoala Gimnazială Porumbeşti based on materials received from J.V.Veski nim. Maarja Põhikool SALT IN ESTONIA - Jõgeva estonia LINKS http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Hanseatic_League http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tallinn http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tartu http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fellin http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P%C3%A4rnu This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Dorpat (Tartu) Salt in Estonia In the 1280s Dorpat joined Reval (Tallinn) the Hanseatic Salt was a product that was In 1285 the city, then known as League. In medieval times widely used and hence there is a Reval, became the northernmost Tartu was an important trading transportation component that city. member of the Hanseatic League – a comes with salt works and this mercantile and military alliance Pernau can be both land and sea borne. of German-dominated cities in Northern (Pärnu) Europe. The latter In Estonia there are no salt On joining the Hanseatic League, town, then mines, nevertheless the old Reval was a Danish fief, but was sold, known by Hansa route went through the with the rest of northern Estonia, to the the German four Estonian city: Teutonic Order in 1346.. name of Pernau, was a member Reval (Tallinn), Medieval Reval enjoyed a of the Hanseatic League and an Dorpat (Tartu), strategic position at the crossroads of important ice-free harbor. -

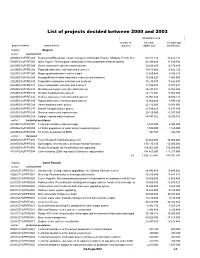

Projects Decided 2000-2003

List of projects decided between 2000 and 2003 amounts in euro number of est. total est.total Ispa project number: projec namet: projects eligible cost contribution country: Bulgaria sector: environment 2000/BG/16/P/PE/002 Regional landfills (group) - waste management:Sozopol, Rousse, Montana, Pernik, Sev 60.577.513 45.433.135 2000/BG/16/P/PE/003 Stara Zagora - Dimitrovgrad: construction of new wastewater treatment plants 43.399.688 32.549.766 2001/BG/16/P/PE/005 Gorna: wastewater collection and treatment 16.633.945 12.475.459 2001/BG/16/P/PE/006 Pazardjik wastewater collection and treatment 19.110.968 12.422.129 2001/BG/16/P/PE/008 Blagoevgrad wastewater treatment plant 12.580.465 8.806.326 2002/BG/16/P/PE/009 Bourgas-Meden Rudnik wastewater collection and treatment 10.206.220 7.654.665 2002/BG/16/P/PE/010 Targovishte wastewater collection and treatment 15.235.915 11.426.936 2002/BG/16/P/PE/011 Lovech wastewater collection and treatment 18.396.575 13.797.431 2002/BG/16/P/PE/012 Montana wastewater collection and treatment 16.741.237 12.555.928 2002/BG/16/P/PE/013 Smoljan Integrated water project 24.471.021 18.353.266 2002/BG/16/P/PE/014 Sevlievo wastewater collection and treatment 13.987.623 10.490.717 2002/BG/16/P/PE/015 Popovo wastewater collection and treatment 11.860.433 8.895.326 2002/BG/16/P/PE/016 Varna integrated water project 25.432.000 19.074.000 2002/BG/16/P/PE/017 Balchik: Integrated water project 21.589.225 16.191.919 2002/BG/16/P/PE/018 Shumen: water cycle improvements 30.130.000 22.597.500 2003/BG/16/P/PE/019 Kardjali: -

Preliminary Report on an Ongoing Outbreak of Hepatitis a in Estonia, 2011

Rapid communications Preliminary report on an ongoing outbreak of hepatitis A in Estonia, 2011 I Dontšenko ([email protected])1, N Kerbo1, J Pullmann2, S Plank3, N Võželevskaja4, K Kutsar1 1. Health Board, Tallinn, Estonia 2. Southern Service of the Health Board, Viljandi, Estonia 3. Southern Service of the Health Board, Tartu, Estonia 4. Northern Service of the Health Board, Tallinn, Estonia Citation style for this article: Dontšenko I, Kerbo N, Pullmann J, Plank S, Võželevskaja N, Kutsar K. Preliminary report on an ongoing outbreak of hepatitis A in Estonia, 2011. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(42):pii=19996. Available online: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19996 Article published on 20 October 2011 Since the beginning of August 2011, an outbreak of from another county, who had visited Viljandi city or hepatitis A has been detected in Estonia. The major- had had contact with a Viljandi county resident from 4 ity of laboratory-confirmed cases (n=66) were notified June 2011 onwards. between 4 August and 3 October 2011 and were linked to Viljandi county. The outbreak is still ongoing. Between 4 August and 3 October 2011, 66 confirmed cases of hepatitis A, linked to Viljandi county were Outbreak description notified. This constituted the majority of 71 cases of Since the beginning of August 2011, an increase in the hepatitis A notified during the same period in Estonia, number of hepatitis A notifications has been observed the highest number of cases (n=51) was notified in in Estonia. The majority of cases were notified in September. Viljandi county or epidemiologically linked to Viljandi county. -

On the Development of the Town of Viljandi in the Light of Earliest Archaeological Find Complexes

Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 2013, 17, 1, 57–86 doi: 10.3176/arch.2013.1.04 Arvi Haak and Erki Russow ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE TOWN OF VILJANDI IN THE LIGHT OF EARLIEST ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIND COMPLEXES Numerous attempts have been made to reconstruct the development of the medieval town of Viljandi (south Estonia), yet the source material is extremely scarce. The current article reviews the existing written sources and reconstruction maps, and introduces to provide an introduction of the existing archaeological sources, on the basis of context-related analysis of finds from the earliest deposits all over the territory of the medieval town, with special attention on pottery as the most numerous find type. On this basis, a new development scheme of Viljandi, based on the dating of the find complexes, is suggested and the concept of Paul Johansen of Viljandi as a typical “founded” town is examined. The authors reach the conclusion that all strata with 13th-century finds (with the exception of the complex of a pottery kiln in Pikk Street) were located in the northern part of the town, and a spatial connection between the castle and the emerging town is not as striking as has been stated earlier. The diversity of pottery imports, on the other hand, increased from the end of the 13th century. Arvi Haak, Institute of History, Tallinn University, 6 Rüütli St., 10130 Tallinn / Tartu City Museum, 23 Narva Road, 51009 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] Erki Russow, Institute of History, Tallinn University, 6 Rüütli St., 10130 Tallinn, Estonia; [email protected] Introduction Among the nine medieval towns in the territory of the present-day Estonia, Viljandi was one of the four members of the Hanseatic League.