Dvorák Day Concert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gershwin, from Broadway to the Concert Hall SONGS

Gershwin, from Broadway to the Concert Hall americaSONGS | RHAPSODY IN BLUE | CONCERTO IN F | SUMMERTIME . ! Volume 1 Volume 2 GEORGE GERSHWIN (1898-1937) ORCHESTRAL MUSIC PIANO SOLO 1 “I Got Rhythm” Variations for Piano and Orchestra (1934) 8’29 Original orchestration by George Gershwin Song Book (18 hit songs arranged by the composer) 2 4’05 1 The Man I Love. Slow and in singing style 2’25 Summertime George Gershwin, DuBose Heyward. From Porgy and Bess, 1935 2 I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise. Vigorously 0’44 3 ‘s Wonderful. Liltingly 1’00 3 Rhapsody in Blue (1924) 15’31 4 I Got Rhythm. Very marked 1’05 Original ‘jazz band’ version 5 Do It Again. Plaintively 1’38 © Warner Bros. Music Corporation 6 Clap Yo’Hands. Spirited (but sustained) 0’56 Lincoln Mayorga, piano (1-3) 7 Oh, Lady Be Good. Rather slow (with humour) 1’04 8 Fascinating Rhythm. With agitation 0’51 Harmonie Ensemble / New York, Steven Richman 9 Somebody Loves Me. In a moderate tempo 1’17 10 My One and Only. Lively (in strong rhythm) 0’51 11 That Certain Feeling. Ardently 1’36 Piano Concerto in F 12 Swanee. Spirited 0’38 4 I. Allegro 13’18 13 Sweet and Low Down. Slow (in a jazzy manner) 1’05 5 II. Adagio 12’32 14 Nobody But You. Capriciously 0’53 6 III. Allegro agitato 6’48 15 Strike Up the Band. In spirited march tempo 0’56 7 Cuban Overture 10’36 16 Who Cares? Rather slow 1’30 © WB Music Corp. -

A Successful Season--So Far a P a PLACE for JAZZ O R

A P A PLACE FOR JAZZ O R J Website: http://www.timesunion.com/communities/jazz/—Updated daily A Successful Season--so far by Tim Coakley The 2005 season is rolling Dan Levinson and his along, and so far the con- Summa cum Laude Or- certs have been as suc- chestra re-created some cessful as they have been Bud Freeman Chicago- Inside this issue: varied. In addition, we style classics with verve attracted reviewers from and precision. Dan played Metroland and the Times both clarinet and sax, and M and M’s 3 Union, as well as The Daily Randy Reinhart led the Gazette. Here's a brief run- way with some sparkling down of the series to date: Calendar 4-5 cornet. Features 9 & 11 Dynamic pianist Hilton Ruiz and his Quintet pro- vided a mixture of Latin Jazz Times 6-7 music and bebop that got some members of the audi- Who IS this youthful drum- ence mer? (see page 3 for his dancing. Drummer Sylvia identity) Cuenca captured every- one's attention with her percussionistic pyrotech- nics. John Bailey & Gregg August VOLUNTEER HELP with kids at HHAC WANTED Hilton also worked with (photo by Jody Shayne) student musicians at SCCC, and showed We need help: Hamilton Hill youngsters Labeling newsletters (1 hour every how different styles of jazz 3 months…can be done at home) Bassist Gregg August and his sextet challenged us piano sounded. Musician John Bailey shows his Writing music reviews horn to young people at HHAC with some original and pro- Working on a young people’s (photo by Jody Shayne) project at the Hamilton Hill Art vocative compositions, At press time, we were get- Center along with fiery solos by ting ready to enjoy the vo- Check out our update monthly saxophonists Myron Wal- cal stylings of Roseanna calendar. -

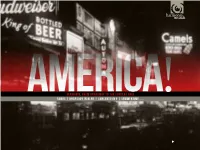

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic “When Johnny Cash comes on the radio, no one changes the station. It’s a voice, a name with a soul that cuts across all boundaries and it’s a voice we all believe. Yours is a voice that speaks for the saints and the sinners – it’s like branch water for the soul. Long may you sing out. Loud.” – Tom Waits audio int‘l p. o. box 560 229 60407 frankfurt/m. germany www.audio-intl.com Catalog: IMP 6008 Format: 180-gram LP tel: 49-69-503570 mobile: 49-170-8565465 Available Spring 2011 fax: 49-69-504733 To order/preorder, please contact your favorite audiophile dealer. Jennifer Warnes, Famous Blue Raincoat. Shout-Cisco (three 200g 45rpm LPs). Joan Baez, In Concert. Vanguard-Cisco (180g LP). The 20th Anniversary reissue of Warnes’ stunning Now-iconic performances, recorded live at college renditions from the songbook of Leonard Cohen. concerts throughout 1961-62. The Cisco 45 rpm LPs define the state of the art in vinyl playback. Holly Cole, Temptation. Classic Records (LP). The distinctive Canadian songstress and her loyal Jennifer Warnes, The Hunter. combo in smoky, jazz-fired takes on the songs of Private-Cisco (200g LP). Tom Waits. Warnes’ post-Famous Blue Raincoat release that also showcases her own vivid songwriting talents in an Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Déjá Vu. exquisite performance and recording. Atlantic-Classic (200g LP). A classic: Great songs, great performances, Doc Watson, Home Again. Vanguard-Cisco great sound. The best country guitar-picker of his day plays folk ballads, bluegrass, and gospel classics. -

The Playlist!

THE SOUNDS OF THE SEASON NOON, DECEMBER 24 - MIDNIGHT, DECEMBER 25, 2020 PRESENTED BY JAZZ 88.3 KSDS Number Name Artist Album Time Hour #01 NOON TO 1 PM DECEMBER 24 001 The Sounds of the Season - Open 0:45 002 ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas Chuck Niles 3:46 003 Jingle Bells Duke Ellington Jingle Bell Jazz (rec. 1962) 3:02 004 Frosty the Snowman Roy Hargrove & Christian McBride Jazz for Joy - A Verve Christmas Album (rec. 1996) 3:56 005 Sleigh Ride Ella Fitzgerald Ella Wishes You a Swinging Christmas! (rec. 1960) 2:59 006 Winter Wonderland The Ramsey Lewis Trio Sound of Christmas (rec. 1961) 2:08 007 O Tannenbaum Vince Guaraldi A Charlie Brown Christmas (rec. 1964) 5:09 008 Home for the Holidays Joe Pass Six-String Santa (rec. 1992) 4:00 009 The Sounds of the Season ID 0:45 010 Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Brynn Stanley Classic Christmas (rec. 2019) 3:44 011 Line for Santa Octobop West Coast Christmas (rec. 2012 4:07 012 White Christmas Booker Ervin Structurally Sound (rec. 1966) 4:28 013 Deck the Halls Gerry Beaudoin & The Boston Jazz Ensemble A Sentimental Christmas (rec. 1994) 2:39 014 I’ll Be Home for Christmas Tony Bennett The Tony Bennett Christmas Album 2:14 015 The Christmas Song Scott Hamilton Christmas Love Song (rec. 1997) 5:44 016 Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas Ron Affif Christmas Songs (rec. 1992) 5:01 017 The Christmas Waltz Beegie Adair Trio Jazz Piano Christmas (rec. 1989) 2:42 HOUR #02 1 PM TO 2 PM DECEMBER 24 018 The Sounds of the Season ID 0:45 019 A Holly Jolly Christmas Straight No Chaser Social Christmasing (rel. -

Honors Concerts 2015

Honors Concerts 2015 Presented By The St. Louis Suburban Music Educators Association and Education Plus St. Louis Suburban Music Educators Association Affiliated With Education Plus Missouri Music Educators Association MENC - The National Association for Music Education www.slsmea.com EXECUTIVE BOARD – 2014-16 President 6th Grade Orchestra VP Jason Harris, Maplewood-Richmond Heights Twinda, Murry, Ladue President-Elect MS Vocal VP Aaron Lehde, Ladue Lora Pemberton, Rockwood Valerie Waterman, Rockwood Secretary/Treasurer James Waechter, Ladue HS Jazz VP Denny McFarland, Pattonville HS Band VP Vance Brakefield, Mehlville MS Jazz VP Michael Steep, Parkway HS Orchestra VP Michael Blackwood, Rockwood Elementary Vocal Katy Frasher, Orchard Farm HS Vocal VP Tim Arnold, Hazelwood MS Large Ensemble/Solo Ensemble Festival Director MS Band VP David Meador, St. Louis Adam Hall, Pattonville MS Orchestra VP Tiffany Morris-Simon, Hazelwood Order a recording of today’s concert in the lobby of the auditorium or Online at www.shhhaudioproductions.com St. Louis Suburban 7th and 8th Grade Treble Honor Choir Emily Edgington Andrews, Conductor John Gross, Accompanist January 10, 2015 Rockwood Summit High School 3:00 P.M. PROGRAM Metsa Telegramm …………………………………………………. Uno Naissoo She Sings ………………………………………………………….. Amy Bernon O, Colored Earth ………………………………………………….. Steve Heitzig Dream Keeper ………………………………………………….. Andrea Ramsey Stand Together …………………………………………………….. Jim Papoulis A BOUT T HE C ONDUCTOR An advocate for quality musical arts in the community, Emily Edgington Andrews is extremely active in Columbia, working with children and adults at every level of their musical development. She is the Fine Arts Department Chair and vocal music teacher at Columbia Independent School, a college preparatory campus. Passionate about exposing students to quality choral music education, she has received recognition for her work in the classroom over the years, most recently having been awarded the Charles J. -

Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf194 No online items Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043 Finding aid prepared by Frank Ferko and Anna Hunt Graves This collection has been processed under the auspices of the Council on Library and Information Resources with generous financial support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Archive of Recorded Sound Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford University Stanford, California, 94305-3076 650-723-9312 [email protected] 2011 Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium ARS.0043 1 Collection ARS.0043 Title: Ambassador Auditorium Collection Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0043 Repository: Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California 94305-3076 Physical Description: 636containers of various sizes with multiple types of print materials, photographic materials, audio and video materials, realia, posters and original art work (682.05 linear feet). Date (inclusive): 1974-1995 Abstract: The Ambassador Auditorium Collection contains the files of the various organizational departments of the Ambassador Auditorium as well as audio and video recordings. The materials cover the entire time period of April 1974 through May 1995 when the Ambassador Auditorium was fully operational as an internationally recognized concert venue. The materials in this collection cover all aspects of concert production and presentation, including documentation of the concert artists and repertoire as well as many business documents, advertising, promotion and marketing files, correspondence, inter-office memos and negotiations with booking agents. The materials are widely varied and include concert program booklets, audio and video recordings, concert season planning materials, artist publicity materials, individual event files, posters, photographs, scrapbooks and original artwork used for publicity. -

GERSHWIN by GROFÉ Symphonic Jazz Original Orchestrations & Grofé/Whiteman Orchestra Arrangements

NB: Since the cd booklet program notes are abridged, we have provided the complete notes with more detailed information below: GERSHWIN by GROFÉ Symphonic Jazz Original Orchestrations & Grofé/Whiteman Orchestra Arrangements STEVEN RICHMAN, conductor Lincoln Mayorga, piano Al Gallodoro, alto sax, clarinet, bass clarinet Harmonie Ensemble/New York Harmonia Mundi CD 907492 Program Notes During the 1920s, there existed a symbiotic relationship between George Gershwin, Paul Whiteman, and Ferde Grofé that was both fascinating and fruitful. This remarkable trio had had some association during the 1922 edition of the George White Scandals, for which Gershwin composed the score, with lyrics by Buddy DeSylva and, in the case of the hit song, “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise,” George’s brother Ira as well (as Arthur Francis). But their only other collaboration, and the one upon which a significant chapter of American music turned, occurred during the creation of the Rhapsody in Blue for the historic concert at Aeolian Hall in New York City on February 12, 1924, which Whiteman called “An Experiment in Modern American Music.” Each of the three made a significant contribution to the birthing of this landmark piece which epitomized, and indeed was the arguably the finest example of, the genre of music known as “symphonic jazz.” For nearly ten years, Whiteman, who had been classically trained, and formerly a violinist in the San Francisco Symphony, had contemplated the amalgamation of classical music and jazz. Beginning with the organization of his hotel bands in California in 1918, he began to experiment with this concept, which he termed “symphonic jazz.” By the fall of 1920 he had come east, and the nine-piece band that he had assembled quickly took New York by storm. -

Steinway Artists On

Steinway Artists on David Benoit – Jazz pianist, composer, conductor and a five-time Grammy nominee Jon Kimura Parker – A keyboard wizard who is equally at home playing jazz or the classics Ruth Laredo – First Lady of American piano and a highly esteemed Grammy nominee Grant Johannesen – Much honored keyboard master and a champion of French music Peter Nero – This Grammy-winning pianist, composer and conductor has scores of #1 hits and Gold Records to his credit Andre-Michel Schub – The winner of 1974 Naumberg, 1977 Avery Fisher & 1981 Cliburn Richard Glazier – A leading authority on American Popular Song, star of two PBS specials Larry Dalton – An award winning and highly regarded sacred musician, conductor and arranger who played all over the world John Bayless – A musical genius who plays Beatles songs in the style of Bach and combines pop and classical music Beegie Adair – A terrific jazz pianist who makes fans whenever and wherever she plays Barry Douglas - Celebrated winner of the Earl Rose – Popular pianist and Emmy-winning Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition, composer for television and movies this Irish pianist plays all over the world Lincoln Mayorga – Versatility is the word for this great pianist who plays classical, jazz and pop with equally facility Alicia Zizzo – Pianist and musicologist, Ms. Zizzo made history with her reconstructed version of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue Andreas Klein – Esteemed pianist and educator, Klein is admired for his insightful interpretations Laura Spitzer – Ms. Spitzer is famous as a true “traveling musician” who loaded her Steinway on a truck and brought great music to rural areas Butch Thompson – Mr. -

What It Takes to Be a Successful Concert Artist: Conversations with World Renowned Musicians by Rebecca Jackson

What it Takes to be a Successful Concert Artist: Conversations with World Renowned Musicians By Rebecca Jackson Introduction How does one become a successful concert artist? During my twenty one years of studying and performing as a violinist I continue to witness many like myself spend tireless hours trying to master the great works. Besides the obvious requirement of work on your craft I have always been curious of other factors present in the journey musicians take to establish their success. Why become a classical musician in the first place? Odds don't seem to be stacked in our favor. At first glance, what you see on stage may seem glamorous. Hundreds of people flock to watch and listen to beautiful music performed effortlessly. Paganini, Liszt, Heifetz, and Horowitz are some of the legendary performers that come to mind. Despite the initial attraction, the life of a musician is strewn with difficulties and unpredictabilities. Leila Josefowicz said, “The lifestyle of this whole business is awful. I'll not mince words about that.”1 The unattractive aspects I have observed create a substantial list: (1) It is a life led in solitude within the four walls of a practice room. While I was studying at Juilliard the average daily practice session was between five and eight hours. And this is a ritual that begins very early in life. (2) Musicians spend equal if not more time studying than doctors and yet “starving artist” depicts the characteristically little money we earn. (3) One endures constant scrutiny. Even the note-perfect Heifetz made Dallas front-page news, “HEIFETZ FORGETS,” when music came to a stop during the Sibelius Violin Concerto.2 (4) Perfectionism is a common trait making it rare to feel completely satisfied with one's performance. -

Sounds of the Season 6 Am December 24 - 8 Pm December 25, 2016 Jazz 88.3 Ksds

SOUNDS OF THE SEASON 6 AM DECEMBER 24 - 8 PM DECEMBER 25, 2016 JAZZ 88.3 KSDS Number Name Artist Album Time Hour #1 6 AM to 7 AM December 24 001 SOS 2105 KSDS Open 0:45 002 ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas Chuck Niles 3:46 003 Sleigh Ride Richie Cole Mistletoe Magic: Holiday Jazz Impressions 5:50 004 Jingle Bells Duke Ellington Jingle Bell Jazz 3:02 005 The Twelve Days of Christmas Stan Kenton Orchestra A Merry Christmas 4:08 006 Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas Ella Fitzgerald Ellas Wishes You a Swinging Christmas 2:58 007 S.C. Is Coming to Town Martin Mann & Mannkind Christmastime 4:41 008 Silver Bells Oliver Jones Yuletide Swing 5:07 009 SOS 2105 KSDS BOH ID #1 0:36 010 The Christmas Song Carmen McRae Jingle Bell Jazz 3:58 011 Do You Hear What I Hear? Jimmy Ponder Guitar Christmas 4:54 012 Christmas Is Coming Vince Guaraldi A Charlie Brown Christmas 3:28 013 A Christmas Medley Mel Tormé Christmas Songs 4:17 014 Winter Wonderland Oscar Peterson An Oscar Peterson Christmas 4:11 015 God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen Kenny Burrell Have Yourself a Soulful Little Christmas 3:48 016 I’ve Got My Love to Keep Me Warm Julie London Ultra-Lounge Christmas Cocktails, Pt. 3 4:14 017 The Sound of Christmas The Ramsey Lewis Trio Sound of Christmas 2:21 Hour #2 7 AM to 8 AM December 24 018 SOS 2105 KSDS TOH ID #2 0:34 019 Baby, It’s Cold Outside Leon Redbone & Zoey Deschanel Elf Soundtrack 3:32 020 Santa Claus Came in the Spring Sackville All-Stars The Sackville All-Star Christmas Record 5:16 021 Jingle Bells Swing Jim Cullum Jazz Band Hot Jazz for a Cool Yule 2:22 022 Christmas Carnival David Hickman, Thomas Bacon, Sam Palafian A Cool Brassy Night at the North Pole 3:28 023 Manhattan in December Ann Hampton Calloway Wonderland - Under the Mistletoe 3:43 024 Christmas Waltz Scott Hamilton Chritsmas Love Song 5:17 025 Santa Claus Is Coming to Town Joshua Redman and Brad Mehldau Warner Bros. -

Pianodisc Music Catalog.Pdf

Welcome Welcome to the latest edition of PianoDisc's Music Catalog. Inside you’ll find thousands of songs in every genre of music. Not only is PianoDisc the leading manufacturer of piano player sys- tems, but our collection of music software is unrivaled in the indus- try. The highlight of our library is the Artist Series, an outstanding collection of music performed by the some of the world's finest pianists. You’ll find recordings by Peter Nero, Floyd Cramer, Steve Allen and dozens of Grammy and Emmy winners, Billboard Top Ten artists and the winners of major international piano competi- tions. Since we're constantly adding new music to our library, the most up-to-date listing of available music is on our website, on the Emusic pages, at www.PianoDisc.com. There you can see each indi- vidual disc with complete song listings and artist biographies (when applicable) and also purchase discs online. You can also order by calling 800-566-DISC. For those who are new to PianoDisc, below is a brief explana- tion of the terms you will find in the catalog: PD/CD/OP: There are three PianoDisc software formats: PD represents the 3.5" floppy disk format; CD represents PianoDisc's specially-formatted CDs; OP represents data disks for the Opus system only. MusiConnect: A Windows software utility that allows Opus7 downloadable music to be burned to CD via iTunes. Acoustic: These are piano-only recordings. Live/Orchestrated: These CD recordings feature live accom- paniment by everything from vocals or a single instrument to a full-symphony orchestra. -

Newsletter August 06.Pub

A P A PLACE FOR JAZZ O R August 2006 Editor: Tim Coakley WEBSITE: HTTP://WWW.APLACEFORJAZZ.ORG—UPDATED DAILY Here Comes the Fall Season By Tim Coakley A Place for bers and offi- Web Site News VOLUNTEER HELP Jazz is ready cers will be WANTED to go with an- posted on our other season On our own Web site There's a new way to reach our web site! The We need help: of top-quality soon: jazz for your www.aplacefo old URL Labeling newsletters (1 hour listening en- In other news, rjazz.org. (www.timesunion.com/com every 3 months…can be done in the process munities/jazz) will still at home) joyment. We of continuing We will still work, so if you've already will kick off our got it in your Favorites, you Writing music reviews the tradition rely on our 2006 season board mem- don't have to do anything. Working on a young people’s Friday, Sept. established by But otherwise, you can project at the Hamilton Hill Butch Conn, bers and vol- 15 with the unteers to out- now get to our web site Art Center our late foun- with Winard Harper line and carry Sextet. This der, A Place www.aplaceforjazz.org. out the many Much simpler and more If you can help, please call top-notch for Jazz is in tasks and du- professional, don't you Tim Coakley at drummer and the process of establishing ties that go think? 518-393-4011 his group with present- have been itself as a non- or e-mail him at profit entity, ing a concert appearing at series like [email protected] festivals and with a board of directors ours.