Chapter 2 Major Findings of External School Reviews (ESR)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T It W1~~;T~Ril~T,~

University of Hong Kong Libraries Publications, No.7 LIBRARIES AND INFORMATION CENTRES IN HONG KONG t it W1~~;t~RIl~t,~ Compiled and edited by Julia L.Y. Chan ~B~ B.A., M.L.S., A.H.I.P., FHKLA Angela S.W. Van I[I~Uw~ B.A., M.L.S., A.H.I.P., A.A.L.I.A. Kan Lai-bing MBiJl( B.Sc., M.A., M.L.S., Ph.D., Hon. D.Litt, A.L.A.A., M.I.Inf. Sc., FHKLA Published for The Hong Kong Library Association by Hong Kong University Press * 1~ *- If ~ )i[ ltd: Hong Kong University Press 139 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong © Hong Kong University Press 1996 ISBN 962 209 409 0 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in Hong Kong by United League Graphic & Printing Company Limited Contents Plates Preface xv Introduction xvii Abbreviations & Acronyms xix Alphabetical Directory xxi Organization Listings, by Library Types 533 Libraries Open to the Public 535 Post-Secondary College and University Libraries 538 School Libraries 539 Government Departmental Libraries 550 HospitallMedicallNursing Libraries 551 Special Libraries 551 Club/Society Libraries 554 List of Plates University of Hong Kong Main Library wnt**II:;:tFL~@~g University of Hong Kong Main Library - Electronic Infonnation Centre wnt**II:;:ffr~+~~n9=t{., University of Hong Kong Libraries - Chinese Rare Book Room wnt**II:;:i139=t)(~:zjs:.~ University of Hong Kong Libraries - Education -

港島及長洲hong Kong Island and Cheung Chau

港島及長洲 Hong Kong Island and Cheung Chau 學校編號 學校名稱 學校地址 准予報考的香港中學文憑 School School Name School Address 實驗科目 Code Approved HKDSE Practical Subjects 10001 香港仔浸信會呂明才書 香港鴨脷洲 利東邨道 18 Bio Chem Phy 院 號 Sci (Com) Bio Aberdeen Baptist Lui 18 Lei Tung Estate Road, Sci (Com) Chem Ming Choi College Apleichau, Hong Kong. Sci (Com) Phy 10002 香港仔工業學校 香港香港仔 黃竹坑道 1 號 Bio Chem Phy Sci (Int) Aberdeen Technical 1 Wong Chuk Hang Road, Sci (Com) Bio School Aberdeen, Hong Kong. Sci (Com) Chem Sci (Com) Phy DAT 10003 遵理學校(銅鑼灣) 香港銅鑼灣謝斐道 482 號 Beacon College 信諾環球保險中心 3 樓 香 (Causeway Bay) 港銅鑼灣高士威道 16-22 號 高威樓 2 樓 3/F Cigna Tower, 482 Jaffe Road, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2/F Causeway Tower, 16-22 Causeway Road, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 10004 庇理羅士女子中學 香港北角 天后廟道 51 號 Bio Chem Phy Belilios Public School 51 Tin Hau Temple Road, Sci (Com) Bio North Point, Hong Kong. Sci (Com) Chem Sci (Com) Phy 10005 達海書院 香港北角 渣華道 210 號 2 Betterment College 樓 2/F, 210 Java Road, North Point, Hong Kong. 10006 佛教慧因法師紀念中學 香港長洲 大興堤路 25 號 Bio Chem Phy Buddhist Wai Yan 25 Tai Hing Tai Road, Memorial College Cheung Chau, Hong Kong. 10007 佛教黃鳳翎中學 香港銅鑼灣 東院道 11 號 Bio Chem Phy Buddhist Wong Fung Ling 11 Eastern Hospital Road, College Causeway Bay, Hong Kong. Schools that have not presented students for the 2018 HKDSE are shown in grey. 未有保送學生參加 2018 年香港中學文憑考試的學校以灰色字體標示。 學校編號 學校名稱 學校地址 准予報考的香港中學文憑 School School Name School Address 實驗科目 Code Approved HKDSE Practical Subjects 10008 嘉諾撒書院 香港鰂魚涌 海澤街 10 號 Bio Chem Phy Canossa College 10 Hoi Chak Street, Quarry Sci (Com) Bio Bay, Hong Kong. -

Basketball 1718

Basketball Hong Kong Island Division 1 Boys Girls School Abbr. ABAB 1 Belilios Public School BPS 1 1 2 CCC Kwei Wah Shan College KWSC 1 1 Division 2 3 Cheung Chuk Shan College CCSCDivision 3 1 1 4 Chong Gene Hang College CGHC 1 1 5 German Swiss International School GSISDivision 2 1 1 6 HKUGA College HKUGADivision 2 1 1 7 Hon Wah College HW 1111 8 King's College KC 1 1 9 Precious Blood Secondary School PBSS 1 1 10 Queen's College QC 1 1 11 Raimondi College RC 1 1 12 Sacred Heart Canossian College SHCC 1 1 13 Salesian English School (Secondary Section) SS 1 1 14 St. Paul's Co-Educational College SPCC 1111 15 St. Paul's College SPC 1 1 16 St. Stephen's College SSCS 1 1 Division 2 17 St. Stephen's Girls' College SSGC 1 1 18 The South Island School TSIS 1111 19 True Light Middle School of Hong Kong TLMSHK 1 1 20 Wah Yan College (Hong Kong) WYHK 1 1 21 Ying Wa Girls' School YWG 1 1 Total: 12 12 12 12 Basketball Hong Kong Island Division 2 Boys Girls School Abbr. ABAB 1 Aberdeen Baptist Lui Ming Choi College ABLMCC 1111 2 Buddhist Wong Fung Ling College BWFLDivision 3 1 1 3 Canossa College CC 1 1 4 Caritas Chaiwan Marden Foundation Secondary School CCMFSSDivision 3 1 5 CCC Kwei Wah Shan College KWSCDivision 1 1 6 Cognitio College (Hong Kong) CCHKDivision 3 1 1 7 Delia School of Canada (Secondary Division) DSCDivision 3 1 8 French International School FISDivision 3 1 9 Fukien Secondary School (Siu Sai Wan) FSS-SSW 1111 10 German Swiss International School GSIS 1 1 Division 1 11 Henrietta Secondary School HSDivision 3 1 12 HKUGA College HKUGA 1 1 Division 1 13 Hong Kong Chinese Women's Club College CWCCDivision 3 1 1 14 Hong Kong True Light College HKTLC 1 1 15 Hotung Secondary School HSS 1 1 16 Lingnan Secondary School LNSS 1 1 17 Marymount Secondary School MSS 1 1 18 Munsang College (Hong Kong Island) MSCHK 1 1 19 Pui Tak Canossian College PTCC 1 20 Rosaryhill School RS 1111 21 Shaukeiwan Government Secondary School SKWGSS 1 1 22 SKH Lui Ming Choi Secondary School SKHLMCDivision 3 1 1 23 SKH Tang Shiu Kin Secondary School SKHTSK 1111 24 St. -

Champion Schools.Xlsx

The Hong Kong Schools Sports Federation HK Island & Kowloon Secondary Schools Regional Committee List of Champion Schools 2008-2009 Sport Area Division Type Grade School Athletics - One - Boys A Diocesan Boys' School Boys B La Salle College Boys C Diocesan Boys' School Boys Overall Diocesan Boys' School Girls A Diocesan Girls' School Girls B Diocesan Girls' School Girls C Diocesan Girls' School Girls Overall Diocesan Girls' School - Two - Boys A Ng Wah Catholic Secondary School Boys B Buddhist Hung Sean Chau Memorial College Boys C St. Margaret's Co-educational English Secondary and Primary School Boys Overall Ng Wah Catholic Secondary School Girls A Hoi Ping Chamber of Commerce Secondary School Girls B Hong Kong True Light College Girls C Pui Ching Middle School Girls Overall Pui Ching Middle School A1 Three - Boys A Delia Memorial School - Hip Wo Boys B CCC Heep Woh College Boys C STFA Cheng Yu Tung Secondary School Boys Overall STFA Cheng Yu Tung Secondary School Girls A Carmel Divine Grace Foundation Secondary School Girls B Our Lady of The Rosary College Girls C Our Lady of The Rosary College Girls Overall Our Lady's College A2 Three - Boys A Pentecostal School Boys B Queen's College Boys C St. Francis Xavier's College Boys Overall Queen's College Girls A Kit Sam Lam Bing Yim Secondary School Girls B Kit Sam Lam Bing Yim Secondary School Girls C Buddhist Hung Sean Chau Memorial College Girls Overall Kit Sam Lam Bing Yim Secondary School A3 Three - Boys A Tsung Tsin Middle School Boys B Salesian English School - Secondary Section Boys C St. -

Annual Report of the Provisional Legislative Council

C O N T E N T S PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD GROUP PHOTO OF MEMBERS MAJOR EVENTS IN PICTURES CHAPTER 1 The Provisional Legislative Council CHAPTER 2 Provisional Legislative Council Meetings Tabling of Subsidiary Legislation and Other Papers Questions Statements Bills Motions and Debates Policy Address Debate Budget Debate Chief Executive’s Question and Answer Sessions CHAPTER 3 Committees Finance Committee Public Accounts Committee Committee on Members’ Interests House Committee - Subcommittees of the House Committee Committee on Rules of Procedures Bills Committees and Subcommittees Panels CHAPTER 4 Redress System Analysis of Significant Cases Dealt With - 1 - CHAPTER 5 Liaison Liaison with Shenzhen Municipal Government Overseas Visits by Members Lunch with Consuls General Contact with Provisional Municipal Councils and Provisional District Boards Visitors CHAPTER 6 Support Services for Members The Provisional Legislative Council Commission The Provisional Legislative Council Secretariat - 2 - A P P E N D I C E S APPENDIX 1 Members’ Biographies APPENDIX 2 Bills Passed APPENDIX 3 Motion Debates Held APPENDIX 4 Membership of Committees, Panels, Bills Committees and Subcommittees APPENDIX 5 Redress Information System: Nature and Outcome of Cases Completed Between 1 July 1997 and 30 June 1998 APPENDIX 6 Redress Information System: Statistics Report Between 1 July 1997 and 30 June 1998 APPENDIX 7 Visitors APPENDIX 8 Membership of The Provisional Legislative Council Commission and its Committees APPENDIX 9 Organization of the Provisional Legislative Council Secretariat - 3 - P R E S I D E N T ’ S F O R E W O R D The establishment of the Provisional Legislative Council in December 1996 was a major step towards the smooth transition of Hong Kong’s reunification with China. -

2016-2017 年報 3 執行委員會主席的話 Message from the Chairperson of the Executive Committee

AnnualReport_1617_cover.pdf 1 18/10/2017 下午5:35 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 宗旨 你錨可穩歌 Objective Will Your Anchor Hold 於青少年人之間,擴展基督的國度,同時促進服 從、虔誠、紀律及自愛等良好行為,以達成基督化 1. 雲端起強風展開威武力,洶湧巨浪牽張你錨鍊, 的人格。 你錨仍穩靠或已被拔起,處身人生波濤錨可穩。 2. 浪吼澎湃聲已近危礁石,野風吹過大浪又翻騰, The advancement of Christ’s Kingdom among 怒海發狂濤向船首捲掃,你在恐懼峽流錨可穩。 young people and the promotion of habits of 3. 在晨曦之中你可曾眼見,光明海港黃金城在望, Obedience, Reverence, Discipline, Self-respect and 經生命風濤始能達彼岸,天國之濱你錨得穩靠。 all that tends towards a true Christian Manliness. 副歌: 格言 我等靈魂有錨來保守,靠著不變磐石作錨地, 是堅固牢靠足禦風浪,藏身救主愛懷內真安穩。 Motto Will your anchor hold in the storms of life, 我們有這指望,如同靈魂的錨,又堅固、又牢靠。 (希伯來書 6:19) When the clouds unfold their wings of strife? When the strong tides lift, and the cables strain, We have this as a sure and stedfast anchor of the soul, a hope that enters into the inner shrine behind Will your anchor drift, or firm remain? the curtains. (Hebrews 6:19) We have an anchor that keeps the soul, Stedfast and sure while the billows roll, Fasten’d to the rock which cannot move, 會徽 Grounded firm and deep in the Saviour’s love! Emblem 會徽主要是個錨,表達:「我們有這指望,如同靈 魂的錨」的意思。 Our emblem is in the shape of an anchor, expressing the meaning of our Motto: “We have this as a sure and stedfast anchor of the soul.” Annual Report 2015-2016 年報 61 目 Contents 錄 2-3 機構簡介 43 香港基督少年軍之友報告 About Us Report from Stedfast Association, Hong Kong 4-5 執行委員會主席的話 44-45 職員培訓及團隊活動 Message from the Chairperson of the Executive Committee Staff Development and Team-Building Activities 6-7 總幹事報告 46 中央行政及管理 Report from the General Secretary Central Administration -

List of Champion Schools 2010-2011

The Hong Kong Schools Sports Federation HK Island & Kowloon Secondary Schools Regional Committee List of Champion Schools 2010-2011 Sport Area Division Type Grade School Archery - - - Boys A La Salle College Boys B La Salle College Boys C Diocesan Boys' School Boys Overall La Salle College Girls A STFA Seaward Woo College Girls B STFA Seaward Woo College Girls C STFA Seaward Woo College Girls Overall STFA Seaward Woo College Athletics - One - Boys A La Salle College Boys B La Salle College Boys C Diocesan Boys' School Boys Overall La Salle College Girls A Diocesan Girls' School Girls B Diocesan Girls' School Girls C Good Hope School Girls Overall Diocesan Girls' School - Two - Boys A Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui Bishop Hall Secondary School Boys B Chan Sui Ki (La Salle) College Boys C Ying Wa College Boys Overall STFA Cheng Yu Tung Secondary School Girls A Pui Ching Middle School Girls B Pui Ching Middle School Girls C Hong Kong True Light College Girls Overall Pui Ching Middle School A1 Three - Boys A New Asia Middle School Boys B Chinese International School Boys C Sing Yin Secondary School Boys Overall Sing Yin Secondary School Girls A Our Lady of The Rosary College Girls B YCH Law Chan Chor Si College Girls C Christian & Missionary Alliance Sun Kei Secondary School Girls Overall Our Lady of The Rosary College A2 Three - Boys A New Method College Boys B St. Francis Xavier's College Boys C Tseung Kwan O Government Secondary School Boys Overall St. Francis Xavier's College Girls A Heung To Middle School (Tai Hang Tung) Girls B Evangel College Girls C Po Leung Kuk Ngan Po Ling College Girls Overall Evangel College A3 Three - Boys A TWGHs Chang Ming Thien College Boys B TWGHs Chang Ming Thien College Boys C G. -

Secondary School Places Allocation System Seminar 20-4-2018 Secondary School Places Allocation (SSPA) System 2017 / 2019 Calendar

Primary 5 Secondary School Places Allocation System Seminar 20-4-2018 Secondary School Places Allocation (SSPA) System 2017 / 2019 Calendar June P.5 Sept. P.6 Dec. 2018 June Nov. Exam 2 Exam 1 Result Result Submission Submission Secondary School Places Allocation (SSPA) System Calendar Dec. or Feb. 9/7 Release of Cross Net Application Allocation Results 15 April 11-12/7 Registration 3/1 – 17/1 Central Discretionary Place Allocation 2019 Jan. July April June Exam 2 Final Exam Result Submission Our school net : Kwun Tong District Application for cross-net allocation who are moving home or are already in another district will be opened Dec. 2018 or Feb. 2019 Submit supporting document copy of stamped tenancy, agreement, tenant’s rent card issued by the public housing authorities, demand note for rates / gas bill / electricity bill / residential phone bill / water bill Two Stages Discretionary Central Allocation Place (DP) (CA) Choose 2 schools (Part A: Choose 3 schs.) -unrestricted -unrestricted (Part B: Choose 30 schs.) Application: Kwun Tong District 3-17 Jan., 2019 Application: Interview: 15-27April, 2019 Feb. / Mar., 2019 Discretionary Place Stage 3/1 - 17/1 (DP) Districts: >30% No restriction No. of schools to choose: <Type 1> Not more than 2 schools The lists of participating schools accepting application for S1 DP, parents may refer to the Handbook for Application for S1 Discretionary Places distributed to the primary schools. (Gov. Schs. / Aided Schs.) <Type 2> Direct Subsidy Scheme (DSS) Sec. Sch. Not Participating in Sec. Sch. -

PDF Document

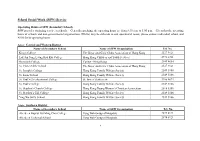

School Social Work (SSW) Service Operating Hours of SSW (Secondary School) SSW provides stationing service at schools. Generally speaking, the operating hours are from 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Given that the operating hours of schools and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) may be different to suit operational needs, please contact individual school and NGO for its operating hours. Area : Central and Western District Name of Secondary School Name of SSW Organisation Tel. No. King's College The Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs Association of Hong Kong 2527 9121 Lok Sin Tong Leung Kau Kui College Hong Kong Children and Youth Services 2572 2311 Raimondi College Caritas - Hong Kong 2843 4684 St. Clare's Girls' School The Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs Association of Hong Kong 2527 9121 St. Joseph’s College Hong Kong Family Welfare Society 2549 5106 St. Louis School Hong Kong Family Welfare Society 2549 5106 St. Paul’s Co-educational College St. James’ Settlement 3106 4673 St. Paul’s College Hong Kong Family Welfare Society 2549 5106 St. Stephen's Church College Hong Kong Young Women’s Christian Association 2818 8356 St. Stephen’s Girl College Hong Kong Family Welfare Society 2549 5106 Ying Wa Girl’s School Hong Kong Family Welfare Society 2549 5106 Area : Southern District Name of Secondary School Name of SSW Organisation Tel. No. Aberdeen Baptist Lui Ming Choi College Tung Wah Group of Hospitals 2874 8121 Aberdeen Technical School Tung Wah Group of Hospitals 2874 8121 1 Name of Secondary School Name of SSW Organisation Tel. No. Caritas Chong Yuet Ming Secondary -

2019 HKDSE School Candidates

Ref.: DSE/CR 3/2018 8 June 2018 Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination 2019 Examination Circular No. (10) 2017/2018 Registration of School Candidates for Category C (Other Languages) Subjects 1. Registration of School Candidates (a) Registration for Category C (Other Languages) subjects of the 2019 Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination (HKDSE) (i.e. November 2018 series) will be accepted from 20 June to 9 July 2018. Schools presenting students for the Examination are required to register with the HKEAA via the Registration System at the HKDSE Examination Online Services (https://www.hkdse.hkeaa.edu.hk). Hardcopy of entry forms will not be accepted. (b) All six Category C subjects, viz. French, German, Hindi, Japanese, Spanish and Urdu, will be offered in the November 2018 series examination. The AS level question papers of Cambridge Assessment International Education (Cambridge International) will be used in the Category C examinations. For details about the selection of subjects, please refer to Annex 1. (c) Before submitting their students’ registration entries to the HKEAA, schools should make sure that all students entering for the Category C (Other Languages) subject examinations are bona fide Secondary 6 students in the school year 2018/2019. (d) Schools should remind their students that they must abide by the regulations laid down in the HKDSE Examination Regulations and ‘Instructions to Candidates’ for Category C (Other Languages) subjects when taking the examinations. Candidates in breach of any examination regulations or requirements are subject to penalty. 2. Examination Fee Waiver for the 2019 HKDSE School Candidates The Legislative Council has approved a financial commitment for paying examination fees for eligible school candidates sitting for the 2019 HKDSE as a one-off measure. -

SAP Crystal Reports

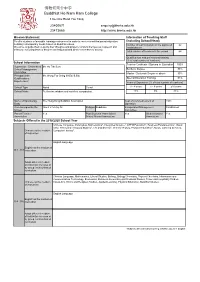

佛教何南金中學 Buddhist Ho Nam Kam College 3 Ko Chiu Road Yau Tong 23400871 [email protected] 23473665 http://www.bhnkc.edu.hk Mission Statement Information of Teaching Staff To offer students a favorable learning environment in order to receive a well-balanced education (including School Head) befitting contemporary needs based on Buddhist values. Number of teaching posts in the approved 62 We strive to guide them to purify their thoughts and properly conduct themselves in speech and establishment behavior, nurturing them to become well-adjusted and sincere members of society. Total number of teachers in the school 68 Qualifications and professional training (% of total number of teachers) School Information Teacher Certificate / Diploma in Education 100% Supervisor / Chairman of Mr. Ho Tak Sum School Management Bachelor Degree 98% Committee Master / Doctorate Degree or above 35% Principal (with Mr. Wong Tsz Ching (M.Ed, B.Ed) Qualifications / Special Education Training 58% Experiences) Years of Experience (% of total number of teachers) School Type Aided Co-ed 0 - 4 years 5 - 9 years ≥10 years School Motto To illumine wisdom and manifest compassion. 11% 8% 81% Name of Sponsoring The Hong Kong Buddhist Association Year of Commencement of 1988 Body Operation Area Occupied by the About 5250 Sq. M Religion Buddhism Incorporated Management Established School Committee Parent-Teacher Yes Past Students' Association / Yes Student Union / Yes Association School Alumni Association Association Subjects Offered in the 2019/2020 School Year Chinese Language, Putonghua, Mathematics*, Integrated Science*, STEM Education*, Business Fundamentals*, Visual Arts*, Ethics and Religious Studies*, Life and Society*, Chinese History, Physical Education*, Music, Catering Services, Chinese as the medium Computer Literacy*. -

Elsie Tu Papers

Hong Kong Baptist University Library Special Collections & Archives Elsie Tu Papers Record Group No. 13 [December 13, 2019] Tu, Elsie (杜 葉 錫 恩) ,1913 – 2015 Papers; 1951-2015, n.d. 35 Boxes (4 RC, 31 DC; 19.9 cubic feet), Books, Oversize Material, Photo Albums, Photographs, Posters Restrictions: Anyone using this collection must sign an Agreement to use the Elsie Tu Papers. No material except published works such as books, pamphlets, press release and newspaper clippings may be photocopied. Biography Full name: Elsie Tu Birth date: June 2, 1913, in Newcastle upon Tyne, England Family: Parents: John Hume, Florence Lydia Hume Siblings: Ethel, Dorothy, Albert Collingwood Marital Status: Married to William Elliott in 1946 in England Married to Andrew Hsueh-kwei Tu (杜 學 魁) on June 13, 1985 in Hong Kong Children: Yau Ling Tu Education: 1925-1928 Benwell Secondary Girl’s School, England 1928-1932 Heaton Secondary School, England 1932-1937 Armstrong College, University of Durham (renamed as Newcastle University later) Career: 1937-1947 Teaching in England 1947 Joined Christian Missions in Many Lands, went to Jiangxi ( 江 西 ), China as a missionary 1948-1951 Stationed in Yifeng ( 宜 豐 ) near Nanchang ( 南 昌 ), involved in teaching and evangelistic activities 1951-1955 Left China to Hong Kong in February 1951 and continued her missionary work among the poor. Started a tent school in September 1954 and later founded a school with Andrew Hsueh-Kwei Tu (杜 學 魁) in September 1955. Left Hong Kong to England in November 1955 1954-2000 Supervisor and teacher of Mu Kuang English School ( 慕 光 中 學 ) 1956- Resigned from the Christian Missions in Many Lands and returned to Hong Kong in May 1956.