Sonorant Extension, Transitional Vowels, and Gesture Sharing: an Acoustic Study of Russian Clusters Peter Staroverov Rutgers, T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sonorants, Fricatives and a Tonogenetic Typology

Sonorants, fricatives and a tonogenetic typology Gwendolyn Hyslop University of Oregon 1. Introduction and background While some phonological mechanisms underlying tonogenesis have been understood for some time (e.g. Maspero (1912), Haudricourt (1954), inter alia ) ongoing research in tonogenesis suggests that the full picture is more complex than previous studies have indicated. For example, though it is generally established that voiceless initials yield high pitch register, voiced initials yield low pitch register and coda consonants condition pitch contour, the order in which segments undergo tonogenesis has barely been addressed. Additionally, tone may be conditioned by other factors such as pre-aspiration or vowel quality, amongst others. The classical account of tonogenesis has been the model proposed by Haudricourt (1954) for Vietnamese. Diffloth (1989) reanalyzed the model to take register differences into account and Thurgood (2002) suggested updating our model of (Vietnamese) tonogenesis based on laryngeal features, arguing that intermediate stages existed. For example, voiced obstruents would condition breathy voice on their following vowel, which would in turn condition low tone. It remains to be seen, however, how much predictive power this model has, especially given recent research on tonogenesis in Kurtöp and the other East Bodish languages (Hyslop 2009, 2010), showing that tonogenesis targets sonorants and then fricatives before developing following obstruent consonants, a finding similar to that for Athabaskan (Kingston 2005, 2007). ‘Tone’ refers to the primary use of fundamental frequency to make lexical/grammatical contrasts in a given language (other acoustic cues may be involved, such as voice quality, duration, etc.). This definition includes most languages which have been classified as ‘pitch- accent’, as well as (possibly) languages which are considered to have a ‘register’ distinction (cf. -

Sonority As a Primitive: Evidence from Phonological Inventories

Sonority as a Primitive: Evidence from Phonological Inventories Ivy Hauser University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 1. Introduction The nature of sonority remains a controversial subject in both phonology and phonetics. Previous discussions on sonority have generally been situated in synchronic phonology through syllable structure constraints (Clements, 1990) or in phonetics through physical correlates to sonority (Parker, 2002). This paper seeks to examine the sonority hierarchy through a new dimension by exploring the relationship between sonority and phonological inventory structure. The investigation will shed light on the nature of sonority as a phonological phenomenon in addition to addressing the question of what processes underlie the formation and structure of speech sound inventories. This paper will examine a phenomenon present in phonological inventories that has yet to be discussed in previous literature and cannot be explained by current theories of inventory formation. I will then suggest implications of this phenomenon as evidence for sonority as a grammatical primitive. The data described here reveals that sonority has an effect in the formation of phonological inventories by determining how many segments an inventory will have in a given class of sounds (voiced fricatives, etc.). Segment classes which are closest to each other along the sonority hierarchy tend to be correlated in size except upon crossing the sonorant/obstruent and consonant/vowel boundaries. This paper argues that inventories are therefore composed of three distinct classes of obstruents, sonorants, and vowels which independently determine the size and structure of the inventory. The prominence of sonority in inventory formation provides evidence for the notion that sonority is a phonological primitive and is not simply derived from other aspects of the grammar or a more basic set of features. -

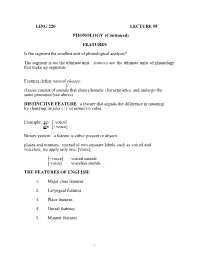

LING 220 LECTURE #8 PHONOLOGY (Continued) FEATURES Is The

LING 220 LECTURE #8 PHONOLOGY (Continued) FEATURES Is the segment the smallest unit of phonological analysis? The segment is not the ultimate unit: features are the ultimate units of phonology that make up segments. Features define natural classes: ↓ classes consist of sounds that share phonetic characteristics, and undergo the same processes (see above). DISTINCTIVE FEATURE: a feature that signals the difference in meaning by changing its plus (+) or minus (-) value. Example: tip [-voice] dip [+voice] Binary system: a feature is either present or absent. pluses and minuses: instead of two separate labels, such as voiced and voiceless, we apply only one: [voice] [+voice] voiced sounds [-voice] voiceless sounds THE FEATURES OF ENGLISH: 1. Major class features 2. Laryngeal features 3. Place features 4. Dorsal features 5. Manner features 1 1. MAJOR CLASS FEATURES: they distinguish between consonants, glides, and vowels. obstruents, nasals and liquids (Obstruents: oral stops, fricatives and affricates) [consonantal]: sounds produced with a major obstruction in the oral tract obstruents, liquids and nasals are [+consonantal] [syllabic]:a feature that characterizes vowels and syllabic liquids and nasals [sonorant]: a feature that refers to the resonant quality of the sound. vowels, glides, liquids and nasals are [+sonorant] STUDY Table 3.30 on p. 89. 2. LARYNGEAL FEATURES: they represent the states of the glottis. [voice] voiced sounds: [+voice] voiceless sounds: [-voice] [spread glottis] ([SG]): this feature distinguishes between aspirated and unaspirated consonants. aspirated consonants: [+SG] unaspirated consonants: [-SG] [constricted glottis] ([CG]): sounds made with the glottis closed. glottal stop [÷]: [+CG] 2 3. PLACE FEATURES: they refer to the place of articulation. -

78. 78. Nasal Harmony Nasal Harmony

Bibliographic Details The Blackwell Companion to Phonology Edited by: Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume and Keren Rice eISBN: 9781405184236 Print publication date: 2011 78. Nasal Harmony RACHEL WWALKER Subject Theoretical Linguistics » Phonology DOI: 10.1111/b.9781405184236.2011.00080.x Sections 1 Nasal vowel–consonant harmony with opaque segments 2 Nasal vowel–consonant harmony with transparent segments 3 Nasal consonant harmony 4 Directionality 5 Conclusion ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Notes REFERENCES Nasal harmony refers to phonological patterns where nasalization is transmitted in long-distance fashion. The long-distance nature of nasal harmony can be met by the transmission of nasalization either to a series of segments or to a non-adjacent segment. Nasal harmony usually occurs within words or a smaller domain, either morphologically or prosodically defined. This chapter introduces the chief characteristics of nasal harmony patterns with exemplification, and highlights related theoretical themes. It focuses primarily on the different roles that segments can play in nasal harmony, and the typological properties to which they give rise. The following terminological conventions will be assumed. A trigger is a segment that initiates nasal harmony. A target is a segment that undergoes harmony. An opaque segment or blocker halts nasal harmony. A transparent segment is one that does not display nasalization within a span of nasal harmony, but does not halt harmony from transmitting beyond it. Three broad categories of nasal harmony are considered in this chapter. They are (i) nasal vowel–consonant harmony with opaque segments, (ii) nasal vowel– consonant harmony with transparent segments, and (iii) nasal consonant harmony. Each of these groups of systems show characteristic hallmarks. -

An Autosegmental Account of Melodic Processes in Jordanian Rural Arabic

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3592 & P-ISSN: 2200-3452 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au An Autosegmental Account of Melodic Processes in Jordanian Rural Arabic Zainab Sa’aida* Department of English, Tafila Technical University, P.O. Box 179, Tafila 66110, Jordan Corresponding Author: Zainab Sa’aida, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This study aims at providing an autosegmental account of feature spread in assimilatory situations Received: October 02, 2020 in Jordanian rural Arabic. I hypothesise that in any assimilatory situation in Jordanian rural Arabic Accepted: December 23, 2020 the undergoer assimilates a whole or a portion of the matrix of the trigger. I also hypothesise Published: January 31, 2021 that assimilation in Jordanian rural Arabic is motivated by violation of the obligatory contour Volume: 10 Issue: 1 principle on a specific tier or by spread of a feature from a trigger to a compatible undergoer. Advance access: January 2021 Data of the study were analysed in the framework of autosegmental phonology with focus on the notion of dominance in assimilation. Findings of the study have revealed that an undergoer assimilates a whole of the matrix of a trigger in the assimilation of /t/ of the detransitivizing Conflicts of interest: None prefix /Ɂɪt-/, coronal sonorant assimilation, and inter-dentalization of dentals. However, partial Funding: None assimilation occurs in the processes of nasal place assimilation, anticipatory labialization, and palatalization of plosives. Findings have revealed that assimilation occurs when the obligatory contour principle is violated on the place tier. Violation is then resolved by deletion of the place node in the leftmost matrix and by right-to-left spread of a feature from rightmost matrix to leftmost matrix. -

Becoming Sonorant

Becoming sonorant Master Thesis Leiden University Theoretical and Experimental Linguistics Tom de Boer – s0728020 Supervisor: C. C. Voeten, MA July 2017 Table of Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Sonority ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The usage of [sonorant] ................................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Influence of sonority ..................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Structure ....................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Database study...................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 4 2.2 Method ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Results ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3.1 Global Results ....................................................................................................................... -

The Sonority Sequencing Principle in Sanandaji/Erdelani Kurdish an Optimality Theoretical Perspective

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 2, No. 5; 2012 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Sonority Sequencing Principle in Sanandaji/Erdelani Kurdish An Optimality Theoretical Perspective Muhamad Sediq Zahedi1, Batool Alinezhad1 & Vali Rezai1 1 Departement of General Linguistics, Faculty of Foreign Languages, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran Correspondence: Muhamad Sediq Zahedi, Departement of General Linguistics, Faculty of Foreign Languages, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 27, 2012 Accepted: July 25, 2012 Online Published: September 26, 2012 doi:10.5539/ijel.v2n5p72 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v2n5p72 Abstract The aim of this article is to study Sanandaji consonant clusters in relation with their conformity to the principle of sonority sequencing. Analyzing the data provided in this paper, we found out that, of the three kinds of consonant clusters existing in all languages, only core clusters—clusters that conform to the sonority sequencing principle (SSP)—are found in Sanandaji, and therefore the arrangement and combination of segments to make syllables in this dialect of Kurdish is absolutely governed by the SSP. Applying principles of Optimality Theory on the data, the relative ranking of syllable structure constraints is determined, the outcome of which is deriving surface phonotactic patterns through the interaction of markedness and faithfulness constraints. Keywords: consonant cluster, sonority, optimality theory, Sanandaji/Erdelani Kurdish 1. Introduction Sonority has been subject to many studies for more than a century. Despite giving various, different definitions for it, most linguists agree on the important role of sonority in syllable structure (Morelli, 2003). -

Linguistics 120A B

Linguistics 120A B. Hayes Phonology I UCLA More Practice with Features This exercise is optional. Answers at the end. To do the following problems, open FeaturePad and select the English phoneme inventory. 1. [u, U, o, ] are deleted in word-final position after [p, b, m] (modeled on Telugu). 2. [i, , e, , æ] become [y, Y, O, œ, Ø] after [w, „] (modeled on a rule of Yana). 3. [n, t, d] become [, k, g] before [k, g] (place assimilation, found in many languages). 4. [S, Z, tÉS, dÉZ] become [s, z, tÉs, dÉz] when [s, z] follow later in the same word. (modeled on Navajo) 5. [T, ] become [f, v] in all contexts (found in the speech of many small children). 6. [f, T, s, S] become [v, , z, Z] when surrounded by vowels (modeled on Italian). 7. [, ] become [e, i] before another vowel (modeled on British English). 8. [s, z] become [tÉs, dÉz] after [n] (English dialects: dance, lens) 9. [l, ®, w, j] become [l, ®, u, i] in word final position after a consonant. (modeled on Russian) 10. [t, d] become [] if preceded by a vowel or [®] and followed by a vowel. To make the rule simple, you may assume that there are no underlying forms in which [t,d] are preceded by [w, „, j, h]. (actual rule of American English) 11. [p, t, tÉS, k] are aspirated word-initially. (modeled on English) 12. [t, d, s, z ] become [tÉ, dÉ, , ] before [i, j] (modeled on Japanese) 13. [m] becomes [M] before [f, v] (real rule of English) Now go to the Phoneme menu (top of the screen) and switch to the phoneme inventory of Spanish. -

Statistical NLP Articulatory System Places of Articulation Labial Place Coronal Place

Speech in a Slide Statistical NLP Spring 2010 Frequency gives pitch; amplitude gives volume s p ee ch l a b amplitude Frequencies at each time slice processed into observation vectors Lecture 8: Speech Signal Dan Klein – UC Berkeley …………………………………………….. a12 a13 a12 a14 a14 ……….. Articulatory System Places of Articulation Nasal cavity alveolar post-alveolar/palatal dental Oral cavity velar Pharynx uvular labial Vocal folds (in the larynx) pharyngeal Trachea laryngeal/glottal Lungs Sagittal section of the vocal tract (Techmer 1880) Text from Ohala, Sept 2001, from Sharon Rose slide Figure thanks to Jennifer Venditti Labial place Coronal place alveolar post-alveolar/palatal Bilabial: dental labiodental p, b, m Labiodental: Dental: bilabial f, v th/dh Alveolar: t/d/s/z/l/n Post: sh/zh/y Figure thanks to Jennifer Venditti Figure thanks to Jennifer Venditti 1 Dorsal Place Space of Phonemes velar Velar: uvular k/g/ng pharyngeal Standard international phonetic alphabet (IPA) chart of consonants Figure thanks to Jennifer Venditti Manner of Articulation Space of Phonemes In addition to varying by place, sounds vary by manner Stop: complete closure of articulators, no air escapes via mouth Oral stop: palate is raised (p, t, k, b, d, g) Nasal stop: oral closure, but palate is lowered (m, n, ng) Fricatives: substantial closure, turbulent: (f, v, s, z) Approximants: slight closure, sonorant: (l, r, w) Standard international phonetic alphabet (IPA) chart of consonants Vowels: no closure, sonorant: (i, e, a) Vowel Space “She just had a baby” -

Chapter on Phonology

13 The (American) English Sound System 13.1a IPA Chart Consonants: Place & Manner of Articulation bilabial labiodental interdental alveolar palatal velar / glottal Plosives: [+voiced] b d g [voiced] p t k Fricatives: [+voiced] v ð z ž [voiced] f θ s š h Affricates: [+voiced] ǰ [voiced] č *Nasals: [+voiced] m n ŋ *Liquids: l r *Glides: w y *Syllabic Nasals and Liquids. When nasals /m/, /n/ and liquids /l/, /r/ take on vowellike properties, they are said to become syllabic: e.g., /ļ/ and /ŗ/ (denoted by a small line diacritic underneath the grapheme). Note how token examples (teacher) /tičŗ/, (little) /lIt ļ/, (table) /tebļ/ (vision) /vIžņ/, despite their creating syllable structures [CVCC] ([CVCC] = consonantvowel consonantconsonant), nonetheless generate a bisyllabic [CVCV] structure whereby we can ‘clapout’ by hand two syllables—e.g., [ [/ ti /] [/ čŗ /] ] and 312 Chapter Thirteen [ [/ lI /] [/ tļ /] ], each showing a [CVCC v] with final consonant [C v] denoting a vocalic /ŗ/ and /ļ/ (respectively). For this reason, ‘fluid’ [Consonantal] (vowellike) nasals, liquids (as well as glides) fall at the bottom half of the IPA chart in opposition to [+Consonantal] stops. 13.1b IPA American Vowels Diphthongs front: back: high: i u ay I ә U oy au e ^ o ε * ] low: æ a 13.1c Examples of IPA: Consonants / b / ball, rob, rabbit / d / dig, sad, sudden / g / got, jogger / p / pan, tip, rapper / t / tip, fit, punter / k / can, keep / v / vase, love / z / zip, buzz, cars / ž / measure, pleasure / f / fun, leaf / s / sip, cent, books / š / shoe, ocean, pressure / ð / the, further / l / lip, table, dollar / č / chair, cello / θ / with, theory / r / red, fear / ǰ / joke, lodge / w / with, water / y / you, year / h / house / m / make, ham / n / near, fan / ŋ / sing, pink The American English Sound System 313 *Note: Many varieties of American English cannot distinguish between the ‘open‘O’ vowel /]/ e.g., as is sounded in caught /k]t/ vs. -

Sonority Sequencing Principle in Sabzevari Persian: a Constraint-Based Approach

Open Linguistics 2019; 5: 434–465 Research Article Mufleh Salem M. Alqahtani* Sonority Sequencing Principle in Sabzevari Persian: A Constraint-Based Approach https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2019-0024 Received October 11, 2018; accepted October 15, 2019 Abstract: This study sheds light on the relationship between the Sonority Sequencing Principle (SSP) and syllable structure in Sabzevari, a Persian vernacular spoken in the Sabzevar area of Northeast Iran. Optimality Theory (OT), as a constraint-based approach, is utilized to scrutinize sonority violation and its repair strategies. The results suggest that obedience to the SSP is mandatory in Sabzevari, as shown through the treatment of word-final clusters in Standard Persian words which violate the SSP. These consonant clusters are avoided in Sabzevari by two phonological processes: vowel epenthesis and metathesis. Vowel epenthesis is motivated by final consonant clusters of the forms /fricative+coronal nasal/, /plosive+bilabial nasal/, /fricative+bilabial nasal/, /plosive+rhotic/, /fricative+rhotic/, and /plosive+lateral/. Metathesis, as another repair strategy for sonority sequencing violations, occurs when dealing with final consonant clusters of the forms /plosive+fricative/ and / fricative+lateral/. Keywords: Sabzevari syllable structure; SSP violation; vowel epenthesis; metathesis; Optimality Theory (OT) 1 Introduction Studies conducted on sonority demonstrate a significant role in the organization of syllables in natural languages (Clements 1990; Laks 1990; Klein 1990). Consonants and vowels in most languages are combined to form syllables while other sonorant consonants can represent nuclei in languages including English (Treiman et al., 1993; Ridouane 2008), German (Roach 2002; Ridouane 2008), Czech (Roach 2002; Ridouane 2008), and Barber (Ridouane 2008).1 Their arrangement is such that sonority is highest at the peak and drops from the peak towards the margins (Clements 1990). -

Introductory Phonology

9781405184120_1_pre.qxd 06/06/2008 09:47 AM Page iii Introductory Phonology Bruce Hayes A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405184120_4_C04.qxd 06/06/2008 09:50 AM Page 70 4 Features 4.1 Introduction to Features: Representations Feature theory is part of a general approach in cognitive science which hypo- thesizes formal representations of mental phenomena. A representation is an abstract formal object that characterizes the essential properties of a mental entity. To begin with an example, most readers of this book are familiar with the words and music of the song “Happy Birthday to You.” The question is: what is it that they know? Or, to put it very literally, what information is embodied in their neurons that distinguishes a knower of “Happy Birthday” from a hypothetical person who is identical in every other respect but does not know the song? Much of this knowledge must be abstract. People can recognize “Happy Birth- day” when it is sung in a novel key, or by an unfamiliar voice, or using a different tempo or form of musical expression. Somehow, they can ignore (or cope in some other way with) inessential traits and attend to the essential ones. The latter include the linguistic text, the (relative) pitch sequences of the notes, the relative note dura- tions, and the musical harmonies that (often tacitly) accompany the tune. Cognitive science posits that humans possess mental representations, that is, formal mental objects depicting the structure of things we know or do. A typical claim is that we are capable of singing “Happy Birthday” because we have (during childhood) internalized a mental representation, fairly abstract in character, that embodies the structure of this song.