Arxiv:1602.05364V1 [Astro-Ph.GA]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Methyl Formate

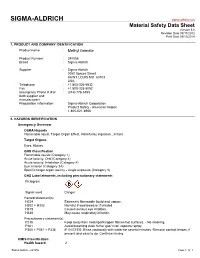

SIGMA-ALDRICH sigma-aldrich.com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 5.0 Revision Date 09/17/2012 Print Date 03/13/2014 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name : Methyl formate Product Number : 291056 Brand : Sigma-Aldrich Supplier : Sigma-Aldrich 3050 Spruce Street SAINT LOUIS MO 63103 USA Telephone : +1 800-325-5832 Fax : +1 800-325-5052 Emergency Phone # (For : (314) 776-6555 both supplier and manufacturer) Preparation Information : Sigma-Aldrich Corporation Product Safety - Americas Region 1-800-521-8956 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Emergency Overview OSHA Hazards Flammable liquid, Target Organ Effect, Harmful by ingestion., Irritant Target Organs Eyes, Kidney GHS Classification Flammable liquids (Category 1) Acute toxicity, Oral (Category 4) Acute toxicity, Inhalation (Category 4) Eye irritation (Category 2A) Specific target organ toxicity - single exposure (Category 3) GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram Signal word Danger Hazard statement(s) H224 Extremely flammable liquid and vapour. H302 + H332 Harmful if swallowed or if inhaled H319 Causes serious eye irritation. H335 May cause respiratory irritation. Precautionary statement(s) P210 Keep away from heat/sparks/open flames/hot surfaces. - No smoking. P261 Avoid breathing dust/ fume/ gas/ mist/ vapours/ spray. P305 + P351 + P338 IF IN EYES: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. Continue rinsing. HMIS Classification Health hazard: 2 Sigma-Aldrich - 291056 Page 1 of 7 Chronic Health Hazard: * Flammability: 4 Physical hazards: 0 NFPA Rating Health hazard: 2 Fire: 4 Reactivity Hazard: 0 Potential Health Effects Inhalation May be harmful if inhaled. Causes respiratory tract irritation. Skin Harmful if absorbed through skin. -

United States

Patented Jan. 6, 1931 1,787,483 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE BURRITT SAMUEL LACY, OF RED BANK, NEWJERSEY, AssIGNOR, BY MEsNE AssIGN MENTS, TO THE ROESSLER & BASSLACHER CEEMICAL COMPANY, OF NEW YORK, N. Y., A. CORPORATION OF DELAWARE PROCESS OR BE PRODUCTION OF FOR AMIDE NoDrawing. Application filed November 17, 1925. Serial No. 89,708. This invention relates to the formation of the reverse not only of this reaction but also formamide from ammonia and carbon mon of the analogous reaction with the methyl oxide. While this reaction is not unknown, compound is catalyzed by sodium ethylate the literature is full of records of unsuccess resp. sodium methylate, thus:- 50 5 highful attempts pressures and and work expensive involving equipment. the use Asof C. CO+CHOH=HCOOCH. an example of these unsuccessful attempts However, in carrying out reaction C and that of Meyer & Orthner, Ber. 54B 1705 the analogous reaction between ethyl alco (1921) at 125 atmospheres with clay as a cat hol and carbon monoxide, not only did Staeh 10 alyst is most conclusive. The result has been ler use enormous pressures, but the time con a complete lack of commercial development. sumed by the operation made it very imprac Aside from the attempts to make form tical for commercial use. Thus Staehler used amide by the direct reaction between carbon a pressure of 300 atmospheres in reacting monoxide and ammonia, there have been de with ethyl alcohol to form ethyl formate, 15 scribed in the literature reactions by which and one of 160 atmospheres in reacting with 60 it might be considered possible to obtain methyl alcohol to form methyl formate; formamide indirectly from carbon monox while there was required a reaction period of ide and ammonia as the ultimate raw ma 14 days at room temperature to produce a terials, but the conditions under which these 45% of theory conversion of ethyl alcohol to 20 reactions occurred were such as to discour ethyl formate, and one of 8 days (partly at 65 age employing them for the commercial pro 100-120° C. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Steps Toward CO2 Reduction to Methanol via Electrochemical Cascade Catalysis Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4wx6g1vm Author Mercer, Ian Patrick Publication Date 2020 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Steps Toward CO2 Reduction to Methanol via Electrochemical Cascade Catalysis THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Chemistry by Ian Patrick Mercer Dissertation Committee: Professor Jenny Y. Yang, Chair Professor William J. Evans Professor Andy S. Borovik 2020 © 2020 Ian Patrick Mercer ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements iv Abstract v Chapter 1: Methyl Formate and Formaldehyde Reduction by Metal Hydrides 1 Chapter 2: Synthesis of Group 8 Metal Complexes of LDMA for the Study of Outer Sphere Interactions 25 Conclusion 33 Experimental 34 References 37 iii Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my committee, especially my chair, Professor Jenny Y. Yang. Her commitment to science, mentoring, and ‘doing the right thing’ will forever inspire me. Financial support was provided by the University of California, Irvine and US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences Awards DE-SC0012150 and DE- 0000243266. iv Abstract of the Thesis Steps Toward CO2 Reduction to Methanol via Electrochemical Cascade Catalysis by Ian Patrick Mercer Master of Science in Chemistry University of California, Irvine, 2020 Professor Jenny Y. Yang, Chair Research on two independent projects is presented: (1) Homogeneous cascade catalysis has been used for the hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol as it allows for rational tuning of catalyst reactivity and lower reaction temperatures compared to heterogeneous catalysis. -

Process for Producing Methyl Methacrylate Verfahren Zur Herstellung Von Methylmethacrylat Procede Pour La Fabrication De Methacrylate De Methyle

~™ II 1 1 III II II 1 1 II II I Ml II I II I II (19) J European Patent Office Office europeen des brevets (11) EP 0 406 676 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publicationation and mention (51 ) |nt. CI.6: C07C 69/54, C07C 67/20 of the grant of the patent: 27.03.1996 Bulletin 1996/13 (21) Application number: 90112194.7 (22) Date of filing: 27.06.1990 (54) Process for producing methyl methacrylate Verfahren zur Herstellung von Methylmethacrylat Procede pour la fabrication de methacrylate de methyle (84) Designated Contracting States: • Ebata, Shuji, DE ES FR GB IT NL C/o Mitsubishi Gas Chem. Com. Tayuhama, Niigata-shi, Niigata-ken (JP) (30) Priority: 04.07.1989 JP 171190/89 (74) Representative: Turk, Gille, Hrabal, Leifert (43) Date of publication of application: Brucknerstrasse 20 09.01.1991 Bulletin 1991/02 D-40593 Dusseldorf (DE) (73) Proprietor: MITSUBISHI GAS CHEMICAL (56) References cited: COMPANY, INC. DE-A- 3 436 608 Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo (JP) • PATENT ABSTRACTS OF JAPAN vol. 14, no. 68 (72) Inventors: (C- 686)(401 1 ), 8 February 1 990; & JP-A-1 290653 • Higuchi, Hirofumi, (MITSUBISHI GAS CHEM) 22.11. 1989 C/o Mitsubishi Gas Chem. Com. Tayuhama, Niigata-shi, Niigata-ken (JP) Remarks: • Kida, Koichi, The file contains technical information submitted C/o Mitsubishi Gas Chem. Com. after the application was filed and not included in this Tayuhama, Niigata-shi, Niigata-ken (JP) specification CO CO CO o Note: Within nine months from the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to the European patent granted. -

CO2 Vapormate Application Manual

→ VAPORMATE™ manual for fumigation VAPORMATE™ Manual for fumigation. 02 Contents Contents 03 Contents. 4 Important notice 11 5.5 Safety equipment 14 9. VAPORMATE efficacy 20 13. Monitoring equipment 11 5.5.1 Full-face respirator 14 9.1 Mode of action 20 13.1 Multi-gas detectors 5 1. Introduction 11 5.5.2 Self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) 11 5.5.3 Gas detection systems 14 9.2 Commodities that can be fumigated 20 14. Monitoring frequency 5 2. Product stewardship 11 5.6 Material compatibility 15 9.3 Dose calculation 11 5.7 Public safety 21 15. Fumigation 6 3. Background 16 10. Residues 12 5.8 Personal safety 6 3.1 Ethyl formate 21 16. Preparing for ventilation 12 5.9 Confined spaces hazard 17 11. Application technology 6 3.2 VAPORMATE 13 5.10 Handling emergencies 17 11.1 Portable electric vaporiser (PEV) 22 17. Troubleshooting 7 4. Physical and chemical properties 13 5.11 Emergency procedures 17 11.2 Fans 22 17.1 Valves 17 11.3 Temperature control 22 17.2 Cylinder condition 8 5. Safety 13 6. Legal requirements 22 17.3 Failure to control the target pests 8 5.1 Toxicity 18 12. Fumigation preparation 14 7. Environment 22 17.4 Non-target organisms 9 5.1.1 Short term (acute) exposure 18 12.1 Risk assessment 9 5.1.2 Long term (chronic) exposure 9 5.1.3 First aid 14 8. Cylinder safety 18 12.2 Fumigation chamber 9 5.2 Flammability 14 8.1 Cylinder storage 18 12.3 Leak testing 10 5.2.1 Fire prevention 14 8.2 Cylinder transport 19 12.4 Monitoring hoses 10 5.2.2 Fire fighting 14 8.3 Cylinder leaks 19 12.5 Placarding and securing fumigated 10 5.3 Asphyxiation areas 11 5.4 Low temperatures 04 Important notice Introduction, product stewardship 05 Important notice. -

Process of Formic Acid Production by Hydrolysis

(19) TZZ ¥_T (11) EP 2 747 883 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: B01J 14/00 (2006.01) C07C 51/09 (2006.01) 15.02.2017 Bulletin 2017/07 C07C 53/02 (2006.01) B01J 10/00 (2006.01) B01D 3/10 (2006.01) C07C 51/44 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 12751504.7 (86) International application number: (22) Date of filing: 27.08.2012 PCT/EP2012/066622 (87) International publication number: WO 2013/030162 (07.03.2013 Gazette 2013/10) (54) PROCESS OF FORMIC ACID PRODUCTION BY HYDROLYSIS OF METHYL FORMATE VERFAHREN ZUR HERSTELLUNG VON AMEISENSÄURE DURCH HYDROLYSE VON METHYLFORMIAT PROCÉDÉ DE PRODUCTION D’ACIDE FORMIQUE PAR HYDROLYSE DE FORMIATE DE MÉTHYLE (84) Designated Contracting States: • TREJBAL, Jiri AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB 278 01 Kralupy nad Vltavou (CZ) GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO • ROOSE, Peter PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR 9831 Sint-Martens-Latem (BE) (30) Priority: 27.08.2011 US 201161528204 P (74) Representative: Gevers Patents Intellectual Property House (43) Date of publication of application: Holidaystraat 5 02.07.2014 Bulletin 2014/27 1831 Diegem (BE) (73) Proprietor: Taminco (56) References cited: 9000 Gent (BE) WO-A1-00/39067 US-A- 4 262 140 US-B1- 6 713 649 US-B2- 6 696 603 (72) Inventors: • PASEK, Josef 160 00 Praha 6 (CZ) Note: Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the Implementing Regulations. -

Ethyl Alcohol. Fined in § 170.3(O)(12) of This Chapter

Food and Drug Administration, HHS § 184.1295 NARA, call 202–741–6030, or go to: http:// in this section do not exist or have www.archives.gov/federallregister/ been waived. codeloflfederallregulations/ [52 FR 25976, July 10, 1987, as amended at 73 ibrllocations.html. FR 8607, Feb. 14, 2008] (c) Dill and its derivatives are used as flavoring agents and adjuvants as de- § 184.1293 Ethyl alcohol. fined in § 170.3(o)(12) of this chapter. (d) The ingredients are used in food (a) Ethyl alcohol (ethanol) is the at levels not to exceed good manufac- chemical C2H5OH. turing practice. (b) The ingredient meets the speci- (e) [Reserved] fications of the ‘‘Food Chemicals (f) Prior sanctions for these ingredi- Codex,’’ 4th ed. (1996), p. 136, which is ents different from the uses established incorporated by reference in accord- in this section do not exist or have ance with 5 U.S.C. 552(a) and 1 CFR been waived. part 51. Copies are available from the National Academy Press, Box 285, 2101 [42 FR 14653, Mar. 15, 1977, as amended at 42 Constitution Ave. NW., Washington, FR 55205, Oct. 14, 1977; 49 FR 5612, Feb. 14, DC 20055 (Internet address http:// 1984; 64 FR 1760, Jan. 12, 1999] www.nap.edu), or may be examined at § 184.1287 Enzyme-modified fats. the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition’s Library, Food and Drug Ad- (a) Enzyme-modified refined beef fat, ministration, 5100 Paint Branch Pkwy., enzyme-modified butterfat, and en- College Park, MD 20740, or at the Na- zyme-modified steam-rendered chicken tional Archives and Records Adminis- fat are prepared from refined beef fat; tration (NARA). -

Methyl Formate Mfm

METHYL FORMATE MFM CAUTIONARY RESPONSE INFORMATION 4. FIRE HAZARDS 7. SHIPPING INFORMATION 4.1 Flash Point: -26°F C.C. 7.1 Grades of Purity: Technical, practical, and Common Synonyms Liquid Colorless Pleasant odor 4.2 Flammable Limits in Air: 5%-22.7% spectro grades: all 97.5+% Formic acid, methyl ester 4.3 Fire Extinguishing Agents: Dry 7.2 Storage Temperature: <85°F Mixes with water. Flammable, irritating vapor is produced. Boiling point chemical, alcohol foam, carbon dioxide 7.3 Inert Atmosphere: No requirement is 88°F. 4.4 Fire Extinguishing Agents Not to Be 7.4 Venting: Pressure-vacuum Used: Water may be ineffective. 7.5 IMO Pollution Category: D Evacuate. 4.5 Special Hazards of Combustion Keep people away. Products: Not pertinent 7.6 Ship Type: 2 Shut off ignition sources. Call fire department. 4.6 Behavior in Fire: Vapor is heavier than 7.7 Barge Hull Type: Currently not available Notify local health and pollution control agencies. air and may travel considerable distance to a source of ignition and flash back. FLAMMABLE. 8. HAZARD CLASSIFICATIONS Fire 4.7 Auto Ignition Temperature: 853°F Containers may explode in fire. 8.1 49 CFR Category: Flammable liquid Flashback along vapor trail may occur. 4.8 Electrical Hazards: Currently not 8.2 49 CFR Class: 3 Vapor may explode if ignited in an enclosed area. available Extinguish with dry chemicals, alcohol foam, or carbon dioxide. 4.9 Burning Rate: 2.5 mm/min. 8.3 49 CFR Package Group: I Water may be ineffective on fire. 4.10 Adiabatic Flame Temperature: Currently 8.4 Marine Pollutant: No Cool exposed containers with water. -

Working Fluid Selection for Space-Based Two-Phase Heat Transport Systems

NBSIR 88-3812 Working Fluid Selection for Space-Based Two-Phase Heat Transport Systems Mark O. McLinden U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards Gaithersburg, MD 20899 May 1988 Issued August 1988 75 Years Stimulating America's Progress 1913-1988 Prepared for: National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center NBSIR 88-3812 WORKING FLUID SELECTION FOR SPACE-BASED TWO-PHASE HEAT TRANSPORT SYSTEMS Mark O. McLinden U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards Gaithersburg, MD 20899 May 1988 Issued August 1988 Prepared for: National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, C. William Verity, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS, Ernest Ambler, Director , ABSTRACT The working fluid for externally-mounted, space-based two-phase heat transport systems is considered. A sequence of screening criteria involving freezing and critical point temperatures and latent heat of vaporization and vapor density are applied to a data base of 860 fluids. The thermal performance of the 52 fluids which pass this preliminary screening are then ranked according to their impact on the weight of a reference system. Upon considering other non-thermal criteria ( f lagimability toxicity and chemical stability) a final set of 10 preferred fluids is obtained. The effects of variations in system parameters is investigated for these 10 fluids by means of a factorial design. i * . I . INTRODUCTION In order to remove the heat generated by electronics and other payloads on spacecraft some type of heat transport system is required. The heat generating equipment is typically attached to a 'cold plate'. -

VAPOR-LIQUID EQUILIBRIUM DATA COLLECTION Chemistry Data Series

J. Gmehling U. Onken VAPOR-LIQUID EQUILIBRIUM DATA COLLECTION Esters Supplement 2 Chemistry Data Series Vol. I, Part 5b Published by DECHEMA Gesellschaft fur Chemische Technik und Biotechnologie e. V. Executive Editor: Gerhard Kreysa Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; de tailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de ISBN: 3-89746-041-6 © DECH EMA Gesellschaft fOr Chemische Te chnik und Biotechnologie e. V. Postfach 15 01 04, D-60061 Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2002 Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschutzt. Alle Rechte, auch die der Obersetzung, des Nachdrucks und der Vervielfi:Htigung des Buches oder Teilen daraus sind vorbehalten. Kein Teil des Werkes darf ohne schriftliche Genehmigung der DECHEMA in irgendeiner Form (Fotokopie, Mikrofilm oder einem anderen Verfahren), auch nicht fOr Zwecke der Un terrichtsgestaltung, reproduziert oder unter Verwendung elektronischer Systeme verarbei tet, vervielfaltigt oder verbreitet werden. Die Herausgeber Obernehmen fOr die Richtigkeit und Vollstandigkeit der publizierten Daten keinerlei Gewahrleistung. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, including those of translation, reprinting, reproduction by photo copying machine or similar means. No partof this work may be reproduced, processed or distributed in any form, not even for teaching purposes - by photocopying, microfilm or other processes, or implemented in electronic information storage and retrieval systems - without the written permission of the publishers. The publishers accept no liability for the accuracy and completeness of the published data. This volume of the Chemistry Data Series was printed using acid-free paper. -

ICH Guideline Q3C (R7) on Impurities – Support Document 3 Toxicological Data for Class 3 Solvents

19 October 2018 EMA/CHMP/ICH/735038/2018 Committee for Human Medicinal Products ICH guideline Q3C (R6) on impurities – support document 3: toxicological data for class 3 solvents Step 5 Release for information October 2018 30 Churchill Place ● Canary Wharf ● London E14 5EU ● United Kingdom Telephone +44 (0)20 3660 6000 Facsimile +44 (0)20 3660 5505 Send a question via our website www.ema.europa.eu/contact An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2018. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL FOR HARMONISATION OF TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS FOR PHARMACEUTICALS FOR HUMAN USE TOXICOLOGICAL DATA FOR CLASS 3 SOLVENTS Q3C SUPPORT DOCUMENT 3 Published on the ICH website on 3 October 2018 30 Churchill Place ● Canary Wharf ● London E14 5EU ● United Kingdom Telephone +44 (0)20 3660 6000 Facsimile +44 (0)20 3660 5505 Send a question via our website www.ema.europa.eu/contact An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2018. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Q3C SUPPORT DOCUMENT 3 Document History Document History Q3C Support This document was originally the Appendix 6 of Document 3 the Q3C Step 2 draft Guideline from 1996 which contained the summaries of the toxicity data from which the PDEs for Class 3 solvents were derived. The Appendix 6 was later published as part of Pharmeuropa, Vol. 9, No. 1, Supplement, April 1997, and the ICH Q3C Guideline references to this publication. For the convenience of the stakeholders, ICH has published the Appendix 6 as a Support Document on the ICH public website on 3 October 2018. -

Toxicological and Regulatory Information Supporting the Registration of VAPORMATETM As a Grain Fumigant for Farm Storages

From: E.J. Wright, M.C. Webb and E. Highley, ed., Stored grain in Australia 2003. Proceedings of the Australian Postharvest Technical Conference, Canberra, 25–27 June 2003. CSIRO Stored Grain Research Laboratory, Canberra. Toxicological and regulatory information supporting the registration of VAPORMATETM as a grain fumigant for farm storages V.S. Haritos,1 K.A. Damcevski and G. Dojchinov Stored Grain Research Laboratory, CSIRO Entomology, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601 Abstract. VAPORMATETM, a BOC Ltd product composed of ethyl formate 16.7% by weight in carbon dioxide, is cur- rently under evaluation as a grain fumigant for farm silos. The research has aimed at devising an application system for the mixture that will maximise the concentration of ethyl formate in the bin but minimise the loss to grain sorption. Also, we are investigating the optimal amount and exposure period to achieve high mortality of a range of tolerant stored grain pests. VAPORMATETM appears very favourable in terms of data to support registration of the product, such as mamma- lian toxicology, residue analysis methods, low risk of environmental impacts, and occupational health and safety aspects of ethyl formate, and its natural occurrence. Ethyl formate is far less acutely toxic to mammals, including humans, than dichlorvos and phosphine, two of the main treatments that are currently available for farm storages. Ethyl formate also has a higher occupational exposure limit (100 ppm versus 0.3 ppm for phosphine and 0.1 ppm for dichlorvos). Ethyl for- mate is a natural component of many foods and the hydrolysis products formed in the human body are formic acid and ethanol which are identical with products formed endogenously.