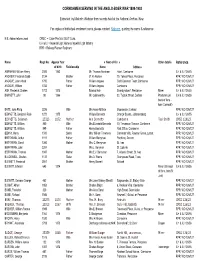

APPENDICES a & B: COUNTY CHARACTERISATIONS and COUNTY TOTALS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2015 is an index calculated from 37 indicators measuring deprivation in its broadest sense. The overall IMD 2015 score combines scores from seven areas (called domains), which are weighted as follows: • Income (22.5%) • Employment (22.5%) • Health and disability (13.5%) • Education, skills and training (13.5%) • Barriers to housing and services (9.3%) • Crime (9.3%) • Living environment (9.3%) Overall in 2015, Shropshire County was a relatively affluent area and was ranked as the 129th most deprived County out of all 149 Counties in England. The IMD is based on sub-electoral ward areas called Lower level Super Output Areas (LSOAs), which were devised in the 2001 Census. Each LSOA is allocated an IMD score, which is weighted on the basis of its population. There were 32,844 LSOAs in England; of these only 9 in Shropshire County fell within the most deprived fifth of all LSOAs in England. These LSOAs were located within the electoral wards of Market Drayton West, Oswestry South, Oswestry West, in North Shropshire; Castlefields and Ditherington, Harlescott, Meole, Monkmoor and Sundorne in Shrewsbury and Ludlow East in South Shropshire. To get a more meaningful local picture, each LSOA in Shropshire County was ranked from 1 (most deprived in Shropshire) to 192 (least deprived in Shropshire). Shropshire LSOAs were then divided into local deprivation quintiles which are used for profiling and monitoring of health and social inequalities in Shropshire County (1 representing the most deprived fifth of local areas and 5 the least). Figure 1 shows the most deprived areas shaded in the darkest colour – these tend to be situated around the major settlements in Shropshire. -

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS CORNWALL COUNCIL VOTING AREA Referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union 1. A referendum is to be held on THURSDAY, 23 JUNE 2016 to decide on the question below : Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? 2. The hours of poll will be from 7am to 10pm. 3. The situation of polling stations and the descriptions of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows : No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 301 STATION 2 (AAA1) 1 - 958 CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 301/1 STATION 1 (AAM4) 1 - 212 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 302 CUDDRA W I HALL (AAA2) 1 - 430 BUCKLERS LANE HOLMBUSH ST AUSTELL PL25 3HQ 303 BETHEL METHODIST CHURCH (AAB1) 1 - 1,008 BROCKSTONE ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DW 304 BISHOP BRONESCOMBE SCHOOL (AAB2) 1 - 879 BOSCOPPA ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DT KATE KENNALLY Dated: WEDNESDAY, 01 JUNE, 2016 COUNTING OFFICER Printed and Published by the COUNTING OFFICER ELECTORAL SERVICES, ST AUSTELL ONE STOP SHOP, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 305 SANDY HILL ACADEMY (AAB3) 1 - 1,639 SANDY HILL ST AUSTELL PL25 3AW 306 STATION 2 (AAG1) 1 - 1,035 THE COMMITTEE ROOM COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK ROAD PL25 5DR 306/1 STATION 1 (APL3) 1 - 73 THE COMMITTEE ROOM CORNWALL COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK -

NOTICE of ELECTION Shropshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parish Listed Below

NOTICE OF ELECTION Shropshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parish listed below Number of Parish Parish Councillors to be elected Alberbury with Cardeston Parish Council Nine 1. Forms of nomination for the above election may be obtained from the Clerk to the Parish Council, or the Returning Officer at the Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6ND who will, at the request of an elector for any electoral area prepare a nomination paper for signature. 2. Nomination papers must be hand-delivered to the Returning Officer, Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6ND on any day after the date of this notice but no later than 4 pm on Thursday, 8th April 2021. Alternatively, candidates may submit their nomination papers at the following locations on specified dates, between the times shown below: Shrewsbury Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, SY2 6ND 9.00am – 5.00pm Weekdays from Tuesday 16th March to Thursday 1st April. 9.00am – 7.00pm Tuesday 6th April and Wednesday 7th April. 9.00am – 4.00pm Thursday 8th April. Oswestry Council Chamber, Castle View, Oswestry, SY11 1JR 8.45am – 6.00pm Tuesday 16th March; Thursday 25th March and Wednesday 31st March. Wem Edinburgh House, New Street, Wem, SY4 5DB 9.15am – 4.30pm Wednesday 17th March; Monday 22nd March and Thursday 1st April. Ludlow Helena Lane Day Care Centre, 20 Hamlet Road, Ludlow, SY8 2NP 8.45am – 4.00pm Thursday 18th March; Wednesday 24th March and Tuesday 30th March. Bridgnorth Bridgnorth Library, 67 Listley Street, Bridgnorth, WV16 4AW 9.45am – 4.30pm Friday 19th March; Tuesday 23rd March and Monday 29th March. -

S519 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

S519 bus time schedule & line map S519 Shrewsbury - Newport View In Website Mode The S519 bus line (Shrewsbury - Newport) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Newport: 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM (2) Shrewsbury: 7:25 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest S519 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next S519 bus arriving. Direction: Newport S519 bus Time Schedule 38 stops Newport Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Bus Station, Shrewsbury Tuesday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Post O∆ce, Shrewsbury Wednesday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Gasworks, Castle Fields Thursday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Social Services O∆ces, Castle Fields Friday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM St Michael's Terrace, Shrewsbury Saturday Not Operational Flax Mill, Ditherington Spring Gardens, Shrewsbury The Coach Ph, Ditherington S519 bus Info Six Bells Ph, Ditherington Direction: Newport Stops: 38 The Heathgates Ph, Sundorne Trip Duration: 61 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Shrewsbury, Post O∆ce, Albert Road Jct, Sundorne Shrewsbury, Gasworks, Castle Fields, Social Services O∆ces, Castle Fields, Flax Mill, Ditherington, The Coach Ph, Ditherington, Six Bells Ph, Ditherington, Robsons Stores, Sundorne The Heathgates Ph, Sundorne, Albert Road Jct, Sundorne Road, Shrewsbury Sundorne, Robsons Stores, Sundorne, Ta Centre, Sundorne, Sports Village, Sundorne, Featherbed Ta Centre, Sundorne Lane Jct, Sundorne, Junction, U∆ngton, Abbey, U∆ngton, Kennels, Roden, Nurseries, Roden, Hall, Sports Village, Sundorne Roden, Hall, Roden, Talbot Fields, -

Cornish Conections Surname Sorted.Xlsx

CORNISHMEN SERVING IN THE ANGLO-BOER WAR 1899-1902 Extracted by Malcolm Webster from records held at the National Archive, Kew For copies of individual enrolment cards, please contact Malcolm, quoting the name & reference N.B. Abbreviations used CMSC = Cape Medical Staff Corp. ILH & ILI = Imperial Light Horse & Imperial Light Infantry RPR = Railway Pioneer Regiment Name Regt. No. Approx Year « Next of Kin » Other details Reference of birth Relationship Name Address ABRAHAM, William Henry 2585 1862 Mr. Thomas Abraham Hotel, Camborne ILH & ILI 126/55 ANDREW, Frederick Dabb 2124 Brother J?.H. Andrew 10, Tolves Place, Penzance RPR: WO 126/127 ANGOVE, John Alfred 1750 Father William Angove Croft Common Troon,Camborne RPR: WO 126/127 ANGOVE, William 1743 Father William Angove Camborne RPR: WO 126/127 ASH, Frederick Charles 1702 1875 Edward Ash Shandyndom?, Penzance Miner ILH & ILI 126/55 BARNETT, John 98 1866 Mr. Goldsworthy 33, Tyzack Street, Durban Plasterer (on ILH & ILI 126/55 back of form - born Cornwall) BATE, John Philip 2226 Wife Mrs Annie M Bate Moorswater, Liskard RPR: WO 126/127 BENNETTS, Benjamin Rule 1272 1875 William Bennetts Orange Scouts, Johannesburg ILH & ILI 126/55 BENNETTS, Solomon 25323 1872 Mother Ann Bennetts Camborne Tool Smith CMSC 126/23 BENNETTS, William 860 Wife Mrs Elizabeth Bennetts 10, Trevenson Terrace, Camborne RPR: WO 126/127 BENNETTS, William 849 Father Henry Bennetts Post Office, Camborne RPR: WO 126/127 BENNY, Harry 1500 Sister Mrs. William Trewhella Clements Villa, Rowsan Grove, Lelant RPR: WO 126/127 BERRYMAN, Arthur 1191 Father William Berryman Porthleat, Zennor RPR: WO 126/127 BERRYMAN, David 1360 Mother Mrs. -

The Shropshire Enlightenment: a Regional Study of Intellectual Activity in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries

The Shropshire Enlightenment: a regional study of intellectual activity in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries by Roger Neil Bruton A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham January 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The focus of this study is centred upon intellectual activity in the period from 1750 to c1840 in Shropshire, an area that for a time was synonymous with change and innovation. It examines the importance of personal development and the influence of intellectual communities and networks in the acquisition and dissemination of knowledge. It adds to understanding of how individuals and communities reflected Enlightenment aspirations or carried the mantle of ‘improvement’ and thereby contributes to the debate on the establishment of regional Enlightenment. The acquisition of philosophical knowledge merged into the cultural ethos of the period and its utilitarian characteristics were to influence the onset of Industrial Revolution but Shropshire was essentially a rural location. The thesis examines how those progressive tendencies manifested themselves in that local setting. -

14Th May 2021 Shrewsbury Town Council Parish Council Guildhall Our Ref: 21/05142/NEWNUM Frankwell Quay Your Ref: Shrewsbury Shropshire SY3 8HQ

Ms Helen Ball Date: 14th May 2021 Shrewsbury Town Council Parish Council Guildhall Our Ref: 21/05142/NEWNUM Frankwell Quay Your Ref: Shrewsbury Shropshire SY3 8HQ Dear Ms Helen Ball SHROPSHIRE COUNCIL STREET NAMING AND NUMBERING SECTIONS 17,18 AND 19 PUBLIC HEALTH ACT 1925 CASE REFERENCE: 21/05142/NEWNUM PROPOSED STREET NAME: Holyoake Close DEVELOPMENT SITE E J Holyoake, Heathgates Works, 67A Ditherington LOCATION: Road, Shrewsbury The Street Naming and Numbering Department would like to propose the following suggestion for the new street name at the development site location shown above. Holyoake Close The proposed name is has been suggested by the developer and the following supporting information provided. "After WWII a local railway signalman (my great-grandad) Frank Holyoake and his wife May built the shop at 65 Ditherington Road for my returning great uncles Dennis and Leslie to work as greengrocers . My Grandad Ernest started the coach building business just behind in a small workshop. From the 50s onwards the coach building business grew quickly and Grandad slowly purchased the bakers' buildings and other various workshops. When Dennis decided to emigrate to Australia, Ernest also purchased the shop at the front of the site and the tailor's house which he and my grandmother lived in until their deaths". The proposed suggestion is regarded to be suitable with in the terms of the Street Naming and Numbering Policy. I have attached a location/layout plan for your assistance. If the Town/Parish Council would like to make any further comment regarding this proposal please reply by 01st June 2021. -

First Penzance

First Penzance - Sheffield CornwallbyKernow 5 via Newlyn - Gwavas Saturdays Ref.No.: PEN Service No A1 5 5 A1 5 5 A1 5 A1 A1 A1 M6 M6 M6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Penzance bus & rail station 0835 0920 1020 1035 1120 1220 1235 1320 1435 1635 1740 1920 2120 2330 Penzance Green Market 0838 0923 1023 1038 1123 1223 1238 1323 1438 1638 1743 1923 2123 2333 Penzance Alexandra Inn 0842 - - 1042 - - 1242 - 1442 1642 1747 1926 2126 2336 Alverton The Ropewalk - 0926 1026 - 1126 1226 - - - - - - - - Lansdowne Estate Boswergy - - - - - - - 1327 - - - - - - Newlyn Coombe - - - - - - - 1331 - - - - - - Newlyn Bridge 0846 0930 1030 1046 1130 1230 1246 1333 1446 1646 1751 1930 2130 2340 Gwavas Chywoone Roundabout - 0934 1034 - 1134 1234 - 1337 - - - 1951 2151 0001 Gwavas Chywoone Crescent - - - - - 1235 - 1338 - - - 1952 2152 0002 Gwavas Chywoone Avenue Roundabout - 0937 1037 - 1137 1237 - 1340 - - 1755 1952 2152 0002 Gwavas crossroads Chywoone Hill 0849 - - 1049 - - 1249 - 1449 1649 1759 - - - Lower Sheffield - 0941 1041 - 1141 1241 - 1344 - - - - - - Sheffield 0852 - - 1052 - - 1252 - 1452 1652 1802 1955 2155 0005 Paul Boslandew Hill - 0944 1044 - 1144 1244 - 1347 - - - 1958 2158 0008 ! - Refer to respective full timetable for full journey details Service No A1 5 A1 5 5 A1 5 5 A1 A1 A1 A1 M6 M6 M6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sheffield 0754 - 1025 - - 1225 - - 1425 1625 1825 1925 1955 2155 0005 Lower Sheffield - 0941 - 1041 1141 - 1241 1344 - - - - 1955 2155 0005 Paul Boslandew Hill 0757 0944 - 1044 1144 - 1244 1347 - - - - 1958 2158 0008 Gwavas crossroads Chywoone Avenue -

2.1 the Liberties and Municipal Boundaries.Pdf

© VCH Shropshire Ltd 2020. This text is supplied for research purposes only and is not to be reproduced further without permission. VCH SHROPSHIRE Vol. VI (ii), Shrewsbury Sect. 2.1, The Liberties and Municipal Boundaries This text was originally drafted by the late Bill Champion in 2012. It was lightly revised by Richard Hoyle in the summer and autumn of 2020. The text on twentieth-century boundary changes is his work. The final stages of preparing this version of the text for web publication coincided with the Coronavirus pandemic of 2020. It was not possible to access libraries and archives to resolve a small number of outstanding queries. When it becomes possible again, it is proposed to post an amended version of this text on the VCH Shropshire website. In the meantime we welcome additional information and references, and, of course, corrections. In some cases the form of references has been superseded. Likewise, some cross-references are obsolete. It is intended that this section will be illustrated by a map showing the changing boundary which will be added into the text at a later date. October 2020 © VCH Shropshire Ltd 2020. This text is supplied for research purposes only and is not to be reproduced further without permission. 1 © VCH Shropshire Ltd 2020. This text is supplied for research purposes only and is not to be reproduced further without permission. 2.1. The Liberties and Municipal Boundaries The Domesday ‘city’ (civitas) of Shrewsbury included nine hides identifiable as the townships of its original liberty. To the south of the Severn they included Sutton, Meole Brace, Shelton, and Monkmeole (Crowmeole), and to the north Hencott.1 The location of a further half-hide, belonging to St Juliana’s church, was described by Eyton as ‘doubtful’,2 but may refer to the detached portions of St Juliana’s in Shelton.3 More obscure, as leaving no later parochial trace, was a virgate in Meole Brace which belonged to St Mary’s church.4 The Domesday liberties, however, were not settled. -

Chairman's Report / Community Updates

CARN BREA PARISH CONSEL PLU CARN BREA SUMMER 2017 Chairman’s REPORT / Your Councillors COMMUNITY UPDATES Elections Please be aware that you Green Infrastructure for Following the recent local can search for planning Growth elections Carn Brea Parish applications in your area by A project team from Cornwall now has a new Council for using your postcode, or street Council have been discussing the next four years, made up name, in the Cornwall Council with us a plan to identify urban from a mix of experienced and Planning website. Carn Brea green spaces (parks, amenity brand new councillors. We all Parish Council Planning areas, closed churchyards, look forward to doing our best Committee meets on the last roadside verges) that could for the people of the Parish. Thursday of each month, with benefit from the planting of native trees, wildflower areas, At county level we see the our Agenda on our website Barncoose Ward or the creation of wildlife Cllr CEN Bickford - 01209 719533 return of experience in Cllr just prior to the day. Sycamores, 12 Rosewarne Mews, Tehidy Rd, Camborne TR14 8LN ponds. Funded mainly by David Ekinsmyth (Illogan) Cllr C Jordan - 01209 313220 Devolution the EU, with support from Email: [email protected] and the new in Cllr Robert 8 Harrison Gardens, Illogan, Redruth, Cornwall, TR15 3JR the University of Exeter Hendry (Four Lanes) and Cllr P Sheppard - Day 01209 710079 We continue to discuss and Cornwall Council, the Email: [email protected] Cllr Philip Desmonde (Pool Riviera, Lighthouse Hill, Portreath, Cornwall, TR16 4LH with Cornwall Council the areas under consideration & Tehidy). -

Core Strategy

Shropshire Local Development Framework : Adopted Core Strategy March 2011 “A Flourishing Shropshire” Shropshire Sustainable Community Strategy 2010-2020 Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Spatial Portrait 7 Shropshire in 2010 7 Communities 9 Economy 10 Environment 13 Spatial Zones in Shropshire 14 3 The Challenges We Face 27 Spatial Vision 28 Strategic Objectives 30 4 Creating Sustainable Places 34 Policy CS1: Strategic Approach 35 Policy CS2: Shrewsbury Development Strategy 42 Policy CS3: The Market Towns and Other Key Centres 48 Policy CS4: Community Hubs and Community Clusters 61 Policy CS5: Countryside and Green Belt 65 Policy CS6: Sustainable Design and Development Principles 69 Policy CS7: Communications and Transport 73 Policy CS8: Facilities, Services and Infrastructure Provision 77 Policy CS9: Infrastructure Contributions 79 5 Meeting Housing Needs 82 Policy CS10: Managed Release of Housing Land 82 Policy CS11: Type and Affordability of Housing 85 Policy CS12: Gypsies and Traveller Provision 89 6 A Prosperous Economy 92 Policy CS13: Economic Development, Enterprise and Employment 93 Policy CS14: Managed Release of Employment Land 96 Policy CS15: Town and Rural Centres 100 Policy CS16: Tourism, Culture and Leisure 104 7 Environment 108 Policy CS17: Environmental Networks 108 Policy CS18: Sustainable Water Management 111 Policy CS19: Waste Management Infrastructure 115 Policy CS20: Strategic Planning for Minerals 120 Contents Page 8 Appendix 1: Saved Local and Structure Plan Policies replaced by the Core Strategy 126 9 Glossary 138 -

Minutes of the Meeting of Alberbury with Cardeston Parish Council

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF ALBERBURY WITH CARDESTON PARISH COUNCIL Held by Zoom teleconference on 15th February 2021 at 7.30pm Present: R Kynaston (Chair), R Griffiths, M Tomlins, D Parry, Mrs J Wilson, C Bourne, R Davies Mrs K Stokes, Mrs S Evans and Clr. E Potter Apologies: PC R Cookson Historical note: The global pandemic caused by the COVID 19 Coronavirus was still continuing, with approaching 120,000 UK deaths since February 2020, and at the time of this meeting England was still in a third complete lockdown. An unprecedented public vaccination process was underway with 15 million persons having received a first dose at this point. 1574 MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETING Minutes 1566 to 1573 of the Meeting held on 11th January 2021 were proposed for acceptance by D Parry, seconded by R Griffiths, and approved unanimously. 1575 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST Mr Kynaston was the applicant in the Planning item 8d, and would take no part in any discussion on that, and Mrs Evans declared a personal interest in 8c as related to the applicant. 1576 CLERKS REPORT The Clerk reported that it was still planned to hold elections in May and that the present policy of the Government was to not allow virtual meetings after April, but this was under review based on how the COVID emergency continued. He was still waiting for a date for the Speed Indicator Device pole in Alberbury to be installed. He had also completed a Finance Update Course recently and had issued a number of procedures and statements since, without comment by members.