About Gillows' Windsor and Common Chairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY of MINNESOTA Nflv 1 4 1971Extension BULLETIN 402-1977 C

NflV 1 4 1971eXTENSION BULLETIN 402-1977 c: ,<% o;o ;o'"Tl :S:• ::X: (0 ·-<~ -.l 1:>- AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA CAINIIIINIG Many beautiful old cane chairs may have been discarded because of broken cane. These chairs can be restored and used in today's home. Weaving new 0 0 0 cane seats or inserting cane webbing requires time and patience, but it is not a difficult job. This bulletin includes information and directions for the following types of caning: 0 DETERMINING CANE SIZE 1. Hand woven cane seats for chairs or stools with 0 small holes drilled through the frame. 2. Cane webbing or pressed cane that can be 0 used for chairs, stools, cabinet doors, folding screens, etc. A groove is needed for this type of caning. Cane is the outside part of rattan, a palm which Equipment Needed is imported from India, China, and the Malay Penin 1. Chair or stool with holes. 2. Correct size cane. sula. All cane is glossy on one side. The glossy side 3. Wooden pegs (about 15 to 20). There are regular is the top or outside. pegs for caning; however, you can whittle your own, or use golf tees. 4. Icepick or awl. 5. Scissors. Hand Woven Seats 6. Sponge. 7. Pan of hot water. 8. Old towel. Cane is sold in bundles of approximately 1,000 Preparation of Chair feet. One hank will weave two to three average size 1. Save a small piece of weaving cane and binding seats. (For weaving chair seats cane is available in cane from the old seat to use in ordering new cane. -

From the Shop

From The Shop The newsletter of the Lehigh Valley Woodworker’s Guild Issue 10.2007 Alcock from NJ a few months ago that was pure hand tool cutting. Frank Rauscher’s approach is geared Next Meeting: October 16th, 2007 (3rd Tuesday!) toward the hobbyist – using power carving devices, Location: Lehigh Co. Senior Center adding some detail with the carver or, if you prefer, 1633 Elm Street some detail via woodburning, and getting some Allentown, PA beautiful and fine results. Speakers and topics: • Annual Guild Woodworking contest • BRING IN THE BLOCKS PLEASE! September Meeting Highlights Frank Rauscher - Carving Frank had everyone gather round and demonstrated techniques in a close up enough manner so all could see what he was doing. He was still going at 10:00, and folks were still listening… Kingfisher as powercarved and woodburned by Frank Frank brought a few examples of his work – a Rauscher. Kingfisher, a Cardinal, and a rainbow trout. Apparently Frank ad not a lot of experience doing fish and this was Well, we are operating on total recall. Do not ask me a new project for him, and looked to be an excellent what I did with 6 pages of notes from Frank Rauscher’s first attempt. When describing the fish and birds. Frank excellent presentation of power carving, but they are explained that you want to create an effect og life and gone and likely among paperwork I had discarded moving, and so the birds heads are turned in a lifelike inadvertently. So much for cleaning up! But I have a way and not straight on, and the fish is curved as good pictorial record of the meeting, and should be though swimming. -

Seat Weaving

S E A T W E A V I N G D Y P R R Y L . A E u e r v so r o Ma n u a l Tra n n ol et I ll no s S p i f i i g , $ i , i i , a d I s r tor D ar t nt E sth e t a n d I n d ustr al E d u cat o n n n t u c , ep m e ic i i , um m er u a rte rs Th e Un ver s t o h c a o S $ , i i y f C i g TH E MANUAL A RTS P R E S S PE R I A N O , I LLI O I S 1 C t 1 9 1 7 b V opyr igh , , L Da P r r . y e y FO R E WO R D Woodworking shops in manual t r ain ing schools far outnumber r as t hose for othe manual acti vities , and a result , cou rses in wood work h ave come to be te r med the st able cou r ses in a handwork r . r no t cu r iculum However , experience in woodwo k alone is su f i t r r f cien , and needs to be supplemented by othe and more va ied act ivities to give to the boy a p r oper foun dation fo r choice o f vocation . A defin i t e way to p r od uce necessa r y va r iety as applied t o wood r r t h e f r t wo k , especially i f woodwo k is only cou rse o fe ed , is h ru th e of use such medi ums as cane , reed , rush , splints and allied materials r in cor elation with the wood . -

17606 Chanceh.Pdf

Downloaded from: http://bucks.collections.crest.ac.uk/ The Working Landscape This document is protected by copyright. It is published with permission and all rights are reserved. Usage of any items from Buckinghamshire New University’s institutional repository must follow the usage guidelines. Any item and its associated metadata held in the institutional repository is subject to Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Please note that you must also do the following; • the authors, title and full bibliographic details of the item are cited clearly when any part of the work is referred to verbally or in the written form • a hyperlink/URL to the original Insight record of that item is included in any citations of the work • the content is not changed in any way • all files required for usage of the item are kept together with the main item file. You may not • sell any part of an item • refer to any part of an item without citation • amend any item or contextualise it in a way that will impugn the creator’s reputation • remove or alter the copyright statement on an item. If you need further guidance contact the Research Enterprise and Development Unit [email protected] 1.6 The working landscape Reader in the History and Theory of Design, Dr Helena Chance • Buckinghamshire New University This article is my contribution to the Chilterns Conservation Board (CCB) Landscape Al Conservation Action Plan (LCAP) which is the guiding document for the Chalk,le Cherries n d and Chairs Landscape Partnership Scheme. -

Product Cleaning and Maintenance Care

Product Cleaning and Maintenance Care The best spaces manifest quality in proportion and material—from KnollTextiles colorful textiles, soft felts and leathers to wood, laminates and Knoll Office engineered polymers. Materials like these evoke simplicity and balance, KnollExtra coexisting with furniture to achieve Florence Knoll’s ideal—the spirit KnollStudio DatesWeiser of “total design.” Our extensive range of materials and dedication to SpinneyBeck | FilzFelt quality can complete your workspace, whether raw or refined. Muuto This product cleaning and maintenance care guide refers to the entire constellation of Knoll products. For additional Muuto cleaning guidance, please refer to Muuto’s Product Fact Sheets at: http://download.muuto.com/MediaLibrary/Product-Fact-Sheet Furniture that is comprised of multiple materials may require multiple cleaning and maintenance protocols. Refer to Knoll Price Lists to determine the component material and fabric options where applicable. Refer to this guide for how to clean and maintain each surface. Tested Disinfectant Formulas While Knoll cannot guarantee the efficacy of these products, when properly used in accordance with the manufacturers’ directions for use and dilution, they will not cause harm to the standard finishes below. These products have been tested on all standard Knoll Office veneers, laminates, paints, glass, aluminum and plated finishes. These products have been tested on all standard KnollStudio laminates, paints, glass, aluminum and plated finishes. These tested cleaners apply to these standard finishes only. (Additional testing is necessary for KnollStudio veneers as well as specialty finishes, DatesWeiser and Muuto.) + Envirox® H2Orange2 Concentrate 117 + Virox™ Accelerated™ Hydrogen Peroxide 5 + Envirox® EvolveO2™ ( GN×2 technology ) #1, Multi-Purpose Cleaner and Degreaser The Center for Disease Control (CDC) advises social distancing and handwashing to help prevent the spread of COVID-19. -

Design Ireland

At-a-glance LIVE TALKS | IN-STORE DEMONSTRATIONS | HANDS ON WORKSHOPS March 8 TH TUESDAY MEET THE MAKER John Hanly, Weaving Craft 1-2pm & 6-7pm 9 TH WEDNESDAY DEMO Adam Frew, Throwing Pots MEET THE MAKER Catherine Keenan, Glass Craft 1-2pm & 6-7pm 10TH THURSDAY DEMO Adam Frew, Throwing Pots MEET THE MAKER Catherine Keenan, Glass Craft 1-2pm & 6-7pm 11TH FRIDAY DEMO Adam Frew, Throwing Pots MEET THE MAKER Catherine Keenan, Glass Craft 1-2pm & 6-7pm 12TH SATURDAY DEMO Bunbury Boards, Wood Turning 13TH SUNDAY DEMO Bunbury Boards, Wood Turning 7th March – 14TH MONDAY DEMO Bunbury Boards, Wood Turning 24th April 2016 Joe Hogan The Great Heal’s Adam Frew Bodging Race 15TH TUESDAY DEMO me&him&you, Screen Printing FEATURING MEET THE MAKER John Hanly, Weaving Craft 1-2pm & 6-7pm 16TH WEDNESDAY DEMO me&him&you, Screen Printing MEET THE MAKER Scribble & Stone, Jewellery Design 1-2pm & 6-7pm Design Ireland 196 Tottenham Court Road, 17TH THURSDAY DEMO Joe Hogan, Basket Making 11am-9pm; MEET THE MAKER Scribble & Stone, London W1T 7LQ 7th – 28th March Jewellery Design 1-2pm & 6-7pm; PARTY Heal’s Craft Market Party 6-9pm 18TH FRIDAY DEMO Joe Hogan, Basket Making www.heals.com MEET THE MAKER Scribble & Stone, Jewellery Design 1-2pm & 6-7pm Modern Craft Market TO BOOK WORKSHOP TICKETS VISIT www.heals.com/events 01 Heal's MCM Brochure - 6pp Cover.indd 1 17/02/2016 11:44 19TH SATURDAY DEMO Joe Hogan, Basket Making 7 TH THURSDAY DEMO CSWA_, Domestic Cup Casting 12.30-2pm & 5-8pm 20TH SUNDAY DEMOWelcome Arran Street East, Throwing Pots 8 TH FRIDAY WORKSHOP -

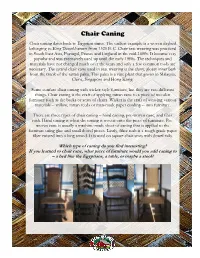

Chair Caning

Chair Caning Chair caning dates back to Egyptian times. The earliest example is a woven daybed belonging to King Tutankhamen from 1325 B. C. Chair seat weaving was practiced in South East Asia, Portugal, France and England in the mid-1600s. It became very popular and was extensively used up until the early 1900s. The techniques and materials have not changed much over the years and only a few common tools are necessary. The strand chair cane used in seat weaving is the shiny, glossy inner bark from the trunk of the rattan palm. This palm is a vine plant that grows in Malaysia, China, Singapore and Hong Kong. Some confuse chair caning with wicker-style furniture, but they are two different things. Chair caning is the craft of applying rattan cane to a piece of wooden furniture such as the backs or seats of chairs. Wicker is the craft of weaving various materials -- willow, rattan reeds or man-made paper cording -- into furniture. There are three types of chair caning – hand caning, pre-woven cane, and fiber rush. Hand caning is when the caning is woven onto the piece of furniture. Pre- woven cane is usually a machine-made sheet of caning that is applied to the furniture using glue and small dowel pieces. Lastly, fiber rush is a tough grade paper fiber twisted into a long strand. It is used on square chair seats with dowel rails. Which type of caning do you find interesting? If you learned to chair cane, what piece of furniture would you add caning to – a bed like the Egyptians, a table, or maybe a stool? Chair Caning Word Find Puzzle Find these words in the puzzle below. -

Woodworking Glossary, a Comprehensive List of Woodworking Terms and Their Definitions That Will Help You Understand More About Woodworking

Welcome to the Woodworking Glossary, a comprehensive list of woodworking terms and their definitions that will help you understand more about woodworking. Each word has a complete definition, and several have links to other pages that further explain the term. Enjoy. Woodworking Glossary A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | #'s | A | A-Frame This is a common and strong building and construction shape where you place two side pieces in the orientation of the legs of a letter "A" shape, and then cross brace the middle. This is useful on project ends, and bases where strength is needed. Abrasive Abrasive is a term use to describe sandpaper typically. This is a material that grinds or abrades material, most commonly wood, to change the surface texture. Using Abrasive papers means using sandpaper in most cases, and you can use it on wood, or on a finish in between coats or for leveling. Absolute Humidity The absolute humidity of the air is a measurement of the amount of water that is in the air. This is without regard to the temperature, and is a measure of how much water vapor is being held in the surrounding air. Acetone Acetone is a solvent that you can use to clean parts, or remove grease. Acetone is useful for removing and cutting grease on a wooden bench top that has become contaminated with oil. Across the Grain When looking at the grain of a piece of wood, if you were to scratch the piece perpendicular to the direction of the grain, this would be an across the grain scratch. -

7 DIY Caning Projects That Let You Try the Trendy Woven Technique at Home | Better Homes & Gardens

8/14/2020 7 DIY Caning Projects That Let You Try the Trendy Woven Technique at Home | Better Homes & Gardens 7 DIY Caning Projects That Let You Try the Trendy Woven Technique at Home Cane furniture, a design trend that dates to ancient Egypt, is having a 21st-century moment. Here's how to bring it home in ways big and small. By Lacey Howard , Jessica Bennett and Jeni Wright August 05, 2020 Each product we feature has been independently selected and reviewed by our editorial team. If you make a purchase using the links included, we may earn commission. Although it has historical roots, caning is one of our favorite home trends of the moment. Created using thin rattan strips, the multi-directional woven pattern brings natural texture and timeless style to all types of furnishings. To try this weaving technique yourself, you'll need to purchase strands of rattan called binding cane ($14, Amazon). For a shortcut, you can also find rolls of pre-woven cane webbing ($9, Micheals) online and at fabric stores. Once you have your supplies, check out these clever DIY caning projects to create your own furniture and decor using the woven treatment. DIY Cane Headboard Three panels team up to create a cane headboard for a full-size bed (you can scale up the size of each panel for a larger bed). When you weave your own panels, you have total artistic control over the pattern and size of the weave. For instant gratification, shop for pre-woven caning material. To complete the look, we added a floating shelf above the headboard and outfitted it with plants. -

212.6-1738.Pdf

212.61738 AOVIESBUREAU VOOR WATERVOORZIENING IWACO B.V. INTERNATIONAL WATER SUPPLY CONSULTANTS L d~z~-~ With compliments IWACO BV Telephone 010-143622 P0 Box 183 Telex 24069n1 3000 AD Rotterdam Cables IWACO Rotterdam The Netherlands Office Schiekade 189, Rotterdam ~ -L ~ 3 r-,!-, ~t~:1~I S I~i Table of contents. Page: ~. Introduction. 1 Aquifer and well losses~condition of the well. 2 I 2.12. Different types of losses. 2 Determination of well losses. 3 I 2.32.2 Step—drawdown tests, interpretation of the resultJ. 6 Causes of clogging of wells. 12 1~3.1 Mechanical clogging. 12 Chemical clogging. 13 13.23.2.1 Carbonate incrustation. 13 15 13.2.2 Iron—and manganese oxidation. 3.3 Clogging due to bacteriological activity. i6 Iron-and manganese oxidising bacteria. 16 I 3.3.~ 3.3.2 Sulphate reducing bacteria. 17 ~ Clogging of screens due to return flow of water. 18 3.5 Clogging due to sand entrance. 18 14 Well construction. 23 4.1 Present method of well construction. • 23 14.2 Drilling methods. 25 Hydraulic rotary drilling with reverse 25 I 4.2.1 , circulation. ‘4.2.2 Hydraulic rotary drilling with 26 straight circulation. Manual waterjet/rotary drilling with 27 ~42.3 temporary casing. Well construction related to the longevity of 28 r.3 the well. Well screen and gravelpack. 28 • I4.3.2 Well screen and well casing material 1 related to chemical attack. 4.3.3 Strength of the well. 30 1~3 • 4 Provisions for monitoring. 33 4.3.5 Remaining aspects. I 33 Lr/~’( ~ 1 I — I I I -1-- Page 5. -

50 Years 1967-2017 a Message from Our President About Chesapeake Center, Inc

Watercolor by Joan McGarry 50 YEARS 1967-2017 A MESSAGE FROM OUR PRESIDENT ABOUT CHESAPEAKE CENTER, INC. How exciting to be involved with a successful nonprofit that has been in Chesapeake Center, Inc. is a private, non-profit service provider for business for 50 years! This occasion is very humbling for me when I think adults with disabilities, celebrating 50 years of continuous operation in back to the initial position I held with the Chesapeake Center in 1981 as Easton, Maryland. Chesapeake Center has evolved over the years as a a Live-in House Counselor! It has been so fulfilling to work for the same comprehensive system of services designed to assist adult individuals company for 36 years in various roles along the road to the Center’s with disabilities to reach their potential for independence by pursuing success. Supports and services for adults with various disabilities have opportunities in housing, employment, transportation, natural changed since the Chesapeake Center’s meager beginnings in 1967. supports, friendships and community activities. Their mission is to Thanks to Mrs. W. Alton Jones and her foresight in helping many Talbot promote independence and an integrated life through interaction and County agencies get off the ground, and the dedication of family and association with other individuals and groups in the local community. community members, the Chesapeake Center Inc. is proud to be a major employer, a large Talbot County land owner and a successful nonprofit business. The Chesapeake Center’s vision is to realize a caring community in which adults with disabilities become empowered to demonstrate their choice of residence, career, friends and activities where they are safe from abuse, neglect, recrimination and ridicule. -

Wood Magazine 95

HALF-BLIND DOVETAILS 9 steps to sure success Page 42 Better Homes and Gardens «tY/»M»lY ORKING MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1997 ISSUE NO. 95 P FENCE ROUNDUP WE TEST 21 MODELS Page 53 ' MUST-BUILD Country buffet •Circle-top shel n IH I i L*l*l III [•IHfJ MM Bandsawn box^_^ I Turned pocket watch ~~~~ Kid's stilts ^— Cockatoo bank 02> w "92567"U072 Please display until February 11 The New Force of Grizzly! Both Come With A Carbide-Tipped Saw Blade! • ^ ,S0gJ !j-J W2M INTRODUCTORY PRICE INTRODUCTORY PRICE $ 00 $109500 j! 449 I tools. The Z-SER1ES represents top of the We are proud to introduce our Z-SERIES line of woodworking sought after features in a tablesaw and line" versions of our standard table saws. We've taken the most contractor or cabinet-style incorporated them into the best saws you can find. So, whether you are after the call- won't be disappointed! tablesaw, you owe it to yourself to give us a you G1022Z G1023Z • Front rail-mounted magnetic Belt driven from the rear-mounted motor to the arbor switch for easy access 4" - with dust port and clean-out Heavy-duty rip fence IMPORTS, INC. micro-adjustment knob • SHOP FOX* Fence Quick-lock fence locks front and back New saw guard All ball bearing mechanism Purveyors of • Beveled table edge Beveled table edge Fine Machinery. Motor Cover • H.P. Single Phase, 11 0/2 20V motor Vh • T miter slots Sturdy stand 3 H.P., 220V motor Precision-ground cast iron table • Triple V-belt drive and extensions • Shipping weight: approx.