Smarter Together Why Artificial Intelligence Needs Human-Centered Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Version

Deloitte Perspective Deloitte Can the Punch Bowl Really Be Taken Away? The Future of Shared Mobility in China Perspective Gradual Reform Across the Value Chain 2018 (Volume VII) 2018 (Volume VII) 2018 (Volume About Deloitte Global Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a UK private company limited by guarantee (“DTTL”), its network of member firms, and their related entities. DTTL and each of its member firms are legally separate and independent entities. DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) does not provide services to clients. Please see www.deloitte.com/about to learn more about our global network of member firms. Deloitte provides audit & assurance, consulting, financial advisory, risk advisory, tax and related services to public and private clients spanning multiple industries. Deloitte serves nearly 80 percent of the Fortune Global 500® companies through a globally connected network of member firms in more than 150 countries and territories bringing world-class capabilities, insights, and high-quality service to address clients’ most complex business challenges. To learn more about how Deloitte’s approximately 263,900 professionals make an impact that matters, please connect with us on Facebook, LinkedIn, or Twitter. About Deloitte China The Deloitte brand first came to China in 1917 when a Deloitte office was opened in Shanghai. Now the Deloitte China network of firms, backed by the global Deloitte network, deliver a full range of audit & assurance, consulting, financial advisory, risk advisory and tax services to local, multinational and growth enterprise clients in China. We have considerable experience in China and have been a significant contributor to the development of China's accounting standards, taxation system and local professional accountants. -

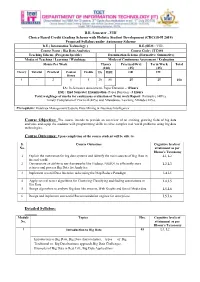

(CBCGS-H 2019) Proposed Syllabus Under Autonomy Scheme

B.E. Semester –VIII Choice Based Credit Grading Scheme with Holistic Student Development (CBCGS-H 2019) Proposed Syllabus under Autonomy Scheme B.E.( Information Technology ) B.E.(SEM : VIII) Course Name : Big Data Analytics Course Code : ITC801 Teaching Scheme (Program Specific) Examination Scheme (Formative/ Summative) Modes of Teaching / Learning / Weightage Modes of Continuous Assessment / Evaluation Hours Per Week Theory Practical/Oral Term Work Total (100) (25) (25) Theory Tutorial Practical Contact Credits IA ESE OR TW Hours 4 - 2 6 5 20 80 25 25 150 IA: In-Semester Assessment- Paper Duration – 1Hours ESE : End Semester Examination- Paper Duration - 3 Hours Total weightage of marks for continuous evaluation of Term work/Report: Formative (40%), Timely Completion of Practical (40%) and Attendance /Learning Attitude (20%). Prerequisite: Database Management System, Data Mining & Business Intelligence Course Objective: The course intends to provide an overview of an exciting growing field of big data analytics and equip the students with programming skills to solve complex real world problems using big data technologies. Course Outcomes: Upon completion of the course student will be able to: S. Course Outcomes Cognitive levels of No. attainment as per Bloom’s Taxonomy 1 Explain the motivation for big data systems and identify the main sources of Big Data in L1, L2 the real world. 2 Demonstrate an ability to use frameworks like Hadoop, NOSQL to efficiently store L2,L3 retrieve and process Big Data for Analytics. 3 Implement several Data Intensive tasks using the Map Reduce Paradigm L4,L5 4 Apply several newer algorithms for Clustering Classifying and finding associations in L4,L5 Big Data 5 Design algorithms to analyze Big data like streams, Web Graphs and Social Media data. -

Redefine Work: the Untapped Opportunity for Expanding Value

A report from the Deloitte Center for the Edge Redefine work The untapped opportunity for expanding value Deloitte Consulting LLP’s Human Capital practice focuses on optimizing and sustaining organiza- tional performance through their most important asset: their workforce. We do this by advising our clients on a core set of issues including: how to successfully navigate the transition to the future of work; how to create the “simply irresistible” experience; how to activate the digital orga- nization by instilling a digital mindset—and optimizing their human capital balance sheet, often the largest part of the overall P&L. The practice’s work centers on transforming the organization, workforce, and HR function through a comprehensive set of services, products, and world-class Bersin research enabled by our proprietary Human Capital Platform. The untapped opportunity for expanding value Contents Introduction: Opportunity awaits—down a different path | 2 A broader view of value | 4 Redefining work everywhere: What does the future of human work look like? | 6 Breaking from routine: Work that draws on human capabilities | 11 Focusing on value for others | 18 Making work context-specific | 21 Giving and exercising latitude | 25 How do we get started? | 31 Endnotes | 34 1 Redefine work Introduction: Opportunity awaits—down a different path Underneath the understandable anxiety about the future of work lies a significant missed opportunity. That opportunity is to return to the most basic question of all: What is work? If we come up with a creative answer to that, we have the potential to create significant new value for the enterprise. -

Design for Use

Research-Technology Management ISSN: 0895-6308 (Print) 1930-0166 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/urtm20 Design for Use Don Norman & Jim Euchner To cite this article: Don Norman & Jim Euchner (2016) Design for Use, Research-Technology Management, 59:1, 15-20 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08956308.2016.1117315 Published online: 08 Jan 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=urtm20 Download by: [Donald Norman] Date: 10 January 2016, At: 13:57 CONVERSATIONS Design for Use An Interview with Don Norman Don Norman talks with Jim Euchner about the design of useful things, from everyday objects to autonomous vehicles. Don Norman and Jim Euchner Don Norman has studied everything from refrigerator the people we’re designing for not only don’t know about thermostats to autonomous vehicles. In the process, he all of these nuances; they don’t care. They don’t care how has derived a set of principles that govern what makes much effort we put into it, or the kind of choices we made, designed objects usable. In this interview, he discusses some or the wonderful technology behind it all. They simply care of those principles, how design can be effectively integrated that it makes their lives better. This requires us to do a into technical organizations, and how designers can work design quite differently than has traditionally been the case. as part of product development teams. -

Malcolm Mccullough

G R Malcolm McCullough Architecture, Pervasive Computing, and Environmental Knowing The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Universal Situated Anytime-anyplace Responsive place Mostly portable Mostly embedded Ad hoc aggregation Accumulated aggregation Context is location Context is activity Instead of architecture Inside of architecture Fast and far Slow and closer Uniform Adapted 4.1 Universal versus situated computing When everyday objects boot up and link, more of us need to under stand technology well enough to take positions about its design. What are the essential components, and what are the contextual design Embedded G ear implications of the components? How do the expectations we have 4 examined influence the design practices we want to adapt? As a point of departure, and with due restraint on the future tense, it is worth looking at technology in itself. To begin, consider how not all ubiquitous computing is portable computing. As a contrast to the universal mobility that has been the focus of so much attention, note the components of digital systems that are embedded in physical sites (figure 4.1). "Embedded" means enclosed; these chips and software are not considered computers. They are unseen parts of everyday things. "The most profound tech nologies are those that disappear," was Mark Weiser's often-repeated dictum. "They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it." 1 Bashing the Desktop Some general background on the state of the computer industry is nec essary first, particularly regarding the all-too-familiar desktop com puter. By the beginning of the new century, technologists commonly asserted that a computer interface need not involve a keyboard, mouse, and screen. -

Designing for the Internet of Things a Curated Collection of Chapters from the O’Reilly Design Library

DOWNLOADFREE Designing for the Internet of Things A Curated Collection of Chapters from the O’Reilly Design Library Software Above Designing the Level of Understanding Connected a Single Device Industrial Products The Implications Design UX FOR THE CONSUMER PRINCIPLES FOR UX AND INTERNET OF THINGS INTERACTION DESIGN Claire Rowland, Elizabeth Goodman, Tim O’Reilly Martin Charlier, Alfred Lui & Ann Light Simon King & Kuen Chang Discussing Design IMPROVING COMMUNICATION & COLLABORATION THROUGH CRITIQUE Adam Connor & Aaron Irizarry Designing for the Internet of Things A Curated Collection of Chapters from the O'Reilly Design Library Learning the latest methodologies, tools, and techniques is critical for IoT design, whether you’re involved in environmental monitoring, building automation, industrial equipment, remote health monitoring devices, or an array of other IoT applications. The O’Reilly Design Library provides experienced designers with the knowledge and guidance you need to build your skillset and stay current with the latest trends. This free ebook gets you started. With a collection of chapters from the library’s published and forthcoming books, you’ll learn about the scope and challenges that await you in the burgeoning IoT world, as well as the methods and mindset you need to adopt. The ebook includes excerpts from the following books. For more information on current and forthcoming Design content, check out www.oreilly.com/design Mary Treseler Strategic Content Lead [email protected] Designing for Emerging Technologies Available now: http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920030676.do Chapter 5. Learning and Thinking with Things Chapter 13. Architecture as Interface Chapter 14. Design for the Networked World Designing Connected Products Available in Early Release: http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920031109.do Chapter 4. -

Prototyping User Experiences

Sketching with Hardware photo credits © alexander wiethoff basic stamp bx 24 basic atom pic higher level lower level Assembly Atmel AT Mega 328 Raspberry PI http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3d/RaspberryPi.jpg http://www.onlymine.de/wp-content/uploads/arduino-nano-board-z.jpg Thermistor Bend Sensor PIR Sensor photo credits © wikimedia Force Sensor Potentiometer Magnet Switch photo credits © wikimedia Distance IR Sensor Touch QT Sensor Ultrasound Sensor photo credits © wikimedia photo credits © alexander wiethoff photo credits © alexander wiethoff Some Examples from a school called Copenhagen Institute of Interaction Design (CIID) Some Examples from a school called Copenhagen Institute of Interaction Design (CIID) 2 Weeks 2 Weeks Phase 1 Field Research Desk Research User Research Phase 2 Concepts Analysis and Concept Generation Phase 3 Prototyping Prototyping Phase 4 LO Fidelity HI Fidelity Usability Testing Phase 5 Final Prototype Implementation ;GH=F@9?=F IDII CASES 66 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F IDII CASES 67 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F IDII CASES 68 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F IDII CASES 69 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F IDII CASES 70 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F IDII CASES 71 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F IDII CASES 72 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F IDII CASES 73 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F IDII CASES 74 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F IDII CASES 75 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F CASES 76 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F CASES 77 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F CASES 78 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F CASES 79 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F CASES 80 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F ;GH=F@9?=F CASES 81 AFKLALML= G> AFL=J9;LAGF <=KA?F Thanks for your attention ! Tutorials Physical Computing Intro https://itp.nyu.edu/physcomp/ Arduino Tutorials https://www.arduino.cc/en/Tutorial/HomePage Physical Computing w. -

Is There a Future for Human Factors in the 21St Century?

Is There a Future for Human Factors in the 21st Century? A Keynote Address at the NATO RTA Specialist Meeting “Human Factors in the 21st Century” (June 2001) Nahum Gershon1 The MITRE Corporation 1820 Dolley Madison Blvd. McLean, VA 22102 [email protected] “…The development of Mosaic/Netscape is a good example of the value of Human Factors. We should use it to convince our high level management that they should invest more funds in this area…” A distinguished Speaker, 1996 I was quite surprised to hear this declaration at a Human Factors meeting a few years ago. After all, Mosaic was developed by undergraduate students who might never have heard the term “human factors”. This made me ponder why did the distinguished speaker not find better recent examples developed by the Human Factors community instead of resorting to a development not made by this community? How could such a breakthrough in human computer interaction (and human information interaction- HII) be developed without the help of the Human Factors community? Could the Human Factors community in its present form design and develop such a visionary interface? In the rest of this paper, I would like to dwell on some of the related but crucial questions and challenges facing the Human Factors community. To my mind, the issues are straightforward. Measurements and usability testing have been the cornerstone of our profession. The achievement list of Human factors is quite long (in areas including, for example, information displays and other sensory level systems, refining the computer mouse, and the desktop metaphor). However, in the process of doing our work, we have lost some of our vision. -

BEYOND DESIGN ETHNOGRAPHY Nicolas Nova

BEYOND DESIGN ETHNOGRAPHY Nicolas Nova To cite this version: Nicolas Nova. BEYOND DESIGN ETHNOGRAPHY: How Designers Practice Ethnographic Re- search. France. SHS Publishing, 2014, 978-8-89-075944-4. halshs-01514264 HAL Id: halshs-01514264 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01514264 Submitted on 27 Apr 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License BEYOND DESIGN ETHNOGRAPHY HOW DESIGNERS PRACTICE ETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH Edited by Nicolas Nova BEYOND DESIGN ETHNOGRAPHY CONTENT PREFACE 4 FOREWORD 7 USERS IN DESIGN 11 DESIGN ETHNOGRAPHY? 29 FIELD RESEARCH & DESIGN 45 PERSONAL STANCES 69 CASE STUDIES 83 CONCLUSION 117 APPROACH 120 LEXICON 123 BIBLIOGRAPHY 128 2 BEYOND DESIGN ETHNOGRAPHY HEAD – Genève (Geneva University of Art and Design) is proud to present its publication Beyond Design Ethnography: How Designers Practice Ethnography Research edited by Nicolas Nova, Professor within the Masters program in Media Design. Although discourse on the origins of design varies according to the different historiographical approaches, it is clear that for several decades now the design research community has been gradually setting out its own markers in the establishment of a scientific discipline. -

COMM 339 Communication Technology and Culture Spring 2012

COMM 339: Communication Technology and Culture Syllabus COMM 339 Communication Technology and Culture Spring 2012 Professor: Douglas Thomas Time: Wednesdays, 2:00 – 4:50 Phone: 213-743-1939 Location: Kerckhoff Hall (KER) 101 Email: [email protected] 734 W. Adams Boulevard Office Hours: By appointment Section: 20540R Credits: 4 Professor: Susan Metros Blackboard Course Site: https://blackboard.usc.edu Phone: 213-821-8084 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: By appointment Course Description This course is designed to explore the intersections of technology, culture, and imagination. As an industry, a site of cultural production, and a factor in our everyday lives, technology has had the power to change everything about the way we live, see the world, and engage in every facet of human communication. This course is designed to explore one of the pathways through which that happens-- imagination. Course Objective The primary objectives of this course are threefold: to understand where ideas come from, to learn how to implement ideas (turn ideas into actions), and to engage in assessment of those ideas. Learning Outcomes By the completion of this course, students will know how to apply creative problem solving processes for the purpose of analyzing, selecting, implementing, and evaluating ideas. They will have practiced the basic tenets of design, taking a topic that has personal interest to them and creating a project summary and work plan that will allow them to “follow their passion” from inception to execution to assessment of their original idea for utilizing or engaging communication technology. They also will be able to describe (pitch) their idea verbally, textually, and visually to a variety of diverse audiences. -

Programming Interactivity.Pdf

Download at Boykma.Com Programming Interactivity A Designer’s Guide to Processing, Arduino, and openFrameworks Joshua Noble Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo Download at Boykma.Com Programming Interactivity by Joshua Noble Copyright © 2009 Joshua Noble. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://my.safaribooksonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: (800) 998-9938 or [email protected]. Editor: Steve Weiss Indexer: Ellen Troutman Zaig Production Editor: Sumita Mukherji Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery Copyeditor: Kim Wimpsett Interior Designer: David Futato Proofreader: Sumita Mukherji Illustrator: Robert Romano Production Services: Newgen Printing History: July 2009: First Edition. Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O’Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Programming Interactivity, the image of guinea fowl, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O’Reilly Media, Inc., was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information con- tained herein. TM This book uses RepKover™, a durable and flexible lay-flat binding. -

Rethinking Technology Neutrality Brad A

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 2016 Rethinking Technology Neutrality Brad A. Greenberg Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Greenberg, Brad A., "Rethinking Technology Neutrality" (2016). Minnesota Law Review. 207. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/207 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Article Rethinking Technology Neutrality Brad A. Greenberg† INTRODUCTION Should laws be technology specific or technology neutral? That is, should laws be drawn narrowly to specific technologies or broadly to general characteristics? Scholars and legislators have overwhelmingly adopted the latter mode—“technology neutrality”—based on the assumption it promotes statutory longevity and equal treatment of old and new technologies. But technology neutrality suffers from inherent flaws that under- mine its ability to achieve these policy goals. Neutrality, it turns out, is both suboptimal and often self-defeating. It is also not neutral. Four fraught decades in copyright law, during which tech- nology neutrality was supposed to mitigate a perennial struggle of adapting copyright to new communications technologies, re- veal fundamental failings. With the 1976 Copyright Act,1 a Congress weary of recurring demands to revise copyright law in light of new technologies—e.g., phonographs, film, radio, cable † Visiting Fellow, Information Society Project, Yale Law School; Coun- sel, U.S. Copyright Office.