Calm Technology in Museums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Version

Deloitte Perspective Deloitte Can the Punch Bowl Really Be Taken Away? The Future of Shared Mobility in China Perspective Gradual Reform Across the Value Chain 2018 (Volume VII) 2018 (Volume VII) 2018 (Volume About Deloitte Global Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a UK private company limited by guarantee (“DTTL”), its network of member firms, and their related entities. DTTL and each of its member firms are legally separate and independent entities. DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) does not provide services to clients. Please see www.deloitte.com/about to learn more about our global network of member firms. Deloitte provides audit & assurance, consulting, financial advisory, risk advisory, tax and related services to public and private clients spanning multiple industries. Deloitte serves nearly 80 percent of the Fortune Global 500® companies through a globally connected network of member firms in more than 150 countries and territories bringing world-class capabilities, insights, and high-quality service to address clients’ most complex business challenges. To learn more about how Deloitte’s approximately 263,900 professionals make an impact that matters, please connect with us on Facebook, LinkedIn, or Twitter. About Deloitte China The Deloitte brand first came to China in 1917 when a Deloitte office was opened in Shanghai. Now the Deloitte China network of firms, backed by the global Deloitte network, deliver a full range of audit & assurance, consulting, financial advisory, risk advisory and tax services to local, multinational and growth enterprise clients in China. We have considerable experience in China and have been a significant contributor to the development of China's accounting standards, taxation system and local professional accountants. -

(CBCGS-H 2019) Proposed Syllabus Under Autonomy Scheme

B.E. Semester –VIII Choice Based Credit Grading Scheme with Holistic Student Development (CBCGS-H 2019) Proposed Syllabus under Autonomy Scheme B.E.( Information Technology ) B.E.(SEM : VIII) Course Name : Big Data Analytics Course Code : ITC801 Teaching Scheme (Program Specific) Examination Scheme (Formative/ Summative) Modes of Teaching / Learning / Weightage Modes of Continuous Assessment / Evaluation Hours Per Week Theory Practical/Oral Term Work Total (100) (25) (25) Theory Tutorial Practical Contact Credits IA ESE OR TW Hours 4 - 2 6 5 20 80 25 25 150 IA: In-Semester Assessment- Paper Duration – 1Hours ESE : End Semester Examination- Paper Duration - 3 Hours Total weightage of marks for continuous evaluation of Term work/Report: Formative (40%), Timely Completion of Practical (40%) and Attendance /Learning Attitude (20%). Prerequisite: Database Management System, Data Mining & Business Intelligence Course Objective: The course intends to provide an overview of an exciting growing field of big data analytics and equip the students with programming skills to solve complex real world problems using big data technologies. Course Outcomes: Upon completion of the course student will be able to: S. Course Outcomes Cognitive levels of No. attainment as per Bloom’s Taxonomy 1 Explain the motivation for big data systems and identify the main sources of Big Data in L1, L2 the real world. 2 Demonstrate an ability to use frameworks like Hadoop, NOSQL to efficiently store L2,L3 retrieve and process Big Data for Analytics. 3 Implement several Data Intensive tasks using the Map Reduce Paradigm L4,L5 4 Apply several newer algorithms for Clustering Classifying and finding associations in L4,L5 Big Data 5 Design algorithms to analyze Big data like streams, Web Graphs and Social Media data. -

Solving Human Centric Challenges in Ambient Intelligence Environments to Meet Societal Needs

Solving Human Centric Challenges in Ambient Intelligence Environments to Meet Societal Needs A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the School of Engineering and Applied Science University of Virginia In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy (Computer Science) by Erin Griffiths December 2019 © 2019 Erin Griffiths Approval Sheet This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Computer Science) Erin Griffiths This dissertation has been read and approved by the Examining Committee: Kamin Whitehouse, Adviser Jack Stankovic, Committee Chair Mary Lou Soffa A.J. Brush John Lach Accepted for the School of Engineering and Applied Science: Dean, School of Engineering and Applied Science December 2019 i To everyone who has helped me along the way. ii Abstract In the world today there exists a large number of problems that are of great societal concern, but suffer from a problem called the tragedy of the commons where there isn`t enough individual incentive for people to change their behavior to benefit the whole. One of the biggest examples of this is in energy consumption where research has shown that we can reduce 20-50% of the energy used in buildings if people would consistently modify their behavior. However, consistent behavior modification to meet societal goals that are often low priority on a personal level is often prohibitively difficult in the long term. Even systems design to assist in meeting these needs may be unused or disabled if they require too much effort, infringe on privacy, or are frustratingly inaccurate. -

Redefine Work: the Untapped Opportunity for Expanding Value

A report from the Deloitte Center for the Edge Redefine work The untapped opportunity for expanding value Deloitte Consulting LLP’s Human Capital practice focuses on optimizing and sustaining organiza- tional performance through their most important asset: their workforce. We do this by advising our clients on a core set of issues including: how to successfully navigate the transition to the future of work; how to create the “simply irresistible” experience; how to activate the digital orga- nization by instilling a digital mindset—and optimizing their human capital balance sheet, often the largest part of the overall P&L. The practice’s work centers on transforming the organization, workforce, and HR function through a comprehensive set of services, products, and world-class Bersin research enabled by our proprietary Human Capital Platform. The untapped opportunity for expanding value Contents Introduction: Opportunity awaits—down a different path | 2 A broader view of value | 4 Redefining work everywhere: What does the future of human work look like? | 6 Breaking from routine: Work that draws on human capabilities | 11 Focusing on value for others | 18 Making work context-specific | 21 Giving and exercising latitude | 25 How do we get started? | 31 Endnotes | 34 1 Redefine work Introduction: Opportunity awaits—down a different path Underneath the understandable anxiety about the future of work lies a significant missed opportunity. That opportunity is to return to the most basic question of all: What is work? If we come up with a creative answer to that, we have the potential to create significant new value for the enterprise. -

Ambient Intelligence

Ambient intelligence Ambient intelligence is closely related to the long term vision of an intelligent service system in which technolo- gies are able to automate a platform embedding the re- quired devices for powering context aware, personalized, adaptive and anticipatory services. Where in other me- dia environment the interface is clearly distinct, in an ubiquitous environment 'content' differs. Artur Lugmayr defined such a smart environment by describing it as ambient media. It is constituted of the communication of information in ubiquitous and pervasive environments. The concept of ambient media relates to ambient media form, ambient media content, and ambient media tech- nology. Its principles have been established by Artur Lug- mayr and are manifestation, morphing, intelligence, and experience.[1][2] An (expected) evolution of computing from 1960–2010. A typical context of ambient intelligence environment is In computing, ambient intelligence (AmI) refers to a Home environment (Bieliková & Krajcovic 2001). electronic environments that are sensitive and respon- sive to the presence of people. Ambient intelligence is a vision on the future of consumer electronics, 1 Overview telecommunications and computing that was originally developed in the late 1990s for the time frame 2010– 2020. In an ambient intelligence world, devices work in More and more people make decisions based on the effect concert to support people in carrying out their everyday their actions will have on their own inner, mental world. life activities, tasks and rituals in an easy, natural way us- This experience-driven way of acting is a change from ing information and intelligence that is hidden in the net- the past when people were primarily concerned about the work connecting these devices (see Internet of Things). -

Design for Use

Research-Technology Management ISSN: 0895-6308 (Print) 1930-0166 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/urtm20 Design for Use Don Norman & Jim Euchner To cite this article: Don Norman & Jim Euchner (2016) Design for Use, Research-Technology Management, 59:1, 15-20 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08956308.2016.1117315 Published online: 08 Jan 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=urtm20 Download by: [Donald Norman] Date: 10 January 2016, At: 13:57 CONVERSATIONS Design for Use An Interview with Don Norman Don Norman talks with Jim Euchner about the design of useful things, from everyday objects to autonomous vehicles. Don Norman and Jim Euchner Don Norman has studied everything from refrigerator the people we’re designing for not only don’t know about thermostats to autonomous vehicles. In the process, he all of these nuances; they don’t care. They don’t care how has derived a set of principles that govern what makes much effort we put into it, or the kind of choices we made, designed objects usable. In this interview, he discusses some or the wonderful technology behind it all. They simply care of those principles, how design can be effectively integrated that it makes their lives better. This requires us to do a into technical organizations, and how designers can work design quite differently than has traditionally been the case. as part of product development teams. -

A. Define and Explain the Internet of Things

IoT Solutions 1. Attempt any three of the following: a. Define and explain the Internet of Things. Ans: The Internet of things is defined as a paradigm in which objects equipped with sensors, actuators, and processors communicate with each other to serve a meaningful purpose. Equation of Internet of Things: Physical Object + Controllers, Sensors and Actuators + Internet = Internet of Things Physical Object: Devices, vehicles, buildings and other items which are embedded with electronics, software, sensors, and network connectivity, which enables these objects to collect and exchange data. Controllers: A controller, in a computing context, is a hardware device or a software program that manages or directs the flow of data between two entities In a general sense, a controller can be thought of as something or someone that interfaces between two systems and manages communications between them. Sensors: Sensor is a device, module, or subsystem whose purpose is to detect events or changes in its environment and send the information to other electronics, frequently a computer processor. A sensor is always used with other electronics. Actuators: An actuator is a component of a machine that is responsible for moving and controlling a mechanism or system. Internet: The internet is a globally connected network system that uses TCP/IP to transmit data via various types of media. The internet is a network of global exchanges – including private, public, business, academic and government networks – connected by guided, wireless and fiber-optic technologies. Example of Internet of Things: In your kitchen, a blinking light reminds you it’s time to take your tablets. -

Core Concept: the Internet of Things and the Explosion of Interconnectivity

CORE CONCEPTS The Internet of Things and the explosion of interconnectivity CORE CONCEPTS Stephen Ornes, Science Writer It was 1982, and a group of computer science graduate students at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was thirsty for more than knowledge: some wanted a Coca Cola. But the researchers were frustrated. The Coke machine was on the third floor of the university’s Wean Hall, and oftentimes they’d venture up to the dis- penser only to find it empty, or worse, full of warm soda. So the scientists connected the machine to the university’s computer network. By checking online, thirsty researchers could ensure the machine was stocked with cold bottles before visiting. This turned out to be more than an achieve- ment in efficient caffeine delivery; it’s thought to be one of the first noncomputer objects to go online (1). The notion of pervasive computing entails a vision of the world in which computing isn’t limited to tab- lets, smartphones, and laptops. The realization of this vision, called the “Internet of Things” (IoT), is the ever- expanding collection of connected devices that cap- ture and share data. Any object, outfitted with the right Pervasive computing and its realization, known as the “Internet of Things,” entails sensors, can observe and interact with its environment. an ever-expanding collection of connected devices that capture and share data. A homeowner can adjust the thermostat, close the Image courtesy of Shutterstock/a-image. blinds, or raise a garage door with a voice command to a smartphone app. A connected refrigerator can send a list of its inventory to a shopper. -

Ubiquitous Computing Research at PARC in the Late 1980S

The origins of ubiquitous computing research at PARC in the late 1980s by M. Weiser R. Gold † J. S. Brown ‡ Ubiquitous computing began in the Electronics At the same time, the anthropologists of the Work and Imaging Laboratory of the Xerox Palo Alto Practices and Technology area within PARC, led by Research Center. This essay tells the inside story of its evolution from “computer walls” to “calm Lucy Suchman, were observing the way people re- computing.” ally used technology, not just the way they claimed to use technology. To some of the technologists at PARC, myself included, their observations led toward thinking less about particular features of a comput- er—such as random access memory and number of pixels or megahertz—and much more about the de- n late 1987, Bob Sprague, Richard Bruce, and tailed situational use of the technology. In partic- other members of the Xerox Palo Alto Research I ular, how were computers embedded within the com- Center (PARC) Electronics and Imaging Laboratory plex social framework of daily activity, and how did (EIL) proposed fabricating large, wall-sized, flat- they interplay with the rest of our densely woven panel computer displays from large-area amorphous physical environment (also known as “the real silicon sheets. It was thought at the time that this world”)? technology might also permit these displays to func- tion as input devices for electronic pens and also for From these converging forces (“from atoms to cul- the scanning of images (by placing documents di- ture,” as we like to say of PARC) emerged the Ubiq- rectly against the displays). -

Malcolm Mccullough

G R Malcolm McCullough Architecture, Pervasive Computing, and Environmental Knowing The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Universal Situated Anytime-anyplace Responsive place Mostly portable Mostly embedded Ad hoc aggregation Accumulated aggregation Context is location Context is activity Instead of architecture Inside of architecture Fast and far Slow and closer Uniform Adapted 4.1 Universal versus situated computing When everyday objects boot up and link, more of us need to under stand technology well enough to take positions about its design. What are the essential components, and what are the contextual design Embedded G ear implications of the components? How do the expectations we have 4 examined influence the design practices we want to adapt? As a point of departure, and with due restraint on the future tense, it is worth looking at technology in itself. To begin, consider how not all ubiquitous computing is portable computing. As a contrast to the universal mobility that has been the focus of so much attention, note the components of digital systems that are embedded in physical sites (figure 4.1). "Embedded" means enclosed; these chips and software are not considered computers. They are unseen parts of everyday things. "The most profound tech nologies are those that disappear," was Mark Weiser's often-repeated dictum. "They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it." 1 Bashing the Desktop Some general background on the state of the computer industry is nec essary first, particularly regarding the all-too-familiar desktop com puter. By the beginning of the new century, technologists commonly asserted that a computer interface need not involve a keyboard, mouse, and screen. -

Designing for the Internet of Things a Curated Collection of Chapters from the O’Reilly Design Library

DOWNLOADFREE Designing for the Internet of Things A Curated Collection of Chapters from the O’Reilly Design Library Software Above Designing the Level of Understanding Connected a Single Device Industrial Products The Implications Design UX FOR THE CONSUMER PRINCIPLES FOR UX AND INTERNET OF THINGS INTERACTION DESIGN Claire Rowland, Elizabeth Goodman, Tim O’Reilly Martin Charlier, Alfred Lui & Ann Light Simon King & Kuen Chang Discussing Design IMPROVING COMMUNICATION & COLLABORATION THROUGH CRITIQUE Adam Connor & Aaron Irizarry Designing for the Internet of Things A Curated Collection of Chapters from the O'Reilly Design Library Learning the latest methodologies, tools, and techniques is critical for IoT design, whether you’re involved in environmental monitoring, building automation, industrial equipment, remote health monitoring devices, or an array of other IoT applications. The O’Reilly Design Library provides experienced designers with the knowledge and guidance you need to build your skillset and stay current with the latest trends. This free ebook gets you started. With a collection of chapters from the library’s published and forthcoming books, you’ll learn about the scope and challenges that await you in the burgeoning IoT world, as well as the methods and mindset you need to adopt. The ebook includes excerpts from the following books. For more information on current and forthcoming Design content, check out www.oreilly.com/design Mary Treseler Strategic Content Lead [email protected] Designing for Emerging Technologies Available now: http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920030676.do Chapter 5. Learning and Thinking with Things Chapter 13. Architecture as Interface Chapter 14. Design for the Networked World Designing Connected Products Available in Early Release: http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920031109.do Chapter 4. -

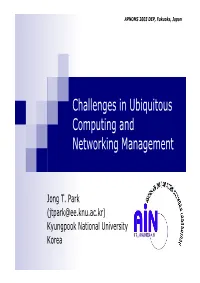

Challenges in Ubiquitous Computing and Networking Management

APNOMS 2003 DEP, Fukuoka, Japan Challenges in Ubiquitous Computing and Networking Management Jong T. Park ([email protected]) Kyungpook National University Korea Ubiquitous Computing & Networking Environment Electronic Cyber Space Smart Real Space Internet Internet Home Network Server (G)MPLS Server Fusion IPv6 Hot Spots 3G/4G Convergence UWB Tiny Invisible Objects Notebook Smart Interface Sensors Web/XML Actuators Bluetooth Multimedia Wearable Handheld Device Computing KNU AIN Lab. APNOMS’2003 2 Features of Cyber Space and Smart Real Space Electronic Cyber Space Smart Real Space Any (time, where, format) Any (device, object)+ Client/Server Computing, P2P Proactive & Embedded (G)MPLS, Broadband Access Computing Network Sensors, MEMS, Wearable B3G/4G, NGN, Post PC, IPv4/v6, Computing, IPv6(+), Near Field XML Communication (UWB, ..) Converging Networks Ad-hoc networks, Home networking Communication/Banking, Comm./(Music/TV Broadcasting), Telematics/Telemetry, e-commerce/government, … u-commerce/government /university/library KNU AIN Lab. APNOMS’2003 3 Current Issues in Ubiquitous Computing and Networking Current Technical Issues Low Power Intelligent Tiny Chip and Sensors Ubiquitous Interface Near-field Communication (UWB, ..), IPv6 Protection of Privacy and Security Management Intelligent Personalization Non-Technical Issues Laws and Regulation Sociological Impact KNU AIN Lab. APNOMS’2003 4 Research Projects America MIT’s Auto-ID and Oxigen, Berkeley’s Smart Dust, NIST’s Smart Space MS’s EasyLiving, HP’s CoolTown Europe