The Parthenon and the Ara Pacis… and Why They Are Both Really Weird an Introduction to Aeneid 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; Proquest Pg

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; ProQuest pg. 387 The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus N. G. L. Hammond TUDENTS of ancient history sometimes fall into the error of read Sing their history backwards. They assume that the features of a fully developed institution were already there in its earliest form. Something similar seems to have happened recently in the study of the early Attic theatre. Thus T. B. L. Webster introduces his excellent list of monuments illustrating tragedy and satyr-play with the following sentences: "Nothing, except the remains of the old Dionysos temple, helps us to envisage the earliest tragic background. The references to the plays of Aeschylus are to the lines of the Loeb edition. I am most grateful to G. S. Kirk, H. D. F. Kitto, D. W. Lucas, F. H. Sandbach, B. A. Sparkes and Homer Thompson for their criticisms, which have contributed greatly to the final form of this article. The students of the Classical Society at Bristol produce a Greek play each year, and on one occasion they combined with the boys of Bristol Grammar School and the Cathedral School to produce Aeschylus' Oresteia; they have made me think about the problems of staging. The following abbreviations are used: AAG: The Athenian Agora, a Guide to the Excavation and Museum! (Athens 1962). ARNon, Conventions: P. D. Arnott, Greek Scenic Conventions in the Fifth Century B.C. (Oxford 1962). BIEBER, History: M. Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theatre2 (Princeton 1961). -

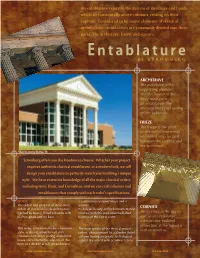

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

Chapter 4, Section 1

Hellenistic Civilization 324 - 100 BC Philip II of Macedonia . The Macedonians were viewed as barbarians. By the 5th century BC, the Macedonians had emerged as a powerful kingdom in the north. In 359 BC, Philip II became king, and he turned Macedonia into the chief power in the Greek world. Philip II Philip II of Macedonia . The Macedonians were viewed as barbarians. By the 5th century BC, the Macedonians had emerged as a powerful kingdom in the north. In 359 BC, Philip II became king, and he turned Macedonia into the chief power in the Greek world. Philip was a great admirer of Greek culture, and he wanted to unite all of Greece under Macedonian rule. Fearing Philip, Athens allied with a number of other Greek city-states to fight the Macedonians. In 338, the Macedonians crushed the Greeks. After quickly gaining control over most of the Greek city-states, Philip turned to Sparta. He sent them a message, "You are advised to submit without further delay, for if I bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people, and raze your city." . Their reply was “if", both Philip and his son, Alexander, would leave the Spartans alone. By 336 BC, Philip was preparing to invade the Persian Empire when he was assassinated. The murder occurred during the celebration of his daughter’s marriage, while the king was entering the theater, he was killed by the captain his bodyguards. Alexander the Great . Alexander III was born in 356 BC. When Alexander was 13, his father Philip chose Aristotle as his tutor, and in return for teaching Alexander, Philip agreed to rebuild Aristotle's hometown which Philip had razed. -

The Conversion of the Parthenon Into a Church: the Tübingen Theosophy

The Conversion of the Parthenon into a Church: The Tübingen Theosophy Cyril MANGO Δελτίον XAE 18 (1995), Περίοδος Δ'• Σελ. 201-203 ΑΘΗΝΑ 1995 Cyril Mango THE CONVERSION OF THE PARTHENON INTO A CHURCH: THE TÜBINGEN THEOSOPHY Iveaders of this journal do not have to be reminded of the sayings "of a certain Hystaspes, king of the Persians the uncertainty that surrounds the conversion of the or the Chaldaeans, a very pious man (as he claims) and for Parthenon into a Christian church. Surprisingly to our that reason deemed worthy of receiving a revelation of eyes, this symbolic event appears to have gone entirely divine mysteries concerning the Saviour's incarnation"5. unrecorded. The only piece of written evidence that has At the end of the work was placed a very brief chronicle been adduced concerns the removal of Athena's cult (perhaps simply a chronology) from Adam to the emperor statue, mentioned without a firm date in Marinus' Life of Zeno (474-91), in which the author advanced the view that Proclus (written in 485/6, the year following the the world would end in the year 6000 from Creation. philosopher's death)1. It is not clear, however, whether The original work was, therefore, composed between this removal marked the conversion of the building to 474 and, at the latest, 508, assuming the author was using Christian worship or merely its desacralization. The two, the Alexandrian computation from 5492 BC. The we have been told, need not have been simultaneous and expectation that the world would end in the reign of it is not inconceivable that the Parthenon remained Anastasius was, indeed, quite widespread at the time6. -

Reading for Monday 4/23/12 History of Rome You Will Find in This Packet

Reading for Monday 4/23/12 A e History of Rome A You will find in this packet three different readings. 1) Augustus’ autobiography. which he had posted for all to read at the end of his life: the Res Gestae (“Deeds Accomplished”). 2) A few passages from Vergil’s Aeneid (the epic telling the story of Aeneas’ escape from Troy and journey West to found Rome. The passages from the Aeneid are A) prophecy of the glory of Rome told by Jupiter to Venus (Aeneas’ mother). B) A depiction of the prophetic scenes engraved on Aeneas’ shield by the god Vulcan. The most important part of this passage to read is the depiction of the Battle of Actium as portrayed on Aeneas’ shield. (I’ve marked the beginning of this bit on your handout). Of course Aeneas has no idea what is pictured because it is a scene from the future... Take a moment to consider how the Battle of Actium is portrayed by Vergil in this scene! C) In this scene, Aeneas goes down to the Underworld to see his father, Anchises, who has died. While there, Aeneas sees the pool of Romans waiting to be born. Anchises speaks and tells Aeneas about all of his descendants, pointing each of them out as they wait in line for their birth. 3) A passage from Horace’s “Song of the New Age”: Carmen Saeculare Important questions to ask yourself: Is this poetry propaganda? What do you take away about how Augustus wanted to be viewed, and what were some of the key themes that the poets keep repeating about Augustus or this new Golden Age? Le’,s The Au,qustan Age 195. -

Domitian's Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome

Rising from the Ashes: Domitian’s Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome Lea K. Cline In the August 1888 edition of the Notizie degli Scavi, profes- on a base of two steps; it is a long, solid rectangle, 6.25 m sors Guliermo Gatti and Rodolfo Lanciani announced the deep, 3.25 m wide, and 1.26 m high (lacking its crown). rediscovery of a Domitianic altar on the Quirinal hill during These dimensions make it the second largest public altar to the construction of the Casa Reale (Figures 1 and 2).1 This survive in the ancient capital. Built of travertine and revet- altar, found in situ on the southeast side of the Alta Semita ted in marble, this altar lacks sculptural decoration. Only its (an important northern thoroughfare) adjacent to the church inscription identifies it as an Ara Incendii Neroniani, an altar of San Andrea al Quirinale, was not unknown to scholars.2 erected in fulfillment of a vow made after the great fire of The site was discovered, but not excavated, in 1644 when Nero (A.D. 64).7 Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini) and Gianlorenzo Bernini Archaeological evidence attests to two other altars, laid the foundations of San Andrea al Quirinale; at that time, bearing identical inscriptions, excavated in the sixteenth the inscription was removed to the Vatican, and then the and seventeenth centuries; the Ara Incendii Neroniani found altar was essentially forgotten.3 Lanciani’s notes from May on the Quirinal was the last of the three to be discovered.8 22, 1889, describe a fairly intact structure—a travertine block Little is known of the two other altars; one, presumably altar with remnants of a marble base molding on two sides.4 found on the Vatican plain, was reportedly used as building Although the altar’s inscription was not in situ, Lanciani refers material for the basilica of St. -

The Athenian Agora

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 12 Prepared by Dorothy Burr Thompson Produced by The Stinehour Press, Lunenburg, Vermont American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1993 ISBN 87661-635-x EXCAVATIONS OF THE ATHENIAN AGORA PICTURE BOOKS I. Pots and Pans of Classical Athens (1959) 2. The Stoa ofAttalos II in Athens (revised 1992) 3. Miniature Sculpturefrom the Athenian Agora (1959) 4. The Athenian Citizen (revised 1987) 5. Ancient Portraitsfrom the Athenian Agora (1963) 6. Amphoras and the Ancient Wine Trade (revised 1979) 7. The Middle Ages in the Athenian Agora (1961) 8. Garden Lore of Ancient Athens (1963) 9. Lampsfrom the Athenian Agora (1964) 10. Inscriptionsfrom the Athenian Agora (1966) I I. Waterworks in the Athenian Agora (1968) 12. An Ancient Shopping Center: The Athenian Agora (revised 1993) I 3. Early Burialsfrom the Agora Cemeteries (I 973) 14. Graffiti in the Athenian Agora (revised 1988) I 5. Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora (1975) 16. The Athenian Agora: A Short Guide (revised 1986) French, German, and Greek editions 17. Socrates in the Agora (1978) 18. Mediaeval and Modern Coins in the Athenian Agora (1978) 19. Gods and Heroes in the Athenian Agora (1980) 20. Bronzeworkers in the Athenian Agora (1982) 21. Ancient Athenian Building Methods (1984) 22. Birds ofthe Athenian Agora (1985) These booklets are obtainable from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens c/o Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J. 08540, U.S.A They are also available in the Agora Museum, Stoa of Attalos, Athens Cover: Slaves carrying a Spitted Cake from Market. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

Agorapicbk-17.Pdf

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 17 Prepared by Mabel L. Lang Dedicated to Eugene Vanderpool o American School of Classical Studies at Athens ISBN 87661-617-1 Produced by the Meriden Gravure Company Meriden, Connecticut COVER: Bone figure of Socrates TITLE PAGE: Hemlock SOCRATES IN THE AGORA AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1978 ‘Everything combines to make our knowledge of Socrates himself a subject of Socratic irony. The only thing we know definitely about him is that we know nothing.’ -L. Brunschvicg As FAR AS we know Socrates himselfwrote nothing, yet not only were his life and words given dramatic attention in his own time in the Clouds of Ar- istophanes, but they have also become the subject of many others’ writing in the centuries since his death. Fourth-century B.C. writers who had first-hand knowledge of him composed either dialogues in which he was the dominant figure (Plato and Aeschines) or memories of his teaching and activities (Xe- nophon). Later authors down even to the present day have written numerous biographies based on these early sources and considering this most protean of philosophers from every possible point of view except perhaps the topograph- ical one which is attempted here. Instead of putting Socrates in the context of 5th-century B.C. philosophy, politics, ethics or rhetoric, we shall look to find him in the material world and physical surroundings of his favorite stamping- grounds, the Athenian Agora. Just as ‘agora’ in its original sense meant ‘gathering place’ but came in time to mean ‘market place’, so the agora itself was originally a gathering place I. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed As the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed as the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon By Brian A. Sprague Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh Western Oregon University Thursday, June 07, 2007 Readers Professor Benedict Lowe Professor Narasingha Sil Copyright © Brian A. Sprague 2007 The Parthenon frieze has been the subject of many debates and the interpretation of it leads to a number of problems: what was the subject of the frieze? What would the frieze have meant to the Athenian audience? The Parthenon scenes have been identified in many different ways: a representation of the Panathenaic festival, a mythical or historical event, or an assertion of Athenian ideology. This paper will examine the Parthenon Frieze in relation to the metopes, pediments, and statues in order to prove the validity of the suggestion that it depicts the Panathenaic festival just preceding the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The main problems with this topic are that there are no primary sources that document what the Frieze was supposed to mean. The scenes are not specific to any one type of procession. The argument against a Panathenaic festival is that there are soldiers and chariots represented. Possibly that biggest problem with interpreting the Frieze is that part of it is missing and it could be that the piece that is missing ties everything together. The Parthenon may have been the only ancient Greek temple with an exterior sculpture that depicts any kind of religious ritual or service. Because the theme of the frieze is unique we can not turn towards other relief sculpture to help us understand it.