Female Cyborgs, Gender Performance, and Utopian Gaze in Alex Garland’S Ex Machina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ex-Machina and the Feminine Body Through Human and Posthuman Dystopia

Elisabetta Di MINICO Ex-Machina and the Feminine Body through Human and Posthuman Dystopia Abstract: Ex-Machina is a 2015 sci-fi thriller, written and directed by Alex Garland, and starring Domhnall Gleeson, Oscar Isaac and Alicia Vikander. Critically acclaimed, the movie explores the relations between human and posthuman, as well as the relations between men and women. The article analyzes four main themes: the dystopian spaces of relations and conflicts between human and posthuman entities; the gender issues and the violent tendencies represented both in humans and in AIs; the construction and the representation of women’s bodies, roles, identities and images; the control and the manipulation perpetrated by “authoritarian” individuals on feminine bodies. The goal of my contribution is to show the reasons of the “double male fear of technology and of woman” (Huyssen 226), and I hope that my reflections could encourage a debate on posthumanism and on gendered power relations. Keywords: Human and Posthuman, Gender Issues, Dystopia. Ex-Machina is a 2015 sci-fi thriller, written and directed by Alex Garland, and starring Domhnall Gleeson, Oscar Isaac and Alicia Vikander. Acclaimed by critics, the movie ex- plores the relations between human and post- human, as well as the relations between men and women. With its lucid and tense writ- Elisabetta Di MINICO ing, Garland reflects on the possible dysto- University of Barcelona pian evolution of artificial intelligence, and Email: [email protected] he does that with no usual negative tenden- cy to create an evil sentient mechanism with- EKPHRASIS, 1/2017 out a cause. In the vision of Ex-Machina, both GHOSTS IN THE CINEMA MACHINE human and posthuman subjects contribute to pp. -

'Perry Mason' Lays Down the Law Anew On

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! June 19 - 25, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 E A D T Y E A W A H P Y F A Z Your Key I J P E C L K S N Z R A E T C 2 x 3" ad To Buying R E Q I P L Y U G R P O U E Y Matthew Rhys stars P F L U J R H A E L Y N P L R and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad F A R H O W E P L I T H G O W in “Perry Mason,” I F Y P N M A S E P Z X T J E premiering Sunday D E L L A Z R E S S E A M A G on HBO. Z P A R T R Y D L I G N S U S B F N Y H N E M H I O X L N N E R C H A L K D T J L N I A Y U R E L N X P S Y E Q G Y R F V T S R E D E M P T I O N H E E A Z P A V R J Z R W P E Y D M Y L U N L H Z O X A R Y S I A V E I F C I P W K R U V A H “Perry Mason” on HBO Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Perry (Mason) (Matthew) Rhys (Great) Depression Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Della (Street) (Juliet) Rylance (Los) Angeles ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Paul (Drake) (Chris) Chalk Origins Midlothian Mirror and Ellis (Sister) Alice (Tatiana) Maslany (Private) Investigator County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search (E.B.) Jonathan (John) Lithgow Redemption Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 ‘Perry Mason’ lays down for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Fleabag’ from London’S West End Expands Distribution in U.S

MEDIA ALERT – September 20, 2019 ‘Fleabag’ from London’s West End Expands Distribution in U.S. Cinemas Monday, November 18 for One Night See the critically acclaimed, award-winning one woman show that inspired the network series with BAFTA winner and Emmy nominee Phoebe Waller-Bridge • WHAT: Fathom Events, BY Experience and National Theatre Live release “Fleabag” in cinemas on Monday, November 18, 2019 at 7:00 p.m. local time, captured live from Wyndham’s Theatre London during its sell out West End run. • WHERE: Tickets for these events can be purchased online by visiting www.FathomEvents.com or at participating theater box offices. Fans throughout the U.S. will be able to enjoy the events in nearly 500 movie theaters through Fathom’s Digital Broadcast Network (DBN). For a complete list of theater locations visit the Fathom Events website (theaters and participants are subject to change). • WHO: Fathom Events, BY Experience and National Theatre Live “Filthy, funny, snarky and touching” Daily Telegraph “Witty, filthy and supreme” The Guardian “Gloriously Disruptive. Phoebe Waller-Bridge is a name to reckon with” The New York Times Fleabag Written by Phoebe Waller-Bridge and directed by Vicky Jones, Fleabag is a rip-roaring look at some sort of woman living her sort of life. Fleabag may appear emotionally unfiltered and oversexed, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. With family and friendships under strain and a guinea pig café struggling to keep afloat, Fleabag suddenly finds herself with nothing to lose. Fleabag was adapted into a BBC Three Television series in partnership with Amazon Prime Video in 2016 and earned Phoebe a BAFTA Award for Best Female Comedy Performance. -

Sci-Fi Sisters with Attitude Television September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE!

April 2021 Sky’s Intergalactic: Sci-fi sisters with attitude Television www.rts.org.uk September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE! R o y a l T e l e v i s i o n S o c i e t y b u r s a r i e s o f f e r f i n a n c i a l s u p p o r t a n d m e n t o r i n g t o p e o p l e s t u d y i n g : TTEELLEEVVIISSIIOONN PPRROODDUUCCTTIIOONN JJOOUURRNNAALLIISSMM EENNGGIINNEEEERRIINNGG CCOOMMPPUUTTEERR SSCCIIEENNCCEE PPHHYYSSIICCSS MMAATTHHSS F i r s t y e a r a n d s o o n - t o - b e s t u d e n t s s t u d y i n g r e l e v a n t u n d e r g r a d u a t e a n d H N D c o u r s e s a t L e v e l 5 o r 6 a r e e n c o u r a g e d t o a p p l y . F i n d o u t m o r e a t r t s . o r g . u k / b u r s a r i e s # R T S B u r s a r i e s Journal of The Royal Television Society April 2021 l Volume 58/4 From the CEO It’s been all systems winners were “an incredibly diverse” Finally, I am delighted to announce go this past month selection. -

Domhnall Gleeson, Thomas Haden Church, Christina Applegate Starring in Rom-Com ‘Crash Pad’ (EXCLUSIVE)

Editions: U.S SIGN IN Subscribe Today! FILM + TV + DIGITAL + CONTENDERS + VIDEO + DIRT + JOBS + MORE + HOME| FILM| NEWS Domhnall Gleeson, Thomas Haden Church, Christina Applegate Starring in Rom-Com ‘Crash Pad’ (EXCLUSIVE) EMAIL + 0 550 PRINT TALK Tweet OCTOBER 21, 2015 | 10:18AM PT REX SHUTTERSTOCK Dave McNary Film Reporter @Variety_DMcNary “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” star Domhnall Gleeson, Christina Applegate, Thomas Haden Church and Nina Dobrev are starring in the romantic comedy “Crash Pad,” which has started shooting in Vancouver, Variety has learned exclusively. Wonderful Films, Indomitable Entertainment, and Windowseat Entertainment are the production companies. Kevin Tent, the Oscar-nominated editor on Alexander Payne’s”The Descendants” and “Nebraska” is making his directorial debut with a Black List script by Jeremy Catalino. Gleeson stars as a hopeless romantic who thinks he’s found true love with an older woman, played by Applegate — only to learn that she’s married and that his fling is merely an instrument of revenge against her neglectful husband, played by Church. He threatens to blackmail her by telling her husband but his plan backfires when the husband decides the best way to get back at his wife is to move in with Gleeson’s character and adopt the slacker’s life of debauchery. Payne, who directed Haden Church in “Sideways,” is executive producing. Producers are William Horberg of Wonderful Films and Lauren Bratman. Besides Payne, the other exec producers are Dominic Ianno, Jon Ferro and Stuart Pollok of Indomitable Entertainment, Joseph McKelheer and Bill Kiely of Windowseat Entertainment, and Vicki Sotheran of Sodona Entertainment. -

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES BORD SCANNÁN NA Héireann / the IRISH FILM BOARD and BFI Present

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES BORD SCANNÁN NA hÉIREANN / THE IRISH FILM BOARD and BFI Present In Association with LIPSYNC PRODUCTIONS LLP A REPRISAL FILMS and OCTAGON FILMS Production BRENDAN GLEESON CHRIS O’DOWD KELLY REILLY AIDAN GILLEN DYLAN MORAN ISAACH DE BANKOLÉ M. EMMET WALSH MARIE-JOSÉE CROZE DOMHNALL GLEESON DAVID WILMOT PAT SHORTT GARY LYDON KILLIAN SCOTT ORLA O’ROURKE OWEN SHARPE DAVID McSAVAGE MÍCHEÁL ÓG LANE MARK O’HALLORAN DECLAN CONLON ANABEL SWEENEY WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY.................................. JOHN MICHAEL McDONAGH PRODUCED BY ............................................................ CHRIS CLARK ........................................................................................ FLORA FERNANDEZ MARENGO ........................................................................................ JAMES FLYNN EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS ......................................... ROBERT WALAK ........................................................................................ RONAN FLYNN CO-PRODUCERS .......................................................... ELIZABETH EVES ........................................................................................ AARON FARRELL DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY ................................ LARRY SMITH BSC CASTING ....................................................................... JINA JAY PRODUCTION DESIGNER .......................................... MARK GERAGHTY EDITOR.......................................................................... CHRIS GILL COSTUME DESIGNER................................................ -

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES Presents a DJ FILMS / GASWORKS

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES Presents A DJ FILMS / GASWORKS MEDIA Production DOMHNALL GLEESON MARGOT ROBBIE KELLY MACDONALD ALEX LAWTHER STEPHEN CAMPBELL MOORE VICKI PEPPERDINE RICHARD McCABE GERALDINE SOMERVILLE PHOEBE WALLER-BRIDGE Introducing WILL TILSTON DIRECTED BY .......................................................... SIMON CURTIS WRITTEN BY ........................................................... FRANK COTTRELL-BOYCE .................................................................................... SIMON VAUGHAN PRODUCED BY ........................................................ DAMIAN JONES p.g.a. .................................................................................... STEVE CHRISTIAN p.g.a. DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY ........................... BEN SMITHARD BSC PRODUCTION DESIGNER ..................................... DAVID ROGER FILM EDITOR ........................................................... VICTORIA BOYDELL EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS ..................................... SIMON CURTIS .................................................................................... SIMON VAUGHAN CO-PRODUCER ........................................................ MARK HUBBARD COSTUME DESIGNER ............................................ ODILE DICKS-MIREAUX HAIR, MAKE-UP & PROSTHETICS DESIGNER .. SIAN GRIGG MUSIC BY ................................................................. CARTER BURWELL MUSIC SUPERVISOR .............................................. SARAH BRIDGE CASTING BY .......................................................... -

Analyzing Cultural Representations of State Control in Black Mirror Carl Russell Huber Eastern Kentucky University

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship January 2017 A Dark Reflection of Society: Analyzing Cultural Representations of State Control in Black Mirror Carl Russell Huber Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Criminology Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Huber, Carl Russell, "A Dark Reflection of Society: Analyzing Cultural Representations of State Control in Black Mirror" (2017). Online Theses and Dissertations. 454. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/454 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Dark Reflection of Society: Analyzing Cultural Representations of State Control in Black Mirror By CARL R. HUBER Bachelor of Science Central Michigan University Mount Pleasant, MI 2015 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 2017 Copyright © Carl Russell Huber, 2017 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Judah Schept for his knowledge, guid- ance, and insight. I would also like to thank the other committee members, Dr. Victoria Collins and Dr. Travis Linnemann for their comments and assistance. I would also like to express my thanks to Dr. Justin Smith, who has mentored me throughout my academic career and has help shape my research. -

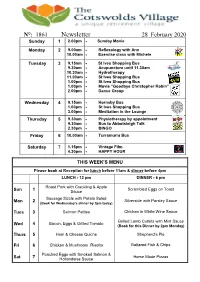

Newsletter 28Th Feb.Pub

N°: 1861 Newsletter 28 February 2020 Sunday 1 2.00pm • Sunday Movie Monday 2 9.00am • Reflexology with Ann 10.00am • Exercise class with Michele Tuesday 3 9.15am • St Ives Shopping Bus 9.30am • Acupuncture until 11.30am 10.30am • Hydrotherapy 11.00am • St Ives Shopping Bus 1.00pm • St Ives Shopping Bus 1.00pm • Movie “Goodbye Christopher Robin” 2.00pm • Dance Group Wednesday 4 9.15am • Hornsby Bus 1.00pm • St Ives Shopping Bus 3.00pm • Meditation in the Lounge Thursday 5 9.30am • Physiotherapy by appointment 9.30am • Bus to Abbotsleigh Talk 2.30pm • BINGO Friday 6 10.00am • Turramurra Bus Saturday 7 1.15pm • Vintage Film 4.30pm • HAPPY HOUR THIS WEEK’S MENU Please book at Reception for lunch before 11am & dinner before 4pm LUNCH - 12 pm DINNER - 6 pm Roast Pork with Crackling & Apple Sun 1 Scrambled Eggs on Toast Sauce Sausage Sizzle with Potato Salad Mon 2 Silverside with Parsley Sauce (Book for Wednesday’s dinner by 2pm today) Tues 3 Salmon Patties Chicken in White Wine Sauce Grilled Lamb Cutlets with Mint Sauce Wed 4 Bacon, Eggs & Grilled Tomato (Book for this Dinner by 2pm Monday) Thurs 5 Ham & Cheese Quiche Shepherd’s Pie Fri 6 Chicken & Mushroom Risotto Battered Fish & Chips Poached Eggs with Smoked Salmon & 7 Home Made Pizzas Sat Hollandaise Sauce ENTERTAINMENT PETER'S VINTAGE FILMS Come and enjoy an afternoon of nostalgia. Re-visit your favourite stars from the 1930s to the '80s as Judith presents the best from that golden age of film-making. SATURDAY 29th February at 1:15 pm The film of Bizet's opera "CARMEN" Filmed on location in Spain in 1984, this colourful French production stars Julia Migenes-Johnson as a feisty and sensuous Carmen with Placido Domingo as Don José, and Ruggero Raimondi as Escamillo. -

The Top 10 Television Series of 2020, a Year When TV Was a Sanctuary and Escape

TELEVISION CANADA WORLD BUSINESS INVESTING OPINION POLITICS SPORTS LIFE ARTS DRIVE OPINION The top 10 television series of 2020, a year when TV was a sanctuary and escape JOHN DOYLE TELEVISION CRITIC PUBLISHED 1 DAY AGO FOR SUBSCRIBERS 63 COMMENTS SHARE TEXT SIZE BOOKMARK Plan your screen time with the weekly What to Watch newsletter, with film, TV and streaming reviews and more. Sign up today. In this, the weirdest year we have lived through, television saved us. A sanctuary of escapism, it was also the lifeboat, the saviour of sanity and a reminder that there’s normal life, filled with joy, companionship, touching, talking unmasked, travelling to places and feeling safe. Where people went with their TV viewing makes a top-10 list slightly dubious. One person’s safe escape was another person’s masterpiece. People watched more TV than ever as the pandemic shut down everything. What they found, often, was storytelling of the highest calibre. And art – this was also a year of confident experimentation. Binge-watching guide: The recent shows you need to catch up on, all available to stream Two HBO shows dabbled in unreliable narration, in I May Destroy You, with its jangled, nerve-wracking reconstruction of a sexual assault, and The Third Day, with its unique structure, featuring separate characters experiencing the same mental dislocation, and a live, one-off episode. These were praiseworthy and unsettling, but some of the year’s finest content was comforting, even as it challenged. Such was the second season of Ricky Gervais’s beautifully modulated After Life on Netflix. -

Deirdre Kinahan Louise Lowe Marie Mullen Brian Gleeson

LANDMARK PRODUCTIONS BY DEIRDRE KINAHAN DIRECTED BY LOUISE LOWE STARRING MARIE MULLEN AND BRIAN GLEESON WORLD PREMIERE BY DEIRDRE KINAHAN DIRECTOR LOUISE LOWE COMPOSER CONOR MITCHELL COSTUME DESIGNER JOAN O’CLERY LIGHTING DESIGNER MARY TUMELTY SOUND DESIGNER CAMERON MACAULAY BROADCAST LIVE FROM THE EVERYMAN THEATRE AS PART OF CORK MIDSUMMER FESTIVAL SATURDAY 19 JUNE 2021, 3PM AND 8PM SUNDAY 20 JUNE 2021, 8PM ON DEMAND 21–27 JUNE Marie Mullen in rehearsal. Photo: Barry Cronin 2 3 CONTENTS LANDMARK PRODUCTIONS Landmark Productions is one of work – plays, operas and musicals Ireland’s leading theatre producers. – in theatres ranging from the 66- It produces wide-ranging work in seat New Theatre to the 1,254- PAGE 5 LANDMARK PRODUCTIONS Ireland, and shares that work with seat Olympia. It co-produces international audiences. regularly with a number of partners, including, most significantly, Galway PAGE 6 THE SACRED TRUTH In January 2021 it launched Landmark International Arts Festival and Live, a new online streaming platform Irish National Opera. Its 21 world OF MÁIRE SULLIVAN to enable the company to bring the premieres include new plays by major thrill of live theatre to audiences Irish writers such as Enda Walsh and around the world. Mark O’Rowe, featuring a roll-call of PAGE 9 CAST / CREATIVES Ireland’s finest actors, directors and Deirdre Kinahan’s The Saviour is the designers. fourth production to be streamed to PAGE 26 LANDMARK LIVE date. In August, Landmark, in a co- Numerous awards include the production with Galway International Judges’ Special Award at The Irish Arts Festival, will present the world Times Irish Theatre Awards, in premiere of a new play by Enda Walsh, recognition of ‘sustained excellence PAGE 28 THANK YOUS / FUNDING Medicine, as part of the Edinburgh in programming and for developing International Festival. -

Richard Curtis Writer/Director

Richard Curtis Writer/Director Agents Anthony Jones Associate Agent Danielle Walker [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0858 Credits In Development Production Company Notes THAT CHRISTMAS Locksmith Animation/Netflix Animated film written with Peter Souter, based on his children's novel Illustrator: Rebecca Cobb Executive Producer: Colin Hopkins LOST FOR WORDS Working Title Films With Jamie Curtis BERNARD AND THE GENIE Film Production Company Notes YESTERDAY Working Title Original screenplay 2019 Films/Universal Directed by Danny Boyle with Himesh Patel & Lily James TRASH Working Title Films Adapted from the novel by Andy Mulligan 2014 Directed by Stephen Daldry with Martin Sheen, Rooney Mara ESIO TROT BBC TV Film 2014 Based on the novel by Roald Dahl Co-written with Paul Mayhew-Archer Produced by Hilary Bevan Jones Directed by Dearbhla Walsh With Judi Dench & Dustin Hoffman United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes ABOUT TIME Working Original Screenplay 2013 Title/Universal Pictures Writer and Director Produced by Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Nicky Kentish Barnes with Domhnall Gleeson, Rachel McAdams, Bill Nighy *Won Best European Film San Sebastian International Film Festival 2013 *Nominated Best Film New York Film Festival 2013 MARY AND MARTHA Working Title TV Film 2013 Television/HBO Original Screenplay Directed by Phillip Noyce Produced by Hilary Bevan Jones, Lisa Bruce, Genevieve Hofmeyr with Hilary Swank, Brenda