The Popular Culture Studies Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Superman Ebook, Epub

SUPERMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jerry Siegel | 144 pages | 30 Jun 2009 | DC Comics | 9781401222581 | English | New York, NY, United States Superman PDF Book The next event occurs when Superman travels to Mars to help a group of astronauts battle Metalek, an alien machine bent on recreating its home world. He was voiced in all the incarnations of the Super Friends by Danny Dark. He is happily married with kids and good relations with everyone but his father, Jor-EL. American photographer Richard Avedon was best known for his work in the fashion world and for his minimalist, large-scale character-revealing portraits. As an adult, he moves to the bustling City of Tomorrow, Metropolis, becoming a field reporter for the Daily Planet newspaper, and donning the identity of Superman. Superwoman Earth 11 Justice Guild. James Denton All-Star Superman Superman then became accepted as a hero in both Metropolis and the world over. Raised by kindly farmers Jonathan and Martha Kent, young Clark discovers the source of his superhuman powers and moves to Metropolis to fight evil. Superman Earth -1 The Devastator. The next few days are not easy for Clark, as he is fired from the Daily Planet by an angry Perry, who felt betrayed that Clark kept such an important secret from him. Golden Age Superman is designated as an Earth-2 inhabitant. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Filming on the series began in the fall. He tells Atom he is welcome to stay while Atom searches for the people he loves. -

Comparative Literature

ProgramComparative in Literature The university of texas at austin Letter from the Director Comparative Literature News Dear Colleagues, Spring 2007 This year brought with it a combination of collegial conversations amongst ourselves and exceptional Letter from the Director 1 successes and visibility both across the campus and beyond. The Third Annual Graduate Comparative Program News Literature Conference “High Concept: Comparative Studies Out in the World” in October 2006, with its Incoming Graduate Students 2 energetic and provocative plenary address by Dr. Note from GRACLS 2 David Damrosch of Columbia University, invited Fall 2007 Courses 3 us to engage each other’s work and consider its place in the world we inhabit. Student News and Profiles Indeed the achievements of our colleagues and students, which you will read about in these Degree Recipients 4 pages, whether in the context of scholarships and Elizabeth Fernea Fellowship 4 awards, publications and presentations, whether Prizes and Fellowships 5 local, national or international, remain varied, New Student Profiles 6 admired and vital. With faculty on their way to 2006 GRACLS Conference 7 Rome and Cairo, and students regularly winning Student Profiles the most competitive of awards and prizes, we Marina Alexandrova 8 have flourished this year thanks to the generosity of our dean and the wise guidance of our graduate Heather Latiolais 8 adviser, Dolora Chapelle Wojciehowski. Christopher Micklethwait 9 Aména Moïnfar 9 The program continues to serve as the home of Anna Katsnelson 10 the American Comparative Literature Association, Hyunjung Lee 10 whose membership has tripled to 1,400 in the Vessela Valiavitcharska 11 past four years, and as the major resource in the discipline in North America and beyond, defining Faculty News and Profiles 12 and developing the field in transnational and interdisciplinary ways so as fully to reflect and enable the growth of our field in our complex and Alumni News and Profiles 13 varied world. -

2019 Connections Fall

Strebe becomes an Ultraman Fall 2019 Alumni Association and Development Foundation CONGRATULATIONS to four outstanding alumni SARA (BIRKELAND) MEDALEN ’90/’09, a reading and math interventionist at Minot’s Sunnyside Elementary School, is the North Dakota Teacher of the Year for 2020. Medalen assists students in grades K – 5 who are struggling with reading or math. She has also started programs to encourage reading, leadership development, and physical fitness. Medalen oversees STEAM Saturdays (Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts, Mathematics), which encourages students to collaborate, use critical thinking and problem-solving skills, take risks, and learn from andfailure. help Medalen students also learn founded about healthyStrides habits.for Sunnyside, a running group for students, to promote physical activity TANYA (POTTER) BURKE ’99, a radiation therapist with Trinity Health’s CancerCare Center, received the Award. The award was established as a national initia- tivefirst toBeekley recognize Medical professionals Radiation in Therapy various Empower cancer care disciplines across the U.S. for efforts to improve care for patients and their families. KRISTI (PATTERSON) REINKE ’01/’04/’08, thea history Year. teacher at Jim Hill Middle School, was named Minot Education Association Teacher of SARA (CARLSON) DEUTSCH ’02 teaches physical education at Jim Hill Middle School. She was honored with the NDSHAPE Middle School Teacher of the Year award. 2 CONNECTIONS Fall ’19 President’s message CONNECTIONS STAFF s I write this column, it is mid-October and I am Vice President for Advancement out of state missing an early-season winter storm Rick Hedberg ’89 back home in Minot. We can expect snow and Managing Editor Michael Linnell wind virtually any time of the year, but even unusual. -

Forever Evil: Rogues Rebellion Free

FREE FOREVER EVIL: ROGUES REBELLION PDF Scott Hepburn,Patrick Zircher,Brian Buccellato | 192 pages | 07 Oct 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401249410 | English | United States Forever Evil: Rogues Rebellion by Brian Buccellato Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Forever Evil: Rogues Rebellion and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Forever Evil by Brian Buccellato. Scott Hepburn Illustrator. Patrick Zircher Illustrator. The Rogues — the Flash's gallery of villains — call no man boss, but a new evil threat might not leave them much choice! Will they fall in line, or refuse and risk certain death? Will the Rogues be able to take on the Crime Syndicate together? Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. The Flash 4. Other Editions 2. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, Forever Evil: Rogues Rebellion sign up. To ask other readers questions about Forever Evilplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of Forever Evil: Rogues Rebellion. Aug 19, Jayson rated it liked it Forever Evil: Rogues Rebellion comic-book-limited-seriesformat-comic-booksubject-parallel-universeauthor- americangenre-companiongenre-superheroppcomics-dc-newread-ingenre-antihero. View all 8 comments. Aug 14, Jeff rated it liked it Shelves: comix. The catch: They have to destroy Central City. Out with the old in with the new! Do it! Get it done! Oh wait! The party has started without them. -

Chapter Iii Analysis

A l i y a h | 21 CHAPTER III ANALYSIS In this chapter, the writer intends to analyze about Oscar’s life in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao through the formal elements of the novel, especially character, tragedy and tragic hero. The first step of the analysis describes Oscar’s tragedy presented in the novel. The second step of the analysis is explaining the process of the way the tragedy leads Oscar to be tragic hero. In this process of the analysis, the writer takes a look at the formal elements of tragedy and tragic hero which describe from the beginning how the character is created until it changes in the end of the story. 3.1 Tragedy in Oscar Life This part aims to depict the tragedy in The Brief wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. The tragedy in this novel was depicted from the story’s plot. As stated in the background of study, The Brief wondrous Life of Oscar Wao was written by Dominican author Junot Diaz. The story is set in the United States and in the Dominican Republic. The story relates the character experience of being Dominican in both places. The Brief wondrous Life of Oscar Wao won pulitzer price for fiction in 2008. To support the analysis in this chapter, the theory from Aristotle, The Mythos of Autumn: Tragedy will be used as the primary concept. As stated before, the story digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id A l i y a h | 22 can be called as tragedy if the story comply the pattern of tragedy itself. -

Existentialism of DC Comics' Superman

Word and Text Vol. VII 151 – 167 A Journal of Literary Studies and Linguistics 2017 Re-theorizing the Problem of Identity and the Onto- Existentialism of DC Comics’ Superman Kwasu David Tembo University of Edinburgh E-mail: [email protected] Abstract One of the central onto-existential tensions at play within the contemporary comic book superhero is the tension between identity and disguise. Contemporary comic book scholarship typically posits this phenomenon as being primarily a problem of dual identity. Like most comic book superheroes, superbeings, and costumed crime fighters who avail themselves of multiple identities as an essential part of their aesthetic and narratological repertoire, DC Comics character Superman is also conventionally aggregated in this analytical framework. While much scholarly attention has been directed toward the thematic and cultural tensions between two of the character’s best-known and most recognizable identities, namely ‘Clark Kent of Kansas’ and ‘Superman of Earth’, the character in question is in fact an identarian multiplicity consisting of three ‘identity-machines’: ‘Clark’, ‘Superman’, and ‘Kal-El of Krypton’. Referring to the schizoanalysis developed by the French theorists Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in Anti- Oedipus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia (orig. 1972), as well as relying on the kind of narratological approach developed in the 1960s, this paper seeks to re-theorize the onto- existential tension between the character’s triplicate identities which the current scholarly interpretation of the character’s relationship with various concepts of identity overlooks. Keywords: Superman, identity, comic books, Deleuze and Guattari, schizoanalysis The Problem of Identity: Fingeroth and Dual Identities Evidenced by the work of contemporary comic book scholars, creators, and commentators, there is a tradition of analysis that typically understands the problem of identity at play in Superman, and most comic book superheroes by extension, as primarily a problem of duality. -

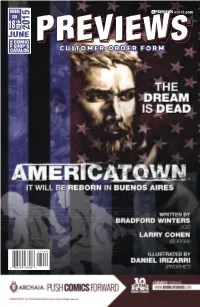

Customer Order Form June

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 JUNE 2015 JUNE COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jun15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/7/2015 3:00:50 PM June15 C2 Future Dude.indd 1 5/6/2015 11:24:23 AM KING TIGER #1 HE-MAN AND THE DARK HORSE COMICS MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE MINI-COMIC COLLECTION HC DARK HORSE COMICS JUSTICE LEAGUE: GODS AND MONSTERS #1 DC COMICS GET JIRO: BLOOD AND SUSHI THE X-FILES: DC COMICS/VERTIGO SEASON 11 #1 IDW PUBLISHING DARK CORRIDOR #1 IMAGE COMICS PHONOGRAM: THE IMMATERIAL ANT-MAN: GIRL #1 LAST DAYS #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS Jun15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/6/2015 4:38:32 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Girl Genius: The Second Journey Volume 1 TP/HC l AIRSHIP ENTERTAINMENT War Stories Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC War Stories Volume 2 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Over The Garden Wall #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS The Shadow #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Red Sonja/Conan #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Space Dumplins GN/HC l GRAPHIX Stringers #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Little Nemo: Big New Dreams HC l TOON GRAPHICS Kill La Kill Volume 1 GN l UDON ENTERTAINMENT CORP Book of Death: Fall of Ninjak #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Ultraman Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS The Doctors Are In: The Essential and Unofficial Guide to Doctor Who l DOCTOR WHO Star Wars: The Original Topps Trading Card Series Volume 1 HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES The Walking Dead Figurine Magazine l EAGLEMOSS DC Masterpiece Figurine Collection #2: Femme Fatales Set l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #6 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man -

Spider-Woman

DC MARVEL IMAGE ! ACTION ! ALIEN ! ASCENDER ! AMERICAN VAMPIRE 1976 ! AMAZING SPIDER-MAN ! BIRTHRIGHT ! AQUAMAN ! AVENGERS ! BITTER ROOT ! BATGIRL ! AVENGERS: MECH STRIKE 1-5 ! BLISS 1-8 ! BATMAN ! BETA RAY BILL 1-5 ! COMMANDERS IN CRISIS 1-12 ! BATMAN ADVENTURES CONTINUE ! BLACK CAT ! CROSSOVER ! BATMAN BLACK & WHITE 1-6 ! BLACK KNIGHT CURSE EBONY BLADE ! DEADLY CLASS ! BATMAN: URBAN LEGENDS ! BLACK WIDOW ! DECORUM ! BATMAN/CATWOMAN 1-12 ! CABLE ! DEEP BEYOND ! BATMAN/SUPERMAN ! CAPTAIN AMERICA ! DEPARTMENT OF TRUTH ! CATWOMAN ! CAPTAIN MARVEL ! EXCELLENCE ! CRIME SYNDICATE ! CARNAGE BW & BLOOD 1-4 ! FAMILY TREE ! DETECTIVE COMICS ! CHAMPIONS ! FIRE POWER ! DREAMING : WAKING HOURS ! CHILDREN OF THE ATOM ! GEIGER ! FAR SECTOR ! CONAN THE BARBARIAN ! ICE CREAM MAN ! FLASH ! DAREDEVIL ! JUPITERS LEGACY 1-5 ! GREEN ARROW ! DEADPOOL ! KARMEN 1-5 ! GREEN LANTERN ! DEMON DAYS X-MEN 1-5 ! KILLADELPHIA ! HARLEY QUINN ! ETERNALS ! LOW ! INFINITE FRONTIER ! EXCALIBUR ! MONSTRESS ! JOKER ! FANTASTIC 4 ! MOONSHINE ! JUSTICE LEAGUE ! FANTASTIC 4 LIFE STORY 1-6 ! NOCTERRA ! LAST GOD ! GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY ! OBLIVION SONG ! LEGENDS OF DARK KNIGHT ! HELLIONS ! OLD GUARD 1-6 ! LEGION of SUPER-HEROES ! HEROES REBORN 1-7 ! POST AMERICANA 1-6 ! MAN-BAT ! IMMORTAL HULK ! RADIANT BLACK ! NEXT BATMAN: SECOND SON ! IRON FIST Heart of Dragon 1-6 ! RAT QUEENS ! NIGHTWING ! IRON MAN ! REDNECK ! OTHER HISTORY DC UNIVERSE ! MAESTRO WAR & PAX 1-5 ! SAVAGE DRAGON ! RED HOOD ! MAGNIFICENT MS MARVEL ! SEA OF STARS ! RORSCHACH ! MARAUDERS ! SILVER COIN 1-5 ! SENSATIONAL -

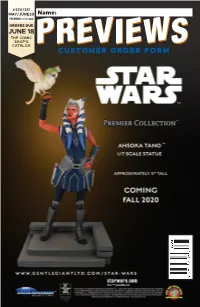

Customer Order Form

#380/381 MAY/JUNE20 Name: PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE JUNE 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Cover COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 1:41:01 PM FirstSecondAd.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:49:06 PM PREMIER COMICS BIG GIRLS #1 IMAGE COMICS LOST SOLDIERS #1 IMAGE COMICS RICK AND MORTY CHARACTER GUIDE HC DARK HORSE COMICS DADDY DAUGHTER DAY HC DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: THREE JOKERS #1 DC COMICS SWAMP THING: TWIN BRANCHES TP DC COMICS TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: THE LAST RONIN #1 IDW PUBLISHING LOCKE & KEY: …IN PALE BATTALIONS GO… #1 IDW PUBLISHING FANTASTIC FOUR: ANTITHESIS #1 MARVEL COMICS MARS ATTACKS RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SEVEN SECRETS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS MayJune20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:41:00 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Cimmerian: The People of the Black Circle #1 l ABLAZE 1 Sunlight GN l CLOVER PRESS, LLC The Cloven Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS The Big Tease: The Art of Bruce Timm SC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Totally Turtles Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS 1 Heavy Metal #300 l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist l HERMES PRESS Titan SC l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: Mistress of Chaos TP l PANINI UK LTD Kerry and the Knight of the Forest GN/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC Masterpieces of Fantasy Art HC l TASCHEN AMERICA Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics Hc Gn l TEN SPEED PRESS Horizon: Zero Dawn #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2019 #9 l TITAN COMICS Negalyod: The God Network HC l TITAN COMICS Star Wars: The Mandalorian: -

Justice League Crisis on Two Earths Download Mp4 Justice League: Crisis on Two Earths Blu-Ray Review

justice league crisis on two earths download mp4 Justice League: Crisis on Two Earths Blu-ray Review. The Justice League meets their evil counterparts. You can guess what happens next. Those who want to see the seeds of that connection between Crisis and the television incarnations of the Justice League won't have to look very hard. The character designs are similar, and although the lineup of heroes is slightly different, it begins with a small, core team working on the satellite that will eventually become the base of operations for a larger cast of characters. The main cast includes Superman, Wonder Woman, Batman, Flash, Martian Manhunter and Green Lantern (Hal Jordon, not John Stewart, as in the TV series). There are also cameos galore, including some characters we already know and their evil alter egos from a parallel world (who are fun to figure out if you know anything about the DC Universe). To further distance this story from the others that have come before, there have been some voice cast changes as well. The new voices take some getting used to, and in some cases it's tough to get over the image that goes along with the voice. But once the well-animated action kicks in, you'll start to see Batman instead of William ("Billy") Baldwin, Superman instead of Mark Harmon and Lex Luthor instead of Chris Noth. Not to be outdone, the villains also have some marquee names to their credits, with none other than James Woods providing the subtly sinister voice of alt- universe Batman, known in his world as Owl Man, and Gina Torres sounding at once seductive and strong as Super Woman, an evil counterpart to Wonder Woman. -

Ultraman: 3 Free

FREE ULTRAMAN: 3 PDF Tomohiro Shimoguchi,Eiichi Shimizu | 188 pages | 24 Mar 2016 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421581842 | English | San Francisco, United States Ultraman (Earth-3) | DC Database | Fandom It is the 32nd entry to the Ultra Series and the first entry to the post-New Generation Hero lineup, meant to celebrate the 10th anniversary of Ultraman Zero. Following the destruction of Ultraman Belial in Ultraman Geedthe Devil Splinters were scattered and turn monsters into berserker, causing chaos throughout the universes. At the end of a Ultraman: 3 battle, Z chases Genegarg alone, making his way towards Earth. When a monster from space invades Earth, Z and Haruki have their fateful encounter [4] [5] [6] [7] while Celebro started to plan his schemes. Ultraman Z was immediately announced by official website of Tsuburaya Productions on March Ultraman: 3, This happened at some point before the series premiere on June In addition to being a prequel series, the title character of Ultraman Z made his appearance as one of the characters involved. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Television series. Main article: List of Ultraman Z characters. Ultraman: 3 article: Ultraman: 3 of Ultraman Z episodes. Retrieved 2 Ultraman: 3 Reruns will be available for anyone who misses the show! Tsuburaya Productions. Retrieved 14 September Retrieved 26 March Cinema Today. Game Watch. Retrieved Retrieved 8 June Ultraman: 3 16 April Car Watch. Retrieved 20 June Ultraman: 3 Nikkan Sports. Ultraman: 3 Annex. Retrieved 15 August Retrieved 19 June Ultraman Galaxy. Retrieved 5 May Retrieved 19 May Retrieved 19 September Retrieved 4 September Ultra Series.