Sticky Whiteleaf Manzanita Plant Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

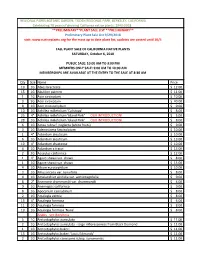

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Arctostaphylos Hispidula, Gasquet Manzanita

Conservation Assessment for Gasquet Manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) Within the State of Oregon Photo by Clint Emerson March 2010 U.S.D.A. Forest Service Region 6 and U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Author CLINT EMERSON is a botanist, USDA Forest Service, Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, Gold Beach and Powers Ranger District, Gold Beach, OR 97465 TABLE OF CONTENTS Disclaimer 3 Executive Summary 3 List of Tables and Figures 5 I. Introduction 6 A. Goal 6 B. Scope 6 C. Management Status 7 II. Classification and Description 8 A. Nomenclature and Taxonomy 8 B. Species Description 9 C. Regional Differences 9 D. Similar Species 10 III. Biology and Ecology 14 A. Life History and Reproductive Biology 14 B. Range, Distribution, and Abundance 16 C. Population Trends and Demography 19 D. Habitat 21 E. Ecological Considerations 25 IV. Conservation 26 A. Conservation Threats 26 B. Conservation Status 28 C. Known Management Approaches 32 D. Management Considerations 33 V. Research, Inventory, and Monitoring Opportunities 35 Definitions of Terms Used (Glossary) 39 Acknowledgements 41 References 42 Appendix A. Table of Known Sites in Oregon 45 2 Disclaimer This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile existing published and unpublished information for the rare vascular plant Gasquet manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) as well as include observational field data gathered during the 2008 field season. This Assessment does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service (Region 6) or Oregon/Washington BLM. Although the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. -

Adenostoma Fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos Canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos Virgata (Marin Manzanita) Alison S

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 5-20-2016 Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species--Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita) Alison S. Pollack University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Pollack, Alison S., "Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species-- Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita)" (2016). Master's Projects and Capstones. 352. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/352 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 This Master's Project Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species--Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita) by Alison S. Pollack is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Science in Environmental Management at the University of San Francisco Submitted: Received: ................................…………. -

Historical Vegetation of Central Southwest Oregon, Based on GLO

HISTORICAL VEGETATION OF CENTRAL SOUTHWEST OREGON, BASED ON GLO SURVEY NOTES Final Report to USDI BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Medford District October 31, 2011 By O. Eugene Hickman and John A. Christy Consulting Rangeland Ecologist Oregon Biodiversity Information Center Retired, USDA - NRCS Portland State University 61851 Dobbin Road PSU – INR, P.O. Box 751 Bend, Oregon 97702 Portland, Oregon 97207-0751 (541, 312-2512) (503, 725-9953) [email protected] [email protected] Suggested citation: Hickman, O. Eugene and John A. Christy. 2011. Historical Vegetation of Central Southwest Oregon Based on GLO Survey Notes. Final Report to USDI Bureau of Land Management. Medford District, Oregon. 124 pp. ______________________________________________________________________________ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 7 SW OREGON PRE-GLO SURVEY HISTORY ....................................................................................................................... 7 THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE, ITS FUNCTION AND HISTORY........................................................................................... -

Arctostaphylos Photos Susan Mcdougall Arctostaphylos Andersonii

Arctostaphylos photos Susan McDougall Arctostaphylos andersonii Santa Cruz Manzanita Arctostaphylos auriculata Mount Diablo Manzanita Arctostaphylos bakeri ssp. bakeri Baker's Manzanita Arctostaphylos bakeri ssp. sublaevis The Cedars Manzanita Arctostaphylos canescens ssp. canescens Hoary Manzanita Arctostaphylos canescens ssp. sonomensis Sonoma Canescent Manzanita Arctostaphylos catalinae Catalina Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos columbiana Columbia Manzanita Arctostaphylos confertiflora Santa Rosa Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. crinita Crinite Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. crustacea Brittleleaf Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. rosei Rose's Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. subcordata Santa Cruz Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos cruzensis Arroyo De La Cruz Manzanita Arctostaphylos densiflora Vine Hill Manzanita Arctostaphylos edmundsii Little Sur Manzanita Arctostaphylos franciscana Franciscan Manzanita Arctostaphylos gabilanensis Gabilan Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. adamsii Adam's Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. crassifolia Del Mar Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. cushingiana Cushing's Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. glandulosa Eastwood Manzanita Arctostaphylos glauca Big berry Manzanita Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. hearstiorum Hearst's Manzanita Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. hookeri Hooker's Manzanita Arctostaphylos hooveri Hoover’s Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. howellii Howell's Manzanita Arctostaphylos insularis Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos luciana -

Ione Buckwheat), and Discussion of the Two Species Proposed RIN 1018±AE25 Eriogonum Apricum Var

34190 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 122 / Wednesday, June 25, 1997 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: nutrient-poor conditions of the soil Background which exclude other plant species; the Fish and Wildlife Service climate of the area may be moderated by Arctostaphylos myrtifolia (Ione its position due east of the Golden Gate 50 CFR Part 17 manzanita), Eriogonum apricum var. (Gankin and Major 1964, Roof 1982). apricum (Ione buckwheat), and Discussion of the Two Species Proposed RIN 1018±AE25 Eriogonum apricum var. prostratum (Irish Hill buckwheat) are found for Listing Endangered and Threatened Wildlife primarily in western Amador County, Parry (1887) described Arctostaphylos and Plants; Proposed Endangered about 70 kilometers (km) (40 miles (mi)) myrtifolia based upon material collected Status for the Plant Eriogonum southeast of Sacramento in the central near Ione, California. Subsequent Apricum (Ione Buckwheat) and Sierra Nevada foothills of California. authors variously treated this taxon as Proposed Threatened Status for the Most populations occur at elevations Uva-ursi myrtifolia (Abrams 1914), A. Plant Arctostaphylos Myrtifolia (Ione between 90 and 280 meters (m) (280 to nummularia var. myrtifolia (Jepson Manzanita) 900 feet (ft)). A few isolated occurrences 1922), Schizococcus myrtifolius of A. myrtifolia occur in adjacent (Eastwood 1934), and Arctostaphylos AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, northern Calaveras County. uva-ursi ssp. myrtifolia (Roof 1982). Interior. Both species included in -

44 Old-Growth Chaparral 12/20

THE CHAPARRALIAN December 25, 2020 #44 Volume 10, Issue 1 2 The Chaparralian #44 Contents 3 The Legacy of Old-Growth Chaparral 4 The Photography of Chaparralian Alexander S. Kunz 8 A New Vision for Chaparral 11 The Dance Between Arctostaphylos and Ceanothus 14 Unfoldings Cover photograph: A magnificent old-growth red shanks or ribbonwood (Adenostoma sparsifolium) with a chaparral elf exploring its The Chaparralian is the periodic journal of the California Chaparral branches. Photo taken in the Descanso Ranger Institute, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to the District, Cleveland National Forest, by Richard preservation of native shrubland ecosystems and supporting the W. Halsey. creative spirit as inspired by Nature. To join the Institute and receive The Chaparralian, please visit our website or fill out and Photo upper left: Old-growth manzanita in The mail in the slip below. We welcome unsolicited submissions to the fabulous Burton Mesa Ecological Preserve, Chaparralian. Please send to: [email protected] or via near Lompoc, CA. The reserve is a 5,368-acre post to the address below. protected area, managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. In this photo, You can find us on the web at: https://californiachaparral.org/ an ephemeral Chaparrailan enjoys the ancient, twisting branches of the rare, endemic Purisima Publisher................................... Richard W. Halsey manzanita (Arctostaphylos purissima). Photo by Editor....................................... Dylan Tweed Richard W. Halsey. Please Join the California Chaparral Institute and support our research and educational efforts to help promote a better understanding of and appreciation for the remarkable biodiversity found in shrubland ecosystems and to encourage the creative spirit as inspired by Nature. -

Definition of Maritime Chaparral in the Manual of California Vegetation

Definition of Maritime Chaparral What is Maritime Chaparral? (Focus: Northern and Central Maritime Chaparral) in the Manual of California Vegetation John O. Sawyer, Humboldt State University Professor Emeritus Julie M. Evens, California Native Plant Society Vegetation Ecologist Shrublands whose plants have sclerophyllous leaves and grow in Many habitats contain distinctive nutrient-poor soils on windward uplands plant species and characteristic and coastal lowlands of northern and vegetation types that make habitats central California (from Mendocino to easy to distinguish from Santa Barbara Cos.). other habitats. “The kind of site or region with Northern/Central Maritime Chaparral respect to physical features (as soil, weather, elevation) naturally or exists on California’s coast normally preferred by a biological between southern Mendocino and species” – Merriam-Webster Dictionary Santa Barbara Cos. Alkali sinks, fens, freshwater marshes, salt marshes, vernal pools 1 Maritime chaparral Maritime chaparral contains plants adapted to areas has nutrient-poor soils and occurs with cool, foggy summers, unlike on windward uplands and coastal interior chaparral types (where lowlands summers are not moderated by fog) In maritime chaparral – Maritime chaparral Periodic burning is necessary for includes Arctostaphylos or renewal of plant populations that Ceanothus species, including any characterize the habitat. narrow endemics considered rare and endangered. Recent fire suppression practices have reduced the size and They characterize the habitat. frequency of wildfires in the habitat. In maritime chaparral – In maritime chaparral – Recent conditions favor longer- lived Agricultural conversion, residential shrubs and trees over shorter-lived, development, and fire suppression crown-sprouting or obligate-seeding have fragmented and degraded shrubs characteristic of the habitat. -

California Flora Nursery Field Inventory for November 7, 2016

California Flora Nursery Field Inventory for November 7, 2016 4 4 inch = $5.00 T " S $9.50 $10.50 $25.00 T = T = 5G = = $35.00 1G perennials & grasses = $8.50/$10.00 P $11.00 P $12.00 $30.00 7G Short Treepot Tall Treepot 5 Gallon 7 Gallon N 4" 4" ferns = $5.50 1G 1G ferns = $10.00 o Lavender labels indicate specialty prices. n 1G vines, shrubs, & trees = $9.50/$11.00 - 10 or more of the same plant 10% off N 20 or more of the same plant 20% off a t i S T v T T 5G e Plant Common Name 4" 1G P P 7G Abies concolor (2 in 2G) white fir 22 Abies grandis grand fir 23 Acer circinatum vine maple 17 15 Acer glabrum Sierra maple 2 Acer macrophyllum bigleaf maple 31 Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' yarrow 13 Adenostema fasciculatum chamise 5 Adiantum capillus-veneris southern maidenhair fern 116 Adiantum X tracyi Tracy's maidenhair fern 36 Aesculus californica California buckeye 39 12 10 Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia mountain alder 2 Amorpha californica napense $15 1 Anemone deltoidea western white anemone 8 Angelica tomentosa foothill angelica 10 8 Arctostaphylos 'Austin Griffiths' manzanita 9 Arctostaphylos canescens canescens 5 Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Carmel Sur' Little Sur manzanita 98 Arctostaphylos 'Emerald Carpet' manzanita 266 Arctostaphylos glandulosa Eastwood manzanita 2 6 Arctostaphylos hookeri 'Monterey Carpet' 2 Arctostaphylos hookeri 'Wayside' 13 Arctostaphylos 'Howard McMinn' manzanita 122 Arctostaphylos 'John Dourley' manzanita 151 4 Arctostaphylos 'Laguna White' manzanita 4 Container Sizes: Outside diameter x Height S T 14" T T 11.5" 1G 9.25" 14" 5G 7G 4" 3.9" 7" P P 3.3" 6" 4" 4" 10" 12" 4 inch 1 Gallon Short Treepot Tall Treepot 5 Gallon 7 Gallon 1 S T N T T 5G N Plant Common Name 4" 1G P P 7G Arctostaphylos 'Lester Rowntree' 14 Arctostaphylos 'Lutsko's Pink' manzanita 8 Arctostaphylos manzanita 50 Arctostaphylos manzanita 'Hood Mountain' 6 Arctostaphylos manzanita 'Sebastopol White' manzanita 2 Arctostaphylos manzanita (St. -

Almeta Barrett

VOLUME 9, NUMBER 3 OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY OCTOBER 2003 Almeta Barrett: Manzanitas – A study in speciation patterns A pioneer woman botanist in Oregon Part II: Summary of the Oregon taxa of Arctostaphylos by Robin Lodewick by Kenton L. Chambers Only a few women, as far as we know, collected new For the Oregon Vascular Plant Checklist, we are plants in the early Pacific Northwest, sending them to the recognizing the following 8 species of manzanitas as Eastern botanical establishment for naming. One of these occurring in the state. This is many fewer than the 57 was Almeta Hodge Barrett, an Oregon pioneer. Almeta was species, with accompanying subspecies, found in the wife of a former Civil War surgeon, Dr. Perry Barrett, California according to the treatment by P. V. Wells in The who began a medical practice in Pennsylvania following the Jepson Manual. Two rare species of northern California war. After losing nearly everything to a fire however, the cited by Wells, A. klamathensis and A. nortensis, are found couple chose to start over in the west. In 1871, with year-old just south of Oregon but have not yet been discovered in daughter Julia, the family traveled to Portland, then up the this state. As mentioned in Part I of this article, most of Columbia to where Hood River joins the mighty River of the taxonomic complexity in Oregon manzanitas is seen in the West. There, in the fertile Hood River Valley, the family Curry, Josephine, and Jackson counties. It is important to established their homestead. observe population variability and to take careful notes on The Barretts built a two-story house and barn and the habit and burl development, when collecting specimens in doctor began to accept patients. -

A Checklist of Vascular Plants Endemic to California

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 3-2020 A Checklist of Vascular Plants Endemic to California James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "A Checklist of Vascular Plants Endemic to California" (2020). Botanical Studies. 42. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/42 This Flora of California is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A LIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS ENDEMIC TO CALIFORNIA Compiled By James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State University Arcata, California 13 February 2020 CONTENTS Willis Jepson (1923-1925) recognized that the assemblage of plants that characterized our flora excludes the desert province of southwest California Introduction. 1 and extends beyond its political boundaries to include An Overview. 2 southwestern Oregon, a small portion of western Endemic Genera . 2 Nevada, and the northern portion of Baja California, Almost Endemic Genera . 3 Mexico. This expanded region became known as the California Floristic Province (CFP). Keep in mind that List of Endemic Plants . 4 not all plants endemic to California lie within the CFP Plants Endemic to a Single County or Island 24 and others that are endemic to the CFP are not County and Channel Island Abbreviations . -

Crstus NURSERY LLC 22711 NW GILLIHAN RD SAUVIE ISLAND, OR 97231 • 503.621.2233 Fun and Games with Sustainability: a Slideshow by Sean Hogan

CrSTUS NURSERY LLC 22711 NW GILLIHAN RD SAUVIE ISLAND, OR 97231 • 503.621.2233 WWW.CISTUS.COM Fun and Games with Sustainability: a slideshow by Sean Hogan 1. It's (not) rocket science 38. Quercus hypoleucoides 2. intimate landscape design 39. Quercus laceyi 3. summer drought an issue ... 40. Quercus phellos 4. native planting? 41. perfect street tree 5. Quercus garryana 42. space saving tree 6. Bioswale / surroundings 43. Huckleberry oak regeneration 7. Bioswale / surroundings 44. Quercus vaccinifolia 8. Bioswale / surroundings 45. blending of native and vernacular 9. Bioswale / surroundings 46. Ceanothus integerrimus 10. Bioswale / surroundings 47. Ceanothus integerrimus 11. Bioswale / surroundings 48. Ceanothus 'Kurt Zadnik' 12. Bioswale / surroundings 49. Ceanothusfoliosus v. vineatus SBH 7667 13. How do we rethink our plant palette? 50. this can even happen to native plants 14. Juncus patens 'Elk Blue' 51. Which way is the wind blowing? 15. Carex (glauca)flacca 52. Arctostaphylos viscida 16. Carex tumulicola 53. Arctostaphylos manzanita 17. Mixed grasses at Suncrest Nursery _ 54. Arctostaphylos manzanita 18. Restio tetraphyllu~, 55. Arctostaphylos manzanita 19. Restio tetraphyllus 56. Arctostaphylos viscida 20. Yucca rostrata 'Sapphire Skies' 57. Arctostaphylos hispidula 21. Camassia leichtlinii var.leichtlinii 58. Arctostaphylos hybrid population near 22. Escholtzia californica and Sisyrinchium Sandy, Oregon 23. Epipactis gigantea 'Serpentine Night' 59. Mixed Arctostaphylos 24. Narthecium californicum 60. Oregon Mountain mix 25. Narthecium californicum 61. wild Oregon wolf 26. Darmera peltata along Illinois River, 62. Arctostaphylos patula & Mt. Hood from Oregon the east 27. Darmera peltata along Illinois River, 63. Arctostaphylos patula with A. columbiana Oregon 64. manzanita with a view 28. Darmera peltata 65.