NH Parker, "Psalm 103: God Is Love; He Will

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7

Chapter 20 4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7 Gaye Strathearn am personally grateful for S. Kent Brown. He was a commit- I tee member for my master’s thesis, in which I examined 4Q521. Since that time he has been a wonderful colleague who has always encouraged me in my academic pursuits. The relationship between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian- ity has fueled the imagination of both scholar and layperson since their discovery in 1947. Were the early Christians aware of the com- munity at Qumran and their texts? Did these groups interact in any way? Was the Qumran community the source for nascent Chris- tianity, as some popular and scholarly sources have intimated,¹ or was it simply a parallel community? One Qumran fragment that 1. For an example from the popular press, see Richard N. Ostling, “Is Jesus in the Dead Sea Scrolls?” Time Magazine, 21 September 1992, 56–57. See also the claim that the scrolls are “the earliest Christian records” in the popular novel by Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 245. For examples from the academic arena, see André Dupont-Sommer, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Preliminary Survey (New York: Mac- millan, 1952), 98–100; Robert Eisenman, James the Just in the Habakkuk Pesher (Leiden: Brill, 1986), 1–20; Barbara E. Thiering, The Gospels and Qumran: A New Hypothesis (Syd- ney: Theological Explorations, 1981), 3–11; Carsten P. Thiede, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Jewish Origins of Christianity (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 152–81; José O’Callaghan, “Papiros neotestamentarios en la cueva 7 de Qumrān?,” Biblica 53/1 (1972): 91–100. -

Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016)

James Block Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016) Contents ARISE OH YAH (Psalm 68) .............................................................................................................................................. 3 AWAKE JERUSALEM (Isaiah 52) ................................................................................................................................... 4 BLESS YAHWEH OH MY SOUL (Psalm 103) ................................................................................................................ 5 CITY OF ELOHIM (Psalm 48) (Capo 1) .......................................................................................................................... 6 DANIEL 9 PRAYER .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 DELIGHT ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 FATHER’S HEART ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 FIRSTBORN ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 GREAT IS YOUR FAITHFULNESS (Psalm 92) ............................................................................................................. 11 HALLELUYAH -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

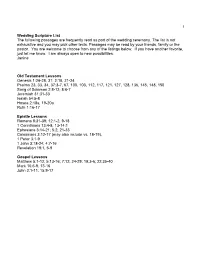

1 Wedding Scripture List the Following Passages Are Frequently Read As

1 Wedding Scripture List The following passages are frequently read as part of the wedding ceremony. The list is not exhaustive and you may pick other texts. Passages may be read by your friends, family or the pastor. You are welcome to choose from any of the listings below. If you have another favorite, just let me know. I am always open to new possibilities. Janine Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31; 2:18, 21-24 Psalms 23, 33, 34, 37:3-7, 67, 100, 103, 112, 117, 121, 127, 128, 136, 145, 148, 150 Song of Solomon 2:8-13; 8:6-7 Jeremiah 31:31-33 Isaiah 54:5-8 Hosea 2:18a, 19-20a Ruth 1:16-17 Epistle Lessons Romans 8:31-39; 12:1-2, 9-18 1 Corinthians 13:4-8, 13-14:1 Ephesians 3:14-21; 5:2, 21-33 Colossians 3:12-17 (may also include vs. 18-19). 1 Peter 3:1-9 1 John 3:18-24; 4:7-16 Revelation 19:1, 5-9 Gospel Lessons Matthew 5:1-12; 5:13-16; 7:12, 24-29; 19:3-6; 22:35-40 Mark 10:6-9, 13-16 John 2:1-11; 15:9-17 2 Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31 Then God said, "Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth." So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. -

Psalms the Human Condition Life in the Ancient World Was Nasty, Brutish

Psalms The Human Condition Life in the ancient world was nasty, brutish, and short, and ancient Israel was no exception. The Psalms, more than any other book in the Bible, provide a window to the experiences of ordinary people. Out of the Depths Many of the psalms of complaint are cries of despair: “out of the depths I cry to you O Lord” (Psalm 130:1). Life is lived in the shadow of death, and of the netherworld Sheol: For my soul is full of troubles, and my life draws near to Sheol. I am counted among those who go down to the Pit . like those whom you remember no more, for they are cut off from your hand. You have put me in the depths of the Pit, in the regions dark and deep. (Psalm 88:3,5b-6) Human life was not entirely extinguished at death, but afterlife in Sheol was nothing to look forward to. Sheol is imagined as a dark damp basement, a pit from which there is no escape. There is no enjoyment in Sheol. The dead cannot even praise the Lord (Psalm 115:17). Indeed, in Sheol there is not even remembrance of God (Psalm 6:5). Consequently, life is lived in fear of going down into Sheol: The waters have come up to my neck. I sink in deep mire where there is no foothold . Do not let the flood sweep over me or the deep swallow me up or the Pit close its mouth over me (Psalm 69:1-2, 15). A Temporary Reprieve When the Psalmist prays to be delivered from Sheol, the request is for a temporary reprieve or for a postponed sentence. -

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: the Master Musician’S Melodies

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Sunday School Placerita Baptist Church 2007 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Psalm 103 — David’s Doxology: The Sum of the Psalter 1.0 Introducing Psalm 103 y Book 4 of the Psalter concludes with four psalms calling God’s people to bless, thank, and praise Him. Note the way that these four psalms begin and end: Psalm 103 104 105 106 Beginnin Bless the LORD, O Bless the LORD, O Oh give thanks to Praise the LORD! Oh g my soul, And all that my soul! O LORD my the LORD, call upon give thanks to the is within me, bless God, You are very His name; Make LORD, for He is good; His holy name. (v. 1) great; You are clothed known His deeds For His with splendor and among the peoples. lovingkindness is majesty, (v. 1) (v. 1) everlasting. (v. 1) Ending Bless the LORD, all Let sinners be So that they might Blessed be the LORD, you works of His, In consumed from the keep His statutes And the God of Israel, all places of His earth And let the observe His laws, From everlasting even dominion; Bless the wicked be no more. Praise the LORD! to everlasting. And let LORD, O my soul! Bless the LORD, O (v. 45) all the people say, (v. 22) my soul. Praise the “Amen.” Praise the LORD! (v. 35) LORD! (v. 48) y Book 4 contains only two psalms attributed to David (Psalms 101 and 103). -

Exercises the Psalms: Prayer Book for the People of God Ada Bible Church, October 31 – December 19, 2019

Revised: October 17, 2019 EXERCISES THE PSALMS: PRAYER BOOK FOR THE PEOPLE OF GOD ADA BIBLE CHURCH, OCTOBER 31 – DECEMBER 19, 2019 A. QUIZZES ON N. T. WRIGHT’S THE CASE FOR THE PSALMS Purpose: To ensure that students are reading the textbook with sufficient comprehension to integrate the readings into classroom learning. Instructions: We will take 10 minutes for each quiz. Each quiz will have about 7 questions. Format: We will first answer the quiz questions individually and then review the correct answers as a group. The class will receive points for answering questions with at least 75% accuracy. QUIZ 1: QUESTIONS 1‒7 CHAPTER 1: “INTRODUCTION” (PP. 1–12): 1. In his opening plea that we read the Psalms, Wright cites each of the following reasons EXCEPT: a. The Psalms are among the oldest poems in the world b. The Psalms translate into modern languages with surprising power and clarity c. The Psalms served as the hymnbook for ancient Judaism and Christianity d. The Psalms are treasured by all world religions today 2. With which of the following phrases does N. T. Wright characterize contemporary worship songs that are not rooted in the Psalms? a. They are a “great impoverishment” b. They are “more accessible to the modern ear” c. They can “better reflect the cultural needs of the day” d. They are “theologically hazardous” 3. N. T. Wright sees the regular praying and singing of the Psalms as which of the following? a. Monotonous b. Exhilarating c. Transformative d. Sublime Page 1 4. N. T. Wright explains what a “worldview” is with which of the following metaphors? a. -

Small Group Questions “Doxology” Psalm 103

Option 2 - We realize you may not be able to discuss In Psalm 103:10 we are told that God does not give us what all the questions. Pick the ones you prefer. we deserve. On paper or just in your memory, think of some low points in your life where you have rebelled and committed Small Group Questions “Doxology” a sin. Don’t stay there very long. Next, take that list and read Psalm 103 out loud Psalm 103:9-12 and let the word pictures of these This Week’s Announcements: verses be done to your mistakes. Please offer your feedback: If you will complete the survey found at Memory Verse: http://tinyurl.com/olbj8pl you will be placed in a drawing for a gift certificate - Psalm 103:2 - Bless the LORD, O my soul, and forget not all Dinner for two at one of the following restaurants: Bardeney's, Mongolian BBQ, his benefits. Idaho Pizza, or Dickey's BBQ. ECC Celebrates 20 Years! We will celebrate 20 years as a church in Next Steps: September, and are planning several special events during the month, including I will join all creation in declaring the greatness of God. an open house on September 19, from 4 to 6:45 pm. If you are interested in helping with any of the events, please sign up at the Welcome Center. Also, if you I will seek to imitate the compassion of God as a have any memorabilia or photos of the early days of the church that you’d like to parent or grandparent (Ps 103:13, 17-18). -

Psalms-Quiet-Times.Pdf

Psalms 90-106 Over the next 20 days, let us rest in the book of Psalms. The collection of Book 4 (Psalms 90-106) follows a myriad of exilic and post-exilic laments. In response to the devastation of Jerusalem, Psalm 90 begins recalling that God has been their “dwelling place through all generations.” At the centre of these Psalms is a celebration of God’s reign as King, ending with two Psalms retelling Israel’s history. These quiet times use a fairly standard method of Bible reading with a series of questions to have in mind as you read and reflect. The aim of these questions is to keep your mind and heart engaged throughout, rather than just going through the motions. The standard questions we will ask are: What stands out? What questions do you have? How does the reading point to Jesus? What could you pray? Who could you encourage? You may come to the end of a reading and think, ‘wow, I cannot figure out how that points to Jesus and I have no idea how the passage would help me encourage anyone’. That’s fine! The standard questions we will use may not fit every passage. However, they are important to ask none the less, as they keep us open to the Spirit’s leading as we read. I also like to recommend the Australian Christian band “Sons of Korah” as a wonderful companion to this series. They have composed beautiful versions of Psalm 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 99, 100, 103. You can listen to their music on Spotify, Itunes & Youtube. -

“Praise.” Psalms 113-118 Are Hymns of Praise to God

WHO IS LIKE THE LORD OUR GOD? Psalm 113 Psalm 113 is the first of a series of psalms called the EGYPTIAN HALLEL. Hallel means, “praise.” Psalms 113-118 are hymns of praise to God. It is called the EGYPTIAN HALLEL because of the reference to the Exodus in Psalm 114:1. And this collection of psalms was sung during Jewish holy days, especially the Passover. Psalms 113 and 114 were sung before the Passover meal. Psalms 115 through 118 were sung after the meal. Jesus and his disciples most likely sung these six psalms at the Last Supper the night he was betrayed. The EGYPTIAN HALLEL begins with Psalm 113. We do not know the author, background, or occasion of this psalm. But the message is unmistakably clear. God is worthy to be praised. So clear is this message that a theology of praise can be developed from this psalm. First of all, this psalm teaches that praise is essential to worship. Worship is more than praise. But is it worship without praise? A worship service may consist of singing, scripture reading, prayer, preaching, giving, baptism, and the Lord’s Table. But the fact that you are in a worship service does not make you a worshiper. A worship service without true praise is a sit-in. It is a protest disguised as worship. True worship involves passionate praise. This psalm also teaches that praise is God-centered. It is not about us. It is about God. God is the target-audience in Christian worship. He is the subject and object of our praise. -

The Praise of God and His Name As the Core of the Second Temple Liturgy

ZAW 2015; 127(3): 475–488 Mika S. Pajunen* The Praise of God and His Name as the Core of the Second Temple Liturgy DOI 10.1515/zaw-2015-0026 Praise of God, alongside the reading of the Law and the sacrificial cult, has always been understood by scholars as a primary element of the liturgical life of the Second Temple period.¹ Form critics working in the 20th century, like Hermann Gunkel, Sigmund Mowinckel and in the case of praises particularly Claus Wester- mann, situated the praises of God in the liturgical practice of the Second Temple period most of all by analyzing the Psalms now in the MT Psalter.² Hence, they conceived the liturgical core of the Second Temple to revolve around praise and lament because those two form-critically defined categories of Psalms made up about two thirds of the Psalms in the Psalter.³ However, it has also been well rec- ognized that these categories of psalms, and especially lament, cannot form a basis for understanding the liturgy of the late Second Temple period at least from 1 A wide definition of liturgy that tries to avoid preconceptions of what a liturgy could contain is preferred in this study. A similar view has been posited, for example, by Stefan C. Reif, Judaism and Hebrew Prayer: New Perspectives on Jewish Liturgical History (Cambridge: Cambridge Uni- versity Press, 1993), 71 f., who argues that liturgy in Second Temple Judaism could contain, for instance, acts of mystical piety, temple offering, study, benediction or praise, etc. It is acknowl- edged that when discussing such a long time period there is bound to have been change and variance in the liturgical practices that have also left traces in the textual evidence. -

Scottish Psalter and Paraphrases by Anonymous About Scottish Psalter and Paraphrases

Scottish Psalter and Paraphrases by Anonymous About Scottish Psalter and Paraphrases Title: Scottish Psalter and Paraphrases URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/anonymous/scotpsalter.html Author(s): Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: This contains the Scottish Psalter and Scripture Paraphrases, the primary hymnal of the Church of Scotland up through the 19th century. First Published: 1650 (Psalter); 1781 (Paraphrases) Publication History: These texts have remained in print and in use since their first publication. Print Basis: The Psalms and Church Hymnary, 3rd edition: London, Oxford University Press, 1973. Source: Online Bible Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2001-09 Status: Profitable future work may include: ·Collation against a printed source. Editorial Comments: Orthography was edited to facilitate automated use: ·Added numeric meter notation ("8,8,8,8,8,8", etc.) ·ThML markup (assuming HTML semantics of whitespace) ·Page numbers from "The Psalms and Church Hymnary" Contributor(s): H.Sikkema (Transcriber) Stephen Hutcheson (Formatter) Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Psalms of David in Metre. p. 1 Psalm 1: That man hath perfect blessedness. p. 1 Psalm 2: Why rage the heathen? and vain things. p. 1 Psalm 3: O Lord, how are my foes increas©d?. p. 3 Psalm 4: Give ear unto me when I call. p. 3 Psalm 5: Give ear unto my words, O Lord. p. 4 Psalm 6, L.M.: Lord, in thy wrath rebuke me not. p. 5 Psalm 6, C.M.: In thy great indignation. p. 6 Psalm 7: O Lord my God, in thee do I. p. 7 Psalm 8: How excellent in all the earth.