FOUR DECADES of DEVELOPMENT ( Review Conference)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

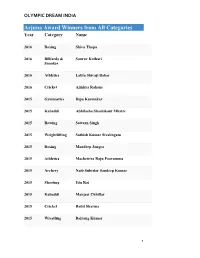

Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name

OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name 2016 Boxing Shiva Thapa 2016 Billiards & Sourav Kothari Snooker 2016 Athletics Lalita Shivaji Babar 2016 Cricket Ajinkya Rahane 2015 Gymnastics Dipa Karmakar 2015 Kabaddi Abhilasha Shashikant Mhatre 2015 Rowing Sawarn Singh 2015 Weightlifting Sathish Kumar Sivalingam 2015 Boxing Mandeep Jangra 2015 Athletics Machettira Raju Poovamma 2015 Archery Naib Subedar Sandeep Kumar 2015 Shooting Jitu Rai 2015 Kabaddi Manjeet Chhillar 2015 Cricket Rohit Sharma 2015 Wrestling Bajrang Kumar 1 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2015 Wrestling Babita Kumari 2015 Wushu Yumnam Sanathoi Devi 2015 Swimming Sharath M. Gayakwad (Paralympic Swimming) 2015 RollerSkating Anup Kumar Yama 2015 Badminton Kidambi Srikanth Nammalwar 2015 Hockey Parattu Raveendran Sreejesh 2014 Weightlifting Renubala Chanu 2014 Archery Abhishek Verma 2014 Athletics Tintu Luka 2014 Cricket Ravichandran Ashwin 2014 Kabaddi Mamta Pujari 2014 Shooting Heena Sidhu 2014 Rowing Saji Thomas 2014 Wrestling Sunil Kumar Rana 2014 Volleyball Tom Joseph 2014 Squash Anaka Alankamony 2014 Basketball Geetu Anna Jose 2 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2014 Badminton Valiyaveetil Diju 2013 Hockey Saba Anjum 2013 Golf Gaganjeet Bhullar 2013 Athletics Ranjith Maheshwari (Athlete) 2013 Cricket Virat Kohli 2013 Archery Chekrovolu Swuro 2013 Badminton Pusarla Venkata Sindhu 2013 Billiards & Rupesh Shah Snooker 2013 Boxing Kavita Chahal 2013 Chess Abhijeet Gupta 2013 Shooting Rajkumari Rathore 2013 Squash Joshna Chinappa 2013 Wrestling Neha Rathi 2013 Wrestling Dharmender Dalal 2013 Athletics Amit Kumar Saroha 2012 Wrestling Narsingh Yadav 2012 Cricket Yuvraj Singh 3 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2012 Swimming Sandeep Sejwal 2012 Billiards & Aditya S. Mehta Snooker 2012 Judo Yashpal Solanki 2012 Boxing Vikas Krishan 2012 Badminton Ashwini Ponnappa 2012 Polo Samir Suhag 2012 Badminton Parupalli Kashyap 2012 Hockey Sardar Singh 2012 Kabaddi Anup Kumar 2012 Wrestling Rajinder Kumar 2012 Wrestling Geeta Phogat 2012 Wushu M. -

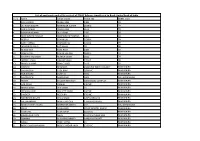

List of Candidates Called for Written Examination CORRIGENDUM

CORRIGENDUM The written examination for the post of Senior Assistant (Nursing) in Northern Region will be held on 23.09.2012 (Sunday) instead of 09.09.2012 (Sunday) as follows:- Centre : Shyam Lal College, G.T. Road, Opposite Welcome Metro Station, Shahdara, Delhi-110032. Date of Examination : 23.09.2012 (Sunday) Timing : 1400 hrs to 1600 hrs Reporting Time : 1330 hrs IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS: 1. The undermentioned candidates are called for the written examination for the post of Sr. Asstt. (Nursing). 2. The candidate should ensure that he/she fulfill the eligibility criteria as mentioned in the advertisement for the said post before appearing in the written examination. 3. The appearance in the written examination is provisional and if candidate is found to be ineligible at any stage as per criteria mentioned in the advertisement, his candidature will be cancelled without any notice. 4. If, any candidate does not receive the Call Letter which are already dispatched, he/she may contact the AAI representative at Examination Centre with two recent passport size photographs and photo identity proof in original for issuance of duplicate Call Letter at the Centre. Such candidates should contact the AAI representative well in advance i.e. before 1330 hrs at Examination Centre. List of Candidates called for Written Examination SrlNo Regn Name Father Name Catgy Centre RollNo 1 120029 A. DEIVANAI V. ANNAMALAI OBC 9 90900824 2 120030 A. SHANMUGAVALLI V. ANNAMALAI OBC 9 90900127 3 120569 A.MURUGAN C.ARUMUGAM OBC 9 90900099 4 120312 ABDUL HAMEED KHAN DIN MOHAMMAD OBC 9 90900273 5 120066 ABDUL RAFEEQ KHAN ABDUL AZIZ KHAN GEN 9 90900629 6 120630 ABDUL SATHAR K.T. -

List of Applicants Under Clss Vertical of PMAY Scheme Transferred to Bank

List of applicants under Clss vertical of PMAY Scheme transferred to Bank-United bank of India Sr.no Name Father_Name House_No Street_Slum 1 SHIV KUMAR MUNSI RAM 1381 39 2 JATINDER KUMAR MOHINDER KUMAR 2538/G 39 3 SUNIL KUMAR PHULA RAM 2612 39 4 ASHWANI KUMAR DULO RAM 2585 39 5 MOHAMMAD YOUSUF MOHAMMAD YOUNUS B-14 39 6 NEERAJ SOHAN LAL 3138/A 39 7 AARTI VERMA BRAHAM PAL 1350/A 39 8 JASWINDER KAUR AJIT SINGH 20 39 9 MINDA DEVI KAKA RAM 2483 39 10 KESHAV GILL SOHAN LAL GILL 2602/A 39 11 KRISHAN PAL SINGH MUNNA SINGH 2582 39 12 JARNAIL SINGH UJAGAR SINGH 1709/1 39 13 MANOJ KUMAR GIAN CHAND 3119 39 14 ROSHAN MASROOR 2344 NEW INDIRA COLONY MANIMAJRA 15 SAVITRI DEVI TUDE RAM 2036 NIC MANIMAJRA 16 ROBIN GARG GORE LAL 1890 MANIMAJRA 17 SAVITRI DEVI RAM NIHAR 1809 NIC, MANIMAJRA 18 MEERA BALGOVIND SINGH 2800 MOULI COMPLEX MANIMAJRA 19 HAR PYARI LAKHAN 240 NIC MANIMAJRA 20 MANJIT KAUR DEV SINGH 73 MANIMAJRA 21 KRISHNA KAUR MALKEET SINGH 260 NIC MANIMAJRA 22 SANDEEP MEGH RAJ 670 NIC MANIMAJRA 23 NOORESHA BEGAM INSUL NADAF 1237 MORIGATE MANIMAJRA 24 FAEEM AHMAD MOND SADIQUE 1786/4 MORIGATE MANIMAJRA 25 MOND YUSUF JULAHA MOHBOOB ANMED 452 NIC, MANIMAJRA 26 VIKAS RAJ KUMAR 325/D SHASTRI NAGAR MANIMAJRA 27 RAM VATI RAM AVTAR 2151 NIC MANIMAJRA 28 ZAHIDA KHATOON NAFIS 1119/2 GOVINDPURA MANIMAJRA 29 SHAHNAJ MUKHIYAR ANMED 1048/1 MORIGATE MANIMAJRA 30 ANJALI PRABHUDYAL 46 MANIMAJRA 31 MOND SHADMAN KHAN MOND SARDAR KHAN 1242 NIC MANIMAJRA 32 PANKAJ NEGI PARBAL SINGH 1299/1 NAGLA BASTI MANIMAJRA 33 RAJ KUMARI MUNSHI RAM 2238/34 PIPLIWALA TOWN, MANIMAJRA -

Athletics, Badminton, Gymnastics, Judo, Swimming, Table Tennis, and Wrestling

INDIVIDUAL GAMES 4 Games and sports are important parts of our lives. They are essential to enjoy overall health and well-being. Sports and games offer numerous advantages and are thus highly recommended for everyone irrespective of their age. Sports with individualistic approach characterised with graceful skills of players are individual sports. Do you like the idea of playing an individual sport and be responsible for your win or loss, success or failure? There are various sports that come under this category. This chapter will help you to enhance your knowledge about Athletics, Badminton, Gymnastics, Judo, Swimming, Table Tennis, and Wrestling. ATHLETICS Running, jumping and throwing are natural and universal forms of human physical expression. Track and field events are the improved versions of all these. These are among the oldest of all sporting competitions. Athletics consist of track and field events. In the track events, competitions of races of different distances are conducted. The different track and field events have their roots in ancient human history. History Ancient Olympic Games are the first recorded examples of organised track and field events. In 776 B.C., in Olympia, Greece, only one event was contested which was known as the stadion footrace. The scope of the games expanded in later years. Further it included running competitions, but the introduction of the Ancient Olympic pentathlon marked a step towards track and field as it is recognised today. There were five events in pentathlon namely—discus throw, long jump, javelin throw, the stadion foot race, and wrestling. 2021-22 Chap-4.indd 49 31-07-2020 15:26:11 50 Health and Physical Education - XI Track and field events were also present at the Pan- Activity 4.1 Athletics at the 1960 Summer Hellenic Games in Greece around 200 B.C. -

Multipolis Mumbai

A panel discussion on the synergies between technology and art this International Museum Day For Immediate Release Technology and creativity are key in uniting communites and driving innovation. Throughout history, technology has provided artists with new tools for expression. Today, these two seemingly distinct disciplines are interlinked more than ever, with technology being a fundamental force in the development and evolution of art. Technology can help turn our cities into safer, better-connected, resource sustainable and more interactive hubs. As part of this, access to art and cultural institutions plays a pivotal role in the overall liveability of a city. With recent innovations, creative institutions and individuals have begun to foray into the world of technology. NGMA Mumbai, Ministry of Culture, Government of India in association with Avid Learning present Multipolis Mumbai: Art and Technology in the City, a panel discussion on the collaborative synergies between art and technology and how artists and cultural institutions and harnessing the power of tech. The description of the discussion is as below: Head of Business Development - India & South East Asia at Google Shishir Jayant, Professor, Industrial Design Centre, IIT Bombay Sumant Rao, Artist and Founder of the MISSING Campaign, Leena Kejriwal, Director at Nehru Science Centre, Mumbai and National Gallery of Modern Art Mumbai Shivaprasad Khened will be in conversation with Special Correspondent (Arts and Features) at Mumbai Mirror Reema Gehi. They will discuss how technology is making a sizeable and positive impact in the art world and how artists, museums and institutions are leveraging technological advancements to revolutionize how art is produced and reproduced, archived and preserved, consumed and made more widely accessible than ever before. -

1000+ Question Series PDF -Jklatestinfo

JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q1) The kashmir Valley was originally a huge lake called ? a) Manesar b) Neelam c) Satisar d) Both ‘b’ & ‘c’ Q2) Kalhana , a famous historian wrote ? a) Nilmatpurana b) Rajtarangini c) Both d) None of these Q3) The First king mentioned by Kalhana is ? a) Gonanda I b) Durlabha Vardhana c) Ashoka d) Jalodbhava Q4) The outer plains doesn’t cover which of the following ? a) RS Pura b) Kathua c) Akhnoor d) Udhampur Q5) When J&K became Union Territory ? a) August 5, 2019 b) October 31, 2019 c) September 5, 2019 d) October 1 , 2019 JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q6) Which among the following is the welcome dance for spring season ? a) Bhand Pathar b) Dhumal c) Kud d) Rouf Q7) Total number of districts in J&K ? a) 22 b) 21 c) 20 d) 18 Q8) On which hill the Vaishno Devi Mandir is located ? a) Katra b) Trikuta c) Udhampur d) Aru Q9) The SI unit of charge is ? a) Ampere b) Coulomb c) Kelvin d) Watt Q10) The filament of light bulb is made up of ? a) Platinum b) Antimony c) Tungsten d) Tantalum JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q11) Battle of Plassey was fought in ? a) 1757 b) 1857 c) 1657 d) 1800 Q12) Indian National Congress was formed by ? a) WC Bannerji b) George Yuli c) Dada Bhai Naroji d) A.O HUme Q13) The Tropic of cancer doesn’t pass through ? a) MP b) Odisha c) West Bengal d) Rajasthan Q14) Which of the following is Trans-Himalyan River ? a) Ganga b) Ravi c) Yamuna d) Indus Q15) Rovers cup is related to ? a) Hockey b) Cricket c) Football d) Cricket JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ -

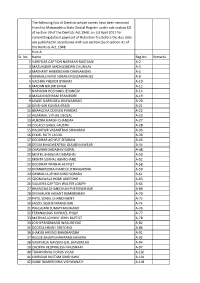

DEFAULTER PART-A.Xlsx

The following lists of Dentists whose names have been removed from the Maharashtra State Dental Register under sub-section (2) of section 39 of the Dentists Act,1948, on 1st April 2017 for committing default payment of Retention fee before the due date are published in accordance with sub section (5) of section 41 of the Dentists Act, 1948. Part-A Sr. No. Name Reg.No. Remarks 1 VARIFDAR CAPTION NARIMAN RUSTAMJI A-2 2 MAZUMDAR MADHUSNDAN CHUNILAL A-3 3 MAEHANT HARIKRISHAN DHANAMDAS A-5 4 GINWALS MINO SORABJI NUSSAWANJEE A-9 5 VACHHA PHEROX BYRAMJI A-10 6 MADAN BALBIR SINGH A-12 7 NARIMAN HOSHANG JEHANGIV A-14 8 MASANI BEHRAM FRAMRORE A-19 9 JAWLE NARENDEA BHAWANRAO A-20 10 DINSHAW KAVINA ERAEH A-21 11 BHARUCHA COOVER PHIRORE A-22 12 AGARWAL VITHAL DEOLAL A-23 13 AURORA HARISH CHANDAR A-27 14 COLACO ISABEL FAUSTIN A-28 15 HALDIPWR VASANTRAO SHAMRAO A-33 16 EEKIEL RUTH JACOB A-39 17 DEODHAR ACHYUT SITARAM A-43 18 DESIAI BHAGWENTRAI GULABSHAWEAR A-44 19 CHAVHAN SADASHIV GOPAL A-48 20 MISTRI JEHANGIR DADABHAI A-50 21 MEHTA SUKHAL ABHECHAND A-52 22 DEODHAR PRABHA ACHYUT A-58 23 DHANBHOORA MANECK JEHANGIRSHA A-59 24 GINWALLA JEHMI MINO SORABJI A-61 25 SOONAWALA HOMI ARDESHIR A-63 26 SIGUEIRA CAPTION WALTER JOSEPH A-65 27 BHANICHA DHANJISHAH PHERIZWSHAW A-66 28 DESHMUKH VASANT RAMKRISHAN A-70 29 PATIL SONAL CHANDHAKNT A-72 30 JAGOS JASSI BYARANSHAW A-74 31 PAHLAJANI SUMATI MUKHAND A-76 32 FERANANDAS RUPHAEL PHILIP A-77 33 MATHIAS JOHNNY JOHN BAPTIST A-78 34 JOSHI PANDMANG WASUDEVAO A-82 35 DCOSTA HENNY SERTORIO A-86 36 JHAKUR ARVIND BHAKHANDRA -

M.B.A (Health Care and Hospital Management) Entrance Examination - 201{

H-3F HALL TICKET NO: M.B.A (Health Care and Hospital Management) Entrance Examination - 201{ February, 2015 Max. Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS Write you Hall 7'icket Nu.ntber in the OMR Answer sheet gi'tten to you. AIso write the Halt Ticket Number in the space provided above. question The paper booklet consists of 100 Questions. Each question carries one (l) mark. There is a negative marking. Each wrong answer carries - 0.33 marlrs. Ansu'ers are to be markezd on the OMR onswer sheet following the instructions provided thereupon. Hand over the OMR ansu)er sheet at the end of the examination to the Invigilator. No additional sheet (s) will be provided, rough v,ork can be done in the question paper itself/space provided at the end of the booklet. Calculator, mobile phone,s and electronic gadgets are not allowed. H -3tr journey at the speed 1. A man completed a journey in 10 hours. He travels first half distance of the joumey of 60 kmph and second half at the rate of 40 kmph' Find the total in km' A)240 B) 480 c) 600 D)720 price? Z. A vendor bought a product at Rs. 500 after availing 20% discount. What was the marked A) Rs. 62s B) Rs.550 c) tu. 600 D) Rs.750 5 the area of the rectangle is 3 . The ratio between the length and the breadth of a rectangle is : L If 720 sq. cm, what is the perimeter of the rectangle (in cm)? A)72 B) 108 c) 144 D) i80 4. -

461 Indians on the Bolivian Side Pomaratu. They Climbed to Its Top

CLIMBS AND EXPEDITIONS 461 Indians on the Bolivian side Pomaratu. They climbed to its top on October 12, placing only one camp at 17,000 feet. As far as is known, Parinacota (20,768 feet) had been climbed twice before. Pomarata, which seems to be the correct name (20,473 feet) was claimed as a first ascent by Bolivians in 1946, but there is no certainty of this climb. The top of Pomarata is heavily glaciated. OSCAR GONZALEZ FBRRAN, Chb Andho de Chile Argentina El Tore. A most extraordinary find was made by two climbers, Erich Groch and Antonio Beorchia, when on January 28 they made what they had assumed would be the first ascent of El Toro (20,952 feet), in the Province of San Juan. On the summit they found what appeared to be a human head lying on the surface. When they tried to lift it, they dis- covered it was still attached to a mummified body. They returned with others to retrieve the body, which had been there at least 450 years, a sacrificial victim with a wound at the back of the head. He had been a young man of between 15 to 20 years. He was in a sitting position with his hands crossed below his knees, dressed in gray trousers with red trimmings, a red wool cap and a poncho. Under the body a rat was found, also mummified. Central Argentina. The highest peak in the Mo?zgotes group, a snow and ice peak about 19,350 feet high, was climbed in January by R. -

History of Science Museums and Planetariums in India*

Indian Journal of History of Science, 52.3 (2017) 357-368 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2017/v52i3/49167 Project Report History of Science Museums and Planetariums in India* Jayanta Sthanapati** 1. INTRODUCTION III. Planetariums The current study has been envisaged to IV. Natural History Museums present a comprehensive history of the V. Mobile Science Exhibition development of Indian Science Museums and Planetariums, and study their exhibits and VI. Interview of Pioneers of Science Museums and activities. Based on available documents, their Planetariums impact in enhancing public understanding of Details of the findings are presented in the science and technology has also been attempted. following sections: Two major accounts on science museum (or science centre) movement in India, written by 2. SCIENCE MUSEUMS, SCIENCE CENTRES Dr Saroj Ghose, former Director General of AND SCIENCE CITIES NCSM (1986-1997) and Shri Ingit K Mukhopadhyay, former DG NCSM (1997-2009) In the early years of 1950s, Pandit and on Indian planetariums by Shri Piyush Pandey, Jawaharlal Nehru, First Prime Minister of India, former Director of Nehru Planetarium, Mumbai Shri G D Birla, a renowned industrialist, Prof K S (2003-2011) though not very comprehensive in Krishnan, a world renowned physicist and Dr B historical studies of science museums and C Roy, a renowned physician and the then Chief planetariums in India has helped us a lot to prepare Minister of West Bengal took considerable interest our document. However, there was not a single in establishment of Science Museums in the account available on the history of natural history country. With their support and under the museums in India. -

General Knowledge Objective Quiz

Brilliant Public School , Sitamarhi General Knowledge Objective Quiz Session : 2012-13 Rajopatti,Dumra Road,Sitamarhi(Bihar),Pin-843301 Ph.06226-252314,Mobile:9431636758 BRILLIANT PUBLIC SCHOOL,SITAMARHI General Knowledge Objective Quiz SESSION:2012-13 Current Affairs Physics History Art and Culture Science and Technology Chemistry Indian Constitution Agriculture Games and Sports Biology Geography Marketing Aptitude Computer Commerce and Industries Political Science Miscellaneous Current Affairs Q. Out of the following artists, who has written the book "The Science of Bharat Natyam"? 1 Geeta Chandran 2 Raja Reddy 3 Saroja Vaidyanathan 4 Yamini Krishnamurthy Q. Cricket team of which of the following countries has not got the status of "Test" 1 Kenya 2 England 3 Bangladesh 4 Zimbabwe Q. The first Secretary General of the United Nation was 1 Dag Hammarskjoeld 2 U. Thant 3 Dr. Kurt Waldheim 4 Trygve Lie Q. Who has written "Two Lives"? 1 Kiran Desai 2 Khushwant Singh 3 Vikram Seth 4 Amitabh Gosh Q. The Headquarters of World Bank is situated at 1 New York 2 Manila 3 Washington D. C. 4 Geneva Q. Green Revolution in India is also known as 1 Seed, Fertiliser and irrigation revolution 2 Agricultural Revolution 3 Food Security Revolution 4 Multi Crop Revolution Q. The announcement by the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited Chairmen that India is ready to sell Pressurised 1 54th Conference 2 53rd Conference 3 51st Conference 4 50th Conference Q. A pension scheme for workers in the unorganized sector, launched recently by the Union Finance Ministry, has been named 1 Adhaar 2 Avalamb 3 Swavalamban 4 Prayas Q. -

Model Question Paper (Along with Answers) on General Awareness (10 Question Set -500 Questions)

Model Question Paper (Along with answers) on General Awareness (10 Question Set -500 Questions) Model Question Paper, Question Set - 1 (1 - 50), General Awareness Q.1. The Vernacular Press Act was passed by: A. Lord Curzon B. Lord Wellesley C. Lord Lytton D. Lord Hardinge Answer: C Q.2. The leader of Young Bengal Movement was: A. Dwarkanath Tagore B. Chandrashekhar Deb C. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar D. Henry Vivian Derozio Answer: D Q.3. Swaraj as a national demand was first made by: A. Chittaranjan Das B. Jawaharlal Nehru C. Dadabhai Naoroji D. Bal Gangadhar Tilak Answer: D Q.4. Muslim League first demanded partition of India in: A. 1906 B. 1916 C. 1940 D. 1946 Answer: C Q.5. The English Weekly edited by Mahatma Gandhi was: A. Kesari B. Comrade C. Bombay Chronicle D. Young India Answer: D Q.6. The Doctrine of Lapse was introduced by: A. Lord Wellesley B. Warren Hastings C. Lord Canning D. Lord Dalhousie Answer: D Q.7. The founder of Boy Scouts and Civil Guides Movement in India was: A. Charles Andrews B. Baden Powell C. Richard Temple D. Robert Montgomery Answer: B Q.8. From where did Mahatma Gandhi start his historic Dandi March? A. Champaran B. Sabarmati Ashram C. Chauri Chaura D. Dandi Answer: B Q.9. Who was the first Indian to pass the Indian Civil Service? A. Dadabhai Naoroji B. Surendranath Banerjee C. Bal Gangadhar Tilak D. D. N Wacha Answer: B Q.10. Who among the following could not be captured by the British in 1857? A.